Searching for the Meaning of It All at the Oxford English Dictionary, A Memoir,” by John Simpson

The Word Detective: Searching for the Meaning of It All at the Oxford English Dictionary, A Memoir, by John Simpson. New York: Basic Books.

Contents

- Introduction: The Background to the Case, ix–xvi

- 1 Serendipity, Perhaps, 1–22

- 2 Lexicography 101, 23–38

- 3 Marshallers of Words, 39–64

- 4 The Longest Way Round, 65–96

- 5 Uneasy Skanking, 97–127

- 6 Shark-infested Waters, 129–145

- 7 OED Redux, 147–178

- 8 The Tunnel and the Vision, 179–208

- 9 Gxddbov Xxkxzt Pg Ifmk, 209–237

- 10 At the Top of the Crazy Tree, 239–261

- 11 Shenanigans Online, 263–292

- 12 Flavour of the Month, 293–328

- 13 Becoming the Past, 329–340

- [Back matter]

Introduction: The Background to the Case, ix–xvi

Long before John Simpson (author of this book) joined the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 1976, there had always been a “tussle between the publishers at the University Press (OUP) in Oxford and the heroic dictionary editors” (from the viewpoint of the editors). Responsible OUP folks felt obliged to scrupulously monitor the time and money expended on the OED, whereas the OED folks felt compelled to spend however much time and money was needed to ensure that the dictionary reflected the highest possible quality of scholarship and writing. You can see the problem.

One reason that the OED requires its editors to spend so much time (and therefore money) is that it’s not just a list of words and definitions. Instead, it’s a historical dictionary, showing when and how words and phrases entered the English language, from its first emergence “1,500 years ago.” Doing so requires lots of detective work.

The OED also describes how language is and has been used by real people; it makes no attempt to prescribe how language should be used by anyone.

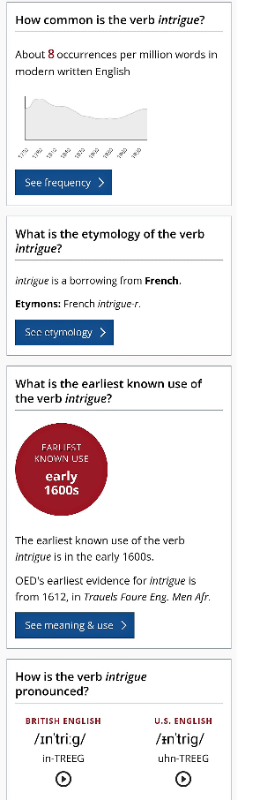

Simpson illustrates how the OED reveals word histories by interspersing brief illustrative word histories throughout his book. In the introduction, he illustrated how intrigued had changed from its introduction in 1612 to the present day.

In 1612, the first known printed use of intrigue was as a verb meaning “to trick or deceive (someone).” The word goes back even farther, in French, to 1532, when the French borrowed it from Italy. In addition to an extensive history, the OED also offers information on its frequency of use across time, its etymology (origins), its pronunciation, compounds using “intrigue,” and other forms of the word (e.g., nouns, verbs).

1 Serendipity, Perhaps, 1–22

Simpson subtitles his book, “A Memoir,” and he does intersperse occasional personal information about himself and his family, but these memoirs play a very minor role, as most of the book addresses the OED and his role as editor for the OED.

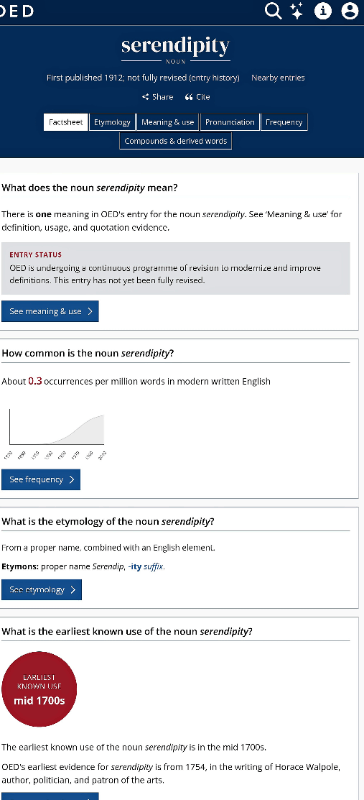

Among the words Simpson chronicles in this chapter, serendipity captured my attention. In 1754, British art historian Horace Walpole wrote to British diplomat Horace Mann about a felicitous discovery, saying “This discovery . . . is almost of that kind which I call Serendipity.” Apparently, he coined it, based on a fairytale referring to Serendip, a former name for Sri Lanka.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also reveals the linguistic history of juggernaut, epicentre (epicenter), and debouch.

Simpson describes how he almost accidentally became an editor for the OED, an occupation he hadn’t considered while studying English literature in a college very much not Oxford University.

More than a century before, in 1857, the Philological Society of London had been lamenting that there were no adequate contemporary English dictionaries at the time. (Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary was already more than a century old by then.) For the next 20 years, the society members gathered materials while looking for a funding source — ideally, a book publisher or a university — and a clever scholar willing to head up such an endeavor. At last, in 1879, the society persuaded Oxford University Press (OUP) to fund the project, as well as Scottish schoolmaster James Murray to be the dictionary’s chief editor.

Unlike many popular dictionaries of the day, the society wanted the Oxford English Dictionary to base its entries on historical and contemporary evidence of how the language is actually used and has actually been used. In addition to giving definitions for the entries, the OED would offer detailed etymologies, with quotations to illustrate and document each meaning of a word. To gather this evidence and these quotations, Murray came up with a crowdsourced methodology. That is, he appealed to “readers” around the world to send him illustrative quotations, with each quotation pointing to its exact source (author, book title or other publication name, page numbers or other information). He sought as wide a variety of quotation sources as possible — newspapers, trade journals, academic papers, literature, and so on. He invited people from all walks of life, not just academics, to contribute quotations they had found.

By the early 1880s, Murray and his team had enough documentary evidence to start with the “A to Ant” words (published in 1884), and then continued through the alphabet. The idea was to publish the dictionary in installments, through Z. Purchases of these installments — often by subscription — would start to repay the OUP for its investment, while Murray’s team continued working on the remaining letters of the alphabet. (In the Victorian era, many publications were being published in installments, “serial publications” — even fiction, such as the works of Charles Dickens in 1836.)

Murray oversaw the rest of the letters, into the “T” words, but he died before the final installment was published in 1928. Unfortunately for the OUP, English continued to add new words and new word meanings even after 1928. A 1933 Supplement volume was published, but it didn’t finish the job, either. By the time Simpson was hired in 1976, the OUP had resigned itself to creating a much more comprehensive multivolume Supplement.

Author of the Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien, had been an assistant editor on the OED, before becoming an English Language and Literature Professor and then a world-renowned author of fantasy. His love of philology and of words influenced the languages he incorporated into his novels.

2 Lexicography 101, 23–38

Simpson’s job as a lexicographer was his very first paid job after finishing college. The OUP had no intention of revamping the entire OED at that time. Instead, the editors — including him — were to update the Supplement — now to occupy four full volumes, rather than the single 1933 volume.

Early on, Simpson wasn’t invited to write definitions. Instead, he was given a translated text and asked to find relevant quotations for words in the text — new words, new meanings for existing words, or older quotations for existing words. Once these were found, he was to write out the relevant quotations on index cards, along with the reference information for the text where he found the quotations.

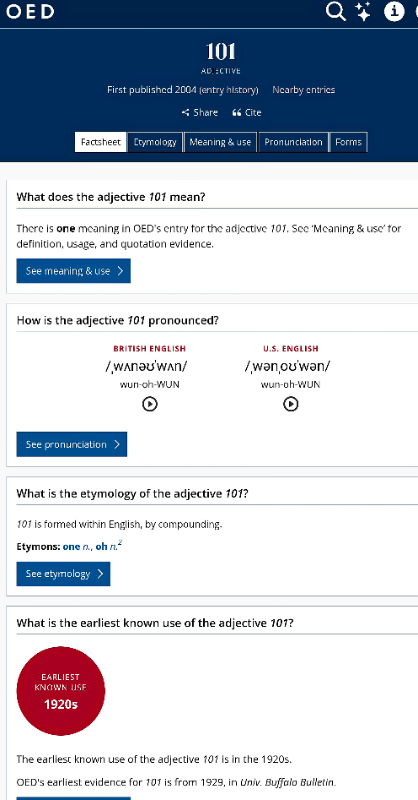

The OED also includes some numerals, such as 101, defined as a “postmodifier: designating an introductory course at U.S. colleges or universities . . . ” and may also be applied to any basic facts about a particular subject.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also probes the linguistic history of paraphernalia (nope; never was paraphernalium).

To detect these additions, and differentiate them from existing words, meanings, and quotations, Simpson had easy access to all volumes of the First Edition of the OED. By looking at the existing OED, he could discern whether what he thought was a new word or a new usage or an older quotation did or did not already exist in the OED. Simpson’s training was, in essence, to follow the same procedure followed by the myriad “readers” who contributed to the original OED and to every update that followed. “I was joining a group of thousands of people who, over the previous hundred years or so, had contributed . . . to the dictionary’s word-store” (p. 33). “I enjoyed the steady methodology by which you gradually built up information for words” (p. 38).

3 Marshallers of Words, 39–64

About a month after starting work at the OED, Simpson was given a chance to define words, starting with queen. Clearly, the first OED had plenty to say about queen, so it was Simpson’s job to find out how English had changed regarding queen and to write an update. As a trainee, he was even given a head-start with batch of citation index cards to use for drafting his update. Perhaps he could find new meanings or at least new nuances of meanings, new expressions including queen, any new historical information that had come to light, as well as newer, more contemporary quotations. His updates would be included in the four volumes of the Supplement, not a wholly revised OED. “It wasn’t our job to update everything; we would never finish if we started along that route” (p. 40).

As he saw it, his job involved three phases:

Phase 1. Build up a collection of index card citations, retrieving as many as he could find, using the OED’s archives— this process might reveal intriguing possibilities that had been missed previously or had been added since the last update. Some “readers” (contributors of quotations) were prolific, and he grew to recognize their handwritten contributions.

Phase 2. Gather additional information, as needed, from reference books, using the OED’s extensive but targeted reference library. Specialized dictionaries (e.g., quotations, biographies, slang and jargon, occupations) and general dictionaries and concordances (complete lists of words in a text, in alphabetical order) from around the world figured prominently.

Phase 3. Use the gathered information to write an update of the definition and all the other elements needed for that dictionary entry; typically, he’d organize the information and come up with some key ingredients for the definition before starting to write it.

In addition, he needed to come up with a representative sampling of the quotations, choosing those that best illustrated the meaning, while also representing a diversity of literary and non-literary sources. He sought to include “more global English, more slang, more popular or regional magazines, more everyday, informal jargon” (p. 53).

It took 44 years (1884–1928) for the entire OED to be published, from first volume to last — not even counting the 1879 date when Murray was hired. By comparison, the German Deutsches Wörterbuch, started by the Grimm brothers in 1854, wasn’t completed until 1961 (107 years later!). The first volume of the multivolume Dutch dictionary was published in 1864, and the final one was published in 1998 — 134 years. By comparison, the OED was published at lightning speed.

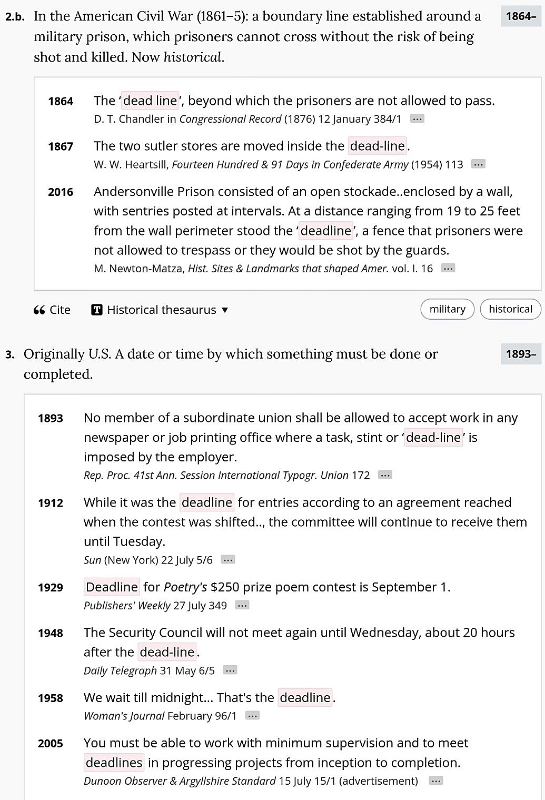

One of the first meanings of deadline was far more literal than how we now use the term.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also illuminates the linguistic history of queen, court martial, marshal, and marriage.

When Simpson finally completed queen, his first dictionary entry, he “felt a thrill of connection with the earlier editors in the [1800s], who used precisely those procedures in their own work. I had the best job in Oxford” (p. 63).

4 The Longest Way Round, 65–96

As Simpson grew more comfortable and ensconced in his role as an OED editor, he relished finding books and other resources offering him opportunities for seeing new words, new word meanings, new expressions, older quotations documenting existing words. Neither he nor his colleagues realized that they were watching the end of old technologies as new ones appeared on the horizon. Hand-written index cards would be replaced by digital citations; hot-metal type would be replaced by digital typesetting. What continued, however, was the tradition of having “readers” crowdsource the citation “cards” — though they would no longer be submitted on physical cards, the crowdsourced citations would continue to be welcomed by OED editors.

The OUP seemed quite content just to publish the most recent four volumes of the OED Supplement and be done with it. The editors, however, were champing at the bit to be able to overhaul and update the entire OED. Meanwhile, just down the road (sort of), the Encyclopædia Britannica was continually being updated, publishing new editions. The OED was getting a reputation for being antiquated. Even linguistics had undergone transformative changes, which the OED didn’t reflect. The wording, too, seemed old-fashioned, out-of-date.

The chief editor sensed the restlessness among the editorial staff and occasionally assigned them their own projects, such as an Oxford Dictionary for Scientific Writers and Editors, various sizes of dictionaries, and a Junior Dictionary. Simpson was assigned, Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs.

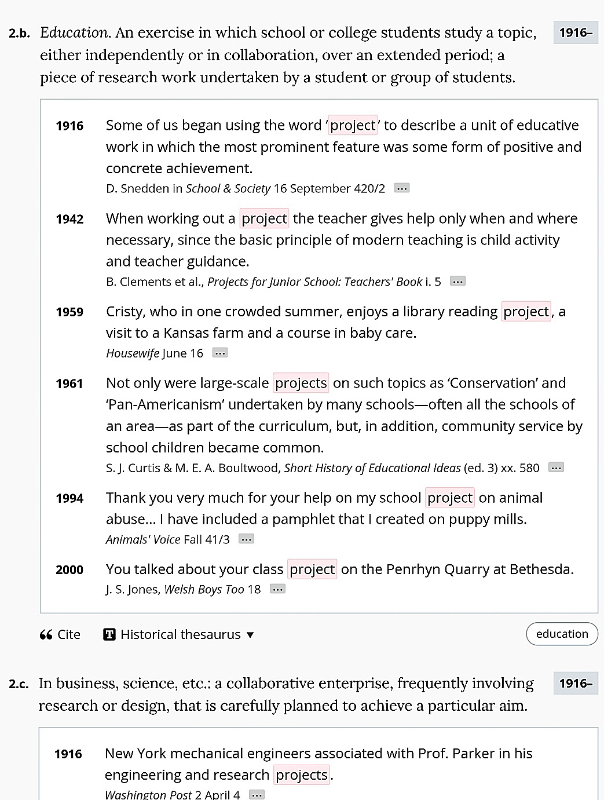

When project entered the English language from Latin, about 1450, it pointed to a structure that projected outward. The use of project to mean more of a plan arrived in English from French, perhaps by way of Italian and Spanish, in the 1500s. The link to research projects and business projects didn’t emerge until about 1916.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also investigates the linguistic history of buses, crowdsourcing, inkling, and pom.

In 1982, Simpson and his colleague Ed Weiner were both promoted to being senior editors, meaning that in addition to their own duties, they were in charge of supervising about 10 assistant editors as they prepared their entries for the dictionary. As the deadline for the final Supplement approached, they realized their teams needed to submit about 125 entries/week. They also realized that they couldn’t rewrite each entry to suit the way they’d write each one; they’d need to fix anything that was wrong with the entries and otherwise leave each as is. In addition, they wrote their own entries and handled several other duties that kept them busy. “At the time, I couldn’t imagine doing anything that was as much fun as doing this” (p. 89).

Once he felt he had things in hand, he was given an additional assignment: serve as chief editor for OUP’s newly contracted Australian National Dictionary. Though he wasn’t thrilled to have the extra work, he came to enjoy it, as well, learning how Australian English had been formed, from the 1770s to the present.

“Each time I thought I’d finally learnt how to be a lexicographer, I found that there was more to learn and new problems to solve. . . . Even though the full dictionary was becoming antiquated, it was still our dictionary of record, and adding new material to it was a privilege. . . . The work, I discovered, was fascinating, and presented problems of the sort I liked solving” (p. 95).

5 Uneasy Skanking, 97–127

In 1986, the fourth — and final — volume of the Supplement to the OED was published. John Simpson and Ed Weiner both hoped the OUP might consider the complete overhaul of the entire OED, though they realized that the prospects of OUP doing so were pretty slim.

Meanwhile, the chief editor assigned Simpson to the “New Words” group, overseeing a team of editors responsible for gathering evidence of new words entering the English language. Simpson found this assignment beneficial not only for its monitoring of the influx of new words, but also for seeing how to organize an OED project in its totality. As chief of the group, he could determine where and how to look for new words, what resources to use, and so on. Once a new word was detected, he urged the volunteer “readers” to use a variety of kinds of resources for finding the word in other contexts. Even supermarkets and menus could be helpful resources for finding new words — such as foodstuffs arriving on shelves or on restaurant tables from round the world.

Microbiologist and chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) not only gave us life-saving pasteurization, but also the coinage aerobic (aero-, “air”; -bic, bio, “life”). Well, actually, he was French, so he gave us aerobie, in a French journal in 1863; English scientists Anglicized it to aerobic in 1865, which sounds more English. Even the English version didn’t get popular attention for another century or so, though.

Though Simpson had a lot of sway over how the editors and the “readers” found words and defined them, there was actually little guesswork about how words were chosen. Any words being considered “had to have existed over several years . . . ; had to be documented in various genres (formal, technical, everyday, slang) [for the most part]; and had to be evidenced by at least five documentary examples in our card files. If a term passed these tests, then it might find its way on to the editorial conveyor belt” (p. 104).

Simpson gives numerous examples of the words his group added during the 1980s, as well as numerous reasons why OED should be slow to add words. Some words were flashes in the pan and disappeared almost as soon as they had appeared. Other words stuck, but they changed slightly or more than slightly in their meaning, their contexts, and so on. It was unwise to add a new word until it “had a chance to settle down in the language” (p. 107). It also didn’t hurt to monitor how other dictionaries were treating the possible new addition. OED is a historical dictionary, not a trend setter.

Another observation by Simpson is that far less than 1% of apparently new English words are actually completely new. The vast majority have existing ancestors already in the language, or at least strong associations with existing words. What’s more, though English has greatly benefitted from “borrowing” words from other languages in the past, nowadays, we “borrow” <10% of the new words that enter English. According to Simpson, as the English language has gained prominence — as have the American and British nations — our language has been more likely to give new words to other languages than to receive them.

Rather than borrowing, English speakers are more likely to create new compound words (e.g., snowboard) or to add affixes (prefixes or suffixes, e.g., microbrewery, selfie). Words can also change in meaning, even if not in form. For instance, think about all the uses for mouse, table, screen. Words can also be changed by converting them from one part of speech to another; for instance, some people bristle when they hear the noun impact being used as a verb, impact (though OED notes its use as a verb dating to 1601).

Still other words are shortened (e.g., microdisk became disk), and others are blended (e.g., influenza + affluence = affluenza). Acronyms such as AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) and laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) are pronounced as entire words, without pronouncing each letter. Initialisms such as FYI (for your information) are pronounced letter by letter.

Simpson notes that the areas of language most likely to produce new words are those areas where there is the most change at the time: science, medicine, slang, global concerns such as environmental threats, politics, and so on. OED does not, however, include proper nouns for people’s names or for geographical locations. The exception would be a word that originated as a person’s name or geographical location but has been adapted to serve other purposes. For instances, wellies, aka Wellington boots, no longer conjure the deceased duke.

Simpson offers a peek behind the scenes to see how the word AIDS (coined in 1982) was added to the OED in the 1980s and how it was updated subsequently, in light not only of new information, but also of new attitudes. During the process of adding new words, Simpson came to appreciate “that it is preferable to document the language from everyday sources . . . rather than from the classic authors” (p. 125). This was also in keeping with how history is viewed differently now than in the past. Rather than focusing on monarchs, wars, and political schemes, history focuses more now on “what everyday life felt like for the ordinary person” (p. 125).

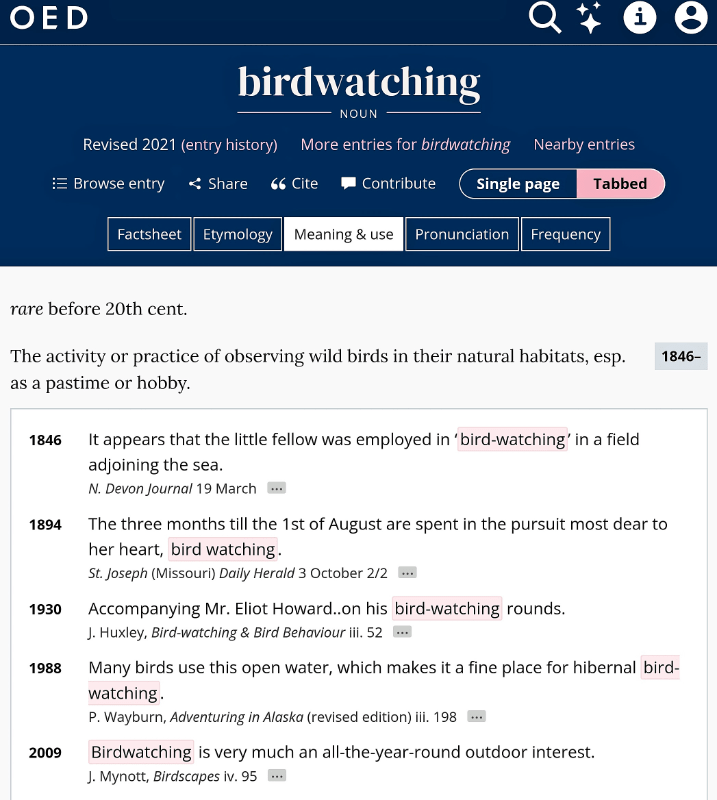

In Simpson’s 2016 book, he noted that the earliest known use of the term was in 1901, when Edmund Selous’s Bird Watching book was published. In the OED online, however, which was revised in 2021, the earliest known use is now 1846, mentioned in a journal. Simpson unwittingly showed why dictionaries need to be updated frequently. Even so, Simpson correctly noted that we now attach “-watching” to many observations and activities, such as “people-watching,” “whale-watching,” “weight-watching.”

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also explores the linguistic history of aerobics, mole, and American.

By the mid-1980s, though Simpson continued to relish his work, he was getting increasingly impatient with simply updating the OED around the edges, rather than digging in and giving it a major overhaul.

6 Shark-infested Waters, 129–145

Up until 1982 neither the OED staff nor the OUP folks had said much — or perhaps thought much — about putting the OED into a computer-accessible format. Richard Charkin, new head of the reference section at OUP, brought new ideas. In his view, computerization would obviate the need for intermittent printed — and expensive — supplements to the OED. In addition, the availability of a CD-ROM containing the entire OED meant that more users might buy it and use it. It could be easily accessed by people who formerly had to trudge to the local or university library to view the OED.

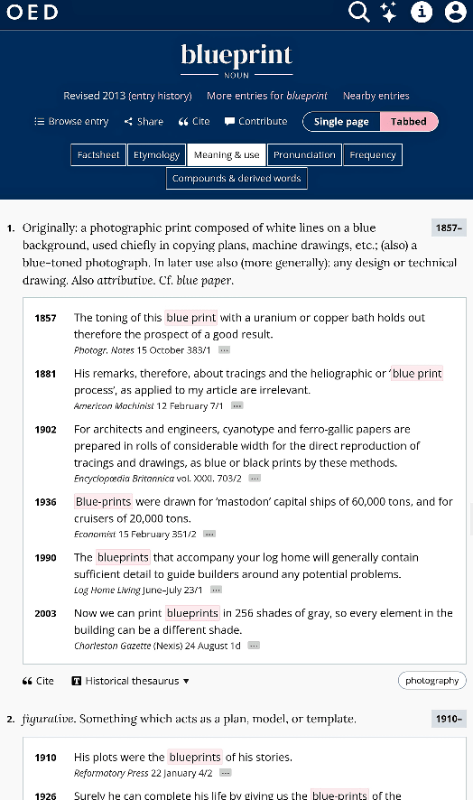

Some kind of pilot project would be needed to figure out whether — and how — to piece together the OED and its supplements into a cohesive whole. Simpson and his former trainer, Lesley Brown, were asked to literally cut and paste entries from the OED and its supplements. Simpson and Brown produced many cut-and-pasted pages, which could serve as a blueprint for how a computer might automate the process. They then returned to their other duties (Simpson with new words, Brown with an abbreviated version of the OED).

Blueprint first entered English about 1857, when it literally meant a photographic print using white lines on a blue background, a compound of blue and print. The first blueprints used paper immersed in photosensitive chemicals that turn blue when exposed to light. A user would draw the map or diagram on it (indoors), then put the blueprint outside in the sun, to generate the image. The figurative use of “blueprint” is known to have appeared in 1910. I’m guessing that people were using it figuratively before then, but not in published printed materials.

While Simpson and the other OED editors were continuing with their various OED projects, Charkin was lobbying the OUP to undertake the computerization of the OED — and meeting a great deal of resistance. As Charkin wore down the resistance, the OUP proposed creating two computerized files: one database for the existing OED and one for the four Supplement volumes. Once both databases were complete, entries could be tagged with their contents (definitions, etymologies, pronunciations, citations, etc.), and the two databases could be merged by computer. Once this was decided, Simpson’s colleague Ed Weiner was invited to join the OUP discussions about the computerization project.

One thing that emerged from these discussions was that the iterative structure and organization of the OED would work well to form the structure and organization of a computerized database. Whew! Simpson would also contribute 5,000 new words/entries to the computerized OED database, updating it. Simpson hoped that the idea of updating the computerized OED might lead to a complete update, but that was not the plan at the time. Charkin suggested a more extensive update by changing the pronunciation system from Murray’s original idiosyncratic symbols to a global standard, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

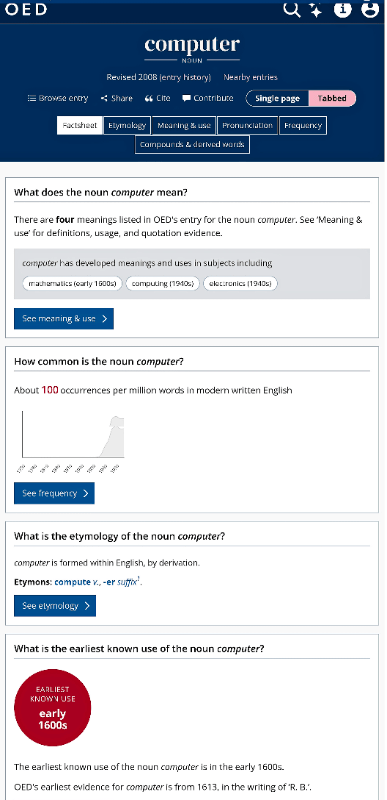

When computer first appeared in English, in 1613, a computer was a person who made calculations or other computations. That meaning was still quite common in 1943. By 1869, computer might also refer to a slide rule or other device used for making calculations. In 1946, it started describing electronic calculation and computation devices. And the rest is history.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also enlightens readers about the linguistic history of inferno.

The OED editors were delighted by the prospect of computerization, not only for the ease of updating the dictionary in the future, but also for their own (and users’) ability to instantaneously search the entire dictionary for any information regarding any words. Almost a dizzyingly delightful prospect.

At the time Simpson’s book was published (2016), the OED listed 1,011 entries ending in -ology (related to logos, Greek for “word” or perhaps “reason” and later, “field of study”) and 508 entries ending in -ography (originally Greek, referring either to styles or processes of putting ink on paper, e.g., calligraphy, photography, lithography; or “names of descriptive sciences,” e.g., geography, bibliography).

The OUP, realizing that it had zero expertise in creating computer databases and always in need of extra funds, put out the word that it sought partners in its new venture. North America came through. IBM offered OUP both equipment and personnel; International Computaprint Corporation (ICC) “undertook to have the whole text of the multi-volume dictionary keyed on to a computer”; and Canada’s University of Waterloo was willing to take on figuring out the most efficient sort of electronic database to use for holding the massive amount of information contained in the OED. Rather than being daunted by the 67,000,000 characters in the OED, these partners were attracted to the challenge.

By the end of 1984, OUP gave its official okay to computerize the entire OED and appointed a project director and designated a budget. Simpson took a night course in computer science at Oxford. Even so, until the late 1980s, many of the books printed by the OUP came off its own ginormous printing presses. After the presses stopped running, OUP decided to unceremoniously recycle the heavy copper printing plates from the OED and other works. By the time Simpson and Weiner stopped the destruction, many of the old OED plates had been destroyed. The remainders were sold through the OUP’s bookshop. The end of a very long era. With the computerization project, “at last, there was a chance that the dictionary might just pull through” with support from the OUP.

7 OED Redux, 147–178

In 1984, OUP told the OED staff that they’d need to publish the Second Edition of the OED in 1989 — just 5 years away! Working with their three North American partners, they’d need to merge the dictionary database with the supplement database into a seamless whole, along with the 5,000 additional new words, and to edit them into publication-worthy text. No one had ever managed such an enormous database merger before. The huge singular database would be edited and used to produce a print version. Next, the whole thing would be adapted to the CD-ROM format.

For Simpson, a key advantage to the computerization project was the possibility for updating the entire OED as a whole, rather than the piecemeal updates that appeared in the Supplements. For Simpson (and his colleagues), computerization was Phase 1; Phase 2 was the dream of producing a wholly updated OED, which could be searched not just alphabetically by single words, but in myriad ways. It would be “a massive, dynamic, and updatable resource” (p. 150), but first things first.

A few consultants to the computerization process had suggested scanning the text, using OCR (optical character reader) software, rather than rekeying it. OED staffers were skeptical but offered some sample pages of the OED for the consultants to use. “Curiously, we never saw any of them again” (p. 152).

Instead, the entire text was keyboarded, with the exacting standards of no more than 7 errors per 10,000 keystrokes. Astonishingly, the human typists met those standards. To add further challenge to the task, many of the quotations being rekeyed were from Old English, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and so on — not text the North American typists were familiar with reading. In addition, the typists added specific tags for each type of element of text (definition, etymology, pronunciation, etc.). Once the text was typed and tagged, it went back to the OED staff for proofreading, with the aid of about 50 freelance proofreaders. And all of this was happening with tight deadlines.

For a time, Simpson, his wife Hilary, and his daughter Kate were invited to Waterloo. He was to confer with the Waterloo database wizards and computational logicians, as well as to offer postgraduate classes on lexicography in the university’s English Department. Simpson and his students also had access to the OED database as it existed at the time. Meanwhile, Hilary taught Waterloo students about the modern English novel, and Kate attended child care nearby.

Among the many snags in creating the dictionary database was how to handle chronologies when a date was given as “circa” — in recent times, “circa” might mean just a few years; a century earlier, it might mean a range of 25 years; in the early history of the English language, “circa” might mean 50–100 years or more. Simpson and the Waterloo wizards had to come up with specific ranges of years for each use of “circa,” so the entries could be ordered chronologically.

While with the database wizards, Simpson got a taste of the possibilities offered by having a searchable database. Database analysis could readily detect that Shakespeare had added about 8,000 new words to the English language, including about 2,900 nouns, 2,350 adjectives, 2,250 verbs, 146 phrases, 40 interjections, and 39 prepositions. The analysis could even figure out whether he coined more words during his early writing or in his later writing, as well as how many English words were coined overall during those periods.

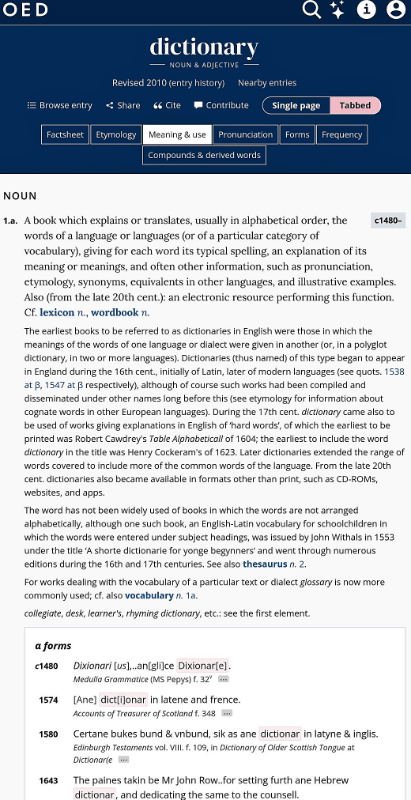

When the word dictionary first emerged, it typically referred to a bilingual dictionary, listing words in one language (e.g., Latin) and showing the meanings of those words in a second language (e.g., English). Though OED’s earliest written evidence for its use is about 1480, it’s thought to have been in use even earlier, during the period 1150–1500. Robert Cawdrey, a schoolmaster, is credited with writing the first dictionary written in English, published in 1604; it actually listed mostly “hard” words, with Latin or Greek origins. The first true English dictionary wasn’t published until Dr. Samuel Johnson produced his two-volume 1755 dictionary. Across the pond, Noah Webster published his two-volume An American Dictionary of the English Language in 1828.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also illustrates the linguistic history of redux, same, transpire, guru, hue and cry, brick wall, and cham (also nickname for groundbreaking lexicographer Samuel Johnson).

Simpson makes it a point to say that unusual, antiquated, peculiar words do belong in the dictionary, but they’re “not central to the real language” on which the dictionary should focus its attention. Simpson was especially excited about the possibilities offered by a searchable dictionary that could trace how word changes correlated with societal changes, how the frequency of particular words’ usage rose or fell over time, how historical events affected the language, and so on. Which words are borrowed, from where, and when?

On returning to Oxford from Waterloo, Simpson was appointed co-editor of the computerized OED, with his colleague Ed Weiner. Though it meant more work for him, his “trepidation was outweighed by the thrill of having a major role in breathing new life into the Victorian dictionary” (p. 171). It had taken 18 months to keyboard the original OED and all the Supplements and an additional 6 months for the co-editors to proof all of the entries once more. Weiner and Simpson each read 10 volumes of the rekeyed text, which was to become the 20-volume Second Edition of the OED.

The next big task was to integrate these databases into an intertwined alphabetical dictionary. Some integration steps were easier than others. For instance, suppose that the original OED for an entry word listed senses 1, 2, and 3; and one of the Supplements addressed a new sense 2, which should nudge previous senses 2 and 3 to 3 and 4. That could also be managed, but other aspects of integration required the OED staffers to manually integrate some aspects of some entries. The 1989 deadline was fast approaching.

8 The Tunnel and the Vision, 179–208

March 30, 1989, OUP launched the Second Edition of the OED in 20 printed volumes. The event was preceded and followed by plenty of publicity, during which Ed Weiner often held aloft a CD-ROM, hinting of the to-be-published computer-accessible OED-2. The first printing of the OED-2 sold out within months — mostly to university libraries around the world, perhaps aided by Weiner and Simpson’s tours of North America and Japan.

Weiner and Simpson returned from their tours reinvigorated to pursue their aim of overhauling the entire OED. The OUP, however, was ready to shift their priorities from the OED to all the other projects that had been neglected during the push to complete OED-2. Acknowledging the current situation, the two co-editors returned their attention to the stream of new words emerging into the English language.

While monitoring this stream, Simpson realized that “more English was spoken outside than inside Britain. . . . if we really wanted to capture the changing face of English more widely, . . . we needed a stronger presence in America” (p. 195). In fact, “most language change was taking place in American English” (p. 196). In addition to this lexical vigor of North America, technology there was light years ahead of that in Great Britain, and it offered the largest market and greatest support for the OED.

That year, the OED set up a “reading programme” in the United States, directed by an American poet and OED enthusiast, Jeffery Triggs. Triggs asked his “readers” to submit their citations electronically, effectively ending the old OED tradition of submitting citations on index cards. Though the existing index cards are still available on site, most citations are now solely in digitized format. Simpson noted that the physical cards were easier to manipulate, sort, fan, select, and sequence, compared with on-screen citations that can scroll off the screen in either direction. The advantages of digital searchability, access, and ease of editing can’t be discounted, though. In fact, every single word in every citation can be searched. Triggs regularly transmitted to the OED offices the digitized citations he received.

The changes Simpson and Weiner had in mind: rethink the definitions; update the quotation sections; reconsider the very structure of entries; fix references to outdated currency, geographical names, and so on; in addition to birth years, add death years to some etymologies; reconsider label names; and add many more new words, as well as new word meanings. This required a complete overhaul, not just a few tweaks. One problem: No funding from the OUP for this monumental task.

Luckily, scholars were pining for the kind of OED that Simpson and Weiner wanted to produce. Worldwide, researchers were seeking what Simpson and Weiner were hoping to create — at first just a few, but more and more over time.

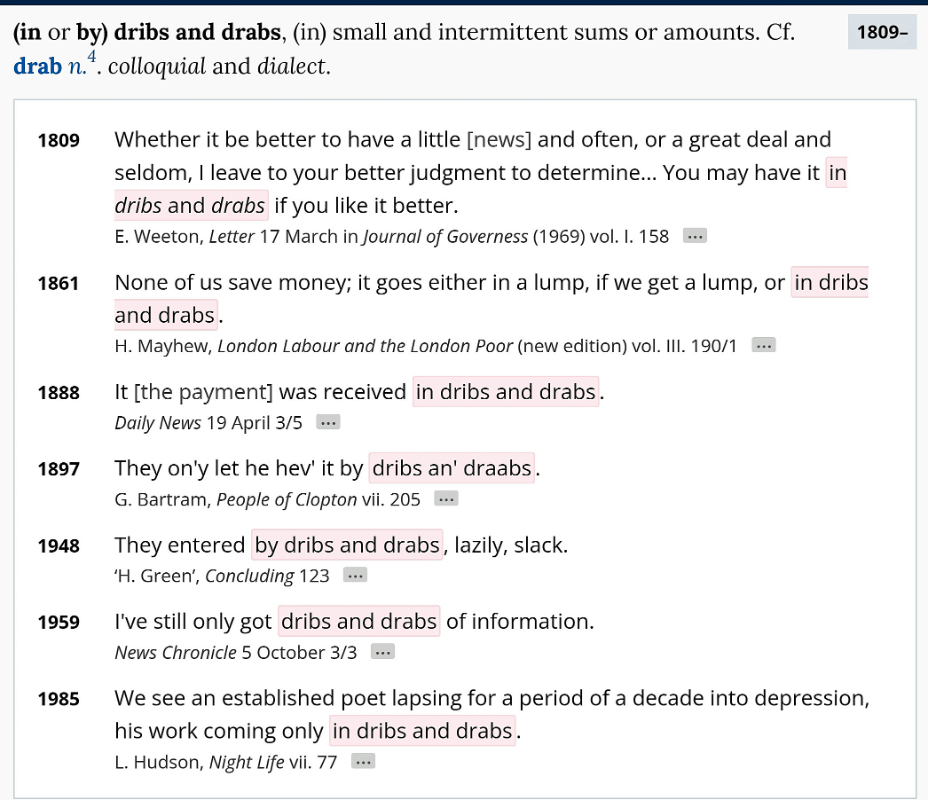

The solitary word drib originated in the 1730 Scottish word for “droplet.” The original OED didn’t include the phrase dribs and drabs; it wasn’t included in the OED until 1993, which found a first known occurrence dated back to 1809.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also reviews the linguistic history of launch, disability, and burpee.

A pilot project using the database at Waterloo revealed some of the flaws in the existing OED quotations — few women authors, few American authors, too many Victorian authors, and so on. The pilot study offered tempting possibilities of what could be done if the OED were fully searchable on computer (on CD-ROM; online options weren’t yet considered). Simpson spent several pages exploring just some of the many possibilities.

9 Gxddbov Xxkxzt Pg Ifmk, 209–237

By 1993, Weiner and Simpson were ready to campaign the OUP folks to go along with funding the complete overhaul (and further computerization) of the OED. They were aided in this campaign by some of the senior professors of Oxford University who were “Delegates of the University Press, that body of professors ultimately responsible for approving the Press’s academic publishing policy” (p. 210). Later that year, the OED director and editors were invited to sketch out a project plan. Ideally, such a plan would show project completion in 2000, with a feasible budget reflecting this speedy schedule.

To come up with a plan, they needed a detailed editorial policy, along with yearly estimates for what needed to be done by what date: 414,800 word entries, divided by 7 years (1993–2000). A seemingly impossible task, but their only hope for getting approval to proceed. The OUP gave them the go-ahead, on condition that the director and the co-editors (Simpson and Weiner) meet regularly with OUP representatives (e.g., professors of sociolinguistics, philology, English literature), forming the OED Advisory Committee.

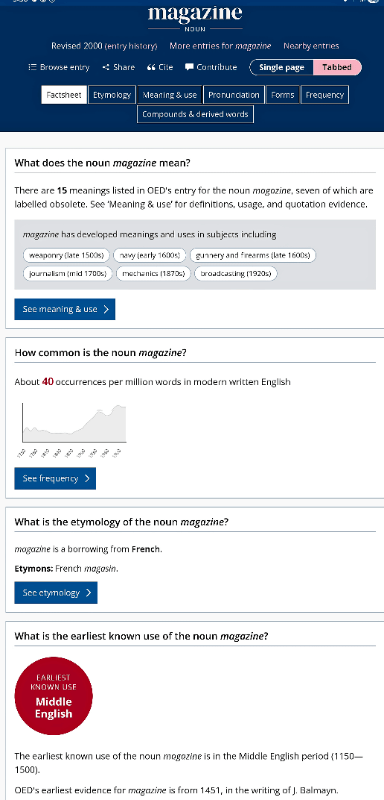

Though the earliest uses of magazine appeared in Middle English (from Middle French), it wasn’t known to refer to a print publication until 1731. Previously, it more commonly referred to a “storehouse for goods or merchandise.”

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also studies the linguistic history of vet (short for veterinarian) and subfusc (dark gray color).

Right away, the Advisory Committee agreed that a complete overhaul did not mean overhauling the basic structure of the dictionary (alphabetical and historical) or of its entries (e.g., definitions, etymologies, quotations). That could and must stand. They also agreed that the senses and subsenses of meanings would continue to be organized historically, not in terms of frequency of use. Other dictionaries prioritize frequency of use, but not the historically based OED. And no one was receptive to the idea of omitting words that were now obsolete. The OED offers a complete history of the English language, not just a contemporary history. All agreed that the “principle objective was to illustrate—through the dictionary—the complex emergence and flowering of English as a major world language” (p. 215). And, of course, the dictionary’s entries were to be based on documentary evidence, not subjective impressions.

“English is called a Germanic language because it was brought to the British Isles by Germanic invaders and settlers (northern European tribes) speaking Germanic dialects—from an area much larger than Germany today” (p. 215). “Even today, words of Germanic origin dominate large areas of our basic vocabulary: the number system; most of the short prepositions and conjunctions we use; the basic verbs be, can, do, have, may, must; the ‘strong verbs’ which change their stem vowel in the past tense (swim/swam, ride/rode)—in fact, out of a list of the [100] most frequently used words in English today, [98%] are of Germanic origin” (p. 216). Not until the Norman Conquest of 1066 did French and other romance languages richly broaden the English language. “The OED tells us that we have two and a half words of Romance origin in English today for every word of Germanic, but . . . those Germanic words are still often the big-hitting, high-frequency ones” (p. 216).

Though the plan for the new OED was to conserve much of the structure and approach of the OED’s past, all were agreed that the new OED needed to greatly broaden the reach of the texts chosen for the citations. The classic authors wouldn’t be eliminated, but they’d be bolstered by a much wider selection of printed materials, by a greater diversity of authors. When documenting the full English language, the OED needed to document how most English speakers use the language, not just the words of the literary giants. When drafting the original OED, James Murray was heavily criticized for using newspapers, as well as literature; his successors would broaden this reach even further.

After two years of progress and of committee meetings, Simpson and Weiner were asked to produce a study showing their progress to date. Luckily, the committee approved the study and recommended to the OUP that it fund “the full-scale updating and revision of the dictionary” (p. 225).

On pages 226–236, Simpson amply illustrates how the OED staffers fully updated and revised the dictionary by detailing how they did so with the word “fuck.” “The updated entry differs from the old one very considerably . . . . The definitions were no longer shrouded in Victorian reserve, abbreviations were expanded, and more standardisation was introduced at many levels; the etymology brought in the latest information from other scholarly sources . . . and tried to explain the progression of meaning before the term entered English. . . the quotations were found in a far broader range of sources than previously, and were tracked back to their first editions . . . not using corrupted secondary data . . . and the range of informal expressions was extended to cover more of the real language with which English speakers are familiar” (p. 237).

10 At the Top of the Crazy Tree, 239–261

At some point in 1993, Weiner told Simpson that he really preferred just to work on the dictionary, not to co-lead a team as chief editor. Would Simpson please take on the full responsibility as chief editor? With Weiner as his deputy, Simpson took charge, converting the project plan into action, establishing milestones, objectives, and work pace, as well as editorial standards. It didn’t change the relationship between Weiner and Simpson, but it did mean that Simpson was the face of the OED to the OUP, to Oxford University, and to the wider world off campus.

In 1994, the OUP had approved the funding of the Third Edition of the OED — with a deadline of 2000, just 6 years hence. The OED staff would have to recruit more lexicographers if they were to have a chance of meeting the deadline. They were able to recruit some historical-dictionary editors from other OED departments, but not all experienced OED lexicographers were enthusiastic about such a monumental undertaking. Even after adding many of those, the project still needed more staffers.

They wanted to reach out to possible prospects, but they didn’t want to cast such a large net that they’d spend weeks screening obvious misfits for the job. Just having a love for words doesn’t suffice. “Out of every [500] applicants, only around [2] would be any use to us” (p. 245). They quickly developed some handy screening techniques (no overlong letters, no misspellings, no sloppy notes, etc.). Then they narrowed the group of those left standing to about 30.

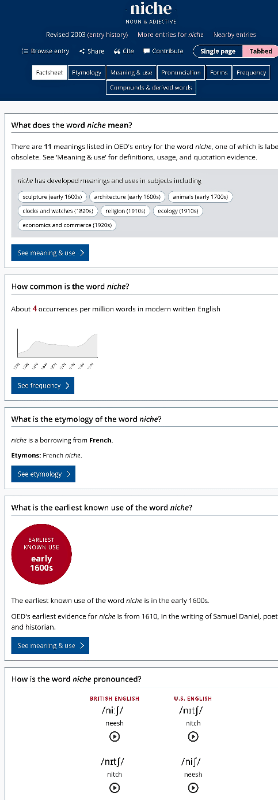

When niche first entered English, in 1610, it referred to a physical recess or hollow, into which a decorative object was placed. It wasn’t known to have a figurative meaning until 1733. Both “nitch” and “neesh” pronunciations are widely used, though “neesh” seems to be gaining in frequency.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also highlights the linguistic history of bugbear and hone.

They gave those 30 applicants an aptitude test, which was intended to reveal their ability to create entries for a historical dictionary. Only about 20 submitted a completed test. Among those who completed the test, the OED staff chose about 5–6 to interview. Clearly, these candidates had shown that they had stamina, a key characteristic of a lexicographer. At that point, a consideration was not only competence, but also compatibility. Would each candidate fit in with the existing team? Also, how well did they tolerate criticism? Lexicographers must be able to handle criticism deftly, to learn from it, and to move forward.

Since 1983, the public face of the OED used OWLS — Oxford Word and Language Service. Questions from the public were answered by staffers via OWLS. The answers offered by the OWLS staffers were welcomed by the public, who often sent thank-you notes in response.

In previous chapters, Simpson had occasionally briefly discussed his wife Hilary, his older daughter Kate, and his younger daughter Ellie, who is severely disabled. In this chapter, he describes more fully the impact of this disability on all members of the family.

11 Shenanigans Online, 263–292

When it comes to pronunciation, vowels are far more problematic than consonants. “They are volatile elements in the periodic table of the alphabet” (p. 263). Simpson has many opinions about other letters, too: B shows “battering aggression”; C “is calmer”; D “is explosive”; and so on. Simpson also notes that Ammon Shea attributes “the characters of the letters of the alphabet . . . in my favourite book about the OED: Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages” (published in 2008). The team started at the letter M, rather than A. They reasoned that the earlier material would be more of a challenge because the original editors of the OED hadn’t quite developed their style and structure in those early volumes, starting with A. They proceeded from M through R, returned to A through L, then finished with S through Z.

Once the OUP dispensed with their ginormous printing presses, that area offered space for the OED staff. Their task now: “Work through the entire text of the OED, updating all aspects of each entry (many of which were unchanged since the Victorian period) according to the best information available to modern scholarship” (p. 265).

As 2000 approached, the due date was pushed back to 2005 . . . and then to 2010. In fact, as Simpson saw it, the OED would be perennially updated, so a particular target date was almost meaningless. Or so he hoped.

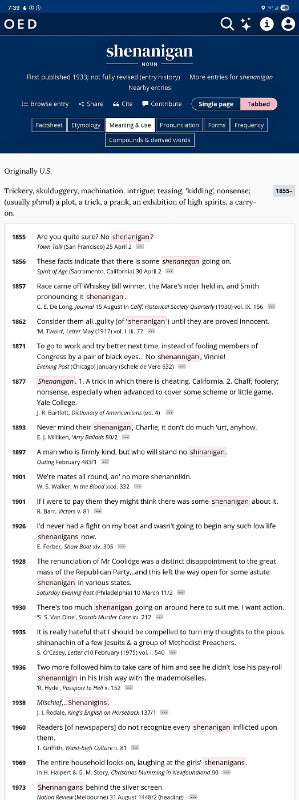

When shenanigan first entered English in 1855, in the United States, it was used in the singular, not the plural form. In fact, it wasn’t until 1926, when Edna Ferber used shenanigans in a novel, that the plural form was first used in print. In the 1950s, my mother often suspected that I was up to more than one shenanigan and cautioned me against doing so.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also offers insight into the linguistic history of online.

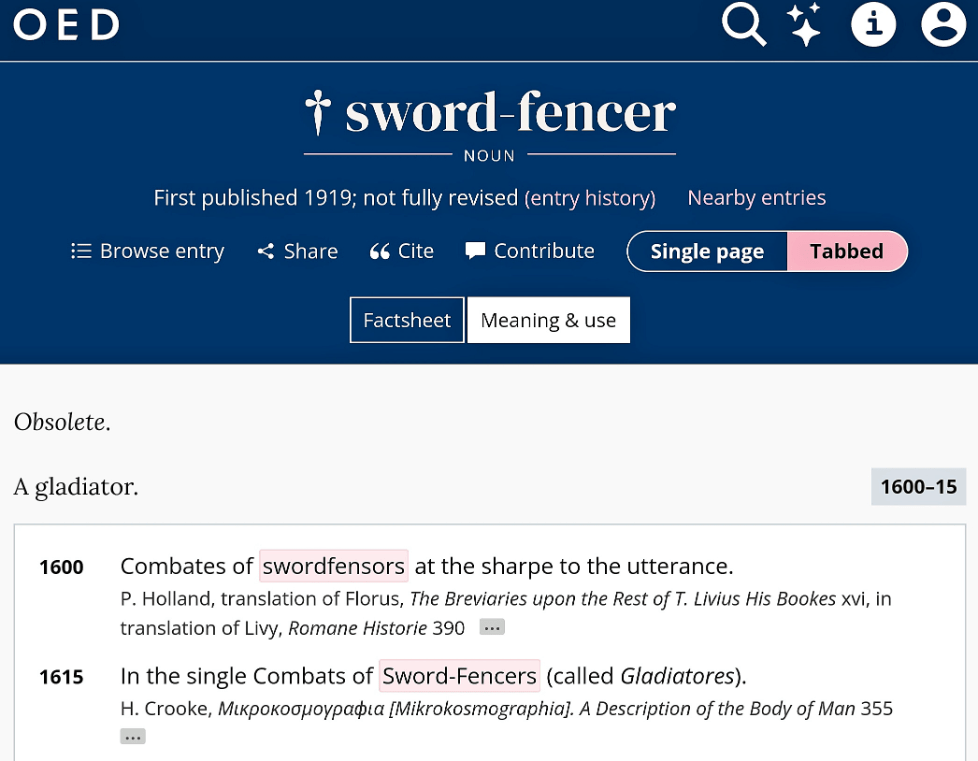

Recall that in Chapter 9, Simpson and the Advisory Committee had decided to keep all words, even obsolete words. Nonetheless, they felt that readers deserved some indication that a word was obsolete. They settled on the dagger († — aka “obelisk”) symbol to alert readers to words for which there was no documentary evidence of their usage for more than 100 years.

As you can see, OED has flagged sword-fencer as obsolete, having not appeared in print (other than in the OED) since the early 1600s. If it starts cropping up again, the OED will quietly remove the dagger and the “obsolete” designation. Feel free to start liberally sprinkling sword-fencer in your writings, and perhaps you can help de-obsolesce this vivid word. By the way, de-obsolesce doesn’t yet appear in the OED. Perhaps we should start sprinkling it about, too?

Another peculiarity arose in regard to some scientific vocabulary. In general, lexicographers prefer to write concise definitions using everyday language. However, some scientific terms require additional explanation. Lexicographers usually handle this challenge by starting the definition with a simpler, more commonplace definition, which they then amplify with a more detailed scientific definition, which scientists in that field of study would understand.

As the OED project was proceeding, the world outside the OED offices was moving increasingly to online research availability. This availability further broadened the resources available to the OED staffers. Now, instead of physically walking to the archives of index-card citations, or to the books in the extensive reference library, or even flipping through the pages of the OED-2 (available on CD-ROM since 1992), lexicographers could do at least some of the research sitting at their desks and conducting online research. The proportion of desktop research continued to increase over time, as more and more databases came online.

In 2004, Google Books started “offering lexicographers new worlds of words to search through; Britain fought back in 2007” with their own online databases. Because scanners and scanner software was often flawed, these databases could be flawed, too, and “databases soon started offering links to facsimile versions of the documents they had scanned.” That addressed the accuracy problem, but not the searchability issue. If the database’s text is garbled, search tools are inadequate.

To address some of the issues with online databases while reaping the benefits of their use, the OED staff developed a hybrid system, using both their old cards and the new online information. The “readers” who submit citations also benefit from access to these databases, while using their own human analytic skills to distinguish nuances of meaning. In addition, the editors knew that alert users of the OED would help them to find even earlier citations that they may have missed. Simpson shows how this process might work, regarding the entry hotdog.

Meanwhile, in North America, Jeffery Triggs was trying to write software that would allow OED to be published as a fully searchable online database of the history of the English language. The CD-ROM of OED-2 was a good starting point. Triggs was conferring with Simpson about how to do it, while neither of them informed OUP about their scheme. The duo soon invited Weiner to join them in their plotting. The next OED person invited to join was the business director, who also saw the exciting possibilities. In 1995, Triggs and his co-conspirators had developed a prototype for the online OED. They then ventured to share it with some folks from the OUP and from Oxford — who were not enthused; they couldn’t see any benefit from adding it to their traditional book publishing.

That didn’t dampen the enthusiasm of the co-conspirators. At that time, there were about 500 websites on the Internet. About 14 million people used the Internet then, mostly for email, bulletin boards, and a smidge of e-commerce — compared with the many billions of Internet users now.

Up until about this time, the OED editors were marking up printouts, which were then keyboarded by specialists. With new software capabilities, editors could edit their entries online. This not only saved the editors time, but also saved the OUP money by not having to pay for specialist keyboarders. The editors enjoyed this ability, feeling greater control and satisfaction while producing their entries. To facilitate the online editing, each aspect of an entry (e.g., definitions, etymology, quotations, pronunciations) had a color code, making it easier to visually comprehend the whole structure. Naturally, the newer editors more readily adapted to the new online methods; the older editors who didn’t adapt as easily often didn’t last long after implementation.

Other problems arose, which needed software fixes. For instance, when researching a compound word — tablecloth, table-cloth, table cloth — it was initially necessary to do three separate searches. Someone created a software program that solved this problem, and other researchers soon adopted it, too.

Simpson and his team continued to lobby the OUP to reconsider publishing the OED-3 online. The key selling point was that the OUP would be able to sell the online version, to recoup at least some of its huge investment. Their OED marketing director did some research and found that librarians were itching to buy the OED online. As the new millennium approached, at last, the OUP was behind the OED online. The OUP could start selling subscriptions to it even before all the updates were completed. The OED could be continually updated, incrementally.

In 2000, they went live with the full OED-2, along with the first installment of updated entries — just 1,000 to start, but with more to come. Part of the OUP publicity campaign for the release included John Simpson discussing the dictionary with the 5-year-old grandson of James Murray, OED’s first editor. Needless to say, young Murray charmed the media.

12 Flavour of the Month, 293–328

Since the OED’s first publication in 1884, it had never returned enough revenue to the OUP to defray its cost. That was true of the online OED-2, as well, but at least it was returning a trickle of revenue to the OUP, which was more than had been the case during its development. “Almost every university in the [English-speaking world] was subscribing to the OED Online,” so its future seemed more certain than ever (p. 293).

Once the OED was online, it drove home the realization that language is constantly changing and that new information might change what we know about it. Scholars and other users were sending newer and better evidence about the entries in the OED. These informants were helping the editors to improve the dictionary and the historical record of the English language. Simpson thrived on this “democratic user engagement” (p. 294).

Even with increasing access to online databases and other information, the editors continued to need to do footwork to research some aspects of language. As an example, Simpson traveled to the Herefordshire Record Office to research its printed archives for a deposition offering insight into the 1682 use of the word “pal.” Of course, that degree of footwork can’t be done with all words, but there are still situations for which it’s needed.

In England, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, English is the de facto official language, but not the de jure (legally mandated) language. Canada, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and South Africa have declared English to be the de jure official language. Many European nations balk at the creep of English vocabulary into their own languages.

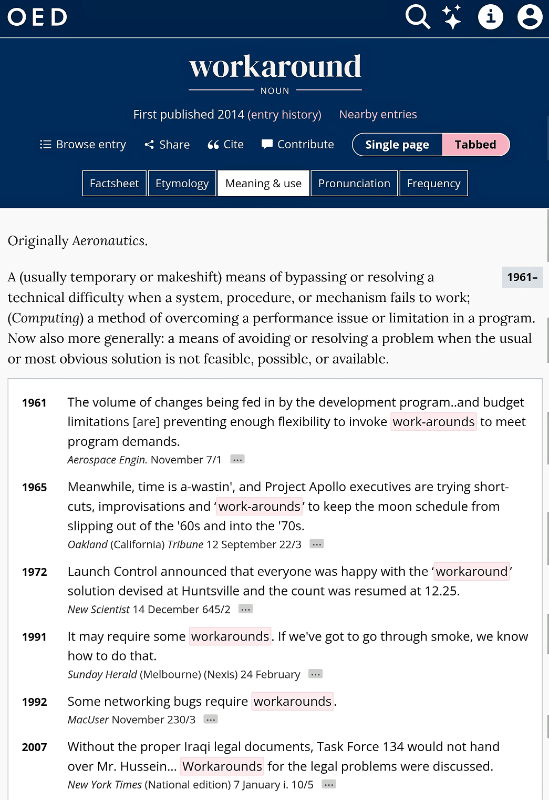

After going online, the OED editors were expected to update and publish at least 1,000 entries every 3 months, but Simpson hoped to bump that up to 2,000–3,000 entries. They continued to proceed alphabetically, not skipping a single word in the alphabetical sequence — if not now, when? As they proceeded into the letter S, they felt their near-obsolete software slowing them down. Their tech folks were continually devising workarounds because the original code wasn’t fixable.

Though word phrases with work have been around since the 1600s, the verb phrase work around didn’t appear in print until 1907, and the noun workaround didn’t show up until 1961, mostly to do with aeronautical engineering.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also features the linguistic history of flavour of the month, sorry, long chalk, balderdash, and clue.

In 2005, a brand-new software system was installed, integrating “most aspects of the editorial and publication process and [finally allowing the lexicographers] to edit wherever we wanted in the database” (p. 306). This flexibility led to the 2008 decision to continue with the alphabetical sequence every other quarter, but to address the most meaty, core-vocabulary words in alternate quarters. The meaty words were stressful to edit but meaningful; the alphabetical sequence offered some respite for the editors but weren’t as crucial to users. On pages 308–312, Simpson illustrates how they updated the word gay.

As the OED online gained attention, its media profile was highest in the United States, where Jesse Sheidlower headed a small Manhattan editorial office within the OUP offices there. Sheidlower facilitated the addition of numerous American English entries. In Britain, the BBC orchestrated a word-hunt quiz show involving the OED. It ended up popularizing the OED further and fostering enthusiasm for finding words to submit to the OED. Simpson wanted to extend this enthusiasm by adding images to the OED — “charts, diagrams, animations, and videos that would give them further clues about language history” (p. 321). He wondered whether this could also work with the Historical Thesaurus of the OED, which had started with a pilot project in 1965.

13 Becoming the Past, 329–340

In 2013, when the OED-3 was about 40% of the way toward Z, Simpson decided the OED-3 was well in hand, and it could continue to move forward without him if he retired, turning over the job of chief editor to Michael Proffitt. The end to his time at OED didn’t have to mean the end to his own research and writing, on topics other than entries to the OED.

The concerns of his family also made it a good time to move away from Oxford and toward somewhere that could better accommodate the special needs of his younger daughter, Ellie. His older daughter, Kate, has daughters of her own, and they also visit Ellie.

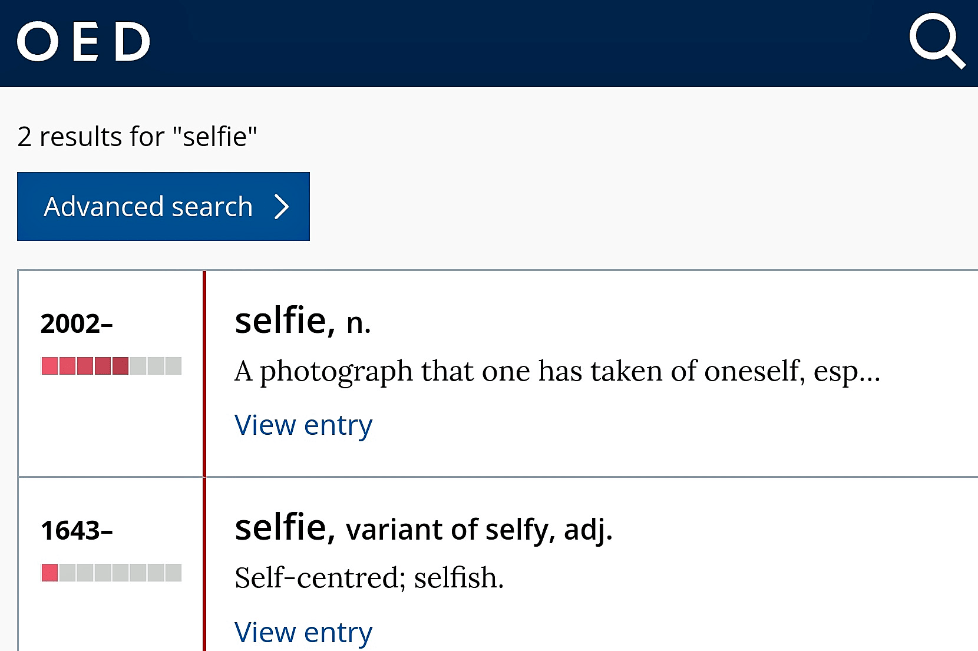

The noun selfie first emerged in the 21st century, with the earliest citation in 2002. The adjective selfie, meaning “selfish” or “self-centered” appeared in the 1600s and is now quite rare.

Note. In this chapter, Simpson also describes the linguistic history of enthusiasm and spa.

The OED is now more accurate, using more and better evidence, and more accessible to more people and a wider variety of people. Simpson agrees with his wife Hilary that he’s “an ordinary bloke who’s been lucky enough to do an extraordinary job” (p. 340).

[Back matter]

Acknowledgements, 341–342

Further Reading: My 100 Favourite Books on the OED, 343–346

Nope. There aren’t 100 books on the OED. Instead, he includes 12 books, a few of which he had mentioned in the body of the text. He has especially kind words for Peter Gilliver’s The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary and Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman (The Surgeon of Crowthorne in Britain) and his The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the OED. As he mentioned previously, his favorite book on the OED is by Ammon Shea, Reading the OED: One Man, One Year, 21,730 Pages (published in 2008).

Index, 347–364

The index highlights in bold the words that featured their history in the text; other featured words are indicated, too, with italics. In addition to subjects, he indicates people and books here, too.

[About the author, 365]

Brief profile with photo

Text by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.

Images of dictionary excerpts, from OED Online, by subscription.

Leave a comment