Figure 00. This Spotted Sandpiper used vision to catch this tiny crab, but it’s also using its sense of touch to get the crab into its throat, to swallow.

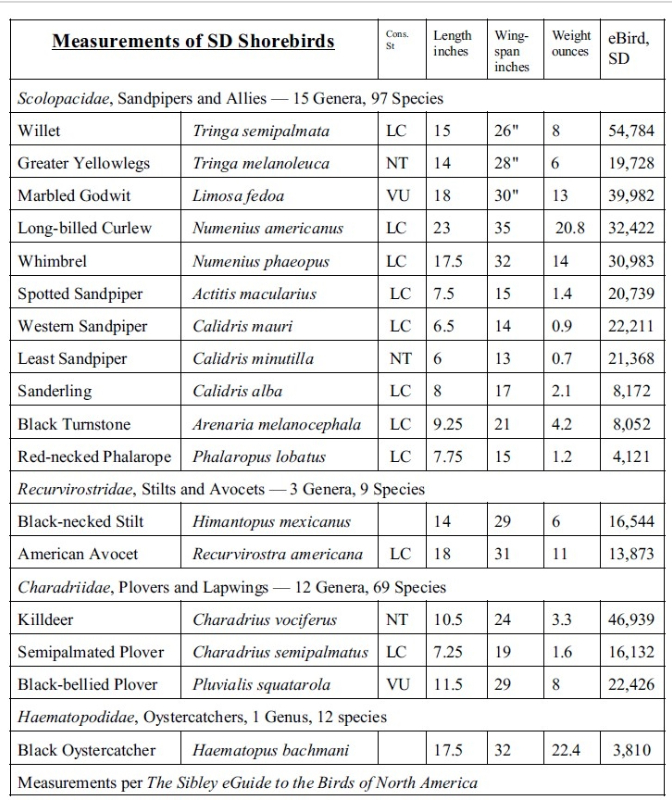

San Diego, California, regularly hosts more than 30 species of shorebirds, at least some of whom stay here year-round. Many shorebirds use a keen sense of touch, as well as vision and sometimes smell and taste, to survive and to thrive. (A table of the most common San Diego shorebirds and their approximate measurements appears at the end. Resources used for this article can also be found at the end.)

The sense of touch encompasses multiple sensations: pressure (continuous, what we think of as “touch”), vibration, temperature, muscle tension, internal movements of joints, and pain (various kinds of pain in internal organs and in skin). Touch sensations haven’t been well studied, so there may be others, too. For instance, birds can sense fluctuations in barometric pressure (the pressure of air, which changes at different elevations, times of day, and locations). When air pressure is higher, air is denser, and flying is easier; the inverse happens with low barometric pressure.

Figure 01. Birds can sense barometric (air) pressure; when air is denser, birds such as these sandpipers and gulls can fly more easily.

Because of the variety of touch sensations, birds’ touch-sensation receptors can be found in many locations: muscles, joints, internal organs, legs, toes, skin, tongue, palate, and bill. Pain can be sensed through receptors internally, in the skin, and in and around the bird’s bill and mouth.

Figure 02. The inside of a bird’s mouth and bill — such as this Brown Pelican’s — is highly enriched with numerous touch receptors of various kinds.

For flighted birds, the most important touch receptors are in the skin attached to feathers. Probably the most important of these receptors occur where the skin attaches to specialized filoplumes (willowy bare quills with fluffy tufts at the tips). Filoplumes lack the vanes found on most other feathers, and most of their length (the rachis) is completely bare. The top, however, has a fluffy tuft, which air can move easily.

Figure 03. This illustration of a goose filoplume, by F.W. Headley (1895), is in the public domain, having originally appeared in his The Structure and Life of Birds, London: Macmillan, p. 145.

Typically, each filoplume pairs closely with a contour (flight) feather. The skin at the base of each filoplume senses the feathers’ movements. If any feather is amiss, the bird can make some adjustments, even while in flight. Filoplumes also help guide birds’ preening, sensing when feathers aren’t perfectly aligned. In addition, filoplumes may enhance how allopreening (birds preening each other) is felt and appreciated by the bird being preened.

Figure 04 (a,b). Inside Willets’ skin, touch receptors sense information from filoplumes, which pair with the contour feathers; these touch sensations guide the Willet in knowing which feathers need to be better aligned during preening.

Unfeathered skin also has sensory receptors, such as in response to pain, pressure, and temperature. Temperature sensors play a key role in breeding behavior for many birds. Typically, one or both parents develop one or more brood patches — bare areas of skin on the belly, where the bird’s skin contacts the eggs or hatchlings. Brood patches are highly sensitive to temperature and can help parent birds ensure that their eggs are warm enough in cool weather yet cool enough in warm weather. (Actually, some overheating can be more dangerous than some chilling.) Birds who breed in warm locations can sense potential overheating and can decrease blood flow to the brood patch, so they can draw heat away from their eggs. Killdeer, stilts, avocets, and many other birds will also soak their belly feathers then return to the nest to cool off their overheated eggs.

Figure 05. Even megapode mound-builders use temperature sensations when breeding. Rather than brooding their eggs through contact with their bodies, they build mounds into which their eggs are laid. Nonetheless, these parents carefully regulate the temperature inside the mounds by poking their heads into the mound and taking its temperature with their tongues and palates, then they adjust the temperature, as needed, by adding or removing materials to or from the mound. This photo of an Australian Brush turkey on its mound at the Kansas City Zoo, by D. Cowell (5 December 2007), is published here, with permission, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brushturkeykansaszoo.jpg.

Deeper in the bare skin of many birds are more tactile receptors, which respond to pressure, acceleration, and vibration. Wing tips and joints may also sense vibrations due to air currents. The long legs of many waders (e.g., herons) can detect vibrations in water. Many shorebirds can sense vibrations within mud or wet sand, through their toes. When plovers jiggle wet mud or sand, they are trying to see prey movements, but they may also notice vibrations through their feet.

Figure 06. Plovers — such as this Killdeer — sometimes jiggle their feet to stir prey to move around, so they can spot them visually, but it’s not impossible that they’re also sensing prey movements through their feet.

Shorebirds have to adapt their feeding schedule to align with changes in the tides, so it’s an advantage to be able to detect prey tactilely, not just visually. Through tactile foraging, they can feed in dim light or near-darkness. For many shorebirds and other birds, the tips of their bills are densely packed with tactile sensors, to differentiate potential food from non-food (e.g., mud, sand, pebbles). When the shorebird probes into the mud or sand, these tactile sensors can detect pressure, movement, or vibration, created by their invertebrate prey.

Figure 07. These shorebirds — Long-billed Curlew, Marbled Godwits, Willet — can use both visual and tactile strategies for finding prey, which makes them better adapted to foraging in whatever light is available when the tides are best suited for catching their prey.

Birds’ bills are made of a lightweight, somewhat flexible rhamphotheca (made of keratin, like your fingernails). Inside the bill, lightweight bony struts reinforce the jaws, and flexible joints open and close the bill. In addition, some shorebirds (curlews, godwits, dowitchers, et al.) have flexible joints farther down their upper mandibles (top half of the bill). These joints let them flexibly open or close just the tips of their bills, using rhynchokinesis. Thus, shorebirds can probe with their touch-sensitive bill tips slightly ajar, then they can reflexively snap their bills around prey the instant it’s detected (the way you can reflexively pull your hand away from a fiery skillet).

Figure 08. Many shorebirds, such as this Long-billed Curlew, can readily manipulate their long bills in multiple ways. (Shown here with slightly slowed motion.)

Numerous shorebirds use both visual and tactile strategies for catching prey. During the day and on brightly moonlit nights, Willets mostly forage by looking for crabs and other invertebrates to snatch. On dark, moonless nights, however, they switch to probing for prey, detecting it tactilely. In practice, they may use both tactile and visual methods when foraging during daytime. Greater Yellowlegs have good diurnal (daytime) vision, so they forage visually, stabbing at prey on the water surface. With their poor nocturnal vision, however, at night, they switch to side-sweeping motions and catch prey by touch. Marbled Godwits, Black-necked Stilts, and American Avocets also use visual feeding strategies some of the time (e.g., plucking prey from the water or mud) and tactile strategies at other times (e.g., probing in the mud or water and sensing prey with the bill).

Figure 09. American Avocets, like Marbled Godwits and Black-necked Stilts, use visual foraging strategies sometimes and tactile strategies at other times.

Other shorebirds rely more on tactile searches for prey. For instance, Long-billed Curlews, which can probe much more deeply than most other shorebirds, can sense and catch prey (shrimp, crabs, worms) hiding in burrows deep below the surface. Once a curlew detects prey, it instantly closes its mandibles, jerks its head back to raise its bill out of the muck, and moves the prey toward its mouth, for swallowing.

Western Sandpipers and Least Sandpipers have mechanoreceptors — specialized touch sensors — in their bills, especially at the tips, which can detect buried invertebrate prey. Least Sandpipers can peck more quickly than other sandpipers, making multiple pecks to find and extract prey hiding in burrows. Western Sandpipers peck, but they also probe and “flutter-feed” using water’s surface tension to draw food to them. They also “graze,” using their bristle-sided tongues to scrape biofilm (a thin coating of microorganisms) from the surface of the sediment.

Figure 10. Western Sandpipers use various strategies for foraging, chiefly taking advantage of the sensitive mechanoreceptors — touch sensors — in their bills, which instantly sense contact with prey.

Another interesting shorebird is the Sanderling, which uses multiple senses to hunt for prey. It runs along the shore, skipping ahead of waves, catching invertebrate prey as the waves recede. Visually, it snatches prey seen on the sand and snaps at insects seen in the air. By touch, using its sturdy, sensitive bill, it probes and digs into wet sand or mud, finding burrowed prey. It also uses taste to sense prey in wet sand or mud, using chemical taste receptors at the back of its mouth.

Figure 11 (a,b). Sanderlings ably forage for prey visually, grabbing prey from the sand or midair, but they can also forage tactilely, sensing where to find burrowed prey, and even using taste to sense where prey may be located in wet sand or mud.

Inside most birds’ bills, the tongue is packed with tactile sensors. In Western Sandpipers, sensors in the tongue help them graze biofilm. For other birds, these sensors still play a vital role. Touch sensors in the tongue not only differentiate food from non-food, but also help to position the food for maneuvering, handling, and swallowing. Even visual foragers, such as Whimbrels, plovers, Spotted Sandpipers, Black Turnstones, and Black Oystercatchers, rely on touch sensors in the bill, mouth, and tongue to manipulate food for swallowing.

Figure 12. Even shorebirds who forage visually, such as this Whimbrel, must use touch sensors in their bill, mouth, and tongue to manipulate food to swallow it.

The preceding table includes measurements gained from the Sibley eGuide to the Birds of North America cellphone app; the eBird observations were reported in San Diego, California, as of May 3, 2025.

Text by Shari Dorantes Hatch; except where indicated, images are by Shari Dorantes Hatch.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

I welcome your comments, suggestions for improvement, tips, or ideas. I look forward to hearing from you.

Resources

Books

- Elphick, Chris, John B. Dunning, Jr, & David Allen Sibley. (2001). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. (Illustrated by David Allen Sibley).

- Elphick, Jonathan. (2016). Birds: A Complete Guide to Their Biology and Behavior. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books.

- Kricher, John. (2020). Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Lovette, Irby, & John Fitzpatrick (eds.), (2016). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology Handbook of Bird Biology (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Morrison, Michael L., Amanda D. Rodewald, Gary Voelker, Melanie R. Colón, Jonathan F. Prather (Eds.). (2018). Ornithology: Foundation, Analysis, and Application. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Stokes, Donald W., and Lillian. (1983). A Guide to Bird Behavior, Volume II: In the Wild and at Your Feeder. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. Vol. 2. Stokes Illustrated by John Sill, Deborah Prince, and Donald Stokes.

- ○ Killdeer, pp. 23–35

- ○ Spotted Sandpiper, pp. 37–47

Birds of the World (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, online subscription)

- Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae) — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Oystercatchers (Haematopodidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.haemat1.01. 1 Genera, 12 Species

- Black Oystercatcher, Haematopus bachmani — Brad A. Andres and Gary A. Falxa, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 1995

- Plovers and Lapwings (Charadriidae) — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Plovers and Lapwings (Charadriidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.charad1.01. 12 Genera, 69 Species

- Killdeer, Charadrius vociferus — Bette J. Jackson and Jerome A. Jackson, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 2000

- Semipalmated Plover, Charadrius semipalmatus — Erica Nol and Michele S. Blanken, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated September 9, 2014

- Black-bellied Plover, Pluvialis squatarola — Alan F. Poole, Peter Pyle, Michael A. Patten, and Dennis R. Paulson, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

- Sandpipers and Allies (Scolopacidae) — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Sandpipers and Allies (Scolopacidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.scolop2.01 15 Genera, 97 Species

- Willet, Tringa semipalmata — Lowther, P. E., H. D. Douglas III, and C. L. Gratto-Trevor (2020). Willet (Tringa semipalmata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.willet1.01

- Greater Yellowlegs, Tringa melanoleuca — Elphick, C. S. and T. L. Tibbitts (2020). Greater Yellowlegs (Tringa melanoleuca), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.greyel.01

- Marbled Godwit, Limosa fedoa — Gratto-Trevor, C. L. (2020). Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.margod.01

- Long-billed Curlew, Numenius americanus — Dugger, B. D. and K. M. Dugger (2020). Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.lobcur.01

- Whimbrel, Numenius phaeopus — Skeel, M. A. and E. P. Mallory (2020). Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.whimbr.01

- Spotted Sandpiper, Actitis macularius — J. Michael Reed, Lewis W. Oring, and Elizabeth M. Gray, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 30, 2013

- Western Sandpiper, Calidris mauri — Samantha E. Franks, David B. Lank, and W. Herbert Wilson Jr., Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 31, 2014

- Least Sandpiper, Calidris minutilla — Silke Nebel and John M. Cooper, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated September 9, 2008

- Sanderling, Calidris alba — R. Bruce Macwhirter, Peter Austin-Smith Jr., and Donald E. Kroodsma, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 2002

- Black Turnstone, Arenaria melanocephala — Colleen M. Handel and Robert E. Gill, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 2001

- Red-necked Phalarope, Phalaropus lobatus — Margaret A. Rubega, Douglas Schamel, and Diane M. Tracy, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020

- Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae) — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Stilts and Avocets (Recurvirostridae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.recurv1.01 — 3 Genera, 9 Species

- Black-necked Stilt, Himantopus mexicanus — Julie A. Robinson, J. Michael Reed, Joseph P. Skorupa, and Lewis W. Oring, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 1, 1999

- American Avocet, Recurvirostra americana — Joshua T. Ackerman, C. Alex Hartman, Mark P. Herzog, John Y. Takekawa, Julie A. Robinson, Lewis W. Oring, Joseph P. Skorupa, and Ruth Boettcher, Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020, Text last updated January 3, 2013

Wikipedia

- Sense or touch, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Somatosensory_system

- tactile sensation cells in the skin, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merkel_cell

- tactile-pressure sensations in the skin, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tactile_corpuscle

- vibration sensors in the skin, joints, and internal organs, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pacinian_corpuscle

- sense continuous pressure deep in the skin and joints, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bulbous_corpuscle

- Proprioception of the body’s movements and positions, through sensory receptors in the muscles, tendons, and joints, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proprioception

- Vestibular senses, equilibrium, and balance, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sense_of_balance#Vestibular_system

Other Resources

- Breuner, Creagh Rachel Seabury Sprague, Stephen H Patterson, H Arthur Woods. “Environment, behavior and physiology: Do birds use barometric pressure to predict storms?” Journal of Experimental Biology 216(Pt 11):1982–1990, June 2013. DOI:10.1242/jeb.081067, PubMed. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236912744_Environment_behavior_and_physiology_Do_birds_use_barometric_pressure_to_predict_storms

- Lederer, Roger “Can Birds Predict the Weather?” Ornithology: The Science of Birds, January 8, 2023. https://ornithology.com/can-birds-predict-the-weather/

- Renaud, Jeff. “Birds predict weather change and adjust behaviour by reading barometric pressure,” (2013, November 20; retrieved 13 May 2025 from https://phys.org/news/2013-11-birds-weather-adjust-behaviour-barometric.html. Animal Behaviour.

Leave a reply to Sensational Shorebirds of San Diego – Bird Brain Cancel reply