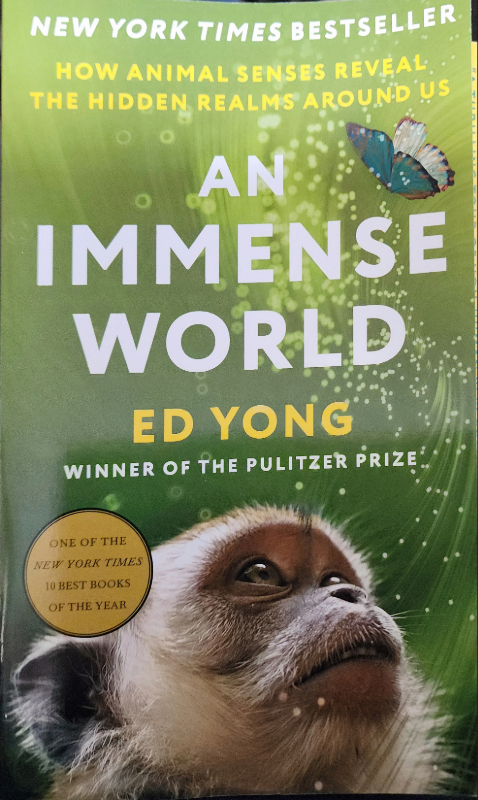

“An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us” by Ed Yong

Yong, Ed (2022). An Immense World : How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us. NY: Random House.

This is the third of three blogs discussing Yong’s book. Part 1 of these 3 blogs included Introduction: The Only True Voyage, 1–16; Chapter 1. Leaking Sacks of Chemicals: Smells and Tastes, 17–52; Chapter 2. Endless Ways of Seeing: Light, 53–83; Chapter 3. Rurple, Grurple, Yurple, 84–116; Chapter 4. The Unwanted Sense: Pain, 117–134

Part 2 of 3 discussed Chapter 5. So Cool: Heat, 135–155; Chapter 6. A Rough Sense: Contact and Flow, 156–187; Chapter 7. The Rippling Ground: Surface Vibrations, 188–209; Chapter 8. All Ears, Sound, 210–242

This third of three parts discusses the following chapters:

- Chapter 9. A Silent World Shouts Back: Echoes, 243–275

- Chapter 10. Living Batteries: Electric Fields, 276–299

- Chapter 11. They Know the Way: Magnetic Fields, 300–319

- Chapter 12. Every Window at Once: Uniting the Senses, 320–334

- Chapter 13. Save the Quiet, Preserve the Dark: Threatened Sensescapes, 335–356

- [back matter], 357–453

- Acknowledgments, 357–359

- Notes, 361–384

- Bibliography, 385–429

- Insert Photo Credits, 431–432

- Index, 433–449

- [about the author, 451]

- [about the type, 453]

Chapter 9. A Silent World Shouts Back: Echoes, 243–275

Only two groups of animals have perfected “biological sonar,” aka echolocation: bats and toothed whales (sperm whales, orcas, dolphins, etc.). Though bats aren’t blind, they have much more acute sensations through echolocation than through vision. Echolocation isn’t a second-rate sensation to vision, either. In some rainforests, bats catch and eat twice as many insects as birds do. By watching bats with infrared cameras, we can see their breathtaking maneuverability and acrobatic movements, easily zooming in on their flying prey (or other insects).

It wasn’t until the late 1930s that Donald Griffin showed that bats were using their ears to detect ultrasound frequencies and that they were also making ultrasound calls while they were flying. To fly effortlessly and swiftly through a labyrinth of wires, they needed both their mouths and their ears to send and receive ultrasonic calls — they were sensing their environment through echoes! In 1944, Griffin named this process echolocation.

Luckily, since Griffin’s day, technology has made it so much easier to study bats and echolocation: infrared cameras, miniature sensitive microphones, computer programs that translate inaudible sound frequencies into visible spectrograms, and so on. Even with these modern marvels, however, it’s hard for us humans to truly imagine the Umwelt — sensory world that an animal experiences — of a bat.

Echolocation is an active sense. The bat (or other animal) must send a signal for it to echo back; no signal sent, no echo back. Another consideration: Bat signals are in the high frequency range, and high-frequency sounds dissipate quickly, so they don’t carry over long distances. In the air, a bat can sense a large moth only about 11–13 yards away, and a small moth even less, about 6–9 yards away. A huge human can be detected at larger distances, but bats are much more keenly interested in moths. Bats also send their signals as sort of a cone, like the light from a flashlight on a dark night. The signals at the edges of the cone are fuzzier, and outside of the cone, they’re undetectable.

Bat signals are LOUD!!! — 110–138 decibels (dB), up to about as loud as a siren or a jet engine — among the loudest sounds of any land animal. We humans don’t hear them because they’re ultrasonic. But bats can hear these sounds. Why aren’t they deafened by their own calls? They contract the muscles of their middle ear’s muscles as they send out each signal, and they relax those muscles to receive the bounced-back echo. That’s not easy, either! Bat vocal muscles contract and expand up to 200×/second — the fastest mammalian muscle speeds on Earth! Luckily, their vocal muscles only reach those extreme speeds when they’re getting close to their targets. Bats can also adjust their hearing sensitivity as they get closer to a target, so that it’s not too loud when they get nearer.

Those extreme signal speeds create an additional problem, though. While zipping through the air, vocalizing, and receiving echoes, the bat must be able to match each outgoing signal to each echo in order to interpret each received signal. It helps that each outgoing signal is only a few milliseconds long. Even at 200 signals/second, there are long-ish gaps between signals. Bats further separate the signals by pausing to receive an echo before sending a new signal. They time their signals so that at any one instant, they’re either sending a signal or receiving an echo — never both. And all of that at lightning speeds. “The bat’s nervous system is so sensitive that it can detect differences in echo delay of just one or two millionths of a second, which translates to a physical distance of less than a millimeter” (p. 250, emphasis added).

Bats vary their signals slightly in order to reveal more about an insect’s shape, size, orientation, and texture, as well as location. Bats also vary their signals depending on their distance from their targets. Bats use long and loud signals for detecting prey at a distance, but shorter, quieter, more complex signals as they approach their prey. And all of this usually happens within seconds, from initial sweeping search to final capture.

Bats also use distinctive calls when negotiating their way through a cluttered environment such as a forest or a cave. They also have distinctive call strategies when flying in large flocks, such as when going to or from their roosts. They avoid overlapping their own calls with those of others, by changing their sound frequencies or varying their timing.

To summarize: Echolocation is mentally demanding and energy consuming, especially when being done while flying speedily. Yet bats are highly successful: One of every five mammal species is a bat, and bats can be found on all continents except Antarctica. Of the 1,400 species of bats, all fly, and most of them echolocate, though some don’t.

Figure 01. This Rodrigues fruit bat, photographed in the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park, doesn’t have to work very hard to find fruit, unlike its cousins, who must work hard to echolocate enough flying insects to feed itself.

Most echolocating bats can modulate the frequencies of their sonar pulses, adjusting the pitch (higher or lower), using brief (1–2 millisecond) pulses separated by long pauses. About 160 species of echolocating bats use a different strategy. Instead of using a range of frequencies, they use just one frequency for their pulses, which last a few hundredths of a second, interspersed with short pauses. Bats using a constant frequency can more readily detect a distinctive sound made by an insect’s wing, which reveal’s the insect’s species and its direction of movement.

Moths aren’t defenseless, however. For one thing, more than half of moth species have ears that can detect bat sonar. (The Part 2 blog briefly discussed moths’ hearing ability: https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/24/sensational-animals-part-2/#moth-hearing) In fact, these moths can detect the approach of a bat about 15–33 yards away, whereas bats can’t detect moths until they’re about 6–13 yards away. These sonar-detecting moths may be able to beat a swift retreat.

In addition, an entire group of about 11,000 moth species — tiger moths — can go one step more to defend themselves. Tiger moths can produce their own ultrasonic clicks, which seem to disrupt bat sonar. Luna moths take a different approach. They have no ears and no mouths, but they do have long tails at the end of their hindwings; these tails twirl and flap as the moths fly, creating confusing echoes for bats.

Figure 02. Luna moths neither produce nor detect echolocation signals, but they have an effective way to avoid detection by bats.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luna_moth#/media/File:Actias_Luna_Fieldbookofinsec00lutz_0195.jpg. English, Illustration from Field Book of Insects. Date, 2 January 1918. Source, https://www.google.com/search?q=Edna+Libby+Beutenm%C3%BCller&sxsrf=ACYBGNRxBZaqmQegGjCbID2khbm865yzrA:1575746569474&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjo6Z20oaTmAhUEvVkKHdPrA_YQ_AUoAXoECA4QAw&biw=1342&bih=732#imgrc=PeXkgH3zs0EW1M: Author, Edna Libby Beutenmuller. Licensing: Public domain. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or fewer. See also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luna_moth

Bats and dolphins look nothing alike, and while one moves through air over land, the other moves through water in the deep ocean. Yet both must navigate through three-dimensional space in darkness or near-darkness much of the time. And both developed the same strategy for doing so, using echolocation.

It’s easier to study bats than dolphins: Creating an environment suitable for studying bats is much easier than creating one suitable for studying marine dolphins. It’s nearly impossible for researchers to naturalistically observe dolphins in their habitats, so most studies are done either in existing large aquariums or in naval facilities. Dolphins are also much smarter than bats, which may seem like a good thing, but they’re also more willful. If a dolphin doesn’t want to do something or to learn a particular behavior, . . . the dolphin won’t. Nevertheless, researchers persist — fortunately for us. Persevering researchers sometimes use an acoustic tag — basically, an underwater microphone with suction cups, which they attach to a dolphin when it surfaces.

Using echolocation, dolphins and other toothed whales can identify objects not only by shape and size, but also by material — even distinguishing between brass and steel or between glycerine-filled cylinders and alcohol-filled cylinders. They can also reliably find particular objects through “several feet of sediment” (p. 262). In one instance, researchers presented two “identical” cylinders to a dolphin, who insisted the cylinders differed. After rechecking, the researchers found the dolphin was right — one cylinder was 0.6 mm wider at one end. The U.S. Navy invests in studying and training dolphins because “the only sonar the Navy has that can detect buried mines in harbors is a dolphin” (p. 262).

The previous chapter (in Part 2, https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/24/sensational-animals-part-2/#baleen) highlighted the remarkable infrasound hearing of filter-feeding baleen whales (mysticetes). Infrasound waves have extremely low frequency; in contrast, echolocation uses ultrasound, with extremely high-frequency waves. Toothed whales (odontocetes) — porpoises, belugas, narwhals, orcas, and sperm whales, as well as dolphins (73 species total, per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toothed_whale) — use ultrasound for echolocation.

Echolocation can create a rich 3-D sensation of an object, not just like seeing with sound, but almost like touching with sound. Almost by definition, echolocation is an exploratory sense, reaching out to sense the environment and the objects in it.

Most toothed whales produce clicks by forcing air through phonic lips, located in their nasal passages just beneath their blowhole. The lips’ vibrations do not, however, go out through the blowhole. Instead, the sound vibrations move forward through the toothed whale’s melon, a fatty organ that focuses the sound and transmits it into the sea water in the desired direction, at the desired rate and intensity.

Figure 03. Dolphins and other toothed whales (odontocetes) produce clicks in their noses, focus and transmit the clicks through their forehead, and receive the echoes through their jaws, where they transmit the echoes to their inner ears.

Source: This file was derived from: Toothed whale sound production.png. Author, Jooja. Created with Inkscape. Date: 25 November 2020. Licensing: w:en:Creative Commons. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. You are free: to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toothed_whale#Echolocation

The process is more complicated for sperm whales — the largest of the toothed whales — which produce the loudest sound of any animal on Earth — 236 decibels (dB). (According to https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/70669-loudest-animal-sound that’s 44× louder than the sound of a thunderclap, and this ultrasound can carry dozens of miles through dense seawater. All sound travels faster and farther in water than in air, but that’s still impressive, given that high-frequency ultrasound doesn’t transmit far before it dissipates. For more information about echolocation in sperm whales, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sperm_whale#Vocalization_complex. For human ears, according to https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/noise-induced-hearing-loss, long or repeated exposures to sounds above 85 decibels can cause hearing loss, and the louder the sound, the less time it takes to lose hearing.)

Okay, so toothed whales produce clicks with their noses, and transmit clicks through their foreheads. What next? They sense the echoed clicks with their lower jaws (mandibles). Their lower jaw is actually a hollowed bone filled with acoustic fats just like those in the melon. This time, the fats help to channel the sound backward toward the inner ear.

The fact that sounds travel faster and farther through water than through air makes echolocation more powerful for odontocetes than for bats. A bat’s prey must be pretty close for it to be sensed through echolocation, but “echolocating dolphins can detect targets from over 750 yards away” (p. 266). Also, whereas a flying bat has less than a second to respond to echoed clicks, a swimming odontocete may have about 10 seconds to respond, allowing it to consider more carefully its prey and how to approach it.

Sound not only travels through water faster and farther, but it also reacts differently to objects in water. In the air, sound waves bounce off of any solid surfaces. In water, however, sounds will penetrate flesh then bounce off bones or even pockets of air. (Think about ultrasound scans of fetuses in utero.) This property allows dolphins to use echolocation to see inside their prey, detecting their skeletal structure or their lungs. When pursuing fish, dolphins can detect their air-filled swim bladders, for controlling buoyancy. Dolphins can probably distinguish among fish species, noticing distinctively shaped skeletons and swim bladders.

In addition, it’s no accident that many toothed whales hunt prey in pods or teams. They can coordinate their actions and use echolocation not only to find prey, but also to encircle prey. They can use their sonar to act as one unified predatory force.

Another echolocating mammal may surprise you: a human. Daniel Kish was born in 1966, and by age 13 months, he was blind in both eyes. While still a toddler, he began to make crisp loud clicking sounds (similar to loud finger-snapping) and to listen to their echoes back. By the time he could walk ably, he could click ably, and he’s been doing it ever since. “Kish walks briskly and confidently, using a long cane to sense obstacles at ground level and echolocation to sense everything else” (p. 269). He also amplifies his echolocation by using other tricks used by other blind people, such as keeping things in routine places and remembering those places.

Kish’s human sonar can never be as acute as a bat’s or a dolphin’s, and he can’t detect clearcut edges to objects. He can see surfaces that slope upward better than surfaces that slope down. Harder surfaces and angled objects are easier to sense than softer surfaces and curved objects. Nonetheless, Kish’s echolocation enables him to move freely in the world, without a companion. He can also sense objects behind him, “see” around corners, and even peer through walls. Lore Thaler, a neuroscientist who studied Kish’s brain, revealed that parts of his visual cortex are highly active when Kish is using echolocation. That is, Kish uses his visual cortex to make spatial maps of his environment.

Kish isn’t alone in using echolocation; other blind people do so now and have done so in the past. What’s more, Kish founded World Access for the Blind, a nonprofit dedicated to helping other blind people to use echolocation. Since 2000, his organization has “trained thousands of students in dozens of countries” (p. 274).

A few other mammals and at least two birds (the cave-dwelling oilbird and the swiftlet) also use at least some echolocation, though not to the extent or the sophistication of bats or odontocetes. They use it for navigation rather than to catch prey.

In Yong’s view, the most distinctive thing about echolocation is that it’s always active, exploratory, never passive.

Chapter 10. Living Batteries: Electric Fields, 276–299

For electrical conduction to work, the animal must be immersed in some kind of conductive medium, such as water. Air is an electrical insulator, so any animals living out of water would be less able to receive electrical signals, even if they had electroreceptors. Among fish, 1 of the 350 species that not only senses electricity but also produces it is an electric catfish, which can generate about 90 volts — enough to hurt but not to electrocute a human. Another is the torpedo ray, which was described by ancient Greeks and Romans, who commented on its ability to numb any body part within its range.

Electricity-generating fishes evolved through modifications of their muscles and nerves to form specialized electric organs (not found in concert halls). These electric organs comprise numerous electrocyte cells, stacked sideways in the muscle or nerve. “By controlling the flow of charged particles called ions through an electrocyte, a fish can create a small voltage across it. And by lining these cells up and triggering them together, it can combine the minuscule voltages into substantial ones” (p. 277).

Probably best known among electricity-generating fish is the electric eel; a 7-foot-long eel will have about 100 stacks of 5,000–10,000 electrocytes each. One species of these eels can generate 860 volts of electricity. (A standard household outlet delivers 120 volts of electricity; a human body will be harmed by voltage above 50 volts.) All of these eels can use their electricity to trigger the muscles of its prey to twitch, alerting the eel to its location. A few stronger pulses, and the prey’s muscles are paralyzed, making it easy to catch. Yong compared the eel’s electric organ to a remote-controlled Taser.

Electric eels, electric catfish, and torpedo rays can generate enough electricity to numb prey or an approaching predator. In addition, two other types of fish generate weaker electricity: elephantfishes (African mormyroids) and knifefishes (South American gymnotiforms). What do they do with their weak electricity generation? They use it to sense their environments, as well as to communicate with one another. They sense electricity to understand their environments, their Umwelt.

For instance, a knifefish generates electricity in the electric organ in its tail. When the fish turns on its electric organ, it surrounds itself with its own electric field, its current flowing through the water. The instant it switches on its electric field, it’s in electric contact with its surroundings. Unlike light, sound, or echoes, electric fields don’t travel.

As soon as the fish turns on its electric field, it can sense its surroundings through thousands of electroreceptors. These electroreceptors transmit electric sensations to its brain — an organ that uses electricity to process information. This sensing has been called active electrolocation (reminiscent of echolocation). The fish’s electroreceptors can identify objects that are insulators (e.g., rocks), which do not conduct electricity; insulators reduce the current, creating sort of an electric shadow. More importantly, the electroreceptors can sense living animals, filled with salty liquid, an excellent conductor of electricity, increasing the current — sort of an electric spotlight.

Like echolocation, electrolocation requires active effort on the part of the animal; unlike echolocation, electrolocation is sensed immediately, without a need to wait for an echo. Also, whereas echolocation is sensed as sound, electrolocation is probably sensed as touch.

Knifefish can easily detect salinity, too. They rely on comparing the salinity of the water with the salinity of their prey. With its electric organ switched on, the knifefish can detect the conductivity, position, size, shape, and distance of objects in its environment. The electric field completely encompasses the fish in all directions, so the fish can deftly move in any direction, including tail-first.

Big drawbacks: Electric fields dissipate a short distance away from the fish. Generating electric fields is energy intensive — consuming about 1/4 of the fish’s total calories. If the fish wanted to double the size of its electric field, it would have to spend 8 times as many calories. Electrolocating fish need to respond quickly to their sensations, moving swiftly and agilely — even to swim in reverse, as needed.

The good news: Electrical sensations aren’t disturbed by darkness or murkiness or barriers or even water turbulence. And there’s no hiding from electrolocation; if you’re alive, you can be detected. Electric fields are also great for communication. They’re instantaneous and don’t need time to travel between communicators. Obstacles don’t absorb them or distort them; they don’t echo and can’t be “overheard” by outsiders. Electric fish can swiftly turn their fields on and off, creating precise rhythmic pulses, which they can vary in duration, frequency of transmission, voltage, and more. Receiving communication doesn’t require a lot of energy either; if both fish have potent electroreceptors, they don’t need to use as much energy as they would when trying to electrolocate.

Fun quote: “Convergent evolution, different groups of organisms accidentally show up at life’s party in the same outfits” (p. 295, emphasis added).

Sharks and rays can’t generate electric fields, but they do have electroreceptors — mostly around their mouths. Why? Because when their other senses aren’t easily detecting nearby prey, they can use their electroreceptors to detect the presence of highly conductive living animals. That is, sharks and rays have passive electroreception, which works when prey animals are very close. A shark will use its sense of smell to sniff out food from miles away, then as it gets a fairly close, it can see its prey, then when it gets within a few feet, its passive electroreceptors guide its mouth to its prey.

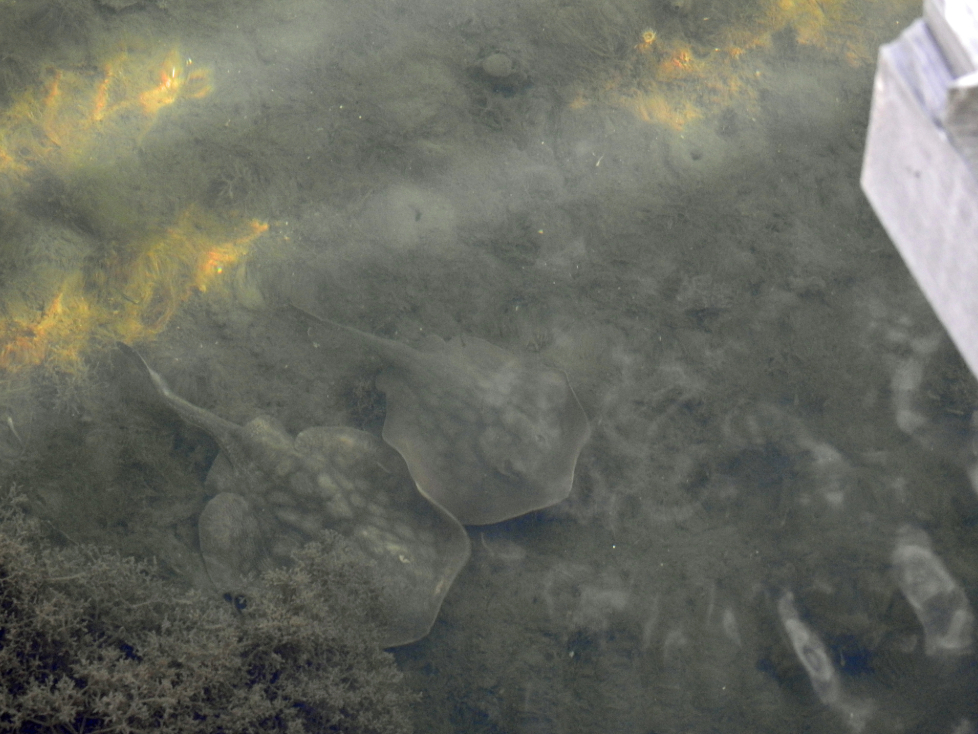

Figure 04 (a,b). These rays (1 left, 2 right) appear to be electric rays (in the cartilaginous fish order Torpediniformes, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electric_ray, part of the Batomorphi division, per Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Batomorphi). I welcome your comments and suggestions if I’m mistaken. I hope I’m correct; if so, scientists named them as torpedo-shaped rays among the bat-shaped rays. If they are electric rays, not only do they have passive electroreceptors, but they also generate electricity of 8–220 volts, depending on the species of electric ray. (Photographed at Bolsa Chica Ecological Reserve, Thursday, May 18, 2017, 9:17:36 AM.)

Among vertebrates, the electroreceptors seem to be situated within a chamber filled with an electrically conductive jelly-like substance. Atop the chamber, on the surface of the animal, is a pore allowing electrical fields to be conducted to the electroreceptors.

Some other vertebrates can detect (but not produce) electrical fields, too: salamanders and caecilians (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caecilian for more on this worm-shaped amphibian). At least three mammals also have electroreceptors, but it’s not clear how two of them use these sensations. Marsupial echidnas have electroreceptors at the tips of their snouts, for rooting around in moist soil, and a species of dolphin has some electroreceptors — which seem superfluous for an echolocating mammal.

The most impressive electroreceptive mammal is the water-dwelling platypus, which has more than 50,000 electroreceptors in its bill. These electroreceptors detect electrical signals emitted by potential prey. Its bill also has myriad touch receptors sending signals to its brain. The brain of a platypus dedicates more space to processing its bill’s sensory receptors than all the receptors anywhere else on its body. The platypus’s brain combines electrical and touch sensations into a unified sense of “electrotouch” sensation to find prey. While trying to locate prey, platypuses close their eyes, ears, and nostrils, minimizing any other sensations while sweeping their bills side to side. Its brain may also use precise time information. For instance, how long between when it senses a crayfish’s electrical field and when it senses movement of water created by the crayfish? The time lag may indicate distance from the crayfish.

Among invertebrates, spiders can sense Earth’s electrical fields. Surprisingly, many spiders can use electrical charges — for transportation! A spider can extend its legs upward, raise its abdomen, and extrude silk skyward; the silk has a negative charge as it leaves the spider’s body. Nearby plants also have a negative charge, repelling the spider upward. (Opposite poles repel each other.) Add a slight breeze, and the spider’s silk can “balloon” the spider upward and away over long distances.

Figure 05. I would welcome your help to identify this lovely orb-weaver spider in its web. (For some fascinating information on spider silk, please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spider_silk

At least some bees may also be able to detect electrical fields. The tiny “hairs” that make them look fuzzy are mostly tuned to sensing movements from air currents, but they also respond to electrical fields produced by some flowers. It’s also possible that at least some flowers use electrical energy to disperse pollen onto nearby pollinators.

Chapter 11. They Know the Way: Magnetic Fields, 300–319

Nocturnal Australian bogong moths seem to sense the Earth’s magnetic field to guide their migrations. Even spiny lobsters, cardinal fish, flatworms, and mud snails also have magnetoreceptors for detecting Earth’s magnetic field.

Figure 06. Monarch butterflies (a) and bogong moths (b) are the only insects known to migrate long distances annually. Whereas the diurnal monarchs do so mostly by sight, nocturnal bogongs mostly rely on their sensations of Earth’s magnetic field.

Source for (b): Agrotis infusa (Boisduval, 1832), to MV light, Aranda, ACT. Date, 4 October 2008, 12:00. Author, Donald Hobern from Canberra, Australia. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. You are free to share under the following conditions: attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bogong_moth

Sea turtles (e.g., loggerheads) have two types of magnetoreceptors to guide them to their birthplace after roaming more than 1,000 miles from it. Specifically, sea turtles can detect two properties of Earth’s magnetic field. The intensity of the magnetic field varies at different locations on Earth, so detecting magnetic intensity is one location clue. A second clue comes from the inclination of the magnetic field — the angle at which the field meets Earth’s surface. At the poles, the magnetic field is perpendicular to Earth’s surface, whereas at the equator, it runs parallel to it, with varying angles between the equator and the poles — indicating latitude. By integrating these two clues, sea turtles can figure out their exact location.

Like sea turtles, salmon imprint on the magnetic field of their birthplace, then as adults, the salmon are helped by their magnetoreceptors (and smell receptors) on their epic return journeys to their natal streams. Manx shearwaters (seabirds) use magnetoreceptors to find their way home, too. Countless migratory songbirds (e.g., blackcaps, European robins, garden warblers, goldcrests, indigo buntings, silvereyes, white-throats) also have magnetoreceptors. These songbirds transmit magnetic sensations to the visual processing centers of their brains. There, they may orient their visual sensations with magnetic ones, like a visualized compass.

Earth’s magnetic field may even guide the migration of gray whales. A study tracking when solar storms disrupt Earth’s magnetic field found that otherwise healthy whales were four times more likely to beach themselves when solar storms were most intense and therefore most disruptive.

Though magnetic fields are more useful in guiding long-distance travels than short hops, big brown bats use magnetoreception to find their home roosts after a long night of hunting insects, and mole-rats use it to navigate the intricacies of their underground burrows.

Magnetic fields are notoriously hard to control or to detect in a laboratory setting, which makes research challenging. In addition, because magnetic fields readily pass through an animal’s body, magnetoreceptors can be located absolutely anywhere on the animal. So far, scientists haven’t been able to locate them. That makes it tough to figure out how magnetoreceptors work.

Meanwhile, researchers have come up with some possibilities. One is that somewhere in the animal’s body (such as a bird’s bill) are some tiny crystals of magnetite (a magnetic iron mineral), which magnetoreceptors could use for sensing magnetic fields. A second option might work in birds, too: Their inner ears contain a conductive fluid, which might induce a magnetic sense while the bird is flying, triggering its magnetoreceptors. Perhaps some aquatic animals could use some electromagnetic induction in this way, too. A third option involves a magnetic chemical reaction in body cells (e.g., “cryptochromes”) of an animal, such as the eyes of a bird. This option suggests that birds can actually see Earth’s magnetic field; initial research seems promising, but further study is needed.

Though mechanical compasses are precise and reliable, “biological compasses are inherently noisy” (neither precise nor reliable). Animals who use magnetoreception also use other senses, such as vision and smell. Yong concludes, “I have no idea how to begin thinking about the Umwelt of a loggerhead turtle” or other animal using magnetoreception (p. 318).

Chapter 12. Every Window at Once: Uniting the Senses, 320–334

Much to our chagrin, mosquitoes (e.g., Aedes aegypti, transmitter of Zika, dengue, yellow fever) take a multisensory approach to finding the blood of their prey — humans. We emit not only smells, but also carbon dioxide and heat. Actually, CO2 is their main clue, and none of us are willing to stop breathing in order to avoid mosquito bites. Once they land on us, taste (detected through mosquito feet) is another clue. The mosquito’s Umwelt is multisensory, as is ours and the Umwelten of other organisms.

“Each sense has pros and cons, and each stimulus is useful in some circumstances and useless in others” (p. 323). More than one sense is vital to understanding and surviving in an environment (smart-sniffing dogs have big ears; superb-hearing owls have big eyes; big-eyed jumping spiders detect surface vibrations; etc.). Synesthetes can even have their sensations integrated (hearing colors, seeing sounds, etc.). For example, the platypus’s sense of electrotouch integrates sensations from its electroreceptors and its mechanoreceptors. Some insect antennae may integrate smell and touch sensations.

More often, sensory information is integrated in the brain, not the sensory organ, such as when a dolphin integrates what it senses through echolocation with what it sees. Bumblebees seem able to integrate visual and touch information to distinguish objects.

Some of our senses are vital to our survival, but nearly imperceptible to our conscious awareness. Proprioception tells us about our body’s position and movements, making it possible to locomote or even to sit. Equilibrioception — our sense of balance — is crucial to maintaining an upright posture, as well as moving through space.

Figure 07. This gawky human is able to move across the pool (however awkwardly!) because of her senses of proprioception and equilibrioception.

Our sensory organs must try to make sense of our Umwelt, despite there being two kinds of stimuli: Exafferent stimuli are sensed passively, caused by things and events that happen in the world, with no help from us. Reafferent stimuli are caused by our actions, such as when we turn our heads or move through space. Both kinds of stimuli are sensed in exactly the same way. How can we — or any organism — tell the difference? We detect the difference because our bodies send messages to the brain whenever we move our muscles, and our brains integrate those messages with the multiple messages coming from our sensory organs. And all of this happens outside of our conscious awareness.

Fun fact: This dual processing of our body’s actions and of our sensory organs’ stimulation is vital to survival for all creatures, but it does have at least one drawback: We can’t tickle ourselves because our brains know it’s our own actions causing those touch sensations.

The Umwelt of an octopus may seem alien to us. An octopus’s nervous system has about 500 million neurons, but only about 160 million of them are in its head, where its brain processes information from its eyes. The other two thirds are located throughout its eight arms, each arm acting independently or working together for coordinated actions. Each arm also has 300 suckers, each of which seems also to behave independently. On each sucker are about 10,000 mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors for sensing touch and smell. These sensations are probably inextricably integrated by the sucker’s “sucker ganglion” — sort of a mini-brain. None of the sucker ganglions communicate with each other, but all of them send and receive information to and from the “brachial ganglion” for the whole arm. Each arm’s brachial ganglion can prompt the suckers to coordinate to grasp things, probe things, or whatever other action is desired. Each arm’s proprioceptors seem to report to the brachial ganglion, not to the central brain.

The octopus’s central brain can control and coordinate all eight arms, such as to grab prey or to avoid a predator, but most of the time, each arm is free to move and to explore on its own. Also, though the arms are primarily responsive to touch and smell, the central brain seems to be more tuned in to visual sensations. And the whole is more than the sum of its parts. The octopus’s central brain can coordinate the solution of a problem that an individual arm can’t solve.

Almost always, our sensory processes occur outside of our conscious awareness. We rarely think about our sensations unless something has gone awry. Our senses are so fully embodied that they’re un-conscious. Given that we’re so unaware of our own sensory processes, it’s not surprising that we have trouble conceiving of the Umwelten of other organisms. Even when we can analyze sensory organs, identify senses, infer senses from behavior, we really can’t sense the world of other organisms. But it’s fun to try to do so.

Chapter 13. Save the Quiet, Preserve the Dark: Threatened Sensescapes, 335–356

In this, the geological epoch named the Anthropocene — due to our outsized impact on the planet — we seem to be precipitating the mass extinction of myriad species of animals and other organisms. We’re certainly imperiling the delicate ecosystems of Earth with the fossil-fuel-generated climate crisis. In addition, we’re impacting the environment in countless subtler ways, as well.

“We have filled the night with light, the silence with noise, and the soil and water with unfamiliar molecules” (p. 336). In 2001, it was estimated that two thirds of the people on Earth lived in light-polluted places. Just 15 years later, about 83% people lived with light pollution, and more than 99% of Americans and Europeans did. Almost 80% of North Americans can’t see the Milky Way, even on a dark night.

Of course, we should be doing all we can to mitigate the climate crisis and to minimize and even remediate pollution of the air, the water, and the land. And we should absolutely work hard to minimize the extinction and population decline of living organisms. In addition, we should also find ways to minimize the harm we cause by interfering with the sensory Umwelt of the organisms in our environments.

Of particular concern is light pollution during the semiannual migration (spring and fall) of billions of birds. As it is, migration pushes birds to their physiological limits, and many migrating birds perish from exhaustion, starvation, or other causes. We shouldn’t be adding to their burden, pushing them beyond their physiological limits. Researchers estimated that 7 million birds die each year by crashing into communication towers alone.

Other victims of light pollution are sea turtle hatchlings, who rely on moonlight to guide them to the sea. When seaside towns and resorts shine night lights during hatching season, they confuse the hatchlings, who either die of exhaustion or fall victim to hungry seabirds, before reaching the sea. Nocturnal insects are also harmed by outdoor night lights. “A single streetlamp can lure moths from 25 yards away” (p. 341) and will probably be eaten or will die from exhaustion trying to escape it. Artificially lit gardens reduce pollinators’ visits by 62%, so flowers, too, are harmed. (See https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/15/the-secret-network-of-nature/#moths-light for how light pollution affects moths and other nocturnal insects.)

Ideally, we can minimize the use of outdoor night lights (or indoor night lights if visible outdoors). Perhaps replacing constant night lights with motion-detector lights, or at the least, point lights downward, not radiating upward into the sky. The color of the lights makes a difference, too. Blue lights and white (full-spectrum) lights are the worst pollutants. Yellow lights don’t bother turtles or insects, but they do affect salamanders. Red lights don’t bother bats or insects, but they do affect migrating birds. Think about where the lights are located and which organisms would be most greatly harm by the lights.

Many of the animals who are harmed by light pollution are also harmed by noise pollution. Noise pollution harms any of the animals who rely on sound for communication, for finding prey, for finding mates, and so on. Even in protected areas such as national parks, the noise of human activity doubled the background noise in nearly two thirds of the parks tested, and multiplied that noise by 10 in about a fifth of the parks. These LOUD background noises make it hard for owls to find prey, for songbirds to find mates, and for prey to detect the approach of predators. During challenging times — such as when migrating, incubating and raising nestlings, lean times — many birds aren’t able to survive the added burden of noise pollution. Noise pollution is hard to escape, too. “More than [83%] of the continental United States lies within a kilometer of a road” (p. 345).

Noise pollution is even more harmful to many marine animals, who rely on infrasound, echolocation, sound, and ultrasound to navigate, find prey, avoid becoming prey, find mates, and provide for their young. In addition to the near-constant loud noises of fossil-fuel-powered ships, marine animals must contend with “the scrapes of nets that trawl the seafloor; the staccato beats of seismic charges used to scout for oil and gas; the pings of military sonar” (p. 345).

Just a few additional ways in which we pose challenges to animals:

- Smooth vertical surfaces (such as skyscrapers) return bat echoes, simulating open air

- Plastic waste in the ocean smells like DMS, the chemical released by plankton, attracting seabirds, sea turtles, and whales to consume it (about 90% of seabirds’ bellies contain plastic waste)

- Speedboats ripping through the waters where slow-moving manatees are living cause at least a fourth of the manatee deaths in Florida

- Pesticides released into rivers weaken the senses of salmon trying to swim to their natal waters

- Pesticides that reach the ocean are consumed again and again, working their way up the food chain

- Radioactive waste continues to kill for millennia before degrading

Some animals have managed to adapt to human intrusions, over several generations. Unfortunately, when human intrusions are numerous, widespread, or intense, the relatively slow process of evolution just can’t catch up. If animals’ habitats are shrinking, they may have nowhere else to go to survive. Animals can’t move to cooler locations or elevations if they’re already at the peak of a mountain range or as far north as they can go. Animals can’t completely retool their sensory systems to avoid light or noise pollution.

“With every creature that vanishes, we lose a way of making sense of the world” (p. 348). All creatures in an ecosystem are interrelated, too, so if one or two disappear, the entire ecosystem is affected. For instance, humans are using noisy compressors to extract natural gas within the woodlands of New Mexico, driving off the Woodhouse’s scrub-jay who lives there. A single scrub-jay consumes and spreads about 3,000–4,000 pinyon-pine seeds every year. Each pinyon pine is vital to the forest ecosystem, providing both food and shelter for countless other species, including animals, fungi, and more. Pinyon pines grow very slowly, so the impact of noisy gas extraction can affect the ecosystem for many decades.

On the other side of the world, a devastating heat wave caused algae to flee from their symbiotic coral partners, leaving the corals to starve and bleach. Without the coral, the crustaceans and fish that relied on the coral were evicted. Steps can be taken to remediate the reefs that haven’t been completely destroyed, as well as to reduce the climbing temperatures. In an instant, we can reduce both noise and light pollution. The COVID-19 lockdown taught us that ecosystems can revive and thrive when humans reduce our activities.

Each of us can do our part to affect our corner of the world, through our own individual actions. We can dim or turn off outdoor lights, or shield them to face downward, or change the color from white or blue to red or yellow. We can minimize our plastic waste and maximize our efforts to reduce, reuse, recycle, and repair.

Another “R” is to “rot” — that is, to compost your food waste. Though we all try to minimize wasted food, what about those coffee grounds, banana peels, cherry seeds, and so on? San Diego, California, and many other locales make it easy to compost, but if your locale doesn’t offer it, you can make your own compost in your back yard (or give it to a pal who has a garden).

Figure 08. My compost bin runneth over after I’ve squeezed the juice of a dozen lemons to be frozen in ice-cube trays. Beneath the lemon peels are coffee grounds and various fruit seeds and peels. Between trips to dump out the contents, the bin is covered with a special lid that theoretically filters out fruit flies while allowing in air. That’s the theory. The contents sometimes look bad, but they rarely smell bad, and odors never escape through the lid.

These individual actions are vital and make a big difference within a community. The greatest impact, however, has to come through societal actions, legislation, policies. As much as you can, help with advocacy for making big societal changes: Contact community, local, state, and national leaders yourself. Pitch in to help organizations advocate on your behalf.

Find ways to help others to enjoy and appreciate the natural world. Help maintain your local parks, beaches, and other places where people can sense the joys of being in touch with nature and our natural world. Festoon your yard with native plants that require minimal intervention to appeal to humans, birds, small mammals and reptiles, insects. “To perceive the world through other senses is to find splendor in familiarity, and the sacred in the mundane. Wonders exist in a backyard garden. . . . Wilderness is not distant” (p. 353).

One woman’s opinion: When I volunteered at our local zoo, my main reason for being there was to help people of all ages to enjoy and appreciate the animals and plants there. We protect whom and what we love. — SDH

“Through patient observation, . . . , through the scientific method, and . . . through our curiosity and imagination, we can try to step into [the Umwelt of other animals]. We must choose to do so” (p. 353).

[back matter], 357–453

- Acknowledgments, 357–359, starting with an appreciation of his wife, Yong warmly acknowledges those who helped him produce this book.

- Notes, 361–384, references are sorted by chapter and indicated by page number, with a tag line linking it to the text; citations are listed in the bibliography; easy to use

- Bibliography, 385–429, comprehensive, alphabetical, including the citations from the notes section

- Insert Photo Credits, 431–432, acknowledging the sources for more than 60 exquisite and delightful full-color photos on 32 full pages of photo inserts.

- Index, 433–449, very thorough and well organized — as usual, I still added my own index items, such as auklet (whiskered), barn owl, Bactrian camel, muscle contractions subheading for bats on the first page of the index

- [about the author, 451 — photo and paragraph about the author, as well as contacts for speaker requests]

- [about the type, 453 — if you’re a

bibliophile,bibliomaniac, you’ll enjoy reading this]

Copyright, 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch, images and text, except where specific attributions are noted. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to sdh51445e9c228f Cancel reply