Black-spotted Barbet

(not local to North America)

Figure 01. Black-spotted Barbets share the Capitonidae family with toucans, but their bills are smaller, even relative to their diminutive body size. Barbets (and toucans) also share the Piciformes order with woodpeckers, but they aren’t as well equipped for piercing tough tree bark.

- Piciformes

- Description

- Diet and Foraging

- Breeding

- Capitonidae

- Distribution and Habitat

- Description

- Diet and Foraging

- Breeding

- Black-spotted Barbet, Capito niger

- Distribution and Habitat

- Description

- Diet and Foraging

- Breeding

- Conservation Status

- Resources

- Order: Piciformes

- Family: Capitonidae

- Species: Black-spotted Barbet, Capito niger

- General References

- Etymology

- Generation Length

Figure 02. The Black-spotted Barbet female (left) shows the namesake black spots on her breast, as well as more cryptic plumage overall, whereas the male’s white breast and black back and wings stand out.

Scientists group animals into a hierarchy, to more easily see which ones are more closely related to each other. Here’s the hierarchy for the Black-Spotted Barbet, starting with the animal kingdom:

- kingdom Animalia

- phylum Chordata

- class Aves (all living birds; includes ≈45 orders of birds; >10,000 species!!)

- order Piciformes (9 families, 71 genera, >450 species)

- family Capitonidae (15 species, 2 genera)

- genus Capito (11 species)

- species niger

- genus Capito (11 species)

- family Capitonidae (15 species, 2 genera)

- order Piciformes (9 families, 71 genera, >450 species)

- class Aves (all living birds; includes ≈45 orders of birds; >10,000 species!!)

- phylum Chordata

Piciformes

Piciformes includes 9 families of mostly tree-hugging birds: Capitonidae (New World barbets), Lybiidae (African barbets), Megalaimidae (Asian barbets), Ramphastidae (toucans), Bucconidae (puffbirds), Galbulidae (jacamars), Semnornithidae (toucan-barbets), Indicatoridae (honeyguides), and Picidae (woodpeckers).

Figure 03. San Diegans can often see Acorn Woodpeckers (top) and Nuttall’s Woodpeckers (bottom) living in inland forests, and occasionally, these Picidae (woodpeckers) also visit the coast.

Picidae (picus, “woodpecker,” Latin, from Greek), the best-known Piciformes family, comprises 240 species (35 genera), about half of the 450 Piciformes species (71 genera). For a sampling of the myriad fascinating Picidae species, please see https://wp.me/pnSyw-tNQ, by “Wickersham’s Conscience” (aka Hieronymous Bosch on Facebook, aka Jim DeWitt offline). If you have access to Facebook, I also recommend Joe Galkowski’s post about Acorn Woodpeckers, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid0AJ4Czv9R6EyyM6dCnSaY1gubjR6HiU2ZPAHqJCbMND8PN6kMCrW2CAc8uP9jiLJYl&id=100009579312079&mibextid=N5oz

Description

The vast majority of Piciformes have no down feathers, even just after hatching. Almost all have zygodactyl toes, two pointing forward, two pointing back. Zygodactyl toes make it easier to climb and move around on tree trunks, where they spend most of their time. They range widely in size, from the 3″, 0.25-ounce Rufous Piculet, to the male Toco Toucan, 22″ long, 28 ounces. (Imagine a scale with 112 piculets on one side and 1 male toucan on the other.)

Figure 04. Having zygodactyl toes (two forward-, two backward-facing) makes it easier for Piciformes species not only to grasp branches but also to move easily up and down on tree trunks.

Diet and Foraging

Most Piciformes eat insects (especially larvae), but barbets and toucans eat mostly fruit; honeyguides are the only living birds that can digest beeswax, in addition to eating insects.

Breeding

All Piciformes nest in cavities, and all hatchlings are helpless, dependent on their parents.

Capitonidae

The Capitonidae family includes just 15 species of New World barbets, who live in the Americas. Capito (“head,” Latin) refers to their relatively large heads, accented by thick heavy bills.

Distribution and Habitat

New World barbets live mostly in humid lowland forests in neotropical Central and South America, though some range into temperate and even montane cloud forests. Barbets prefer to nest in trees with dead wood, which they can easily excavate for nest cavities. Capitonids don’t migrate.

Description

Capitonid plumage shows an array of green, red, yellow, white, or black plumes, with bold contrasting patches of color. A few short rictal bristles (stiff, hair-like feathers) adorn the base of the bill. Most have big heads, short necks, and plump bodies. Their vocalizations are rhythmic, husky, whistly notes.

Figure 05. Similar to New World Barbets, Asian Barbets such as this Fire-tufted Barbet (left; Megalaimidae) have vividly colorful plumage, and African Barbets such as this Bearded Barbet (right; Lybiidae) have prominent rictal bristles.

Diet and Foraging

Capitonids eat mostly fruits, but their diets also include many arthropods (e.g., insects, scorpions, spiders), as well as some small vertebrates (e.g., frogs), especially when nesting. They mostly hang out high up in trees, harvesting clusters of fruits and gleaning insects from dead leaves, trunks, or branches. They adapt their diet to suit food availability, eating cultivated fruits and vegetables when handy. They eat whole fruits then later regurgitate any indigestible pits or seeds, thereby dispersing fruit seeds.

Breeding

Barbet parents are monogamous. Part of their courtship involves digging out nest cavities together, while the male feeds the female. The female lays 2–5 eggs, which both parents incubate for about 2 weeks. Both parents tend to their chicks for 4–6 weeks until the chicks fledge.

Figure 06. During the courtship of these monogamous birds, the barbet male (with the all-white breast) often feeds the female (with the black spots on her breast), but apparently this Black-spotted Barbet male didn’t get the memo.

Black-spotted Barbet, Capito niger

Distribution and Habitat

The Black-spotted Barbet lives in diverse woodlands, from sea level to 2,600 feet, in northeastern South America. They inhabit the canopy of forest edges, orchards, palm groves, elfin forests, lowland forests, and riparian woodlands.

Description

Niger (“black,” Latin) refers to the male’s black back, sides, and tail. Both sexes have a striking red throat and forehead. The name “Black-spotted” seems to apply more to the female than to the male. Both are small (less than 2 ounces, 7″ long), with a bill almost 1″ long. (Proportionately, if this barbet were the length of a 6′ tall human, its bill would be 10″ long.)

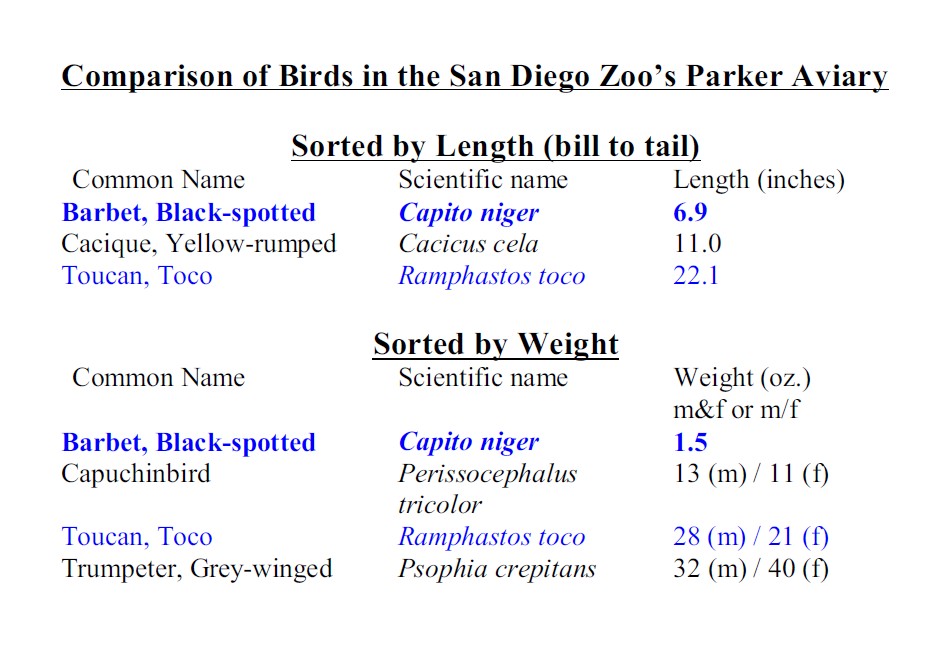

Figure 07. In the Parker Aviary of the San Diego Zoo, Black-spotted Barbets are shorter (from bill to tail) and lighter (weight) than the other birds there. (Note. This list is abbreviated.)

Diet and Foraging

This bird’s diet and foraging are probably like other capitonids: mostly fruit, some insects, occasionally small vertebrates.

Figure 08. Black-spotted Barbets eat opportunistically, mostly fruits, but also insects or other food they can grasp easily.

Breeding

Males engage in some courtship displays, accompanied by vocalizations — see https://xeno-canto.org/species/Capito-niger. Both parents dig an 8–12″ deep cavity about 16–39 feet up in a tree, leaving an entrance hole smaller than 2″. The female lays 3–4 white eggs, which both parents incubate. (Length of incubation isn’t known.) Both parents feed their hatchlings, which fledge about 34 days after hatching. The chicks continue to be fed by both parents for another 3 weeks or so before leaving the nest. Age of sexual maturity, about 1.4 years.

Conservation Status

IUCN Red List status is LC, Least Concern; global population isn’t known, but it probably has a stable population trend; no known threats limit its large population in its range. No longevity data are available for this species, but a closely related species, the Gilded Barbet (Capito auratus), has a maximum recorded age of 11.3 years in managed care; IUCN generation length is about 8.5 years.

Figure 09. Luckily, Black-spotted Barbets belong to a species with a stable population and no known threats to their well-being.

Resources

Order: Piciformes

- Elphick, Jonathan. (2014). The World of Birds. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. (Pp. 434–439)

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, & Irby J. Lovette. (2015). Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- pp. 233, 239, 240–241, Piciformes

- https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species, “Orders and Families,” 11,017 species

- African Barbets (Lybiidae) — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, & I. J. Lovette (2020). African Barbets (Lybiidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, & T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.lybiid1.01

- Asian Barbets Megalaimidae — Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, & I. J. Lovette (2020). Asian Barbets (Megalaimidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, & T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.megala2.01

Family: Capitonidae

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, & I. J. Lovette (2020). New World Barbets (Capitonidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, & T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.capito2.01

- Gilded Barbet, Capito auratus

Species: Black-spotted Barbet, Capito niger

- Short, L. L., J. F. M. Horne, G. M. Kirwan, & C. J. Sharpe (2020). Black-spotted Barbet (Capito niger), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, & E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blsbar1.01

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=59156D530947AC82&sec=lifehistory

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22733719/95063122

- https://xeno-canto.org/species/Capito-niger

General References

- Elphick, Jonathan. (2014). The World of Birds. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books.

- pp. 32–35, feet and toes

- Lovette, Irby, & John Fitzpatrick (eds.), (2016). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology Handbook of Bird Biology (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- p. 178–183, skeleton, feet, toes, dactyly

- p. 274–286, foraging, diet

- pp. 43–59, bird orders and families

- Morrison, Michael, Amanda Rodewald, Gary Voelker, Melanie Colón, & Jonathan Prather (eds.), (2018). Ornithology: Foundation, Analysis, and Application. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

- p. 147, dactyly, toes

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, & Irby J. Lovette. (2015). Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Etymology

- Gotch, Arthur Frederick. (1980). Birds—Their Latin Names Explained. Dorset, UK: Blandford Press.

- Gruson, Edward S. (1972). Words for Birds: A Lexicon of North American Birds with Biographical Notes. New York: Quadrangle Books. 305 pp., including Bibliography (279–282), Index of Common Names (283–291), Index of Generic Names (292–295), Index of Scientific Species Names (296–303), Index of People for Whom Birds Are Named (304–305).

- Lederer, Roger & Carol Burr. (2014). Latin for Bird Lovers: Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained. Portland: Timber.

Generation Length

Copyright, text and images, 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

Note. If you have suggestions for improvements, tips for this blog, ideas for future blogs, or any other comments, I would be delighted to hear from you. Thank you.

Leave a comment