Otidiformes/Otididae and Struthioniformes/Struthionidae

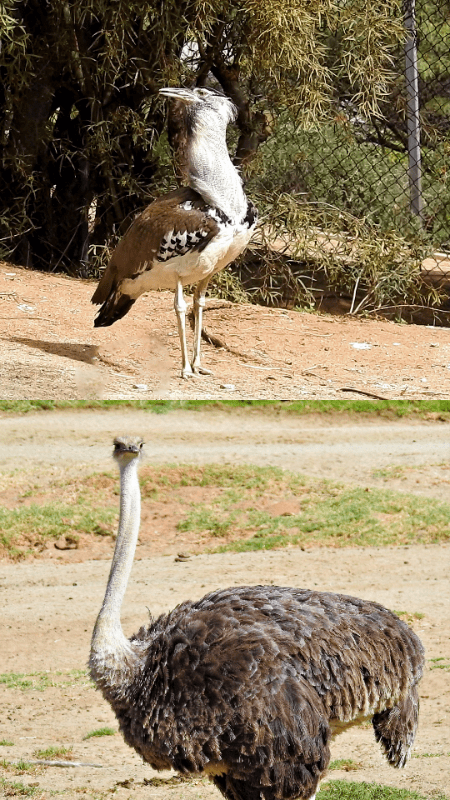

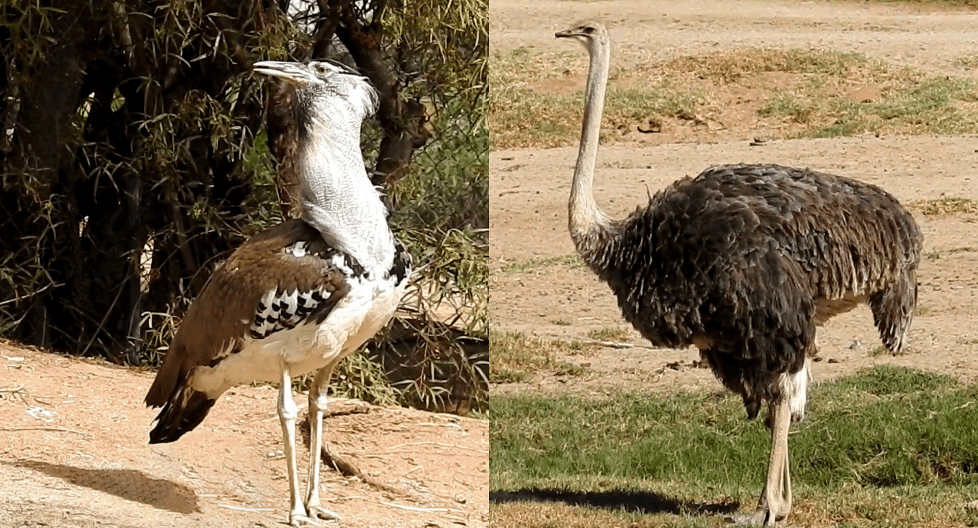

Figure 01. Big Birds: Kori Bustards weigh hundreds of times as much as typical birds, yet they can still fly. Ostriches can’t fly, weighing more than two thousand times as much as typical birds.

According to https://biologyinsights.com/how-much-does-the-average-bird-weigh-2/, the median weight of birds is about 1.4 ounces (40 grams). (Median size actually gives a better estimate than the mean, which might overweight the relatively smaller number of the heaviest birds.) In comparison, Kori Bustards weigh about 23 pounds (368 oz.). That is, the average Kori Bustard weighs 263× as much as the typical bird. Ostriches weigh about 230 pounds — about 10× as much as a Kori Bustard, 2,630× as much as the typical bird! Definitely, they’re big birds! Among these big birds, the males weigh much more than the females.

Kori Bustards weigh 13–42 pounds: females, 13 pounds (5.9 kg); males, 24–42 pounds (∼33 pounds, 10.9–19 kg).

Great Bustard males weigh 12.8–39.7 pounds (5.8–18kg); females weigh 7.3–11.7 pounds (3.3–5.3kg).

Ostriches weigh 140–320 lbs. (∼230 pounds, 63.5–145 kg): males, 220–344 pounds (∼282 pounds, 100–156 kg); females, 198–243 pounds (∼220 pounds, 90–110 kg).

Both birds also belong to bird orders that contain just one bird family. The Otidiformes order contains only the Otididae family. The Struthioniformes order contains only the Struthionidae family.

Otidiformes, Otididae, Kori Bustard

The two heaviest flighted birds in the world are in the Otididae family — specifically the Kori Bustard (Ardeotis kori) and the Great Bustard (Otis tarda). The Otididae family includes 12 genera, 26 species. Among Kori Bustards, males are heavier, taller, have longer wings, and have longer, wider, and deeper bills than females.

Figure 02. In the first century a.d., Pliny the Elder (a.d. 23–79) gave these birds the Latin name avis tarda or aves tardas, which was later Anglicized to the name “bustard.”

Many species of bustards are polygynous, with females choosing one or more partners from the males in the area. These males engage in elaborate courtship displays to woo the females. (To see a displaying bustard, check out https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=korbus1&mediaType=video&sort=rating_rank_desc, then find this brief video, Macaulay Library ML648429313 .) Among the polygynous species, the females take responsibility for all parenting duties.

Among the bustard species that are monogamous, however, the males participate in parenting, as well, sometimes with added help from a male offspring from a previous breeding season. The account in Birds of the World didn’t indicate whether Kori Bustards are polygynous or monogamous.

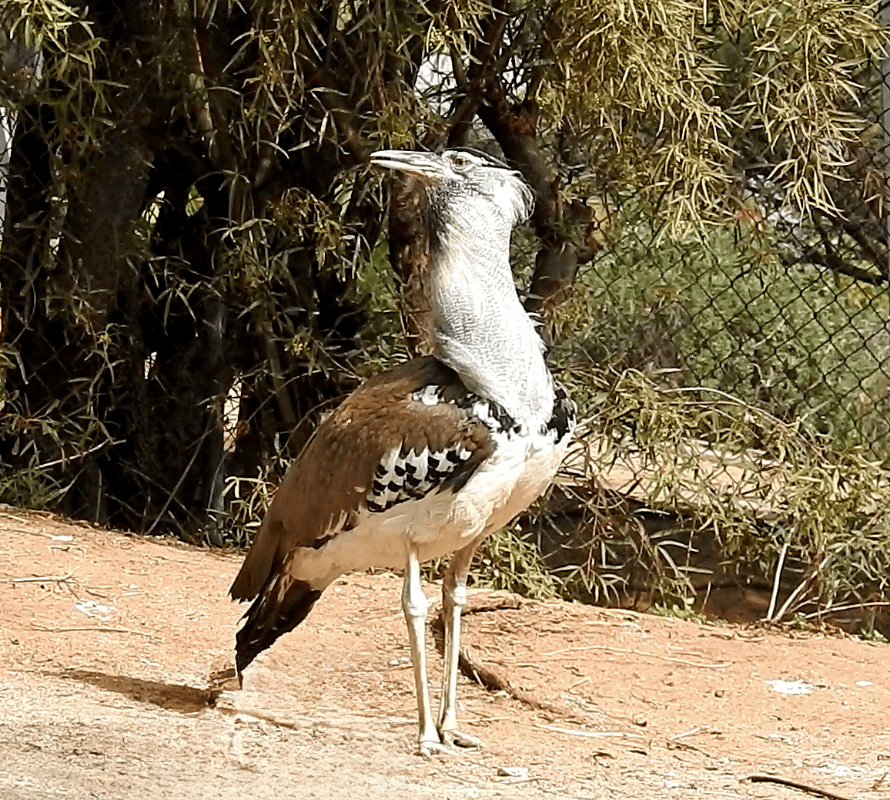

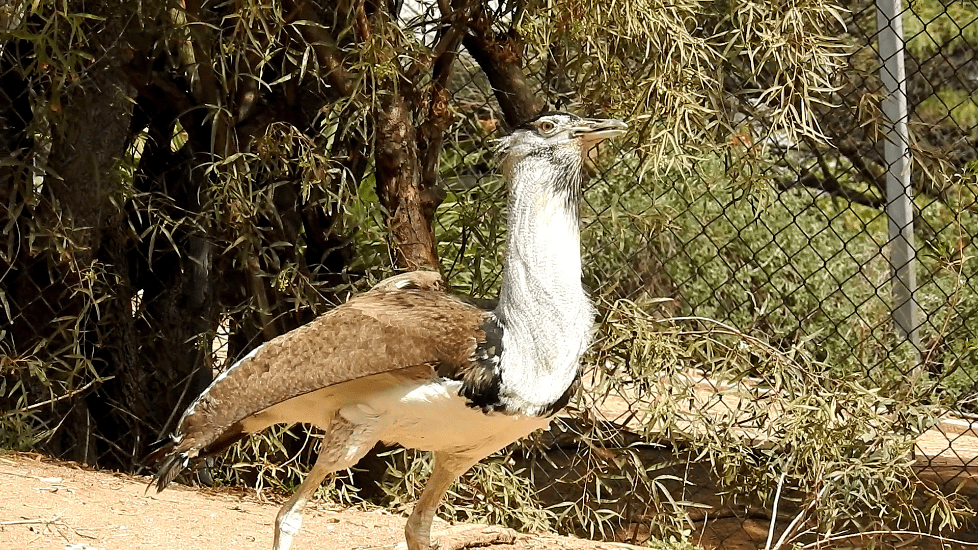

Figure 03. When these Kori Bustards are hanging out at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park, they can relax on a hot day, without worrying about predators or where to find their next meal.

Like other bustards, Kori Bustards nest on the ground, typically a shallow scrape, sometimes thinly lined with grass. It might be placed in partial shade from a tree or near a clump of grass. The female lays 1 or 2 eggs, which she (possibly with help) incubates for about 24 days. Within a day or two after hatching, the precocial downy hatchling will be led by the parent to where it can find food for itself. Both adults and youngsters have cryptic — camouflaged — plumage, but the ground placement of their nests make them vulnerable to predators. Youngsters are able to fly after about 31 days.

Figure 04. This female Kori Bustard is enjoying a scratch and a stretch on a warm day.

The genus Ardeotis includes 4 species of similar-looking, long-legged, long-necked bustards. They prefer to walk or run on their strong legs and large toes, rather than to fly. In flight, their long, broad wings have raptor-like feathered “fingertips” (for a video of takeoff, flight, and landing, see https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=korbus1&mediaType=video&sort=rating_rank_desc, ML201266401, or for flight and landing, see ML256137261; or for takeoff and flight, see ML622575912). (While you’re at it, check out ML201545131, a Carmine Bee-eater hitching a ride on the back of a Kori Bustard, as a perch for hunting insect prey.)

The bustards’ omnivorous diet includes lots of insects, an array of plant parts (fruits, seeds, leaves, bulbs, young shoots, etc.), some snails, and a sampling of small vertebrates, such as lizards, rodents, snakes (not too large), and bird eggs and nestlings. Opportunists, they also scavenge dead animals such as roadkill.

Figure 05. With her fluffy neck feathers and her cryptic plumage, this female Kori Bustard seems to know she’s lovely.

The Kori Bustard makes its home in the grasslands, savannas, and semiarid deserts of Africa. In the hot, dry season, they may also be found in woodlands. They’re not migratory, but females with chicks will sometimes travel longish distances to escape from predators.

According to Birds of the World, the male Kori Bustards make deep, resonant, nasal utterances when displaying. To hear other vocalizations by this species, please see https://xeno-canto.org/species/Ardeotis-kori, for four samples.

Kori Bustards have Near Threatened conservation status, largely due to habitat destruction, as well as hunting. They also suffer inordinately from collisions with electricity cables, vehicles, and fences, probably because they have limited forward binocular vision. When wildlife preserves are available, these bustards can be seen more abundantly. When not experiencing environmental threats, they live about 26 years (28 maximum recorded), with a generation length of more than 11 years.

Figure 06. This Kori Bustard is enjoying some shade on a hot day at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park.

There once was a Bustard named Kori

It liked hunting insects as quarry

Long legs and big toes

It oft struck a pose

When eating, it was omnivor-y

Struthioniformes, Struthionidae, Ostriches

Weighing 10× as much as Kori Bustards, which can fly, are Ostriches, which can NOT fly. Ostriches are among the flightless (or very weakly flying) birds known as “ratites.” Other ratites are cassowaries, emus, rheas, kiwis, and tinamous.

Figure 07. Common Ostriches can be found throughout many savannahs, semi-arid deserts, and even some open woodlands, across the middle of Africa — between the Sahara and the equator — and in southern Africa.

The bird order Struthiformes contains just one family, Struthionidae, which includes just one genus, Struthio, which includes two species: the Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus; first described, 1758, Carl Linnaeus) and the Somali Ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes). The Common Ostrich is far more common (listed as of “Least Concern” by the IUCN) than the Somali Ostrich (listed as “Vulnerable”).

You’re probably not surprised that the Common Ostrich (which I’ll just call “ostrich” after this paragraph) is, by far, the largest bird in the world — heaviest and tallest — but you may be surprised to hear that it’s also the fastest-running two-legged animal in the world, reaching speeds of 43.5 mph (70 km/h). On four legs, cheetahs can run up to 60 mph, but they can’t sustain that speed for long. The closest two-legged competitors for the ostrich are the emu and the cassowary (29–31 mph each), both of which are also flightless and long-legged; in fourth place is the (flighted) roadrunner (20–27 mph).

Nary an ostrich is seen in the sky

But on strong legs, it seems to fly

Evading predators, it swiftly passes

Leaving lions on their ***

Figure 08. This Common Ostrich is strolling at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park on its two-toed feet and muscular legs. If , however, one of the park’s big cats managed to get to this area, the ostrich could speed up. If the ostrich had a head start, it could outrun the big cats, who would give up pretty quickly, while the ostrich could keep running.

Ostriches sustain their enormous size almost entirely by eating plant matter, roots and all. These plants are also thought to provide them with some of the water they need, in addition to any water they can find in waterholes and other sources. They’ll also occasionally snack on seeds, invertebrates, and even a few small vertebrates.

Figure 09. Ostriches forage along the ground, devouring (mostly) plant matter.

Ostriches breed polygamously. In a given breeding season, each male will mate with many females, and the females may have multiple male partners, as well. A video of a male ostrich’s display and copulation with a female can be seen at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostrich (also shown: ostrich egg alone and in comparison with a chicken egg and a dollar bill).

While the females’ eggs are developing prior to laying, each male will scrape a big shallow dimple in the ground, in an open area with easy visibility in all directions. Ostrich eggs are the biggest eggs in the world, but given the enormous size of the female moms, the eggs are actually the smallest, relative to the body size of the mom. (The chicken-sized, flightless kiwi lays one of the largest eggs, relative to body size — weighing up to 1/4 of the mom’s body weight.)

Figure 10. Male ostriches outweigh females by up to 100 pounds, and males (82–108″, 210–275 cm) can be 13–33″ taller than females (69–75″, 175–190 cm). In addition, male ostriches have mostly black feathers, whereas females’ feathers are mostly dark brown. Both sexes have mostly bare heads (a few scattered downy feathers), as well as long bare necks and legs.

The senior female (in rank) deposits her eggs in a particular male’s nest before any others do. Then up to 7 more females will lay their eggs in the nest, too, leaving up to 25 eggs in the nest; their job’s done. They leave the male, with help from the highest-ranking female, to incubate their offspring for the next 6 weeks or so.

About 3 days after the eggs hatch, the parents lead their chicks to forage for food. The youngsters stay with their parents for up to a year afterward. Occasionally, families of ostriches will cross paths, and one pair of parents may end up with both broods of youngsters. Observers have seen up to 300 chicks with just one set of parents, presumably after numerous such encounters.

(These Macaulay Library videos show some ostrich youngsters, some with their parents: https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=ostric2&mediaType=video&sort=rating_rank_desc . Video of chicks foraging, ML200805791; chicks foraging with two parents, ML200930091 and ML646650931, older youngsters with two parents, ML627079976; and a parent with chicks, foraging, ML200943741.)

Figure 11. What’s not to love about this very big bird?

Near the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park is a road sign advertising the sale of ostrich eggs. According to Wikipedia, Ostriches are farmed around the world, not just for their eggs, but also for their meat, their pelt (leather), their feathers, and even their oil (from “ostrich fat”). At one time, the plume trade was causing significant population decline, but that has subsided, and habitat destruction has much more impact on their population now. In addition, in the wild, ostriches are highly vulnerable to predation as eggs and chicks, but when predators aren’t a concern, ostriches do well, designated species of “Least Concern” by the IUCN. In fact, ostriches living in managed care are among the longest-lived birds. Maximum known longevity 50 years, range 26–50 years. Average generation length 14.5–15 years.

References

- Miscellaneous

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fastest_animals?wprov=sfla1

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiwi_%28bird%29?wprov=sfla1

- https://biologyinsights.com/how-much-does-the-average-bird-weigh-2/

- https://www.richardalois.com/bird-facts/how-much-does-a-bird-weigh

- https://www.thayerbirding.com/how-much-does-a-bird-weigh/

- Otididae, e.g., Kori Bustard

- Collar, N. and E. Garcia (2020). Kori Bustard (Ardeotis kori), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.korbus1.01

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, Irby J. Lovette. (2015). “Otidiformes,” “Otididae,” p. 103. Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Bustards (Otididae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.otidid1.01

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bustard?wprov=sfla1

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=4FC41CA0

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=4FC41CA0DC1B12AF&sec=lifehistory

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22691928/246077557

- Struthionidae, Ostriches

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ostrich

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Struthionidae?wprov=sfla1

- Folch, A., D. A. Christie, F. Jutglar, and E. Garcia (2020). Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ostric2.01

- Winkler, David W., Shawn M. Billerman, Irby J. Lovette. (2015). “Struthioniformes,” “Struthionidae,” pp. 35–36. Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. Barcelona: Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- Winkler, D. W., S. M. Billerman, and I. J. Lovette (2020). Ostriches (Struthionidae), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, P. G. Rodewald, and T. S. Schulenberg, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.struth1.01

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?avibaseid=2247CB05

- https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/species.jsp?lang=EN&avibaseid=2247CB050A76CF8E&sec=lifehistory

- https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/45020636/280828427

Text (including “poems”) and images by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2026.

All rights reserved.

Leave a comment