Tinamidae

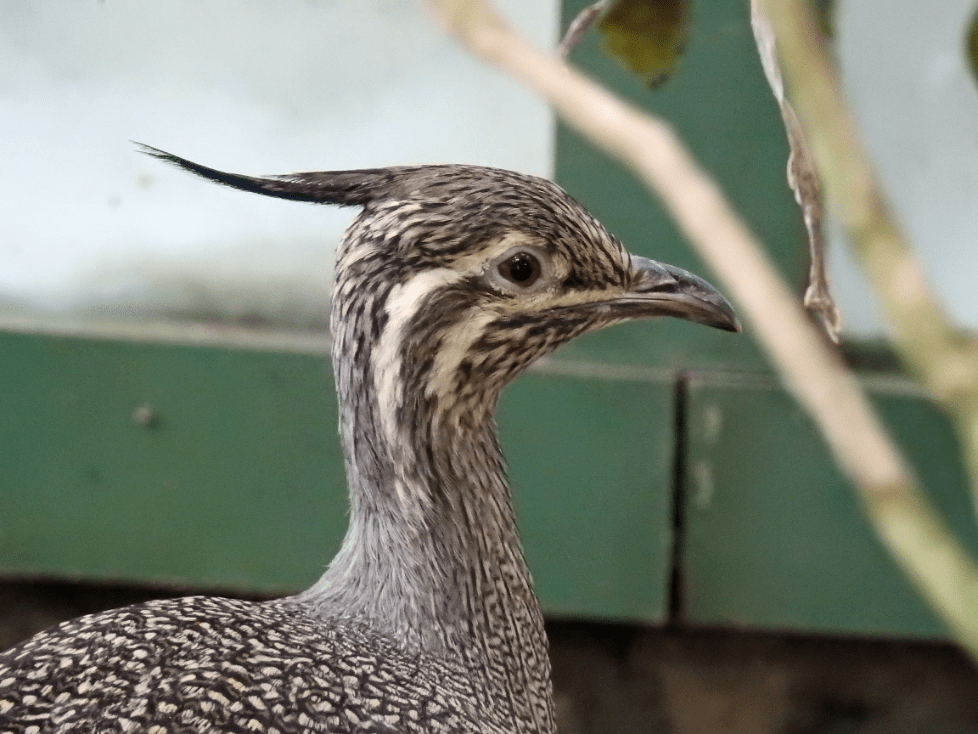

Tinamous aren’t vividly colorful, but in their own subtle way, they’re lovely birds, such as this Elegant Crested Tinamou, with its upswept crest, its downcurved bill, its cryptically patterned body plumage, and its white-striped facial adornment.

Currently, the Tinamidae family has its own bird order, Tinamiformes. At other times, the family has been subsumed under the Struthioniformes order, along with the flightless bird families: Struthionidae (ostriches), Casuaridae (emus and cassowaries), Rheidae (rheas), and Apterygidae (kiwis). Ornithologists continue to seek understanding of the relationships among birds. Among other revelations, such understanding may help to reveal whether the ability to fly emerged just once or emerged multiple times among different groups across evolutionary epochs.

Like the rheas, tinamous inhabit the Americas, from Mexico through Central and South America; tinamous mostly inhabit neotropical South America, especially Amazonia. Ground dwellers, tinamou species can live in a wide range of habitats — sea level to tall mountains (up to 16,000 feet / 5 m, or higher), dense humid rainforests to arid savannas. Universal, however, is that for all species, their habitats include at least some dense ground-cover, for easy camouflaged hiding.

Tinamous are plagued by bird lice, so they’re avid bathers. In wet habitats, they will wash themselves by standing erect, bill pointing upward, in a heavy downpour. In dryer habitats, they take dust baths, often frequently and vigorously enough to have their dust-covered feathers look like the surrounding soil. On occasion, tinamous also sunbathe, stretching out a wing while standing on one leg. Tinamous have dense feathers surrounding their cloaca, so to defecate, they must move those out of the way. In captivity, they defecate once/day; how often they do so in the wild isn’t known.

According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinamou, “tinamou” is the Galibi name for these birds.

(Galibi is the Cariban language of the Kalina, Carib, people of South America, spoken by about 7,400 people in the Guianas and neighboring countries; specifically, “tinamou” comes from French Guiana.)

Tinamidae includes 9 genera, divided across 46 (or 47) species of tinamous. They range widely in size: <6–21″ (15–53 cm) long, weighing between 1.5 ounces (Dwarf Tinamou) and close to 5 pounds (43–2300g; from lighter than a parakeet to heavier than a macaw). Their plump ovular bodies taper at each end — with slender medium-long necks and small heads at the top end, and short, downward-sloped tails at the other. Some tinamous have head crests. Their bills can be broad or slender, usually short but sometimes long, and most species have slightly decurved (downward) bills.

Their cryptic plumage is designed for camouflage, often mottled, spotted, streaked, or barred in neutral grays or browns. Tinamous also have well-developed powder-down feathers and small, tufted preen glands, for maintaining and waterproofing their feathers.

Figure 01. Tinamous are somewhat sexually dimorphic. Females tend to be a bit bigger and heavier than males, with brighter, paler, or more patterned plumage, and perhaps with legs of a different color than the legs of males. Might this difference relate to the sex difference in parenting roles? Only the males incubate and brood tinamou offspring.

Tinamous’ muscles weigh about 29–40% of their total body mass, comparable to the supermuscular hummingbirds, yet, as a proportion of their body weight, they have the smallest hearts and lungs of all birds — only 1.6–3.1% of their body weight. Not surprisingly, they have poor circulation, too. Though kin to the flightless ratites (ostriches to kiwis), tinamous do have (weak) flight muscles attached to the breastbone (sternum).

Their wings are short and rounded, so they have to lift a lot of body mass, in relation to the amount of wing surface area (called “high wing loading”). Taking flight is a major effort, involving lots of quick, noisy wingbeats to get into the air. Off the ground, they’re clumsy and will try to glide, with intermittent wing flaps. They have nearly no tail, so they can’t steer adequately and often crash into trees or other obstacles — sometimes fatally. For good reason, they’re among the most terrestrial of all flying birds. They’re reluctant to fly, unless they’re startled, with flight being the most obvious means of escape. Even then, they rarely fly more than 500 feet (150 m); they land upright, with head upstretched, perhaps at a run, on a downslope, if possible.

Figure 02. Not the most athletic of birds, tinamous have weak flight muscles, which enable them to fly — briefly, haltingly, and effortfully. They’re better suited to walking and can walk for long distances and even can run quickly, for short times, as needed.

In contrast to their weak flight muscles, they have short, strong, thick, scaly legs, with three forward-pointing toes. The fourth (hallux) rear-pointing toe is either elevated or missing altogether. They can still run quickly in bursts, but they soon tire and may stumble. A better defense from danger is their cryptic plumage — superlative camouflage. Their walk is silent, and if they detect a potential threat, they’ll either crouch or raise their head then freeze until they believe the threat has passed. If they can’t hide in dense vegetation, they’ll hide in burrows. Behaviorally, they’re wary, skulky, and secretive, more often and more readily heard than seen.

Tinamous may make an assortment of whistles, trills, rattles, and squeaks, such as those of the Elegant Crested Tinamou (available at https://xeno-canto.org/species/Eudromia-elegans); their whistles have been described as mournful, mellow, or flutey. They can vary in intensity, in frequency, and in variability, both across species and across individuals. For most species, both females and males call, but some calls are made by just one sex or the other. Observers have trouble locating the bird based on the vocalizations, as they can carry long distances. Though tinamous eat diurnally and roost at night, they may be heard calling morning, noon, and night. A calling tinamou will raise its neck, tilt its head, and open wide its bill.

Tinamou vocalizations increase during breeding season, and they appear to have a communicative function. The tinamou’s social behavior varies widely, with some species mostly solitary, some in year-round monogamous pairs, and some in social groups; some species are also seasonally more gregarious, and some social groups expand and contract seasonally.

At midday, tinamous rest or otherwise slow down, and when darkness falls, they rest all night in their roosts. Most species roost on the ground, but some forest species roost in low wide, thick branches of trees, which offer clear views and easy exits. If possible, they’ll approach a tree from uphill and fly down to the branch. On the branch, tinamous fold their legs beneath them, as they can’t grasp with their toes. Wherever they roost, they avoid defecating near the roost, to avoid notifying predators of their presence.

All tinamous are territorial, but that territory might be savannas and grasslands or forests. Both males and females will defend their territory, using feet and wings to attack a threat, but in some species, the females are more aggressive, whereas in others, the males are. Tinamous don’t migrate, though they will move a short distance during climatic extremes (e.g., floods, droughts).

As a family, tinamous are opportunistic and can be omnivorous, eating fruits, other plant matter, invertebrates, and sometimes small vertebrates. Three of the seven genera eat mostly fleshy fruits, three genera eat mostly seeds and soft plant matter (buds, shoots, flowers, etc.), and the genus living in high-altitude harsher environments eats almost all of each plant (e.g., also roots, tubers, and stems), not just the soft juicy bits.

Though some tinamou species are mostly herbivorous, most tinamous supplement their veggies with invertebrates — ants, termites, beetles, grasshoppers, insect larvae, other arthropods, snails, slugs, worms. Many species also eat small vertebrates (e.g., frogs, lizards, mice). If the vertebrates are too big to eat whole, they’ll beat the animal against the ground or even peck it apart. Seasonal availability affects diet, too. As opportunists, they focus on eating whichever food is more widely available. Also, growing chicks eat more insects than adults do.

Unlike most game birds (e.g., guineafowl, partridges), tinamous use their bills to probe into the soil (0.8–1.2″ / 2–3 cm down) or leaf litter in search of food, rather than scratching with their feet. Typically, they stroll with their heads down, pecking and poking; three species have nostrils at the base of their bills, to make deeper digging easier. Tinamous also poke open termite mounds in search of grubs. Some tinamous have been seen jumping off the ground (up to about 3 feet) to snatch leaves, buds, fruits, or insects. Some profit from associating with others while feeding, such as by hanging out with insectivorous birds or by following livestock. Livestock offer plenty of opportunities for finding insects: They host insects and other arthropods, which fall off; they brush insects off of bushes; and they stir insects up off the ground. Like most other birds, tinamous also ingest grit, which helps their gizzards mash up their food.

Some tinamou species live in arid or semi-arid environments, so they get most of their water from the foods they eat. Most, however, need to drink water; when they do, they can suck up the water and swallow it with their heads down, unlike most other birds, who need to lift their heads to swallow with a gravity assist.

Though some species of tinamous are monogamous, most aren’t. For most tinamous, both males and females have multiple mating partners within each breeding season, but how they go about it differs. Males establish a territory and vocally advertise their availability for breeding, often posturing, too; these males are simultaneously polygynous — mating with females who enter their territory. Females are sequentially polyandrous, responding to the advertisements of a sequence of males, wandering through their territories, and mating with them. For some tinamous, the “breeding season” is all year round, but for most tinamous, food availability fluctuates seasonally. For these tinamous, breeding season occurs when there is the greatest availability of food.

Males build the nests, incubate the eggs, and care for the chicks. Most dads don’t go to a lot of trouble building the nests, usually just a simple scrape of the ground or on leaf litter, or perhaps a few sticks and some grass; however, some males weave nests of grass. In any case, the dads do ensure that the nests are well hidden from view, obscured by dense vegetation or other natural barrier.

Figure 03, a,b. These tinamou eggs (a. Tinamus guttatus; b. Nothura maculosa) were photographed by Marcos Massarioli. Through Wikimedia, permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation. You are free: to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work, to adapt the work, under the following conditions: You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

All tinamou moms lay beautiful, glossy one-color unpatterned spherical or elliptical eggs; the particular colors vary across species. Given the size of the moms, their eggs are relatively big. The eggs are often described as looking like richly colorful fine porcelain, with shells so thin and translucent that the embryos can be seen. (Animals that prey upon tinamous typically hunt at night, so the brilliant colors don’t attract their attention.)

For polygamous species, multiple moms will lay eggs in the same dad’s nest (up to 16 eggs in one nest!); moms will lay a sequence of eggs in the nests of different dads. Nonetheless, the dads incubate the eggs alone, about 16–20 days. During incubation, the male is motionless and silent while on the nest; if a stranger (e.g., human) approaches, he may flatten himself over the eggs but will otherwise remain motionless. If he does leave the nest, he will cover the eggs and leave the nest for 45 minutes to 5 hours, during which time, he will feed (and presumably defecate), and he may vocalize. If he perceives a threat to the eggs or to hatchlings, he will try to distract the approaching threat by faking an injury — for instance, hopping on one leg, trying to take flight, then falling down. Tinamous haven’t perfected the distraction as well as killdeer, but they can sometimes be convincing.

Tinamou hatchlings are precocial, with a dense camouflage-enhancing covering of down. At first, the dad will take food to the chicks and drop it on the ground near them. Pretty soon, the male will leave the nest, softly calling them to come to him. Within a few days, he encourages the chicks to forage for themselves. Soon, they can run and chase their own insects to eat. Even so, if the chicks are threatened, the male will try to hide the chicks under his wings and belly and will freeze, motionless and silent.

Within about 10–20 days, the chicks can fly short distances, and by about 20 days, they’re self-sufficient, reaching adult size and weight within a few months. Once dad’s job is done, if it’s still the breeding season, he’ll seek female mates and start all over with a new brood. The youngsters are physiologically able to breed within 60 days, but they lack the behavioral knowledge to breed before they’re 12–18 months old.

It’s difficult to assess the conservation status of tinamous; many live in highly remote areas, unobserved by even the most dedicated of ornithologists. Their cryptic plumage and skulky behavior makes them hard to observe even when researchers are nearby. As far as can be determined, of the 47 species of tinamous, most are LC, Least Concern, and many tinamou species are able to find agreeable microhabitats within larger less-suitable environments.

Unfortunately, the IUCN lists 7 tinamou species as VU, Vulnerable, and 7 as NT, Near Threatened. These 14 species have more limited ranges, in which persistent habitat destruction, as well as habitat fragmentation, threatens their existence. Increasingly, their territories are deforested to make way for more farmland (crops or pastures) and timber plantations. Because neotropical forest lands lack nutrients, these farmlands are often abandoned within a few years, left fallow, and more deforestation occurs. In addition, the practices of burning farm fields and using pesticides pose added problems for neighboring tinamous. These toxic fumes and vapors can be particularly hazardous during breeding season.

Sadly, many tinamous are hunted and eaten by humans; hundreds of thousands were imported into North America in the previous century, until imports were banned there. Forest dwellers are less successfully hunted than tinamous living in grasslands, whom dogs can flush to take flight. It’s estimated that tens of thousands of tinamous are hunted legally, and many more are poached. Indigenous subsistence hunters kill countless tinamous each year; protective regulations are weak, nonexistent, or poorly enforced.

Other predators find tinamous tasty, too, such as species of falcons and numerous mammals — cats (e.g., jaguars), foxes, raccoons, skunks, weasels, and peccaries. Vampire bats pierce their flesh and lap up their blood. Tinamou eggs are sought by anteaters, snakes, monkeys, and opossums.

Though many humans have attempted to domesticate tinamous or to introduce tinamous to other locations (e.g., Europe, the United States), they haven’t succeeded. Tinamous fare better in zoos and menageries, and a few species respond well to captive breeding. Farmers may have mixed feelings about tinamous, as they’re known to glean the ground after harvest, to eat weeds, or to eat insect pests, but some will also happily dig up tubers, legumes, and other farm crops.

Tinamous are an ancient family, with their fossil record first appearing 23–5 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinamou#Fossil_record offers more details). Rheas, however, were already in South America when tinamous first appeared. Despite their ancient origins, they’re among the least studied orders of birds, and their behavior is poorly understood. Their diversity poses challenges to researchers, as tinamous in differing ecological niches show quite different behavior and adaptations. Unusual mating patterns and parental care, as well as various sex differences make study both more fascinating and more challenging. Their skulking behavior, avoidance from view, and cryptic plumage make observation difficult, too.

Elegant Crested Tinamou, Eudromia elegans

The genus name Eudromia comes from the Greek eu-, “well” or “good,” and -dromos, “runner,” and the Eudromia species definitely run well, especially to escape predators. As you may have suspected, elegans means “elegant,” which this crested species is. One of the Spanish names for this species is Perdiz copetona, “perdiz” meaning “partridge,” birds with a similar body shape.

This species lives mostly in the treeless low, flat grasslands and scrublands of the Patagonia region of southern Argentina (not found much in the western, Chilean part of Patagonia). (See https://ebird.org/map/elctin1 for a range map of eBird observations of this species.) Compared with North America, Patagonia extends from -40̊ to -55̊ south of the equator; north of the equator, Philadelphia is + 39̊ north, and Kodiak, Alaska, is + 57̊ north. Cool to chilly, especially in winter. This tinamou can be found anywhere from sea level to 8,200 feet (2,500 m, perhaps even 10,000 feet / 3100 m) in elevation. This species includes several subspecies with subtle differences in appearance and slightly different geographical distribution. Whatever location they inhabit, these tinamous don’t migrate, but when food is scarce, they cover more territory while foraging.

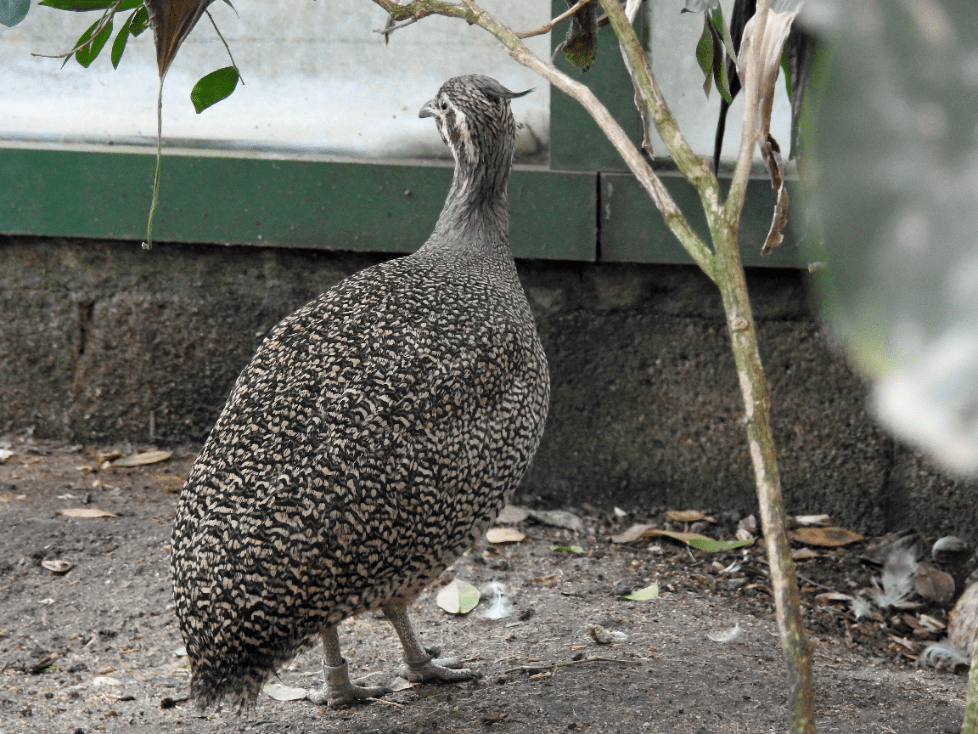

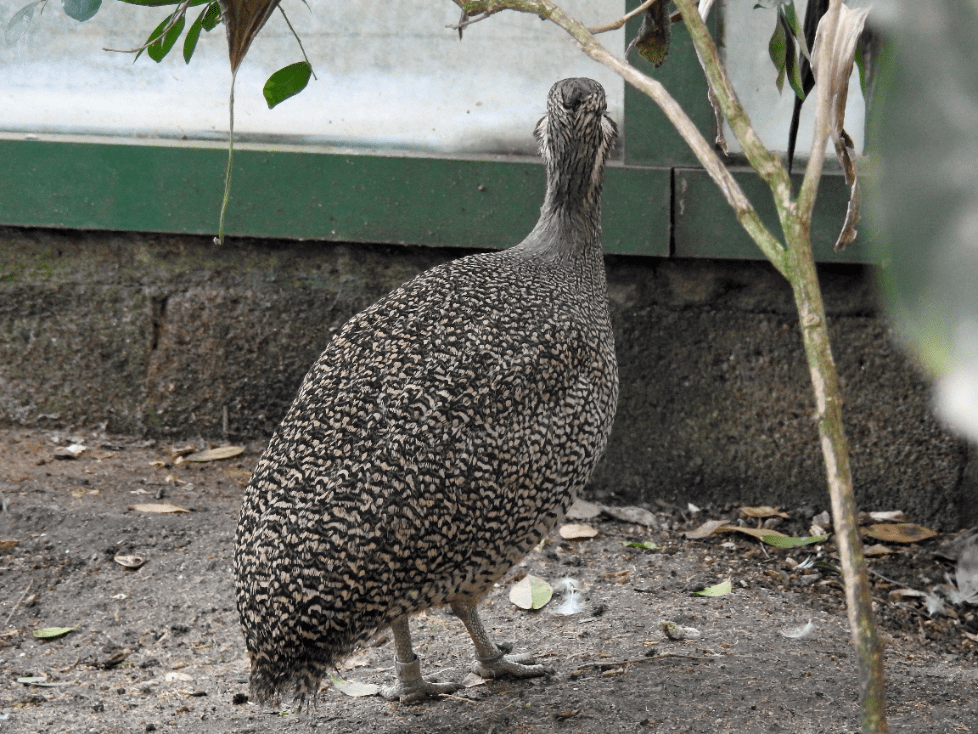

Figure 04. This view of an Elegant Crested Tinamou at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park shows its short tail and the absence of any rear-pointing toes.

Like other tinamous, it’s plump, with a minimal tail and short rounded wings (5.5–9″ / 13–22 cm). This tinamou species is relatively large, 14–17″ (37.5‒41.0 cm). Most females weigh slightly more than the males (females tending to weigh a little more than 1.6 pounds, males a bit more than 1.5 pounds). This tinamou species has just three forward-pointing toes and no rear-pointing toe (“hallux”), so it doesn’t grasp with its toes. Its short (2″ / 5cm) legs look brownish with buffy mottled scales.

Its plumage is a cryptic brownish gray and white pattern — described as “vermiculated” — which offers exquisite camouflage in the treeless grasslands it inhabits. Its facial plumage is brownish-gray, with short, narrow dark-chocolate streaks; also adorned with two white stripes that lead from above and below the eyes curving downward toward its neck. Its namesake modest crest extends back from the top of its head, up to 3″ / 7.5 cm; the crest can be raised or lowered, pointed up or back, while curving upward slightly at the tip. Its decurved (downward) pointed bill is grayish black, slightly more than 1″ long, and about 1/4″ wide by 1/4″ deep. Its eyes are caramelly brown.

Figure 05. The swoop from its downcurved bill to its upcurved crest reveals why its common name is Elegant Crested Tinamou; its liquid-caramel eyes add to its appeal.

Like other tinamous, this tinamou isn’t easily seen but can be easily heard. Soon after hatching, these chicks start making thin peeping calls, which develop to be similar to the vocalizations of adults within 20 weeks, though not as strong or as rich as adult vocalizations. As you can hear for yourself at https://xeno-canto.org/species/Eudromia-elegans, their whistles can be all rising and increasing in volume or rising then falling in pitch and in volume. They also make squeaks, two-note calls, rattles, and more, such as “guttural, pumping, sharp whistles [xeno-canto: XC60338], nasal or foghorn-like, whistle-warbles, twittering, cat meowing or whining types” (from https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/elctin1/cur/sounds#vocal , available by subscription).

Singing increases during breeding season but extends well before and after it. Singing can be heard all day, sometimes even long before sunrise, but most singing happens during the early morning. Both sexes vocalize but some vocalizations are peculiar to females, showing dominance.

When startled, these tinamous will (reluctantly) take flight, and their energetic wingbeats are loud enough to be heard at close range. Once in the air, they alternate rapid wingbeats with flapless glides. They get up to about 10–20 feet into the air and typically fly about 100–900 feet at a time. Like other tinamous, their short wings and near-absent tail make steering challenging; they easily fly out of control, crashing into obstacles. Whenever possible, they avoid flying; when they sense a threat, they peek around to spot the threat, then hide behind cover, or flatten their bodies and heads on the ground.

Reticent flyers, they spend almost all of their time on the ground, walking long distances, as needed, to forage for seeds, fruits, buds, and leaves. When food is abundant, however, they’ll forage within a small area, gleaning food from the ground, using the bill (not the feet). Occasionally, these tinamous will leap up to snatch fruit, flowers, and leaves. They also eat insects and other invertebrates, especially during the summer. According to Avibase, invertebrates make up about 10% of their diet, seeds about 30%, fruits about 30%, and other plant matter the remaining 30%. Like other tinamous, they’ll sometimes swallow grit, to aid digestion in the gizzard.

Unlike some other tinamou species, Elegant Crested Tinamous are relatively social, foraging in flocks of 5–10 tinamous. Outside of breeding season, they may form flocks of 30‒40 or more birds (up to 100 in winter!). Researchers haven’t yet been able to find out much about tinamou food selection, food storage, quantitative analysis of food items, drinking, defecating, casting of pellets, metabolism, or temperature regulation in this species.

Researchers have observed that this species roosts on the ground, usually on the north side of low vegetation (facing the equator), which shields them from strong chilly winds coming from the south. To form their roost, they plop down into the middle of the roost spot, then they revolve, using their feet to kick outward creating a circular bowl. During the day, they forage most in the early morning and the late afternoon; in the winter months (summer in the northern hemisphere), they must spend more time foraging and cover more territory, to eat enough food. At midday, they take dust baths, briefly sunbathe, and rest in the shade.

Both males and females typically start breeding more than a year after hatching. Like other tinamous, female Elegant Crested Tinamous are polyandrous, and males are polygynous. Each male digs his own nest bowl (<1″ / 2 cm deep, about 7.5″ / 20 cm wide) in a clandestine location — in clumps of vegetation, under low bushes, or the like. He makes his nest bowl in the same way that tinamous create their roosts — using his feet to kick out dirt as he rotates in the middle of the bowl. He might later add a few feathers or other dry matter, perhaps with help from a female.

After digging his nest, he calls for females to visit him. Groups of 2–3 females stop by, copulate with him, then lay their elliptical, glossy lime green, unmarked eggs in his nest. (See https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/324861702 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/324087108 for photos of the eggs of Elegant Crested Tinamous.) Each female lays 2–3 eggs and leaves the male to incubate 5–16 eggs, depending on how many females have stopped by his nest. In a given breeding season, a female may lay 30–40 eggs, having laid them in the nests of numerous males.

During the breeding season, each male develops a brood patch, and he starts incubating the eggs as soon as 5–6 have been laid in his nest. When he leaves the nest — to forage, defecate, and so on — he covers the eggs with feathers, twigs, or leaves. After about 19–21 days, the eggs hatch, synchronously. The precocial chicks hatch already covered in natal down, and they can soon leave the nest to run and forage for themselves. Nonetheless, they’ll return to the nest and stay with the male for up to 3–4 months after hatching, while they exchange their natal down for juvenile plumage — which is very similar to adult plumage. (See https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/615275533 for a photo of an Elegant Crested Tinamou dad out strolling with two of his chicks.)

On January 21, 2019, Andrew Stehly, associate curator of birds at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park, reported that “The pair [of Elegant Crested Tinamous] recommended for breeding by the Species Survival Plan (SSP) was living at our Bird Breeding Center (BBC). It’s a nice, quiet area, but not much was happening with them . . . . However, we had another pair at Hidden Jungle, and they had raised six chicks in there. So last season, we switched the locations of the two pairs. Sure enough, Hidden Jungle was just the right spot!”

Figure 06a, b. In 2018, this charming Elegant Crested Tinamou was seen in the Hidden Jungle at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park.

Hidden Jungle wasn’t the only romantic spot there, however. Another breeding pair successfully reproduced numerous chicks at the Safari Park’s Condor Ridge. To look at 16 photos of Elegant Crested Tinamous at zoos around the world, see https://app.zooinstitutes.com/animals/elegant-crested-tinamou-san-diego-safari-park-25403.html . To watch a charming child-narrated video of a pair (after a brief advertisement), see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NvKEdgpH1BA .

Elegant Crested Tinamous have a large geographic range (Avibase estimates, 580,000–810,000 square miles / 1.5–2.1 million km2), so they’re considered to have LC, Least Concern, IUCN Red List status. A little more than 70% of this species survive annually. Though their global population isn’t known, it’s considered “fairly common.” Nonetheless, their population is declining, at least partly due to reduction in suitable habitat, as well as to hunting, both for their meat and for their eggs. Compared with other species, there’s a low prevalence of trade in these tinamous. Even so, in territory near to human settlement, not only hunting but also farming practices pose a threat to this species. There are no known conservation steps being taken for this species, but there are conservation sites within their range.

Unfortunately, humans aren’t this tinamou’s only predators. Their eggs and chicks are also preyed upon by mammals — foxes, skunks, opossums, armadillos — and birds — hawks, falcons, owls, caracaras. Like other tinamous, they’re both skulky and wary; their ability to hide, seeming to disappear is their chief defense against predation. In captivity, Elegant Crested Tinamous can live to be at least 7‒9 years old. The oldest recorded age was a little more than 18 years. Average generation length is 5–6 years.

The fossil record includes a nearly complete specimen of a tinamou within the Eudromia genus, probably dated to more than 12,000 years ago; its skeleton was nearly identical to both contemporary Eudromia tinamous, except that it was larger. A South American specimen of this species was first identified in 1832 by Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, a French zoologist who coined the term ethology (“ethologie”) in 1854.

While the Tinamidae family, in general, is poorly studied, the Elegant Crested-Tinamou is more often studied than other species. Nonetheless, information is still needed regarding many aspects of its behavior, its territoriality and population, and its early development.

Figure 07. Both Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s eBird website and the iNaturalist website offer cellphone apps, making it easy for anyone to record any species of bird a person has observed. Through these apps and websites, more than 8,000 observations of Elegant Crested Tinamous have been posted, available for viewing by professional ornithologists and researchers, as well by as amateur naturalists and anyone else interested in seeing these and other birds.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has collected 7,662 eBird observations of this species. In addition, its Macaulay Library has posted 1,865 photos (Elegant Crested-Tinamou – Eudromia elegans – Media Search – Macaulay Library and eBird), 58 audio recordings, and 10 videos of this species of tinamou. In addition to observations recorded through eBird, amateur and professional naturalists also record observations of this species through iNaturalist. As of February 7, 2026, there had been 711 observations of this species, many of which include photos, which you can see at https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?taxon_id=20637. For instance, for closeups of tinamou feathers, see https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/336175268 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/331838687 and https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/336243545 . To see an Elegant Crested Tinamou flat on the ground with its head up (perhaps a male incubating eggs?), see https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/19646965 .

References

Tinamidae, Tinamous

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, and Irby J. Lovette. (2015). “Tinamidae” (pp. 38–39). Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Tinamous (Tinamidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.tinami1.01.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tinamou

Elegant Crested Tinamou, Eudromia elegans

- Gomes, V., F. Medrano, and G. M. Kirwan (2024). Elegant Crested-Tinamou (Eudromia elegans), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg and M. G. Smith, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.elctin1.01.1

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=4E215E82

- https://ebird.org/map/elctin1, range map of eBird observations

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elegant_crested_tinamou

- https://sandiegozoowildlifealliance.org/story-hub/zoonooz/fresh-feathers — San Diego Wildlife Alliance Homepage, Story Hub; STORIES | Animals, January 21, 2019, “Fresh Feathers”

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NvKEdgpH1BA, Elegant Crested Tinamou | Paws for a Minute. Ocean State Media

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22678289/263683694, Elegant Crested Tinamou, Eudromia elegans

- BirdLife International. 2024. Eudromia elegans. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2024: e.T22678289A263683694. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2024-2.RLTS.T22678289A263683694.en. Accessed on 07 February 2026.

- https://zooinstitutes.com/animals/elegant-crested-tinamou-san-diego-safari-park-25403.html — Eudromia elegans / Elegant crested tinamou in San Diego Safari Park and 15 other zoos

Etymology of Bird Names

- Gotch, A. F. [Arthur Frederick]. Birds—Their Latin Names Explained (348 pp.). Poole, Dorset, U.K.: Blandford Press.

- Gruson, Edward S. (1972). Words for Birds: A Lexicon of North American Birds with Biographical Notes (305 pp., including Bibliography, 279–282; Index of Common Names, 283–291; Index of Generic Names, 292–295; Index of Scientific Species Names, 296–303; Index of People for Whom Birds Are Named, 304–305). New York: Quadrangle Books.

- Lederer, Roger, and Carol Burr. (2014). Latin for Bird Lovers: Over 3,000 Bird Names Explored and Explained (224 pages). Portland, OR: Timber Press.

Miscellaneous

Text and images (except tinamou eggs) by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2026.

All rights reserved.

Leave a comment