Inca Tern

- Charadriiformes

- Laridae

- Diet and Foraging

- Terns

- Gulls

- Skimmers

- Breeding

- Diet and Foraging

- Laridae

- Inca Tern, Larosterna inca

- Distribution and Habitat

- Description

- Diet and Foraging

- Breeding

- Conservation Status

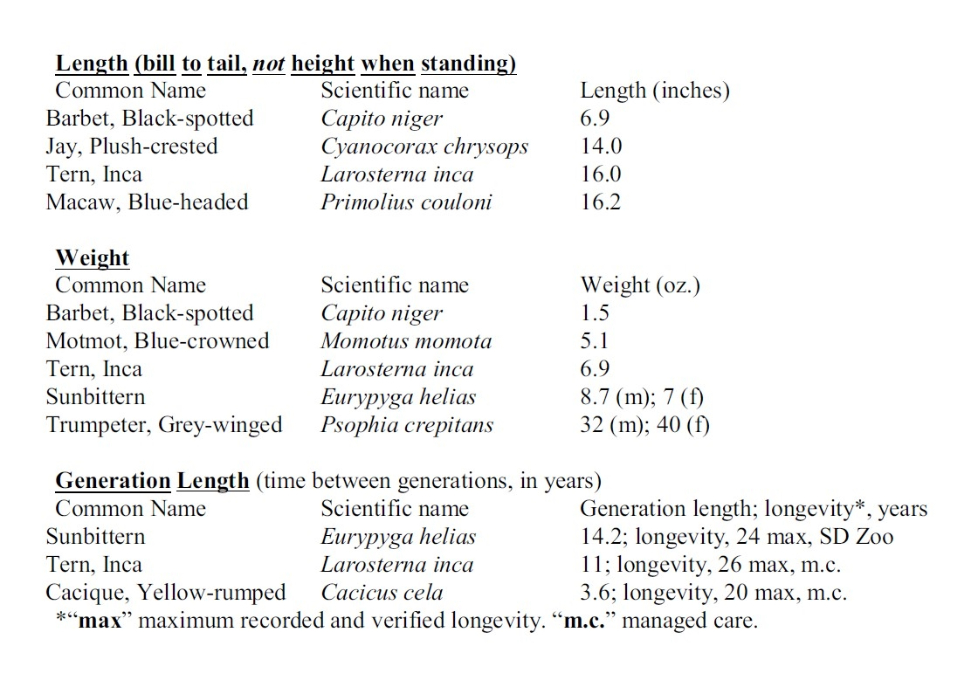

- Inca Tern, compared with other birds in the Parker Aviary

- Resources

Figure 01. Inca Terns are highly sociable, faithful partners, and devoted parents.

Scientists group animals into a hierarchy, to more easily see which ones are more closely related to each other. Here’s the hierarchy for Inca Terns, starting with the animal kingdom:

- kingdom Animalia

- phylum Chordata

- class Aves (all living birds; includes ≈45 orders of birds; >10,000 species!!)

- order Charadriiformes (19 families, ≈390 species)

- family Laridae (≈100 species)

- genus Larosterna (1 species)

- species inca

- genus Larosterna (1 species)

- family Laridae (≈100 species)

- order Charadriiformes (19 families, ≈390 species)

- class Aves (all living birds; includes ≈45 orders of birds; >10,000 species!!)

- phylum Chordata

Charadriiformes

Charadriiformes can be found wherever there’s water, throughout the world (even Antarctica!).

Laridae

Larus means “ravenous seabird” (Latin; probably came from Greek laros, which Aristotle probably used to describe a gull). The Laridae family comprises 100 species of larids — gulls, terns, skimmers, noddies, and kittiwakes, which fly worldwide in search of prey (mostly fish or aquatic invertebrates). Most larids hug the coasts, but some are pelagic (staying at sea most of the year), and some live pretty far inland, commuting to fish each day. A wider diversity of terns and skimmers live in the tropics, and a greater variety of gulls can be found in temperate zones. Many larids have adapted to living side by side with humans.

Figure 02. Inca Terns don’t resemble any other larids, not even the other terns in the Laridae family. The Inca Tern is the only member of the Larosterna genus.

These predators can vary widely in size:

- small — Least Tern, 9″ (≈22 cm), 1.6 ounces (≈44 g), smallest tern in North America

- medium — Caspian Tern, 21.5″ (≈50 cm), 24–28 ounces (≈650 g), largest tern in the world

- biggish — Western Gull, 24″ (63 cm), 28–46 oz. (≈1000 g), larger than other gulls in San Diego area

The three basic types of larids are terns, gulls, and skimmers; each type has a distinctive style of getting food.

Diet and Foraging

Terns

Terns eat mostly live fish and aquatic invertebrates; they spy prey from above, then plunge-dive to catch it.

Gulls

Gulls use almost any means to devour fish, mammals, birds, crustaceans, insects, and pretty much any living or dead animal they can swallow. Most are known scoundrels, too, stealing food. (The polite name is “opportunistic kleptoparasites.”)

Skimmers

Skimmers eat small fish or crustaceans; a skimmer catches prey by skimming its elongated lower bill across the surface of calm water, then snapping its bill shut as soon as it senses prey touching its bill.

Figure 03. Black Skimmers skim their lower mandible (jaw) along the surface of the water, hoping to detect a fish or other prey. As soon as they do, their jaw snaps shut, snatching it.

Breeding

Larids nest in a wide array of locations (cliff ledges, trees, sandy beaches). They don’t go to a lot of trouble to make their nests — perhaps a loose assortment of twigs and feathers, or even just a scrape on the sand suffices.

Both larid parents are monogamous, and both help to incubate the eggs (for about 19–40 days) and to care for their hatchlings. Their chicks are precocial (feathered when they hatch) and can thermoregulate (control their own body temperature) soon after hatching. Even so, they still need to have their parents feed them until they’re ready to leave the nest, about 4–6 weeks after hatching.

Figure 4. Like other larids, Western Gull chicks receive food and other care from both parents for a few weeks after hatching. The chicks hatch with downy feathers, which switch out to flight-ready feathers within weeks.

To provide better protection from potential predators, most larid species nest in colonies or at least near others of their species, often in crowded groupings. If parents detect a predator, they aggressively call the alarm, then dive-bomb, poop on, and attack the potential threat.

Figure 05. Like other larids, Inca Terns like hanging out together and chatting.

Inca Tern, Larosterna inca

The genus Larosterna = larus (“gull,” Latin) + sterna (“tern,” Dutch). The inca species name points to the Inca empire, former rulers of Larosterna inca’s habitat.

Distribution and Habitat

Inca Terns mostly stick to the rocky Pacific coast of South America from north-central Chile to Ecuador, but they sometimes hang out in Panama and Costa Rica. Typically, this tern doesn’t migrate far, but it will move to find food if not breeding. When nesting, it prefers rocky sea cliffs and guano-covered islands.

Description

The genus Larosterna includes only this species, and Inca Tern plumage differs from that of other terns. Most notably, males and females sport a stunning white handlebar mustache, accented by a bright yellow gape (mouth edges), deep red-orange bill (up to 2″ long), and brown eyes. It has striking crimson legs and webbed toes. Its size averages 16″, 6.8 ounces.

Figure 06. The brilliant colors, the startling contrasts, and the striking mustache on the head of an Inca Tern catch your eyes!

When hanging out with other Inca Terns, it does “raucous cackling” and “mews.” See https://xeno-canto.org/species/Larosterna-inca for examples.

Diet and Foraging

Though Inca Terns primarily eat small fish, they also scarf down small crustaceans and any scraps left by larger predators, such as whales, sea lions, cormorants. They opportunistically follow fishing boats, too. Like other terns, they typically catch prey by flying over water to spot prey, then plunge-diving to catch it. They also snatch potential food observed on the water surface, either from the air or when floating.

Breeding

Inca Tern parents choose a mate with a suitably long mustache, indicating health and fitness.

Figure 07. “WHOO-HOO! Honey, your moustache is so long!!!” “Thank you! Yours is strikingly long, too!” Both male and female Inca Terns find extra-long moustaches quite sexy!

Both parents are monogamous, incubate their eggs, and care for their young. Inca Terns aren’t fussy about when or where to breed: Almost any time of year, a rocky crevice, an abandoned burrow, or a gap between rocks or boulders can offer a chance for nesting. However, if the parents notice potential predators, they make more of an effort to hide the nest.

The female lays 1–2 eggs (tan or light brown with dark brown spots); observers haven’t detected how long the eggs are incubated, but the youngsters fledge about 4 weeks after they hatch. Sexual maturity may be 2–3 years of age.

Conservation Status

Figure 08. Sadly, the exquisite and exotic Inca Tern is considered a Near Threatened species, so steps must be taken to conserve it for future generations.

IUCN Red List status is NT, Near Threatened. Population estimate: 50,000 pairs, but up to about 150,000 individuals in some years; population trend: decreasing. Threats: habitat destruction and loss, fishing and harvesting of other food sources; invasive non-native species and diseases; climate-crisis temperature extremes. Oceanic climate conditions dramatically affect food availability, which affects population. Maximum recorded longevity, 26 years, under managed care (perhaps up to 14 years in the wild); IUCN generation length is about 11 years.

Inca Tern, compared with other birds in the Parker Aviary of the San Diego Zoo

Figure 09 (a, b). The Inca Tern is one of the longest birds in the Parker Aviary of the San Diego Zoo.

Resources

General References

- Lovette, Irby, & John Fitzpatrick (eds.), (2016). The Cornell Lab of Ornithology Handbook of Bird Biology (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- pp. 43–59, bird orders and families

- Morrison, Michael, Amanda Rodewald, Gary Voelker, Melanie Colón, & Jonathan Prather (eds.), (2018). Ornithology: Foundation, Analysis, and Application. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Order and Family Information

- Order: Charadriiformes

- Elphick, Jonathan. (2014). The World of Birds. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. (Pp. 352–375)

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, & Irby J. Lovette. (2015). Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- pp. 119, 149–151, Charadriidormes

- https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species, “Orders and Families,” 11,017 species

- Family: Laridae

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, & I. J. Lovette (2020). Gulls, Terns, and Skimmers (Laridae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, & T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.larida1.01

- Western Gull

Species-specific Information — Inca Tern, Larosterna inca

- Gochfeld, M., & J. Burger (2020). Inca Tern (Larosterna inca), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, & E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.incter1.01

- Velando, A., C. M. Lessells, & J. C. Márquez. (2001). “The Function of Female and Male Ornaments in the Inca Tern: Evidence for Links between Ornament Expression and Both Adult Condition and Reproductive Performance.” Journal of Avian Biology, 32(4) (Dec., 2001), pp. 311–318 (Published by Wiley)

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=FF6C3B9C8E71701B&sec=lifehistory

- https://genomics.senescence.info/species/entry.php?species=Larosterna_inca

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22694834/132576903

- https://xeno-canto.org/species/Larosterna-inca

- Additional resources

Generation Length

IUCN Red List Status

Longevity Data and Life Histories

Vocalizations

Etymology

- Gotch, Arthur Frederick. (1980). Birds—Their Latin Names Explained. Dorset, UK: Blandford Press.

- Gruson, Edward S. (1972). Words for Birds: A Lexicon of North American Birds with Biographical Notes. New York: Quadrangle Books. 305 pp., including Bibliography (279–282), Index of Common Names (283–291), Index of Generic Names (292–295), Index of Scientific Species Names (296–303), Index of People for Whom Birds Are Named (304–305).

- Lederer, Roger, & Carol Burr. (2014). Latin for Bird Lovers: Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained. Portland: Timber.

Note. If you have suggestions for improvements, tips for this blog, ideas for future blogs, or any other comments, I would be delighted to hear from you. Thank you.

Copyright 2025, Shari Dorantes, text and photos. All rights reserved.

Leave a reply to sdh51445e9c228f Cancel reply