Trogoniformes: Trogonidae

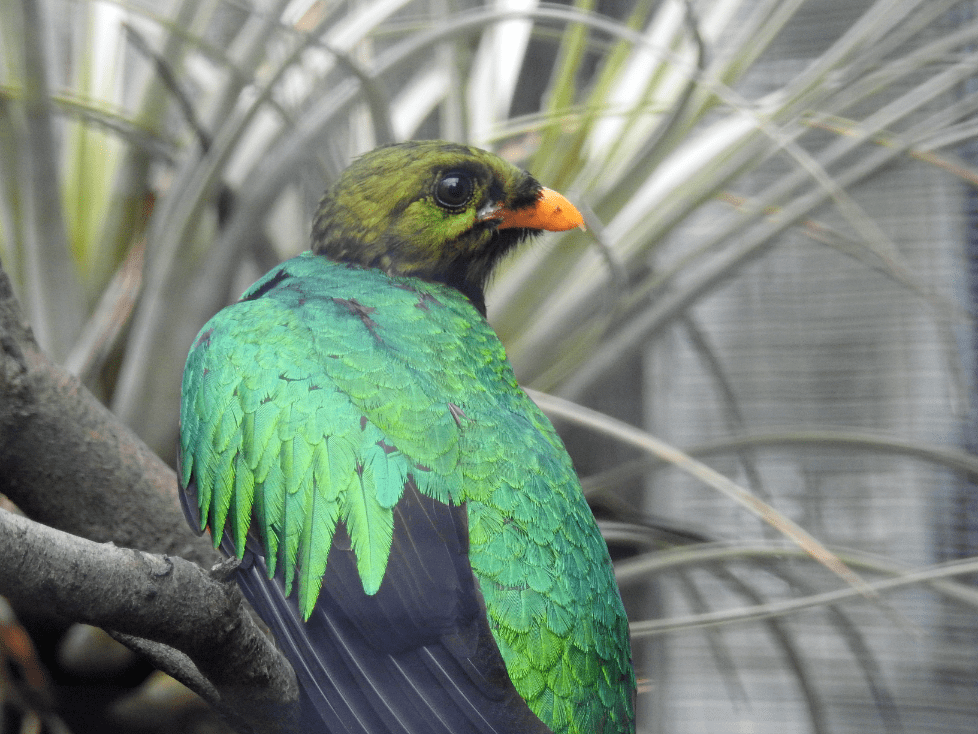

Figure 01a. Not a lot of action shots with trogons; they can sit motionless for long periods of time. If this male Green-backed Trogon were sitting in a dense forest, instead of in the Hummingbird Habitat of the San Diego Zoo, he would be hard to spot.

The avian order Trogoniformes includes just one bird family: Trogonidae. The Trogonidae family contains 7 genera, divided among 47 species. The quetzals include 2 genera, across 6 species. Trogons include 5 genera, across 41 species; the New World genus Trogon includes 24 of the 47 species in this family. The word trogon comes from Greek, trogein, meaning “to gnaw” (or perhaps “to nibble”), which these birds will do, both when eating and when excavating decayed trees to carve out nest cavities for their young.

To see exquisite illustrations of numerous Trogonidae species, please visit https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/215892#page/27/mode/1up , archival images from A Monograph of the Trogonidae or Family of Trogons, written by John Gould and beautifully illustrated by Elizabeth Gould, originally published in 1835. The Goulds ably identified myriad birds around the world, a challenging feat at that time.

Figure 01b. Astonishingly, Resplendent Quetzal males have tail streamers of 12–39.6″ / 31–100.5 cm, with a median length of 30″ / 75 cm!!! per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Resplendent_quetzal ; those are definitely the longest tails among trogons. This image was created by Sidney Bragg, on 31 January 2019, originally posted to https://www.flickr.com/photos/debandsid/32208944717/. It’s licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. It can be shared, but you must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

Trogonidae are medium-sized, stocky birds (9–16″ / 23–40 cm long, head to tail; weighing 1.2–3.9 oz. / 34–210 g). (Their size range has been compared with thrushes at the small end, small pigeons at the large end.) They have an elongated shape with an upright posture, which highlights their long tails. Their tails are often patterned on the underside (facing the viewer when the birds are sitting upright, facing forward). Males are typically more colorful than females. Males typically have more brilliant red, orange, or yellow underparts, with more brightly colored heads and chests, and perhaps iridescent green or blue plumage on the back (among African and New World species).

Trogons and quetzals have medium-sized heads and short necks, so they look like they’re hunching their shoulders. All trogons and quetzals have short, strong, slightly hook-tipped, wide-gaped bills. Many species have serrated mandibles — top and bottom bill parts — helpful for grasping fruit and other food. The bills of many trogons are adorned with rictal bristles (stiff feathers that look like short whiskers; highly responsive to flying insects). Their eyes are surrounded by unfeathered orbital rings (the bare skin encircling their eyes).

They have short, thin legs and feet, which are relatively weak, making it difficult to walk much more than shuffling a few steps along a branch. When they wish to turn around on a perch, they need help from their wings. Their leg muscles make up just 3% of their body — the lowest percentage of all known birds, about half as much as the percentage for most other birds. In contrast, their wing muscles are big and strong, about 22% of their body weight. Their short, broad wings enable trogons and quetzals to maneuver agilely, flying swiftly and efficiently through the surrounding trees, but usually not for long distances.

Figure 01b. It’s difficult to tell which are her first, second, third, and fourth toes, but this female Green-backed Trogon is turning her first and second toes backward and her third and fourth toes forward, unlike any other families of birds.

Unlike other birds, their toes are distinctively heterodactyl — the first and second toes turn backward, the third and fourth toes face forward. (The distinctive physiology of the trogons’ foot tendons may dictate this arrangement. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trogon#/media/File:TrogonPlantarTendon.jpg for more detail.) The most common birds — passerines (e.g., songbirds) — have anisodactyl toes (three toes point forward, one toe backward); parrots, woodpeckers, and some other birds have zygodactyl toes (first and fourth toes point backward, second and third toes point forward); both anisodactyl and zygodactyl toes can grip more strongly than heterodactyl toes.

In addition to their dainty toes, trogons have particularly thin skeletons, especially in the skull. Their skin is also quite fragile, and their feathers can easily be pulled out — handy when a predator tries to grab a trogon and ends up just with a mouthful of feathers. Human taxidermists and researchers have been disappointed by this tendency, too.

Well known for their ability to sit motionless for long periods, they can be hard to detect among the trees, especially if they turn their bright underparts away from view. Neither humans nor other predators can easily find them. Though not easily seen, trogons and quetzals can easily see others, both potential predators and potential edibles, as they can swivel their heads about 180̊.

Trogons and quetzals can be heard when making yelping, whistling, or “chuckling” calls (e.g., https://xeno-canto.org/species/Trogon-viridis , https://xeno-canto.org/species/Pharomachrus-auriceps ). Trogonidae seem to be highly responsive to the vocalizations of fellow trogons and quetzals, possibly indicating that these signal territory or have another social function.

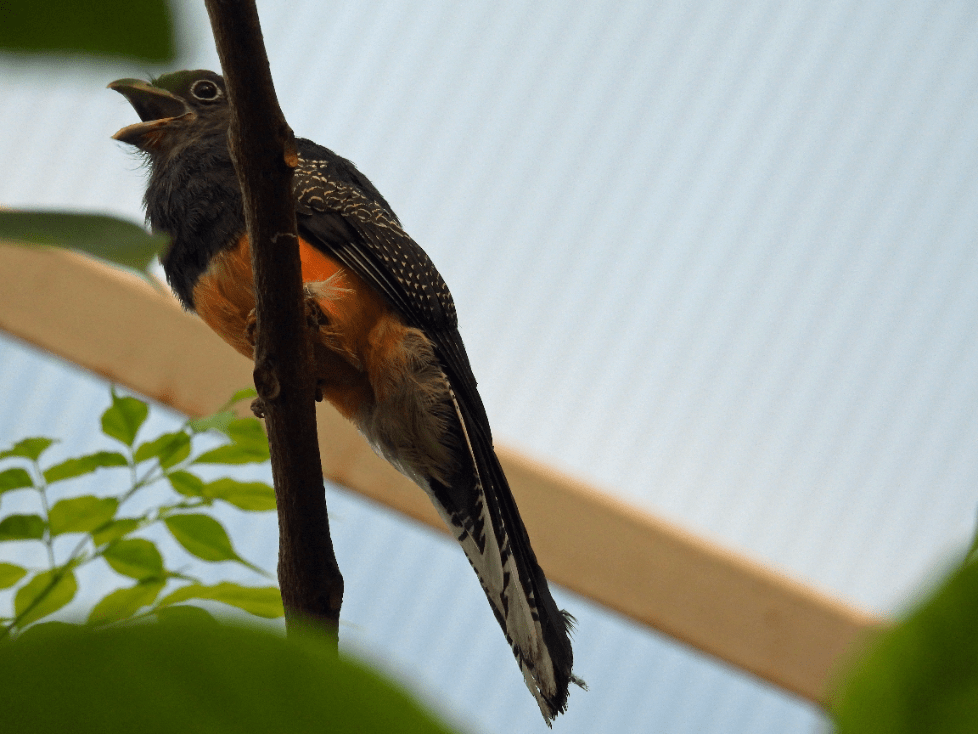

Figure 01d. In addition to being heard, many trogons can also be smelled — not only their excrement and their nests, but even their skin has a distinctive odor repugnant to most mammals. They probably acquire this smell by eating noxious caterpillars. Luckily, visitors to the Hummingbird Habitat at the San Diego Zoo don’t get close to this female Green-backed Trogon — or her poop.

In general, this family consumes fruits and invertebrates, as well as some small vertebrates, but they show regional differences. Quetzals of the New World eat almost entirely fruit most of the year; trogons there eat mostly fruit and insects (especially caterpillars) and arthropods, though a few larger trogons there also eat small vertebrates, such as frogs or lizards. Asian trogons eat proportionately more insects than New World trogons, and African trogons eat only insects.

Figure 01d, 1–2. These Green-backed Trogons (left) and this Golden-headed Quetzal (right) (residents of the San Diego Zoo) inhabit the neotropical zone of South America, but these trogons have a much larger range than this quetzal.

It’s probably not surprising that insect-eating trogons sally out from their perches to catch insects mid-flight or to glean them from branches or leaves. However, it may surprise you that a trogon will also sally out to grab fruits, plucking fruits while briefly hovering or even stalling in front of the fruit. Larger trogons, who grasp small vertebrates from the ground, will pounce on their prey from the air.

Though distributed widely (Asia, Africa, New World), trogons and quetzals prefer tropical and subtropical forests, though they’re sometimes found in mountain forests and arid woodlands. (The only trogon seen in the United States is the Elegant Trogon, which can be found in southern Arizona). They prefer the middle level of trees — “mid-story,” below the canopy but well above the ground, so they can easily search for food from their perch. In general, neither trogons nor quetzals migrate, but quetzals will move to higher or lower elevations sometimes.

All trogons and quetzals nest in cavities of varying depths, usually in cavities carved out by other species. They will, however, dig out their own nests when necessary, in a rotten tree trunk, a termite nest, or some other soft material. (Wasp-eating Violaceous Trogons will even raise their young in wasp nests!)

Figure 01e, 1–2. This male Green-backed Trogon apparently wasn’t satisfied with his inspection of the first nest hole and is carving out a second.

When a nest cavity must be excavated, typically either the male will do so alone, or both parents will do so. The female lays 2–4 eggs, and as soon as the last egg is laid, both monogamous parents incubate them (about 16–19 days). Trogon eggs are white or whitish; quetzal eggs are pale blue; no eggs have markings. After the eggs hatch, the blind and altricial (unable to care for themselves) nestlings are cared for by both parents until they fledge — typically, 23–25 days after hatching, but possibly 16–30 days.

Although the conservation status of 17% of trogons isn’t known, none are known to be Endangered or Critically Endangered; 4.3% are Vulnerable; 10.6% are Near Threatened; and 68.1% are deemed of Least Concern. In Central America, ecotourists pay to view quetzals, perhaps benefitting the local economies where they’re found.

At present, the Trogoniformes are believed to be more related to the orders Bucerotiformes, Coraciiformes, and Piciformes — and perhaps to the Coliiformes — as compared with other orders. Further studies often reveal other relationships. Fossils trace trogon ancestry to 49 million years ago, early in the Eocene. Much of what we know about trogons was revealed by the research of ornithologist Alexander Skutch (1904–2004).

Golden-headed Quetzal, Pharomachrus auriceps

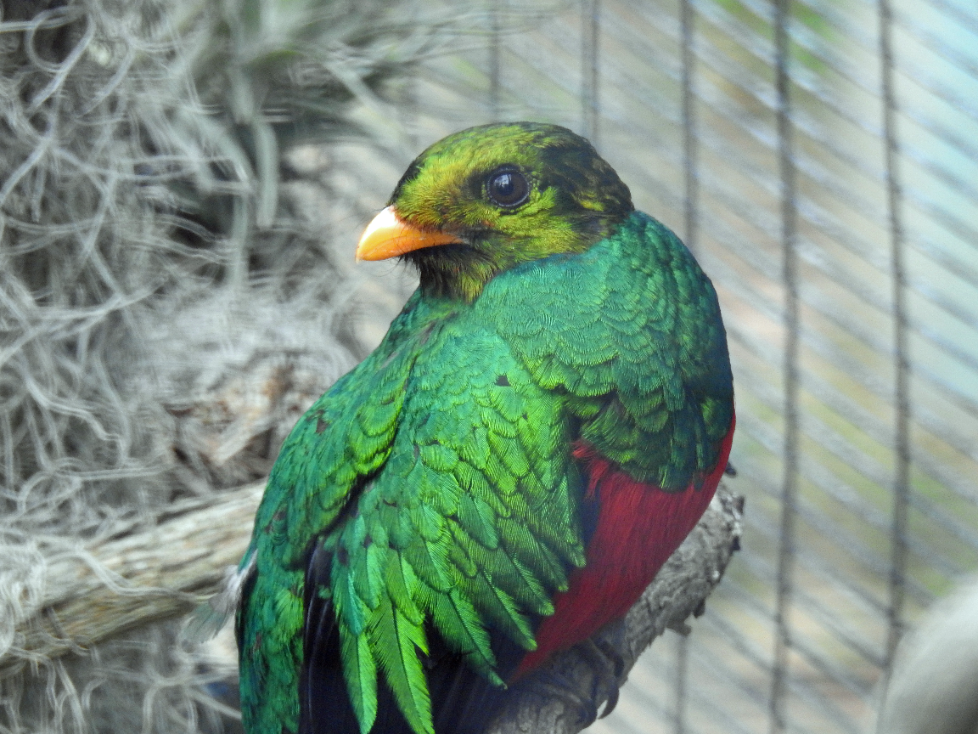

Figure 02a. The name quetzalcomes from the indigenous Nahuatl (Aztec language) name, quetzalli, alluding to the birds’ long tail feathers, longest in male Resplendent Quetzals. In Spanish, this quetzal species is Quetzal cabecidorado, “golden-headed quetzal.”

The scientific name for the genus of this quetzal, Pharomachrus, comes from the Greek pharos, meaning “cloak” or “mantle” and macros, meaning “large” or “long.” Its species name, auriceps, refers to its “golden,” auri, “head” or “crown,” -ceps. In John Gould’s 1875 second edition of A Monograph of the Trogonidae or Family of Trogons, Gould included this species of Trogonidae (https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/19543#page/258/mode/1up); Gould had named it Trogon auriceps when he first identified it in 1842.

Figure 02b. The black feathers underlying the metallic green feathers seem to enhance their shimmering beauty.

This quetzal is among the larger Trogonidae birds: 12.5–14″ (33–36 cm) long, with a comparable wingspan of 12–14″ (30–36 cm); the tail plumes of males can add up to 3.5–4″ (8–10 cm) to its length. These quetzals weigh 5.3–6.6 ounces (151–188g), with males tending to weigh about 1 oz. (30g) more than females. (A wooden pencil weighs about 1 oz.; a tennis ball weighs about 2 oz.)

Its back, chest, and upper-wing plumage is metallic green, its head plumes are bronze-green, complemented by brilliant red belly feathers and black feathers on the wings and interspersed with metallic green feathers on the tail. A stunning bird. Like other Trogonidae, the males are more vividly colorful than the females, but the females, with more brown plumes than males, still catch your eyes.

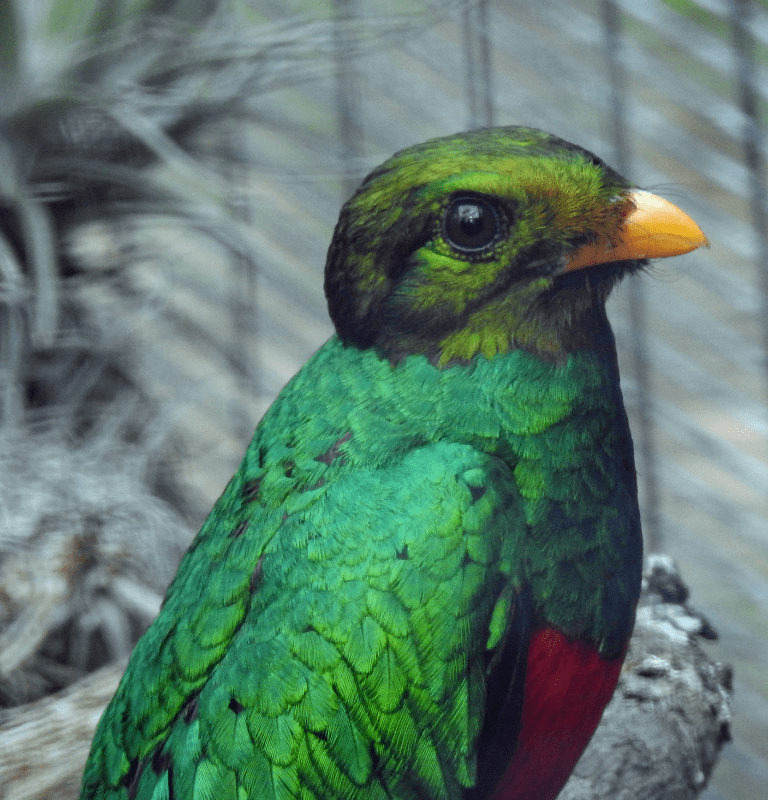

Figure 02c. Quetzals and trogons can sit motionless for long periods of time, ever watchful for predators.

Like other trogons, its head is relatively large, and the top of this quetzal’s head is relatively flat. Its short, wide golden bill is slightly decurved (downward) with a slightly hooked tip. A scattering of rictal bristles (short stiff feathers) adorn the sides of the bill, and facial feathers partly cover the top of the bill. Its orbital ring (skin circling its eyes) is narrow, bare, and black, so it’s not very noticeable (especially when compared with a Green-backed Trogon, for example).

Figure 02d. It’s hard to detect the bare skin of this quetzal’s orbital ring surrounding its eye, as well as the delicate tiny feathers surrounding the ring.

Though generally quiet, this quetzal can produce several differing kinds of vocalizations, from somber whistles to “Whoo-hoo” calls to what sounds like tittering or whinnying, and more. See https://xeno-canto.org/species/Pharomachrus-auriceps to hear the variety of vocalizations they’re known to produce.

This quetzal hugs the mid-elevation neotropics, 4000–10,000 feet (1200–3100m, but has been seen at 180–11,400 feet, 55–3,520 meters) especially along the Andes of northwestern South America, from northwestern Venezuela westward curving around through Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru to northwestern Bolivia, as well as Central America, such as in Panama. The forests preferred by the Golden-headed Quetzal include humid or wet cloud forests, dwarf and elfin forests, montane and foothill forests. This quetzal may stray onto open lightly forested areas in early morning, but it keeps to denser forests the rest of the day and night. It’s not known to migrate, but little is known about its movements.

A diurnal (daytime) eater, adults eat almost entirely fruits (85–90% of stomach contents; an Avibase source noted stomach contents as almost all fruit). Nonetheless, parents have been recorded feeding their nestlings insects and (rarely) small invertebrates. The plants in their territory benefit from the quetzals’ seed dispersal.

Figure 02e, 1–3. From any viewing angle, the Golden-headed Quetzal can take your breath with its stunning beauty.

Solitary most of the year, these quetzals pair up, monogamously, during breeding season. The male establishes a territory and entices his potential mate through singing. They apparently value their privacy, as their copulation has rarely been observed. Next, they search for either a suitable nest cavity or a suitable (slightly decayed) tree trunk they can excavate together, using their short, wide bills. The trick is to find a tree trunk soft enough to dig into but not so decayed as to fall apart while supporting a nest. They don’t dig very deeply, and while the birds are in their cavities, a tail or a head can usually be seen. They don’t line their nests.

After the female lays 1 or 2 pale-blue eggs, the male incubates them for one long daytime stretch, then the female incubates them the rest of the time, for about 18–19 days until the eggs hatch. Like all Trogonidae hatchlings, they’re born helpless, blind, and unfeathered. It takes about 3 days for the hatchlings (or hatchling) to develop juvenile plumage (mostly brown and black, with some green feathers on nape, throat, and upper back).

Both parents share in brooding the chicks (keeping them warm) for about 60–90% of the time during the first 8–14 days. Though both parents brood equal amounts of time, the female consistently broods at night; also, the dad may do more brooding when the chicks are younger and less brooding when they’re older. In any case, the parent who’s off the nest returns to the nest with food — usually insects, but also fruit — making a whinnying sound as it approaches, and the brooding parent flies off to find more food. What goes in must come out, and these quetzal parents keep a clean nest — typically by swallowing the chick’s droppings, but also by simply removing them.

After the two parents stop brooding the chicks (or chick), both parents continue with feeding, simply perching on the edge of the nest and leaning in to offer food. Eventually, the chicks will perch on the lip of the nest, waiting for a parent to deliver food. This continues until they’re about 25–30 days old and ready to fledge (fly for the first time). When the chick fledges, it perches on the front edge of the nest and simply flies away, though it may continue to stay in the area, near the nest, for awhile.

Figure 02f. To see more images of this magnificent bird, you can search the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library, which has 5,119 photos, 426 audio recordings, and 65 videos of this species. (See

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=gohque1&mediaType=photo&sort=rating_rank_desc ). In addition, the Lab’s eBird has records of 36,891 observations of this species.

When Aztecs and Mayans dominated Mexico, the tail feathers of these birds were often harvested (sometimes from living birds). The Aztec empire reigned over central Mexico from 1428 to 1521, and the Mayan empire reigned over southeastern Mexico from 2000 b.c.e. to a.d. 1697, but the descendants of both empires continue their heritage to this day. Nowadays, many people other than indigenous natives kill quetzals and trogons for their plumage, though habitat destruction causes greater perils for these birds.

The population of this species is declining, but given its large range (at least 7,700 square miles, 20,000 sq km, though some estimates are much greater), the lack of fragmentation of its territory, and its large presence within this range, this species is considered LC, Least Concern, by the IUCN — that is, not globally threatened. The global population is estimated at 50,000–499,999 mature individuals — a pretty wide-ranging guesstimate. The only conservation practice implemented for this species at present is continued monitoring; their cousin, the Resplendent Quetzal, has been shown to respond well to nest boxes. Survival rate is about 75% per year; maximum recorded age is 14 years. Generation length is estimated to be about 5.5 years, and age at first breeding is just slightly less than 2 years.

Green-backed Trogon, Trogon viridis

The scientific binomial (genus and species) name for this species is Trogon viridis, 1 of 24 in the genus Trogon. Naturalist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus named this species in 1766, choosing viridis, Latin for “green,” pointing to the iridescent green plumage on the male’s back. (According to Wikipedia, it had already been “described and illustrated in 1760 by French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson.”) Its name in Spanish: Trogón dorsiverde.

Figure 03a. From the side, in bright sunlight, it’s easy to tell which trogon is male and which is female (female, left in the left-hand photo; right in the right-hand photo). In dimmer light, it’s more difficult to tell, but the female has a more intricate undertail feather pattern.

The male’s iridescent green back feathers shift to blue-green as they reach his rump and descend to the top feathers of his black-tipped squared-edge tail. Males also have an iridescent bluish-purple crown, neck, and upper chest. These iridescent colors appear black when not highlighted by sunshine — an advantage when trying not to be seen by predators. The female’s feathers are mostly a rich chocolatey brown. When facing forward, males and females have bright yellow-orange belly feathers, and their undertail feathers are patterned with black or brown and white, the female’s pattern being more intricate than the male’s. Similarly, the female’s wings have intricate white patterning, whereas the male’s wings are iridescent green near the bird’s back and black reaching out to the wingtips. To avoid detection, these trogons face away from potential unwanted viewing. Their bills and their bare-skinned orbital rings (encircling their eyes) are whitish (actually pale blue, but not easily detected).

These trogon youngsters start out looking more like the adult female, but with more buffy or whitish areas on their plumage. Male youngsters soon develop some iridescent green feathers, especially on their backs.

Figure 03b, 1–2. When viewed from the side, this juvenile male looks a lot like mom, but when you see him in flight, you can see he’s starting to develop iridescent green feathers like dad.

These trogons are medium-sized birds, typically about 9.5–11″ (25–28 cm) long but up to 12″ (30 cm), weighing 2.5–3.75 ounces (74–107 g). A deck of playing cards weighs about 2.5 ounces, and a can of sardines in olive oil (or 21 quarters) weighs about 3.75 ounces. Males and females differ little in terms of body size (weight, overall length, tail length, tarsus length [leg length], wing length) or bill size (length, depth, width).

Their vocalizations sound like a staccato series of 15–20 calls; you can listen to numerous calls at https://xeno-canto.org/species/Trogon-viridis.

Figure 03-c, 1–2. This female (left) and male (right) can both be heard making several soft, staccato vocalizations in the Hummingbird Habitat of the San Diego Zoo. (I heard only 5–10 calls, not 15–20.)

This species of trogon inhabits a wide swath of neotropical Amazonia, east of the Andes and west of the Atlantic Ocean, throughout much of Brazil, the Guianas, Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, as well as separate populations in Trinidad and in southeastern coastal Brazil. Within its range (3–4.5 million square miles, 7.9–11.8 million sq km), it resides in the canopy or the subcanopy of various forest habitats — humid or wet forests, foothill forests, forest edges and clearings, even dry forests or swampy forests. It can be found from sea level up to about 4,300 feet (1,300 m, per Avibase) above sea level in many locations, even reaching 5,600 feet (1,700 m) in a few locations (according to the IUCN). Not known to migrate.

These trogons eat a mixture of fruits and arthropods, as well as (rarely) small vertebrates. These birds have been observed to eat stick-insects, beetles, grasshoppers, caterpillars (lepidoptera larvae), and occasional lizards. Analysis of the stomach contents of 29 birds showed 11 ate only fruits, 12 ate only arthropods, and 6 ate a mixture of both. Avibase estimates that 70% of their diet is fruit, 20% is invertebrates, and 10% is small vertebrates. Their consumption of foods other than fruits may depend on seasonal availability of fruit.

Like other trogons, they spend most of their time motionless, upright. They feed during the day as “aerial fugivores” (yes, “fugivores”) — plucking fruits on the wing. They’re fast fliers, but they seldom fly, very rarely much distance. Their heterodactyl toes and weak feet and legs make walking or hopping difficult, too. They mostly forage alone — usually 40–80 feet above the ground, but sometimes 22–131 feet (7–40 m). They occasionally (9% of observations) join mixed-species flocks to forage.

Figure 03d. Though these trogons have a marriage arranged by the San Diego Zoo’s Species Survival Plan (SSP), they seem to be making do with the arrangement.

Like other trogons, this species raises their young in nest cavities. References don’t make it clear whether one or both parents dig out the nest in an arboreal termite nest or another cavity in a tree — typically 30–100 from the ground (range, 7–130 feet). Once the nest has been excavated, the female lays 2–3 glossy white eggs in it. Presumably, like other trogons and quetzals, both parents participate in incubating their eggs (about 16–17 days) and brooding and feeding their young (about 19.5 days) until the fledglings fly away.

Figure 03e, 1–3. Though none of the references I studied indicated whether one or both parents excavated the nest cavity, at the San Diego Zoo’s Hummingbird Habitat, the male did most of the excavating (left and middle), with the female appearing to check his work (right), perhaps adding the finishing touches.

Though their population is declining (exact numbers aren’t known), the IUCN Red List considers them to be LC, Least Concern (2024), given their very large range. There aren’t identified conservation plans for them, but their range includes conservation sites. Unlike some other trogons, they’re rarely subject to trade. Annual survival is about 70% per year, and maximum known age is 12.5 years. Generation length is 3.8–4.5 years; age at first breeding is about 1.6 years.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird app lists 65,619 observations of this species (see https://ebird.org/species/gnbtro1). The Lab’s Macaulay Library holds 6,814 photos, 722 audio recordings, and 76 videos of this species (see https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=gnbtro1&mediaType=photo&sort=rating_rank_desc ).

References

Trogoniformes, Trogonidae

- Elphick, Jonathan. (2014). “Trogonidae” (pp. 414–416). The World of Birds. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books.

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, and Irby J. Lovette. (2015). “Trogoniformes,” “Trogonidae,” (pp. 211–212). Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Trogons (Trogonidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.trogon1.01

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trogon

Golden-headed Quetzal

- Collar, N. and A. Bonan Barfull (2020). Golden-headed Quetzal (Pharomachrus auriceps), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.gohque1.01

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden-headed_quetzal

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22682738/163902680 , Golden-headed Quetzal, Pharomachrus auriceps

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=A9525D744A915488&sec=lifehistory , Golden-headed Quetzal, Pharomachrus auriceps (Gould, J 1842)

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=F5215A345F45F831&sec=lifehistory , Golden-headed Quetzal (auriceps), Pharomachrus auriceps auriceps (Gould, J 1842)

Green-backed Trogon

- Collar, N., and G. M. Kirwan (2020). Green-backed Trogon (Trogon viridis), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.gnbtro1.01

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=BA2F0BFD

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green-backed_trogon

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22736238/263998450

Etymology of Bird Names

- Gotch, A. F. [Arthur Frederick]. Birds—Their Latin Names Explained (348 pp.). Poole, Dorset, U.K.: Blandford Press.

- Gruson, Edward S. (1972). Words for Birds: A Lexicon of North American Birds with Biographical Notes (305 pp., including Bibliography, 279–282; Index of Common Names, 283–291; Index of Generic Names, 292–295; Index of Scientific Species Names, 296–303; Index of People for Whom Birds Are Named, 304–305). New York: Quadrangle Books.

- Lederer, Roger, and Carol Burr. (2014). Latin for Bird Lovers: Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained (224 pages). Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Text and images (except Resplendent Quetzal) by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2026.

All rights reserved.

Leave a comment