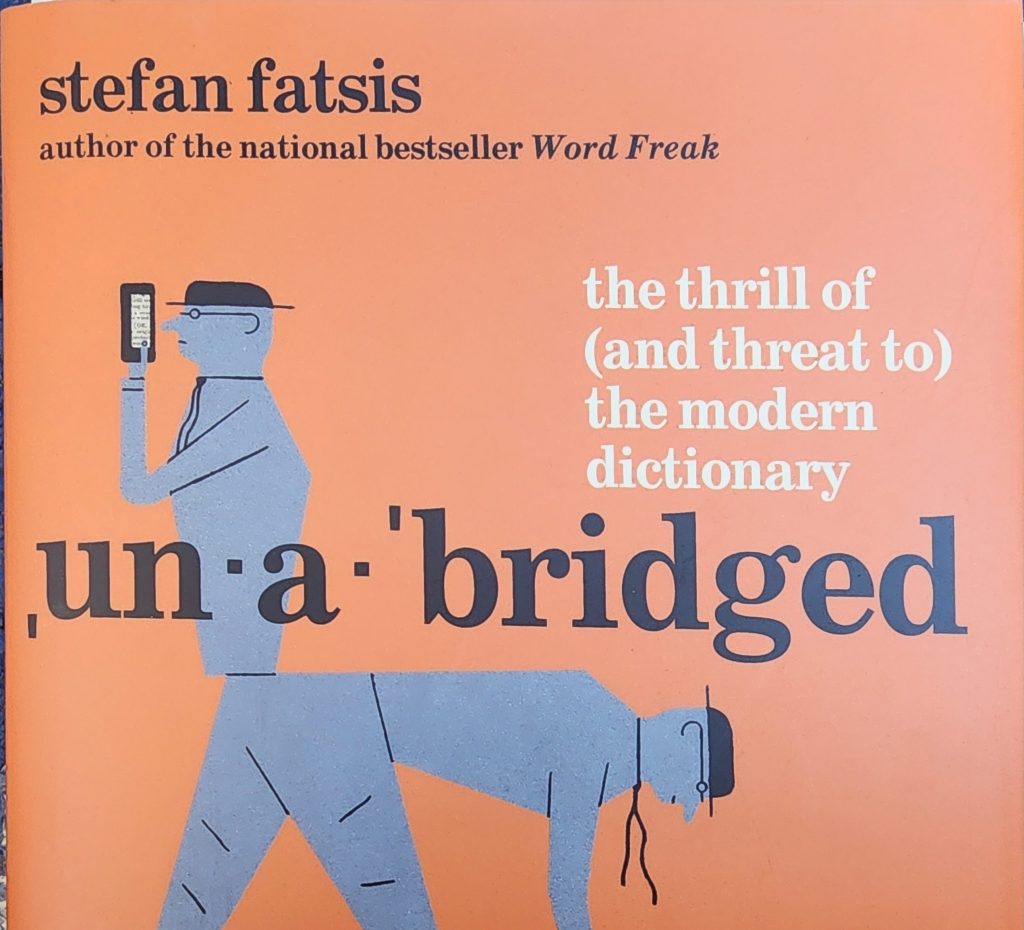

The Thrill of (and Threat to) the Modern Dictionary” by Stefan Fatsis

Fatsis, Stefan (2025). Unabridged: The Thrill of (and Threat to) the Modern Dictionary. New York: Grove Atlantic.

Contents

- Note

- Introduction

- 1 Train

- 2 History

- 3 Business

- 4 Define

- 5 Corpus

- 6 Neologism

- 7 Slip

- 8 Collection

- 9 Slur

- 10 Pronoun

- 11 Entry

- 12 Social Media

- 13 News

- 14 Artificial Intelligence

- 15 Future

- 16 End

- [Back matter]

Note: A Brief Comment or Explanation, ix–xi

“Merriam-Webster Inc. traces its roots to Noah Webster [1758–1843], the American revolutionary, politician, newspaper publisher, writer, author, educator, spelling reformer, . . . lexicographer. . . . All things dictionary in the United States descend from Noah Webster” (p. ix). “Webster published his first dictionary in 1806 and his first major dictionary in 1828,” and the Merriam brothers, George and Charles, acquired rights to that 1828 dictionary after Webster’s death.

In 1890, the first official “unabridged” Merriam-Webster dictionary was published, followed by a second unabridged edition in 1934 and a third unabridged edition in 1961. In the 21st century, the online versions of these dictionaries have gained prominence, though print dictionaries continue to be published; the abridged “Collegiate” dictionary continues to be updated, and new editions are released periodically (e.g., 12th edition, November 18, 2025). An online version of the unabridged dictionary (last updated about 2015) is available by subscription, but the Collegiate dictionary is available free, with advertisements.

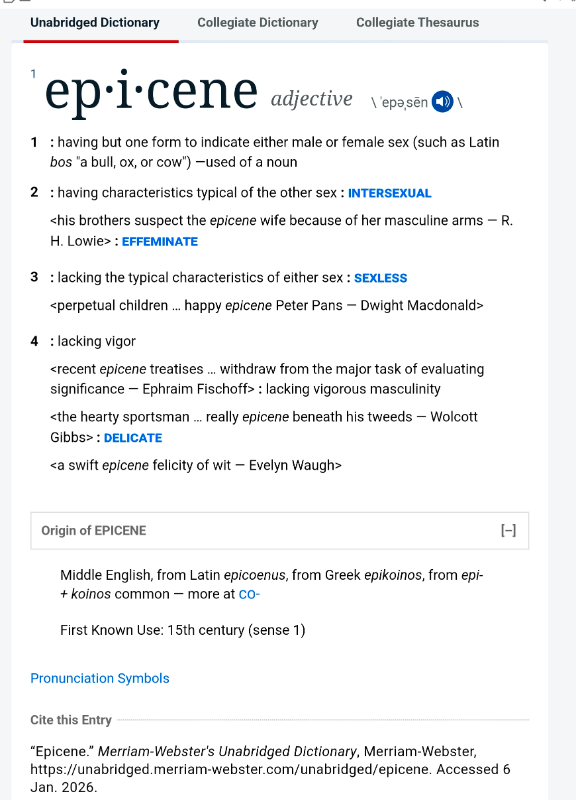

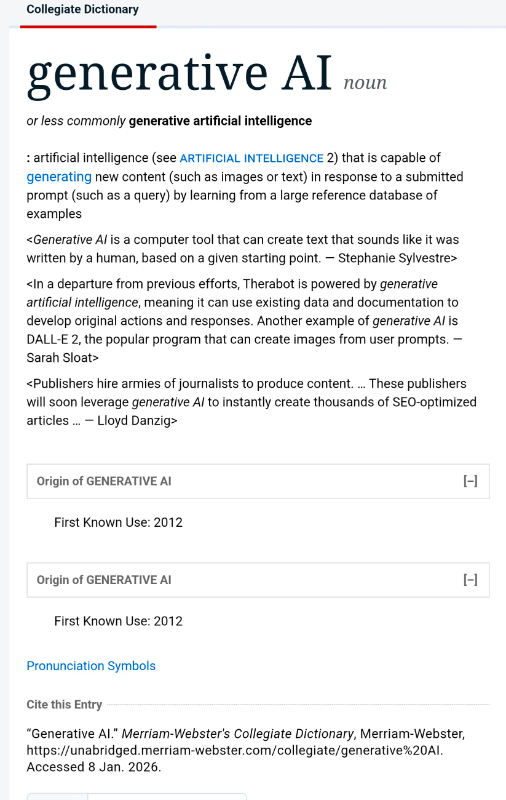

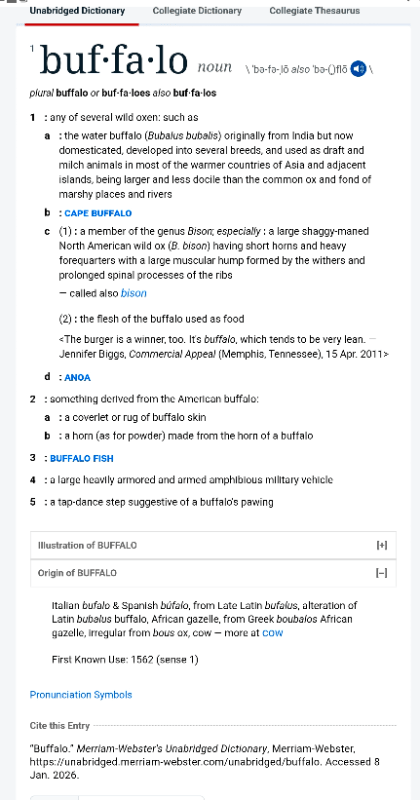

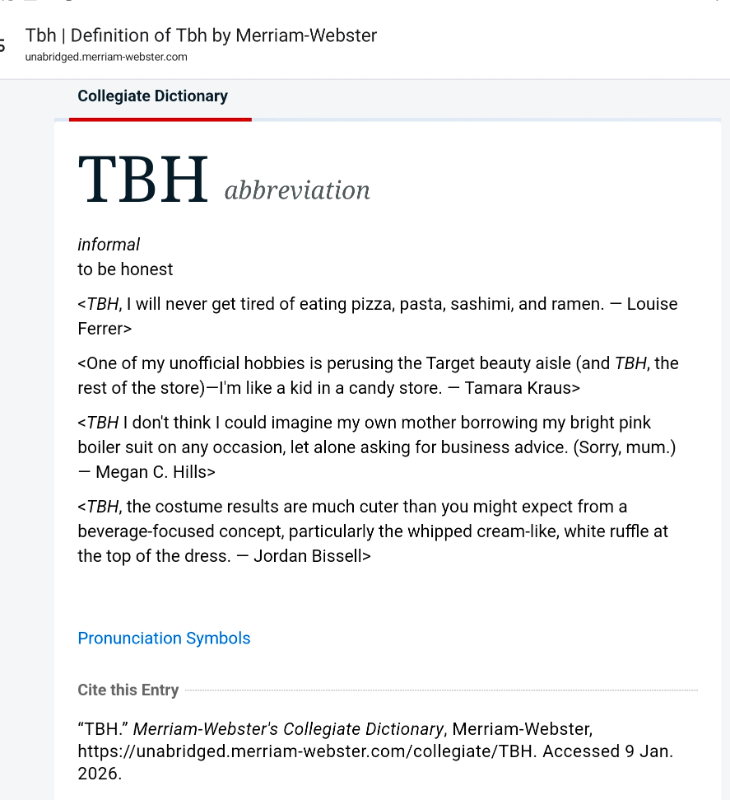

I plan to include at least one dictionary definition for each chapter, typically a word that’s not in my expressive vocabulary. I may recognize and understand it, but I don’t typically use it myself.

Introduction: A Part of a Book or Treatise Preliminary to the Main Portion, 1–10

In this chapter, Fatsis discusses his rapturous love of dictionaries, starting with his receipt of one at age 11 years. Four decades later, he decided to try to visit the Merriam-Webster (M-W) offices and perhaps to write about M-W’s complete overhaul of the Webster’s Third International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged for online access.

Webster’s Third International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged — 4″ thick, 13.5 pounds, >2,700 pages; $47.50 in 1961, listed by Powells Books for $129 new or $45 used in January 2026 (free shipping).

After writing a long article about M-W and the dictionary, Fatsis asked John Morse, then the M-W president and publisher for permission to “stick around as a sort of lexicographer-in-training slash journalist-in-residence to write a book.” Morse said okay and gave him a key to the building. “For the next few years, I researched Merriam’s dusty history and drafted definitions of words that were new or topical or weird or neglected or fun” (p. 2). Fatsis could continue the tradition of making word lists, which Sumerians had been doing in the third millennium b.c.e. Fatsis pointed out Augustinian monk Ambrosius Calepino, who spent 30 years “compiling his 1502 Latin masterpiece, Dictionarium, and went blind doing it” (p. 2).

The earliest dictionaries were aimed at scholars, not the general public (who typically weren’t literate), and were organized by subject matter, not alphabetically. Robert Cawdrey published the first English-language dictionary, his 120-page, 2,500-word A Table Alphabeticall, in 1604 — intended for “Ladies, Gentlewomen, or any other unskilfull persons,” not for scholars. He included simple etymologies but no pronunciation guides or quotation exemplars.

A century and a half later, Samuel Johnson published his landmark 1755 A Dictionary of the English Language. Johnson recognized that a dictionary offers a snapshot of a language that has evolved and will continue to do so. About 5 decades later, Noah Webster published his first dictionary. By the time Fatsis arrived at M-W, the dictionary makers aimed “to identify words that appear consistently in professionally edited media over an unspecified but sustained time; to define them according to a bunch of rules . . . ; and to publish them” (p. 4).

At least by the time of Samuel Johnson, lexicographers had been aware that language constantly undergoes dynamic changes, so dictionaries must constantly be amended, revised, updated, renewed. When dictionaries were published in print form, in order to make room for newly added words, other words needed to be abbreviated or perhaps eliminated altogether. Special features such as biographical or geographical lists were also cut to make room for new additions. (In 1961, Webster’s Third, Unabridged, included about 465,000 words; M-W’s 2003 Collegiate included about 165,000 words.) Even “unabridged” dictionaries had to be “abridged” somehow to make room for new words.

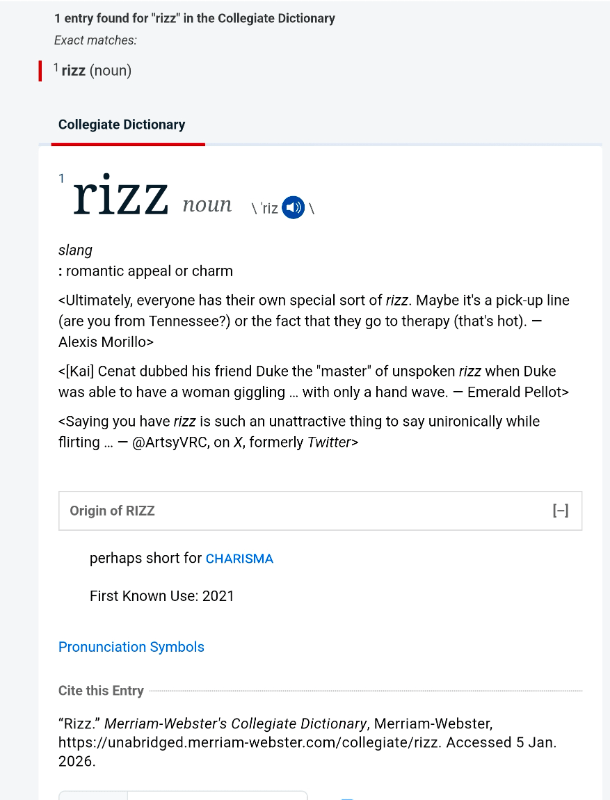

Rizz first emerged in print in 2021; in print dictionaries, to make room to add “rizz,” the lexicographers would have needed to prune elsewhere. With online dictionaries, new words are simply added.

“H. L. Mencken wrote in 1919, [the nation] ‘is producing new words every day, by trope, by agglutination, by the shedding of inflections, by the merging of parts of speech, and by sheer brilliance of imagination” (pp. 7–8). With online publication of dictionaries, these new words can be added without the need for cutting or trimming elsewhere. According to Fatsis, “We are in a golden age for the study and appreciation of words” (p. 8).

When Fatsis concluded his journalistic internship at M-W, he went to Oxford, England, to explore the ultimate English-language dictionary, Oxford English Dictionary (OED), and he attended numerous lexicography meetings, conventions, conferences. He was hooked.

1 Train: To Teach So as to Make Fit, Qualified, or Proficient, 11–23

Noah Webster’s original 1806 A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language contained about 40,000 headwords and cost $1.50 to purchase — when a quart of milk or a dozen eggs cost about $0.02–0.03, and laborers earned less than $1/day. One estimate suggests that $1.50 in 1806 would be about $400 in today’s money. The price of one dictionary could pay for a whole lot of food. (1800–1809 — Prices and Wages by Decade — Library Guides at University of Missouri Libraries, https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/pricesandwages/1800-1809; Comparative wages, prices, and cost of living : from the Sixteenth … – Full View | HathiTrust Digital Library, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89071501472.) Webster’s 1828 An American Dictionary of the English Language contained 70,000 entries and defined the American dictionary for the next two centuries (and beyond?).

The second floor of the M-W building housed about 40 “definers, etymologists, pronunciation editors” and other editorial staffers, as well as about “16 million three-by-five slips of paper known as citations, or ‘cits’—pronounced cites—with examples of word usage culled for more than a century from” a vast array of print and broadcast sources, from newspapers to cereal boxes, restaurant menus to car manuals.

In training to be a lexicographer, Fatsis learned that “the goal of the definer was to put words together in a way that didn’t make them stand out. . . . The best definition is so clear, concise, and comprehensible as to feel obvious” (p. 15). Among the many pages of training guidelines was a quote from Ludwig Wittgenstein, “Everything that can be thought at all can be thought clearly. Everything that can be said can be said clearly” (p. 15). (I’m not so sure about either statement; I manage to have many muddled thoughts, as well as to be completely incapable of stating things clearly at times.)

For Merriam’s chief definer, Steve Perrault, “Words were his life’s work—spotting them, watching them emerge in the language, determining their worthiness for admission to the dictionary, choosing the order of the words used to define them. Perrault was word judge, word jury, and word executioner” (p. 17).

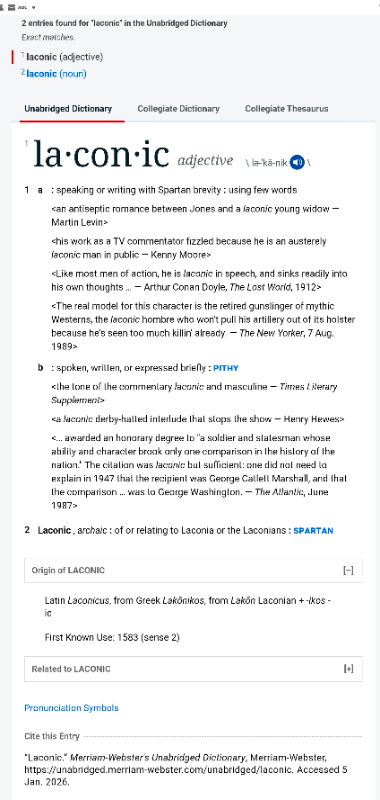

Few people would describe my writing as “laconic,” but Fatsis used the adjective to describe Steve Perrault.

While doing his best to detect undefined words in use, Fatsis noted, “what I quickly came to love—the detective quality of lexicography: searching [large volumes, various sources] for quality cits; composing short definitions and assembling backing data”; and so on (p. 19). He also enjoyed his M-W colleagues, who “were uniformly kind people who seemed to adore their work” (p. 19). M-W staffers don’t have bylines; though their names and credentials were listed in Webster’s Third, and their names were listed in the Collegiate, they’re mentioned nowhere in the online dictionaries.

Dictionaries typically lag in adding words in use, particularly if the word may be seen as off-color. Geoffrey Chaucer used “fart” in The Miller’s Tale in 1386, but the OED didn’t add fart until 1895. Another issue troubled lexicographers before online publications became widely available: “Definers were at the mercy of the cits; they performed deductive guesswork based on tiny scraps of evidence. . . . Digital meandering improved the process of defining words incalculably” (p. 22). Since 2010, M-W lexicographers have used almost exclusively digital sources, though they do still consult the printed cit collections, stored in cabinets.

Best line in this chapter: “‘Many a single word,’ the philologist and OED backer Richard Chenevix Trench wrote in 1851, ‘also is itself a concentrated poem, having stores of poetical thought and imagery laid up in it” (p. 23).

2 History: A Chronological Record of Significant Events (Such as Those Affecting a Nation or Institution) Often Including an Explanation of Their Causes, 24–47

“Noah Webster, Jr., . . . sixth-generation American son of a Connecticut farmer and weaver,” was snobbish. “In his 1828 dictionary, Webster’s second sense of people was: ‘The vulgar; the mass of illiterate persons.’” “Webster wasn’t much for the common man. But when it came to language, he was a champion of the common word. ‘The business of the lexicographer is to collect, arrange, and define, as far as possible, all the words that belong to a language, and leave the author to select from them at his own pleasure and according to his own taste and judgment” (p. 24).

In addition to being a champion of all words in use, he was a champion of the American language, in contrast to British English. He noted that a dictionary of American English was needed because “new circumstances, new modes of life, new laws, new ideas of various kinds give rise to new words” (p. 25). He also advocated for new American spellings, such as plow for plough, jail for gaol, and draft for draught. He dropped the -k from musick and publick and the -u- from honour and colour. He transformed -ise to -ize (e.g., realize), -re to -er (e.g., theater), and -ce to -se (e.g., defense). He added hundreds of new American words, such as revolutionize, presidency, vaccination, including words adopted from Native American sources, such as skunk, tomahawk.

A father of eight, Noah Webster had numerous other pursuits, as well, including his three-volume 120-page reference book set for schoolchildren, which sold millions of copies, stayed in print for >100 years, and paid for his dictionary endeavors. In January 1825, Webster wrote his final entry and then began more than two years of editing his dictionary.

A fellow Yale graduate published it in 1828, the day before Thanksgiving. Webster, 70 years old then, had produced a two-volume nearly 2,000-page dictionary containing “70,000 entries, 12,000 more than the most recent edition of [Johnson’s dictionary]. . . . he also claimed he had written nearly 40,000 definitions of words making their debut in a dictionary of English [including] 4,000 new scientific terms” (p. 29). He added many words borrowed from Native American, Mexican, and European sources. His entries also included quotations not only from the Bible and European sources, but also from Americans, such as Benjamin Franklin and Washington Irving. Though his etymologies were mostly atrocious, based on faulty research, his achievement was groundbreaking. Nearly 200 “years after publication of An American Dictionary, Webster endures as one of America’s most famous names and . . . its oldest brands” (p. 31).

Webster’s 1828 dictionary cost $20 — about $660 in today’s dollars, and its first print run of 2,500 books took 8 years to sell out. Webster, at 82 years old, nonetheless supervised the 1841 publication of its second edition, which included 15 additional pages of new entries he had written. Webster died two years later.

In 1844, the Merriam brothers bought the rights to Noah Webster’s dictionary. “In early 1845, they reprinted the book in a smaller royal octavo edition — eight text pages per sheet of paper, . . . — and slashed the price to $10.50” — nearly half the original price for half the original quarto (4 text sheets/page) size (p. 32).

The Merriams then hired Yale professor Chauncey Goodrich (Webster’s son-in-law) to fully revise the dictionary. Goodrich hired a small staff of scholars to standardize the entries (purging some of Webster’s oddball eccentricities) and to add more than 15,000 new entries. The 1847 edition also shrank both the type size and the white space to further compress the entries into one volume, for which they charged a mere $6 (compared with Noah’s $20 two-volume 1828 edition).

After the 1847 publication, the Merriams stepped up their game even further, hiring Noah Porter to lead a “lexicographic Dream Team” of scholars in etymology, philology, and linguistics, as well as more than 30 subject-matter experts (e.g., geology, astronomy, physics). With the etymologies well in hand, Porter also tackled the pronunciations, “to reflect modern phonetics and the differences in the way Americans spoke” (pp. 33, 34). Porter required a consistent style and format for the entries, too.

The Merriams also astutely marketed their dictionary, such as by sending complimentary copies to dignitaries worldwide, such as Queen Victoria of England. They then obtained quotable praise from these celebrities.

The nation’s Civil War meant mostly cutting off their Southern market, paying higher taxes, and losing some staffers to the war effort. The Merriams nonetheless continued to plow their own money into producing their dictionary. They showed not only bravery but also community mindedness, helping to build Springfield’s first library, holding clothing drives for war refugees, donating dictionaries to numerous groups. At last, the 1864 dictionary “was 1,538 pages long and contained 114,000 entries, 30,000 more than the previous revision and 10,000 more than any dictionary to date, plus [3,000] illustrations . . . 18,492,562” print characters (p. 37; 699 characters in this paragraph, inclusive).

Among the many new entries were ambulance, locomotive, clothes-pin. The definitions, however, were simplified as much as possible — shorter and using “more accessible prose” (p. 37). The Merriams pruned the number of senses of many words, as well (e.g., settle went from 33 senses to 13; dry went from 10 senses to 4). Most important was their use of “a rational, evidence-based, multilayered research and editing process involving dozens of subject experts and trained editors who applied precision and rigor to the definition of words” (p. 38). The Merriams also prudently burnished Noah Webster’s legacy, rather than assailing his original dictionary’s deficits.

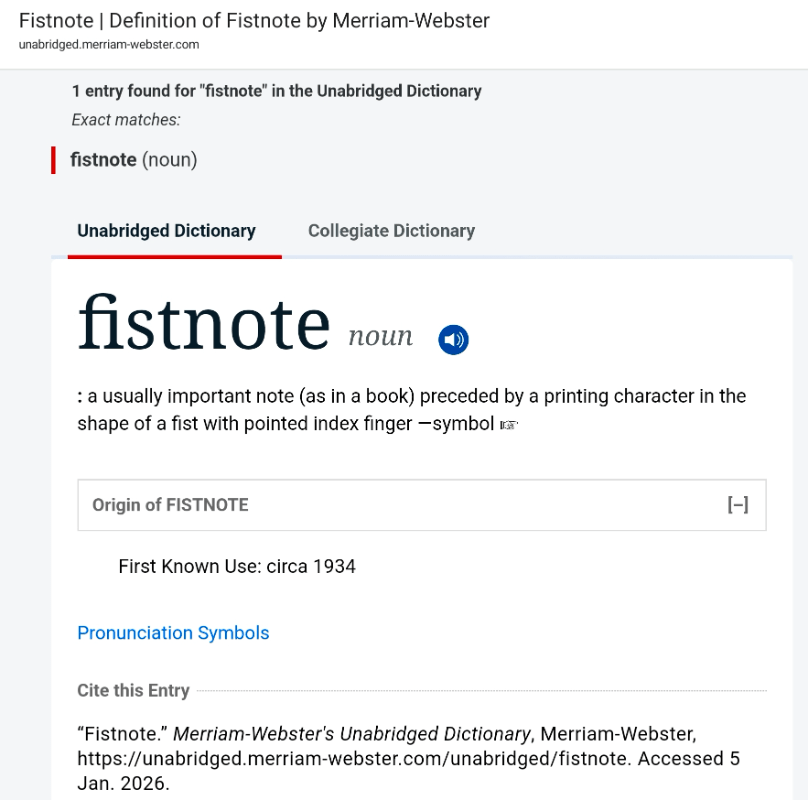

The 1864 edition of the dictionary first used fistnotes to set off usage notes.

Even after the death of both Merriam brothers (1880, 1887), those who have continued their company have astutely continued their business sense, marketing savvy, and high standards for excellence. The Webster’s Second (officially, Webster’s New International Dictionary of the English Language) (1934) contained 600,000 entries, 12,000 illustrations, and 35,000 geographical names, as well as an appendix with 13,000 biographical entries.

The Second wasn’t truly unabridged, however, omitting numerous words deemed vulgar. Nor was it objective, adding usage labels such as “incorrect,” “improper,” “illiterate” to words the editors thought inappropriate. The privileged white males who edited this edition considered themselves true authorities on what words should be used, regardless of which words were actually used. “The creators of the Second believed the dictionary was a rulebook, a set of guidelines to regulate spelling, grammar, and pronunciation—to judge definitively whether a word was improper or incorrect” (p. 41).

“The Third would bring a new philosophy. Its editor in chief, Philip Babcock Gove” had a different outlook (p. 41). Gove “had come to believe that dictionaries should reflect the language, not dictate it—that they should be descriptive, not prescriptive. The Third would still be traditionally thorough— . . . . But it represented a massive departure from its predecessor in substance and style” (p. 42). In place of the Second’s moralistic tone and usage labels, the Third simply indicated standard or nonstandard usage, with only occasional labels for “slang.” This approach ignited a firestorm of protests from prescriptivists, who loathed the Third’s descriptive approach. To this day, there are those who lament the changes between the Second and the Third.

Unfortunately, book binders posed limits on the size of the dictionary; the pages of the Third could not outnumber those of the Second. Gove found new ways to save on space — such as running together each sense of a word, rather than starting each new sense on a different line, pruning commas as much as possible, even preferring phrases to complete sentences or even clauses. Each definition should be so concise that it could be “plugged into a sentence in place of the word it was defining” — that is, “substitutable” (p. 43). Though some words resisted substitutability, most succumbed, changing lexicography thereafter. Gove also stripped out all nonlexical material and deleted 250,000 words considered obsolete, making way for the myriad new words added between 1934 and 1961. The Third contains 465,000 word entries.

When it’s easy to feel overwhelmed with the constant flood of new words as possible candidates for entry into a dictionary, Merriam’s president and publisher, John Morse, suggested that “Lexicography is the art of the possible” (p. 44).

The Third pruned the illustrative quotations, but it also broadened the array of who was quoted, including people not otherwise exalted or celebrated (e.g., crime writers, stage actors). Gove’s Third dictionary seemed to stimulate competition: The Random House Dictionary of the English Language: The Unabridged Edition was published in 1966, though it had been in the works for almost 20 years. In 1969, Houghton Mifflin published The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, which used a professional usage panel of more than 100 “editors, journalists, and professors,” including numerous critics of the Third (p. 46). Despite the turmoil and the competition, the Third sold about 50,000 copies each year for several years. Though the attacks on the Third wounded Gove, he continued to participate in paving the way for a presumed Fourth and writing new definitions. He died in 1972, at age 70.

3 Business: A Usually Commercial or Mercantile Activity Engaged in as a Means of Livelihood, 48–61

At M-W, in 1988, the then-president proposed initiating a Fourth unabridged edition of the dictionary, suggesting that it would take 9 years and $7,000,000 to produce it, adding 300 pages and 50,000 terms to the Third. The company’s profit center, however, was the various editions of the Collegiate dictionary. At that time, the 1983 ninth edition was selling more than 1,000,000 copies/year, had been on the New York Times (NYT) bestseller list for 155 weeks, and was “the top-selling hardcover in American history” (not counting the Bible; p. 49). Three major publishers were already getting ready to publish their own collegiate dictionaries, as well.

Plans for the Fourth were postponed. A print publication of the Fourth now seems highly unlikely. Readers can subscribe to gain online access to the Unabridged Merriam-Webster Dictionary (I paid $49.95/year). More lucrative than the online subscriptions are the advertising income from the M-W collegiate dictionary online, which continues to be available free, with ads. In 1988, the M-W president couldn’t have imagined these circumstances. Even in the mid-1990s, the World Wide Web comprised fewer than 25,000 websites.

In 1995, two tech entrepreneurs grabbed the URL domain names for Dictionary.com, Thesaurus.com, and Reference.com, six weeks before M-W tried to do so. The Dictionary.com websites went live three years later, with public-domain dictionaries, then they obtained licenses for two major print dictionaries — Random House’s unabridged and American Heritage’s.

Almost as soon as M-W published online, traffic “was substantial” (p. 50). The next step was to find ways to make their dictionary rise to the top of Google SERPs — search engine results pages — whenever people look up words. To move up, websites need to do SEO — search engine optimization. Of course, Google doesn’t tell anyone how to optimize their own website to move up in the Google rankings, and as soon as someone thinks they can, Google tweaks the algorithms, and the chase is on again.

Despite their efforts to maintain a large stream of visitors, M-W revenues declined, and its parent company, Encyclopædia Britannica (now based in Chicago) insisted on layoffs; three of the laid-off editors had worked for M-W for a total of 130 years. The three top staffers (including the president and the chief definer) took drastic pay cuts to slow further layoffs. Nonetheless, the layoffs continued, including a lexicographer who had started at M-W in 1968.

“Encyclopædia Britannica was first published in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1768” and served as one of Noah Webster’s resources (along with Johnson’s dictionary) when writing his first dictionary. In 1964, Britannica bought “G. & C. Merriam Company for $14 million,” making the front page of the NYT, which called them “two of the oldest and most distinguished reference works in the English language” (p. 55). Though the encyclopedia brought in greater revenue, the revenue streams were more volatile than the steady income of M-W’s collegiate dictionaries.

Britannica’s purchase of M-W seems prescient. Nowadays, parents who have $1000 to spend on their children’s education will buy a snazzy computer, not a 32-volume, 3-foot-long set of reference books that can’t keep up with the latest information. In 1964, Britannica sold about 175,000 encyclopedias/year; in 1990, a little more than 100,000; by 1995, only 20,000 or so. Not only did Microsoft’s inexpensive Encarta CD-ROM cut into sales, but the rise of other internet resources did so, as well, heralding the print encyclopedia’s demise. In 2001, Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger founded Wikipedia. In 2012, Britannica stopped printing books altogether, and even libraries, colleges, and universities stopped buying as many of Britannica’s pricey online encyclopedia subscriptions.

Britannica had been using M-W revenues to bolster its business income for decades. Britannica’s owner had loved the encyclopedias since childhood. Therefore, when it came time to make budget cuts, he expected the cuts to come from M-W, not from Britannica. To bump up its online readership and therefore its ad revenues, M-W also added other features — puzzles, games, quizzes, blog posts, and so on. Then another blow: Britannica forced M-W president John Morse to retire — with a two-week notice after 35 years with M-W, 20 of them as its publisher.

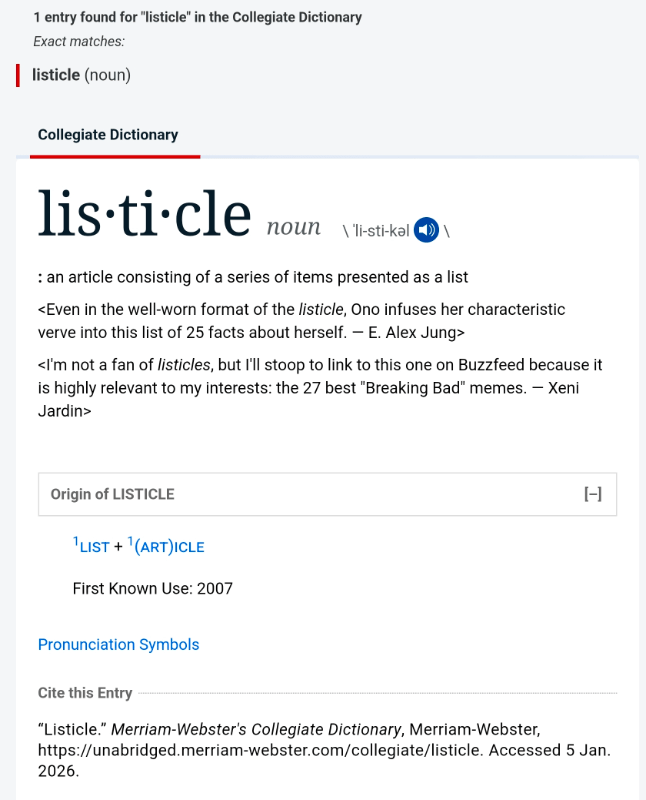

Listicle(a portmanteau of list and article) isn’t found in the subscription M-W unabridged dictionary, but it is defined in the free online collegiate dictionary — as well as in Wikipedia. Once M-W decided not to overhaul the unabridged, the staff focused on updating the collegiate dictionary; presumably, over time, the M-W “unabridged” dictionary may end up being more limited than the “abridged” dictionary.

4 Define: To Discover and Set Forth the Meaning of (Something, Such as a Word, 62–74

Fatsis didn’t name the date when the unabridged was encased “in amber,” never to be updated again, as “everyone seamlessly pivoted to working on the free site” (p. 62). He nonetheless identified several words as among the last words added, thereby indicating an approximation of the last update. The unabridged includes hella, doxxing, and revenge porn, which include 2015 quotations, so I’m inferring that 2015 may have been the last of the “unabridged” updates.

The first documented use of doxxing was 2009, and the most recent quotation cited was in 2015, according to the online M-W Unabridged.

M-W staffers call the free online dictionary OWL — Online Webster’s Lexicon — and a living owl had actually perched outside M-W windows for a time. With the switch from the unabridged to the collegiate, not all unabridged entries would be transferred to the collegiate. Choices must be made. Also, the definitions would need to be made more concise, with fewer quotations and shorter etymologies. Moreover, all of these changes needed to be made using a smaller staff.

When many households and institutions were still commonly buying print dictionaries, M-W had a predictable rhythm: Compile a printed collegiate dictionary every 10 years, gather information for a possible update to the unabridged, and tackle other projects along the way. In this new way of publishing, constant updates were needed. On the other hand, lexicographers had more room for text without being concerned about printed space. They also had easier access to information: more access to quotable text and guides to usage, more research tools, and more feedback on what readers want to find in a dictionary. Of course, that also means raising the bar for providing a superlative dictionary.

Fatsis describes just how challenging it can be to find an eligible new word, to find suitable citations for it, to define it well, and to edit it to fit into the needed dictionary format. He invites the reader along as he pursues various words, searching for the best ones to be added.

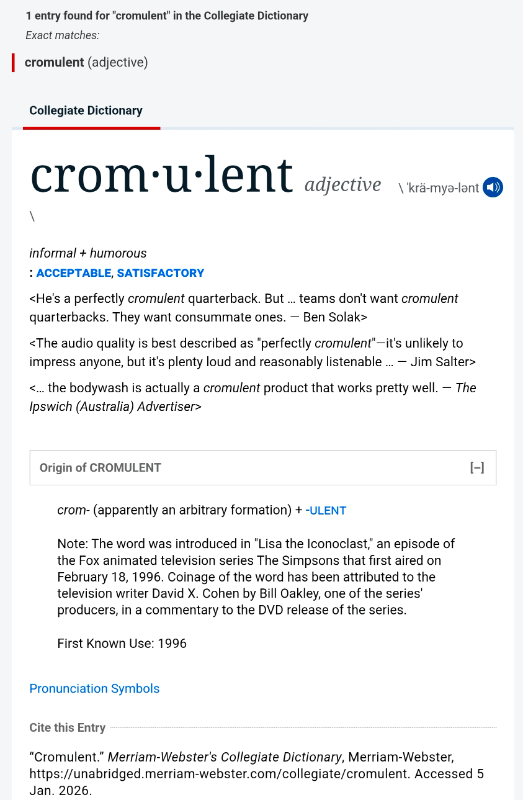

Apparently, cromulent was coined by the writer of the tv series The Simpsons in 1996. It appears in the free OWL (Online Webster’s Lexicon; added in 2023) but not in the subscription unabridged dictionary.

Fatsis posits that M-W is pickier about which words it adds, as compared with the OED (which added cromulent in 2017). That same year, an Oxford press release touted the addition of 46 new words to the OED, only 2 of which were included in the OWL. Five of the words Fatsis had proposed adding to OWL were already in OED. In their defense, however, OWL has had a minuscule staff, as compared with OED, so they needed to be more choosy about which words to ask their staffers to define.

Oxford also took differing approaches for their online dictionary, compared with their print dictionary. Print dictionary words typically needed about a decade of usage before being entered, whereas online dictionary words could be more ephemeral, reflecting contemporary popularity, even if their use didn’t last a decade. An even looser attitude appears at Dictionary.com, where an editor noted, “We’ll add something if enough people are interested in looking it up, and that interest is ongoing” — a crowdsourced method of nominating for entry into the dictionary.

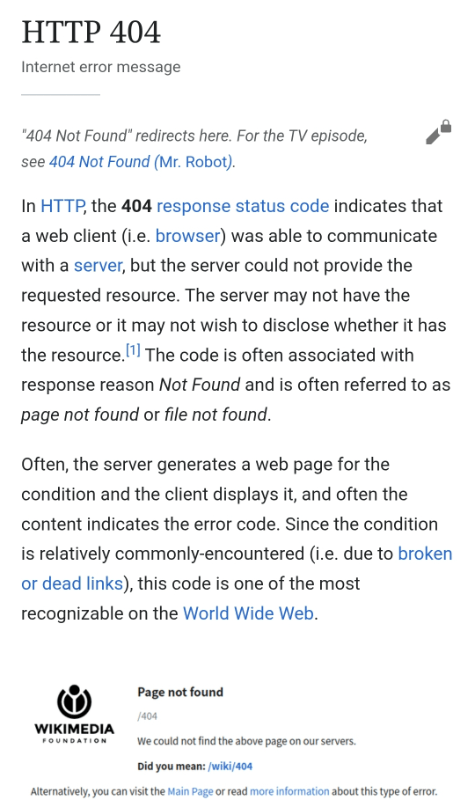

Fatsis mentions the term “404 error,” which doesn’t appear in either of M-W’s online dictionaries, but it does appear in Wikipedia as “http 404, Internet error message.” No websites want to have their visitors see a 404 error while visiting their website.

Both the retired M-W publisher John Morse and the retired chief editor of the OED, John Simpson, noted the problems of adding trendy words while diverting attention from other words, which may be more useful over the long term. Simpson noted, “I did worry that concentrating principally on new words trivialised what we could and should be doing” (p. 73). U.C. Berkeley linguistics professor Geoffrey Nunberg agrees, “If the editors get a moment, they might revisit ‘diversity’ (last revised 1897), ‘demagogue’ (1895), ‘elite’ (1891), ‘insensitive’ (1891)” (p. 73).

Even so, Fatsis would have liked to see all of his suggested additions appear in the OWL.

5 Corpus: A Collection of Recorded Utterances Used as a Basis for the Descriptive Analysis of a Language, 75–90

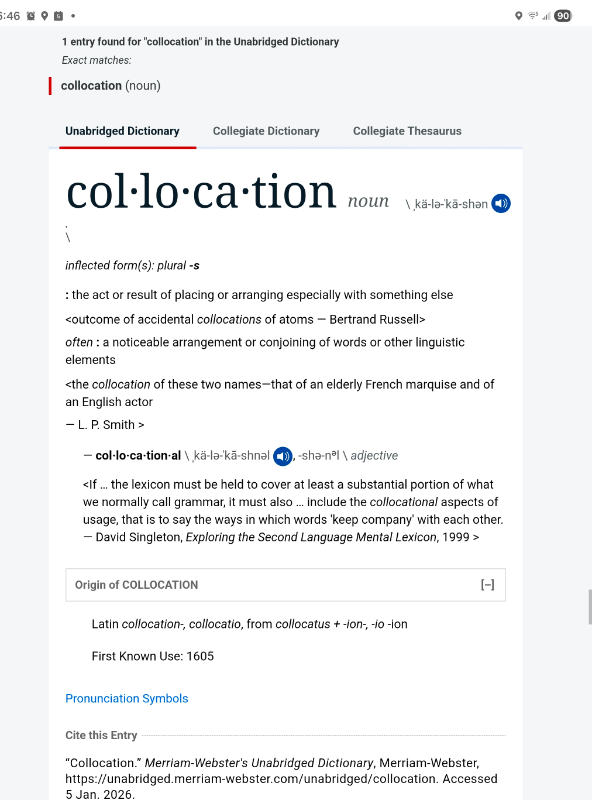

Orin Hargraves is a “computational lexicographer . . . who applies analytical software to giant datasets of language to deliver insights into the meaning and use of words” (pp. 75–76). Among the datasets he used were language corpora — a corpus being “a curated collection of text” (p. 76). One of his analytical tools would yield profiles of various “words, phrases, grammatical patterns, and collocations” (p. 76).

In collocation, words (or other linguistic elements) are located together — co-located.

Long before software tools were routinely used on datasets, linguists were examining large corpora. For instance, two linguistics professors at Brown University assembled a million-word corpus, comprising 500 samples of 2000 words each, across 15 genres of printed material (excluding dialogue and poetry). In the succeeding decades, others replicated their efforts, using other documents. In this century, corpora have included billions of words. These vast corpora allow for searches yielding text related to highly specific topics, as well as to analysis of lexicons, grammar, and other aspects of language.

Many researchers use the Nexis database, which leans heavily on newspapers; in contrast, most corpora purposely embrace a variety of print sources — fiction and advertisements, magazines and books, academic texts and trade journals.

Fatsis contrasted citation-based lexicography, which evaluates words in isolation, based on “human intuition and expertise,” versus corpus-based lexicography, which can “sift through billions of words and identify patterns of linguistic behavior” (pp. 79–80). These analytical tools can yield much more fine-grained information about word usage, with greater accuracy than citation-based lexicography. “Wendalyn Nichols, an editor at . . . Cambridge University Press, told me that corpora allow definers to go ‘from evidence to definition, rather than from what you thought a word meant to finding examples.’ The tools made definers better language sleuths” (p. 80). These analytical tools can also track word usage across time, including how a word is being used — far more detail than tracking the frequency of word searches at the OWL website. Another benefit of corpora-based lexicography is that it can detect low-frequency words that are nonetheless useful to a small proportion of readers.

The OED uses two proprietary corpora: the Oxford English Corpus (OEC), a carefully crafted corpus of 2.5 billion words from “mostly edited sources from around the English world”; and the Oxford Monitor Corpus (OMC), which gathers about 150 million words/month, garnered from recently published internet texts, now adding to more than 10 billion words. The OEC is synchronic, gathered during a fixed time period; the OMC is diachronic, continually changing over time. Using these corpora, Oxford might easily gather 10s of 1000s of “candidate entries”; for each entry, an editor can add not just quotations, but also photos, videos, ephemera, and so on.

With some investor backing, Erin McKean (former head of OED’s U.S. dictionaries), Grant Barrett (lexicographer and language podcaster), and Orión Montoya (computational linguist), joined forces to create Wordnik. Wordnik’s motto: “All the Words” — that is, rather than being arbiters of what words are authentically words, they document words as they are being used. Rather than defining each word, Wordnik links the word to numerous usage examples and lets the searchers infer their own definitions from the examples.

McKean noted, “Words should be celebrated, not judged” (p. 85). Specifically, “Computers would collect words and then mine the web for example sentences that give readers a clear understanding of how a word is used, and how they should use it” (p. 86). In addition, Wordnik has licensed “the latest editions of the American Heritage and Roger’s Thesaurus” (p. 86) and uploaded other dictionaries, Wiktionary, Wordnet (a Princeton database), the text collected in public-domain Project Gutenberg, the nonprofit digital library Internet Archive, and more.

Unfortunately, ad revenues from visitors to Wordnik weren’t sufficient to keep investors motivated, so they turned it over to McKean, who now keeps it going as a labor of love and “an engineering experiment” (p. 87). Through her own efforts, the efforts of various programmers, and the enthusiastic participation of users, she has added more words to Wordnik. Other obstacles presented themselves, too, such as McKean’s need to do other things to sustain herself.

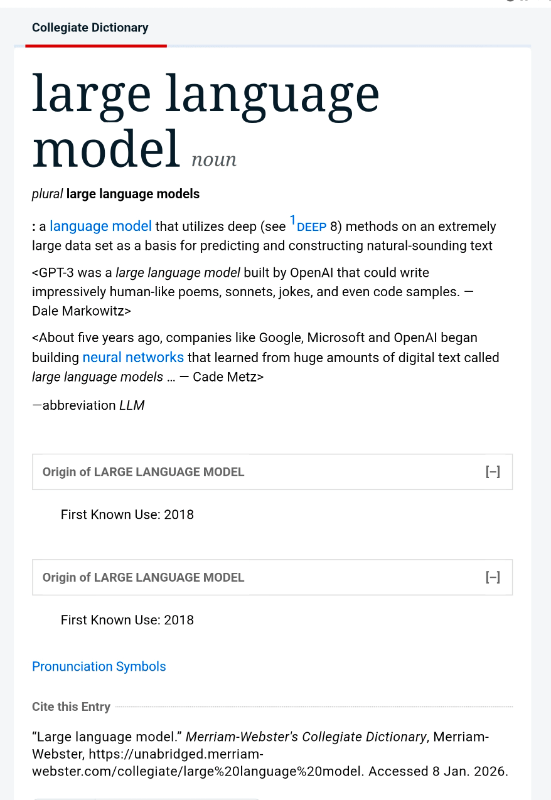

The most challenging obstacle has been the rise of artificial intelligence. Many websites now impose roadblocks to prevent AI-bots from scrounging all their text, thereby impeding Wordnik’s searchers, too. In addition, AI often produces garbage, which can be mistaken for human-authored text, so Wordnik must somehow differentiate human text from AI text — not an easy or speedy task. McKean still hopes she can fulfill Wordnik’s motto . . . sometime.

6 Neologism: A New Word, Usage, or Expression, 91–109

In this chapter, Fatsis discusses how new words — neologisms — are formed. In general, they’re formed by these processes:

- generalization — by which a word with a specific, narrow meaning, broadens in meaning — blog broadened from a person’s Internet diary to mean a person’s (or organization’s) website discussing topics that might not be personal, or a blog may also be an entry on such a website

- specialization — by which a word with a broad meaning might narrow in meaning — Fatsis gives the example that hacker narrowed from meaning any skilled programmer to a talented programmer with devious intentions

- metaphor — by which a word’s meaning can be applied to other contexts — such as virus being applied to computer contexts, not just biological ones

Additional ways to form a new word:

- compounds — e.g., web + log = weblog

- truncation — e.g., weblog shortens to blog

- blending — e.g., video + blog = vlog

- morphological derivation — in which the root word is transformed, e.g., someone who blogs is a blogger

- borrowing — such as borrowing a word from another language — e.g., hector (a bully, a braggart — I wonder why that word came to mind?) is borrowed from the Greek name Hector, a Trojan prince slain by Achilles

Most of the preceding examples are from Fatsis, who got them from English linguist Jack Grieve (“hector” was mine). Grieve had deduced these examples of word formation from his “nearly nine billion words from 980 million tweets written by seven million users across the United States, over one year” (p. 92). Grieve chose this source for his corpus to study “how social media reshapes the native tongue,” as well as how words reshape popular awareness. Two years later, he checked again on the neologisms from his first study and found that “more than half had declined in usage” (p. 93).

Why do some words “stick” while others fade away? “Grieve analyzed staying power based on length; part of speech; ‘word formation process’ (acronym, creative spelling, or standard word formation like compounds, blends, borrowings, etc.); and whether it marked a new meaning altogether” (p. 93). Among these categories, the words offering new meanings had the most staying power and often rose in usage. Also more likely to stick were shorter words — English speakers prefer words of one or two syllables, unlike the speakers of many other languages. Words that were used both in speech and in writing also tended to stick around. Unfortunately, Grieve wasn’t able to get funding to repeat his study a third time, so he doesn’t know whether these trends would have continued.

Hans-Jörg Schmid and his team developed and used NeoCrawler to crawl through the internet (via Google) to find neologisms. Each neologism then had to be identified as either a candidate neologism or garbage. The candidates were then added to NeoCrawler’s database. After crawling through more than 2.6 million web pages, NeoCrawler identified 958 candidate neologisms. It then tracked each one week after week for a decade. Of the neologisms, 80% were nouns, and among the nouns, two thirds were compounds or blends. Between 1950 and 2010, the OED’s added words were similarly predominantly nouns formed through compounding or blending. NeoCrawler’s accuracy of detecting neologisms was verified by noting that “within a few years, you could find all of NeoCrawler’s top [25] most frequent words [e.g., blockchain, dumpster fire] in a Merriam, Oxford, or Dictionary.com database” (p 95). Some of NeoCrawler’s median-frequency words and even low-frequency candidates also made it into these standard lexical databases.

Most neologisms don’t last, and it’s hard to predict which ones will or won’t last. Current databases can document changes, but they can’t yet predict them. In his 1919 The American Language, H. L. Mencken said, that America “shows its character in a constant experimentation, a wide hospitality to novelty, a steady reaching out for new and vivid forms. No other tongue of modern times admits foreign words and phrases more readily; none is more careless of precedents; none shows a greater fecundity and originality of fancy” (p. 97).

Americans also like verb-izing nouns, such as burglar-ize and item-ize. And we adjectiv-ize nouns, too — scar-y, class-y, tast-y. In 1941, the journal American Speech introduced a column “Among the New Words,” originally written by Dwight Bolinger, which continues to this day, documenting the emergence of new words, which now document entries with “links, screenshots, GIFs, memes, and videos” (p. 98). Bolinger himself was quite prescient. “Most of his new words would endure: blacktop, bra, burp, curvaceous, front, fuddy-duddy, G-string, lay an egg, leg up, prototype, quisling, and . . . winterize” (p. 98). His words related to WWII didn’t survive, though.

Bolinger wasn’t trying to predict endurance. He was noting “the first draft of language history” — and those of us who write know that first drafts undergo myriad changes before being finalized (I was on version n of this article when I uploaded it, then I edited it fully twice more, and it will still contain flaws). Language history is never finalized. Bolinger observed, “Often the styles and ideas are transitory . . . so that they leave no mark upon the dictionary” (p. 98).

In 1991, John Algeo (one of Bolinger’s successors, along with John’s wife, Adele) wrote Fifty Years among the New Words: A Dictionary of Neologisms, 1941–1991, which “cataloged every word in the column’s history” up to that point, from AA (an antiaircraft gun) to zippered (from Zipper, a trademark coined in 1926, verbized in 1930, and adjectivized in 1939, according to Webster’s Third online). If you scan Algeo’s index, you can quickly see which words stuck (e.g., 1941’s “newsworthy,” 1979’s “gas guzzler”) and which didn’t (e.g., 1960’s “jumboize,” 1982’s “blenderize”). It’s also fun to see when particular words emerged (e.g., 1950, “shoo-in”; 1988, “couch potato”). A word we should consider reviving: “thobber (1959), ‘a person who prefers guess-work to investigation and reinforces his beliefs by reasserting them frequently’” (pp. 99–100).

Allan Metcalf, professor of English and current (2025) executive secretary of the American Dialect Society (ADS), was lamenting the loss of some captivating neologisms. He proposed that the society start highlighting the “Word of the Year” (WotY), which the society launched in 1990. First “Word of the Year”: bushlips, meaning “insincere political rhetoric,” referring to the first President Bush’s “1988 campaign promise, ‘Read my lips: No new taxes’” (p. 100). Metcalf was gravely disappointed with the choice, hoping instead for neologisms that would endure, not faddish words destined for the scrap heap of language history.

Other members agreed, and the society soon had more rigorous criteria for the WotY, choosing words in wider use and with more potential for staying power. Though many of the WotY’s were still linked to timely events (e.g., 2000, chad; 2008, bailout), the idea still generated media buzz and appreciation of neologisms. In 1996, Webster’s New World Dictionary (no relation to M-W) launched a WotY; in 2003, so did M-W’s OWL; and in 2004, so did OED. By the 2020s, “more than a dozen Words of the Year in English and WOTY season ran from late fall to early January” with the ADS choosing last.

Always in pursuit of generating web traffic, M-W’s OWL lets users choose the WotY (e.g., 2006, truthiness). In 2015, OED chose an emoji, “Face with Tears of Joy,” and OWL chose the suffix -ism. Pretty far from what Metcalf had intended. The following year, the major dictionary publishers chose words based on empirical evidence, based on the words most frequently looked up by users, online. At the annual conference of the ADS, some chosen words were surprising, some were widespread and consequential, others not so much. “Recency bias was common”; if recent events were memorable, the chosen words might stick around, too.

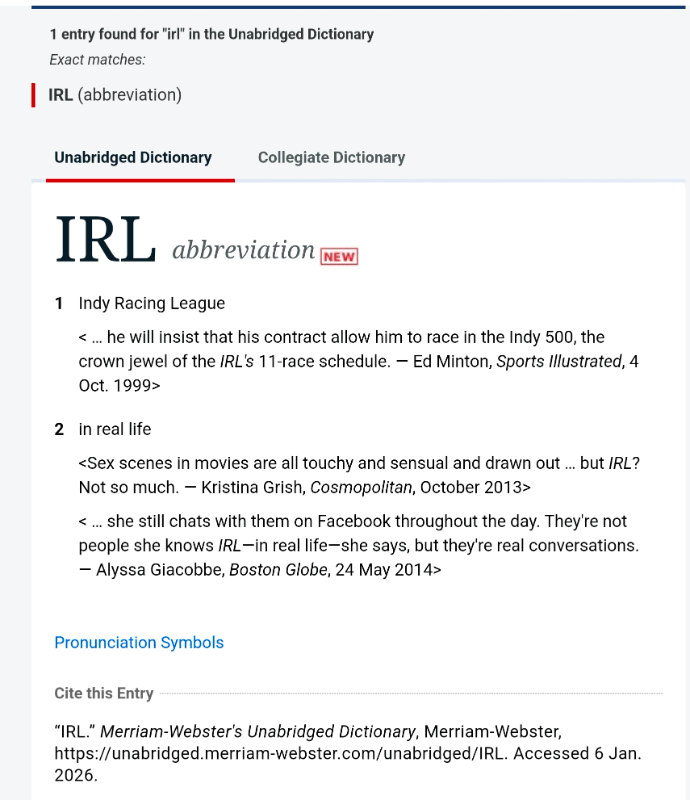

Fatsis noted that the ADS’s annual conference was held online during the COVID crisis but “IRL” before and after the crisis.

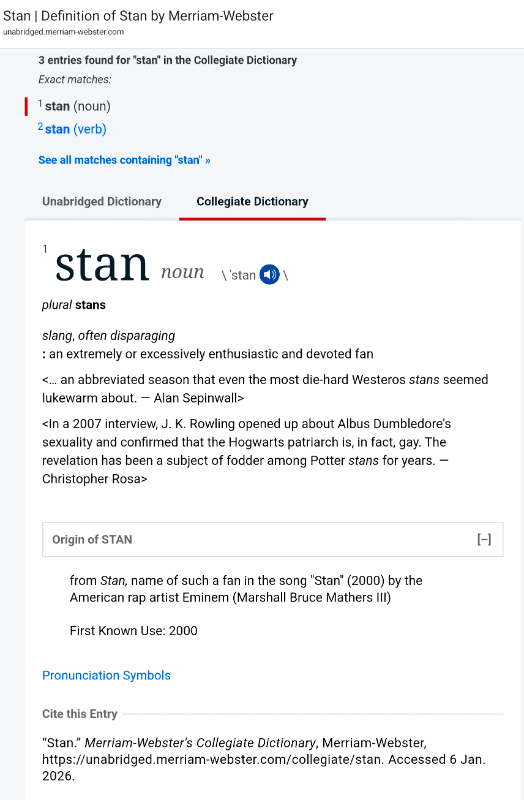

Fatsis casually used the verb stanned, which I had never heard or seen before; Fatsis didn’t even note it as a neologism of the 21st century.

Fatsis then took us behind the scenes in the January 2024 annual ADS conference, including days of diligent analysis and light-hearted speculation in choosing the 2023 WotY. Political concerns and societal considerations were weighed, as well as linguistic ones. After much Sturm und Drang (from a 1776 drama; first use afterward, 1845), the ADS settled on enshittification, which has proven to have staying power. It also met the FUDGE criteria endorsed by Metcalf:

- Frequency of use

- Unobtrusiveness

- Diversity of uses and situations

- Generation of other forms and meanings

- Endurance of the concept.

A word for our times. Well done, ADS. (The 2025 choice was made January 9, 2026. According to https://americandialect.org/woty/ the ADS chose slop, which is also the WotY for M-W’s OWL, https://www.merriam-webster.com/wordplay/word-of-the-year .)

7 Slip: A Small Piece of Paper, 110–134

Fatsis’s favorite thing about his tenure at M-W was “rooting around in the Consolidated Files” of cits, those slips of paper documenting uses of words in context, with dates and authors for each. M-W housed “tens of thousands of pounds of cards and books and sheets of paper crammed inside drawers, stacked in stairwells, smushed into creaky filing cabinets” (pp. 110–111). For Fatsis, these slips were a “portal into the history of American words” (p. 111).

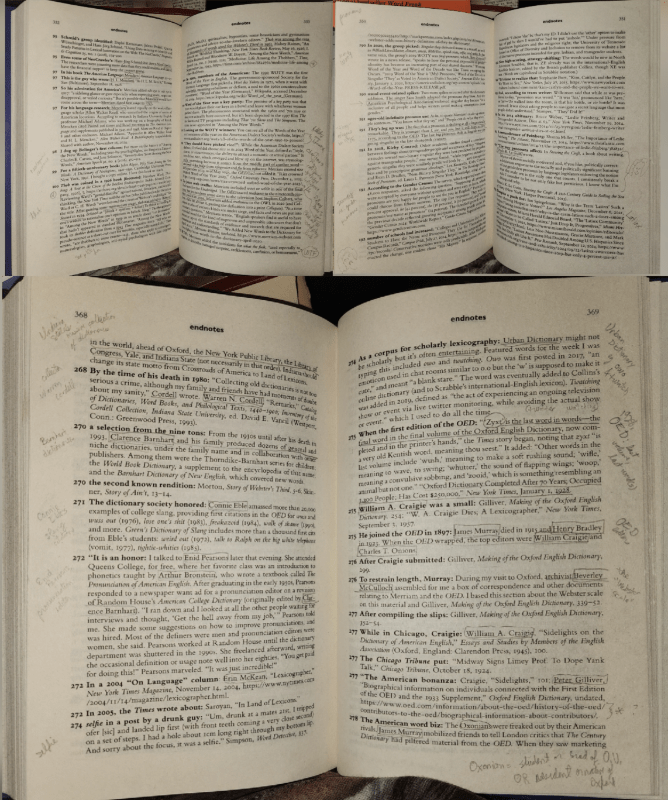

Citation slips have a history even older than Noah Webster. “Samuel Johnson collected about 150,000 quotations for his 40,000 headwords [for his 1755 dictionary] . When James Murray took over in 1879 as editor of the OED,” he inherited more than 200 million 4″×6″ “quotation slips,” now called “citations.” The slips were to be written lengthwise, on one side only, and should include not only the quotation but also the reference source of the quotation.

Of course, not all submissions stuck to these specifications. The OED received “book and newspaper extracts stuck on torn-off bits of envelopes or the backs of theater bulletins,” as well as other odd scraps of paper noting quotations and indicating their sources. The slips were kept in boxes, bags, and even a bassinet, in a corrugated shed purpose-built for the OED editors. Among those who sorted the slips were Murray’s own 11 children. Initially, the slips were sorted into purpose-built bookcases with 1000+ pigeonholes, but the 5,000,000+ slips spilled onto additional bookshelves by 1928, when the first edition of OED was published.

M-W used slips, aka “cits,” as well, but the cits used for making the 1864 dictionary were somehow lost during the move from New Haven, Connecticut, to Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1892. The oldest cits (3″×5″) Fatsis could find in Springfield “date to the first book created there, Webster’s New International Dictionary” in 1909. The cits for this first edition were handwritten on light blue paper and stamped with a 1″ “1.” For Webster’s Second, the cits were stamped with a “2.” By 1934, when the Second was published, the files held 1,665,000 cits.

When Gove took over in 1950, he asked the editors “to read for up to two hours a day and mark words from anything and everything”; as a result, the “editors collected about 80,000 cits a month, or nearly a million a year”; the consolidated files contained about 10,000,000 cits by 1961, when Webster’s Third was published, and almost 12,276,000 by 1976. By the time Fatsis stopped counting, the cits numbered 16,000,000 — not counting cits from existing dictionaries, draft definitions of new words, cross-references, or editor comments and questions.

“The files are a century-long scrapbooking project,” reflecting changing styles; various colors of inks and papers; cursive, manually typed, electronic-typewriter script, and computer printouts; carefully cut or folded clippings from newspapers and magazines; photostatic copies — all carefully dated. They’re “an irreplicable and irreplaceable archive of American English” (p. 113).

Gove was an ardent descriptivist. As such, he worked assiduously to include fuck and fuck up in Webster’s Third. He even defined fuck in his own hand — a rarity; almost all other words were defined by his editors and lexicographers. “Fuck hadn’t appeared in a general English dictionary since 1795,” despite its frequency of use. Fatsis devoted seven full pages (113–120) to describing Gove’s dedicated efforts to have fuck included in Webster’s Third, but alas, M-W’s president, Gordon Gallan, insisted that it be omitted. In 1973, M-W’s eighth collegiate included fuck but not fuck around, fuck off, fuck over, or fuck up. Gove died before fuck and its phrases were added to the Addenda for Webster’s Third, and the OWL includes all but fuck over. The online version of the Unabridged also includes fuck all, but fuck around was still excluded.

The slips also document “conversations” across time, as one editor might make a note to which another will respond months, years, or even decades later. One word that has prompted lengthy conversation across decades is irregardless, touted as authentic by descriptivists (who nonetheless tag it as “nonstandard”) but reviled by those who are irked by its use. The descriptivists have prevailed, and the word remains in all versions of the dictionary since publication of Webster’s Third.

Other dictionaries haven’t kept their citations in readily accessible files. Some are kept in storage . . . somewhere, and some have been discarded altogether. Luckily, the University of Wisconsin has agreed to preserve all the citations used to compile the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), comprising cits gathered from 1963 to 2017, when the National Endowment for the Arts rejected a grant application that would have continued gathering cits (hmmm . . . I wonder who was U.S. President then). Outgoing editor Joan Houston Hall had hoped to have the collection digitized, but the $40,000 price tag wasn’t within DARE’s budget.

The OED also has preserved its cits (“quotation slips”), but the cits from the late 1800s through the early 1900s aren’t easily accessible. They’re stored in a brightly lit basement, requiring multiple entries through doorways in a “warren of halls” (p. 125). In this basement vault are “millions of slips, galleys, fascicles, books, photos, and other evidence of a century and a half of dictionary making” (p. 128). Though out of the way, the basement is well protected by flood alarms, fire doors, and an on-call emergency rescue team. An ongoing, years-long project is to untie every slip, sort and restack them into acid-free folders, and secure the folders with protective ties.

Fatsis’s use of fascicle refers to parts of a book; this meaning of fascicle derives from a metaphorical transfer of the word used to describe small bundles, especially of plants or plant parts.

By the time Fatsis visited the OED basement, “almost half of the entries in the second edition of the OED, published in print [in 1989], had been revised online,” presumably with more to be done (p. 126). When Fatsis visited the OED, it employed about 60 lexicographers and about 60 technical support staffers.

Fatsis notes that J. R. R. Tolkien was once an OED editorial assistant and is thought to have been influenced by that experience when devising his Middle Earth languages.

While at the OED offices, Fatsis was shown the Philological Society of London’s original 1857 proposal for “a complete glossary of the English language,” “an index of words assembled for the OED by [convicted murderer] Dr. William Chester Minor,” and James Murray’s 1885 plea for additional quotations for particular headwords (e.g., barking, barmaid) (p. 128).

The OED also let Fatsis peer through three boxes of slips. Because the first edition of the OED was produced alphabetically, in installments, the slips for assumption–astonish (for the ant–batten volume) were much older than those for snak–snu.

The second edition of the OED was also challenging, as it incorporated the entire first edition, the 1933 supplement, and four additional supplements (1972–1986), along with an additional 5,000 new words or new meanings for existing words. The 20-volume OED-2 contained “291,500 entries illustrated with 2.4 million quotations on 21,730 paper pages filled with [59,000,000] words” (p. 130). The entire set of 20 volumes weighs 137.72 pounds.

When considering what to do with OED’s quotation slips after they’ve been digitally scanned, Fatsis says, “scan everything, upload everything, make it searchable, use it as content—and save the originals. . . . they offer a full, safeguarded record of the important business of lexicography” (p. 131). “The slips are mileposts in the history of language, an index of the minds of the people who created them” (p. 132).

Traditionally, libraries had kept bound catalogs of their books, but in about 1864, libraries started replacing those books with card catalogs — revolutionary at the time. In the 1980s, however, libraries started converting their card catalogs to electronic databases, and tens of millions of book cards were “unceremoniously destroyed.” Some libraries also ceremoniously got rid of their cards, such as by tying them to balloons and releasing them into the skies. (This was before most people realized the devastating ecological consequences of releasing balloons that pollute natural areas and kill naïve wildlife.)

In his endnotes (p. 340, endnote for p. 133), Fatsis mentioned library-card art by Vickie Moore, available at https://www.etsy.com/shop/WingedWorld, from whom I purchased these decoratively painted library cards for Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day; E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web; Doreen Cronin’s Click, Clack, Moo, Cows That Type; and Robert McCloskey’s Blueberries for Sal; as well as several others.

Though electronic library catalogs offer speedy delivery of a known specific author or title, they often neglect some of the added tidbits available from the cards, such as the original price of a book or the date of its acquisition, or simply the appeal of holding something on which a human librarian had added a note. For me, physical card catalogs also offered opportunities for serendipity — stumbling onto a delightful book I hadn’t known that I wanted to read.

Fatsis also noted that there’s a nonzero chance that the entire archive of M-W’s slips would be broken up or destroyed, to make way for newer technologies. To M-W’s John Morse, the archive of cits offer “an incredible repository of information about the language and information about dictionary-making and information about the institution . . . . On the other hand, . . . You can’t keep the entire historical record. I’m not happy about that.”

8 Collection: An Accumulation of Objects Gathered for Study, Comparison, or Exhibition or as a Hobby, 135–156

Fatsis devotes an entire 22-page chapter (of his 397-page book) to the remarkable collection of Madeline Kripke, who particularly specialized in collecting dictionaries and language- and dictionary-related ephemera. Her collection — widely accepted as the largest private collection of its kind and among the biggest collections of any kind — not only filled her large apartment but also storage lockers around New York City. More importantly, Kripke had carefully curated her collection, increasing its value to lexicographers and other lovers of language and of words.

Fatsis wangled a personal invitation from Kripke to visit her collection. “Kripke’s books filled custom-made floor-to-ceiling shelves with glass fronts. They obscured counters, packed cupboards, spilled from banker’s boxes, teetered on the steps of library ladders, towered from almost every plank of hardwood floor. She estimated that the apartment contained 20,000 books. Plus, she said, there were thousands more in cartons in . . . three different storage facilities” (p. 136). She and Fatsis explored the narrow labyrinthine pathways, passing her queen-sized bed, half occupied by a wall of books.

For Kripke, a 10th-birthday gift of M-W’s 6th Collegiate “unlocked the world. With it, [she] could read any book, at any level, and look up whatever she didn’t understand” (p. 137). Each night, she jotted notes of any unfamiliar words she had seen that day. Each morning, she reviewed the words from the previous day, and each week, she went over the week’s new words. Later, she earned a baccalaureate in English then a master’s in Anglo-Saxon at Columbia. After her schooling, she worked as a welfare case officer then got a job editing children’s books. After being laid off, she freelanced as a copy editor and a proofreader, as well as a ghostwriter of romance novels.

Meanwhile, she had started collecting books, including rare dictionaries and other lexical texts. Soon, she was widely known by New York rare-book dealers. Her finds included a 1502 dictionary by an Italian monk ($12,000), an original Noah Webster’s from 1828 ($16,500), and a 1602 Dictionarie in English and Latin for Children. Even a stack of the National Police Gazette from the late 1700s and early 1800s. Though Kripke was cagey about how she became wealthy enough to make these purchases, it turns out that her parents were pals with Susie Buffett and her husband, Warren. Warren helped the Kripkes turn their $67,000 into about $25,000,000. The Kripkes had lived frugally and were generous donors (millions) to worthy organizations, but they still left their Madeline with a big bundle to spend on books. She guessed she had made thousands of individual purchases for her collection, spending more than $1,000,000 on it.

Kripke knew that Fatsis was particularly interested in anything related to the Merriams, and she showed him the personal papers of the younger brother of George and Charles, Homer Merriam; she paid more than $100,000 for them. In that trove of papers, Kripke found the famous March 1844 letter in which “George wrote to Charles about the opportunity to buy the unbound sheets of Webster’s dictionary. (‘Half that book would probably be worth permanently, more than any thing we have, or ever shall have’)” (p. 143). Another treasure: an “April 1849 letter to the Merriam brothers from a Brooklyn newspaperman named Walter Whitman” (p. 144). In it, the abolitionist editor of the Brooklyn Freeman politely reminded the brothers that he had written one long and two shorter notices about the Merriam brothers’ dictionary, and he nudged them to send him a fine leather-bound copy of the dictionary. Leaves of Grass was published in 1855.

When Fatsis met Kripke, she had already spent at least two decades thinking about what should happen to her collection after her death. She flirted with numerous universities and other institutions, but she never made a final decision. In April 2020, COVID killed her at age 76, before she had made arrangements. She hadn’t even left a will. The administrator of her estate, her older brother Saul, was busily trying to compile, edit, and catalog his own accumulated papers, books, and other documents.

A spreadsheet had cataloged about one third of her collection and ran to 1,909 pages. Had Saul wanted to, he could have simply turned over the entirety to a dealer, to sell items or groupings of items separately, forever breaking up the collection, never to be amassed again. Instead, Saul conferred with five lexicographers who knew his sister and asked them how to proceed. They found three universities interested in taking the entire collection at once. Of the three, only Indiana University (IU), a public university system, was willing to commit to keeping the entire collection intact and to pay $780,000 for the collection, along with $70,000 to pack all of it and ship it to Bloomington, Indiana.

In November 2021, about 18 months after Kripke’s death, IU started the process of transporting her collection to Bloomington. Moving vans weren’t allowed on cobblestoned Perry Street, so smaller vans transported the 856 banker boxes from her apartment, across the Hudson River, to a warehouse. There, they were loaded onto large semis and driven 750 miles to IU’s storage facility, arriving in December. There, the semis were unloaded, reloaded into vans and transported to the university to be inventoried. An additional several-hundred boxes were transported from Kripke’s three Manhattan storage facilities to Bloomington.

Fatsis visited the collection’s new home almost a year later (fall, 2022). Of the 60 pallets of boxes, 7 had been unpacked, with their contents displayed on metal shelves, not in any particular order. The remaining 53 pallets held stacks of banker boxes, 3–4 boxes high. Additional boxes were fitted into cubbies along a wall.

“Each box had to be opened, inventoried using bibliographic software called Zotero, repacked and relabeled, and sent to Indiana’s main storage facility” (p. 151). Eventually, each item would need to be entered into a “searchable online database . . . , carefully tagged with identifying metadata” (p. 150). Even more challenging than the books were the myriad documents “comprising hundreds of thousands of pieces of paper [that] would have to be examined and sorted. The project would [probably] take [teams] of part-time catalogers and archivists . . . a decade or more to complete” (p. 151).

At IU, Fatsis was greeted by Erika Dowell, associate director and curator of modern books and manuscripts, and by Michael Adams, dictionary historian and IU professor of English, who would be the chief caregiver of Kripke’s collection. Adams cherished this role, as he had enjoyed a friendship with Kripke since 1997. Adams had already set aside several documents written by renowned lexicographer Eric Partridge and by Robert Burchfield, chief editor of the OED’s second supplement; some M-W advertisements with notes by Kripke; a 1720 dictionary and a 1659 book; and numerous other treasures for Fatsis to see. When Adams had to leave to teach a class, he let Fatsis continue to rummage through the boxes: a 1776 issue of Pennsylvania Magazine edited by Thomas Paine; fascicles and full sets of the OED; and so on. Though Fatsis had never doubted it before, these boxes clearly demonstrated that “Kripke was the undisputed GOAT” (greatest of all time; p. 154).

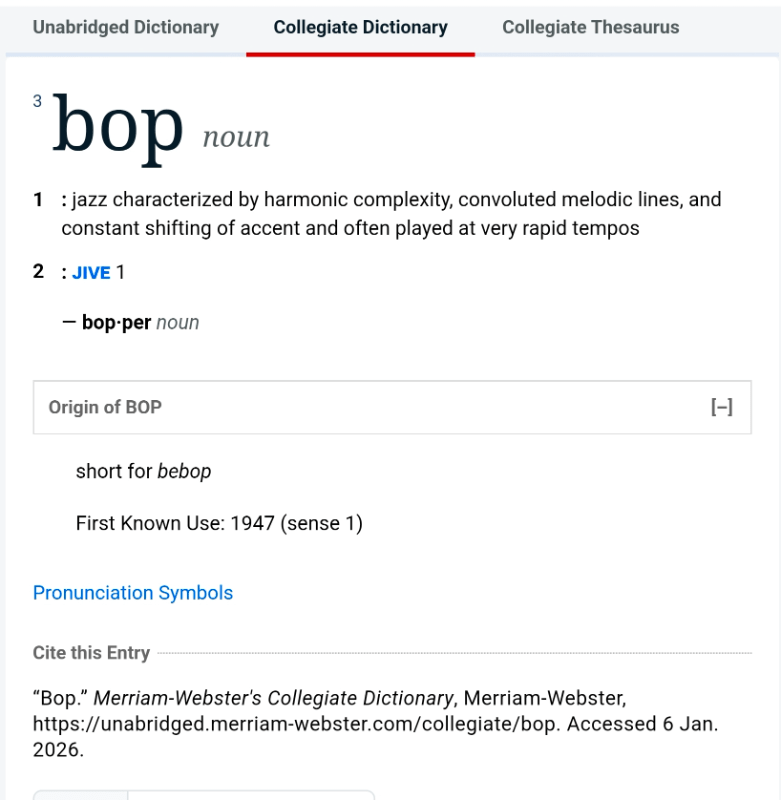

Among the many items Fatsis discovered in the Kripke collection at IU was an autographed copy of Steve Allen’s Bop Tales (1955).

Joel Silver, head of IU’s Lilly Library (which hosts the Kripke Collection) revealed several other items from this library’s collection: George Washington’s acceptance letter to become the first U.S. President; 1 of 26 existing copies of the first printing of the Declaration of Independence; markups on the Bill of Rights, noted by Thomas Jefferson; the earliest known manuscript of Robert Burns’s Auld Lang Syne; the 1941 Best Director Oscar awarded to John Ford for his Grapes of Wrath; a first edition of Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary; and more. The Kripke collection would be in good company.

“Kripke’s ultimate gift was letting others smell and touch and read in the original what she had gathered, meticulously and haphazardly, and figure out for themselves what it contributed to our collective culture” (p. 156).

9 Slur: An Insulting or Disparaging Remark or Innuendo, 157–180

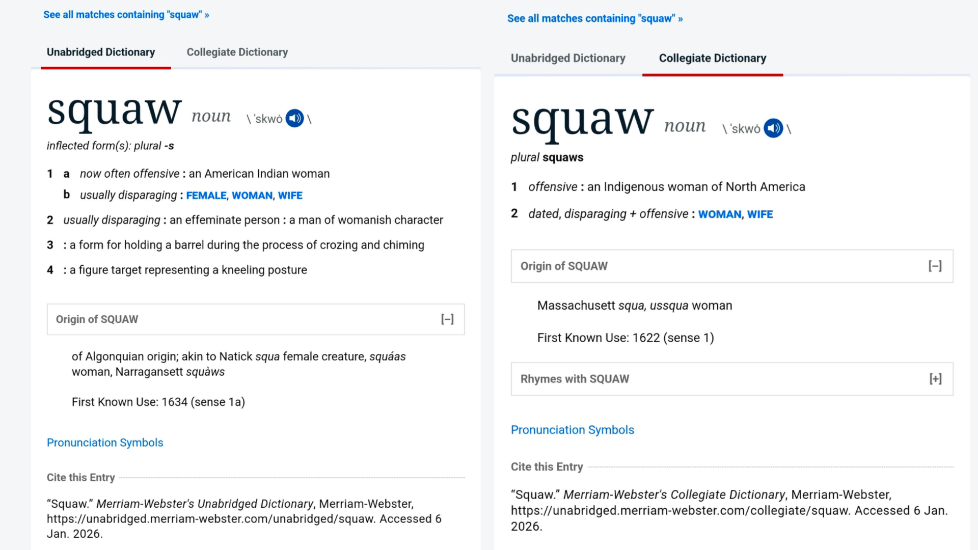

In this chapter, Fatsis addresses how Merriam-Webster handled various ethnic slurs — chiefly, nigger (the n-word), but also squaw and redskin, and he mentions other slurs such as Yid, wop, and greaser. Early dictionary writers used racist quotations by literary luminaries such as Joseph Conrad, with little or no usage notes or other commentary making it clear that such quotations and usages were despicably offensive. Even as recently as 1945, W. Somerset Maugham’s racist quotation was noted simply as “usu. taken to be offensive” (p. 169).

Unlike early editions of the dictionary, the most recent M-W Unabridged identifies squaw as “now often offensive” or “usually disparaging,” and the most recent OWL now clearly calls it out as “offensive.”

Fatsis highlights the views of a few African-American authors who have opined about the use of nigger and whether or how it should appear in the dictionary: author and cultural critic Ta-Nehisi Coates; legal scholar Randall Kennedy, author of Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word; linguistics professor Sonja Lanehart; and linguist John McWhorter.

Particularly insightfully, Fatsis quotes a 1944 slip from the Consolidated files, “Since your work has such a phenomenal educational and informative value, to avoid dissemination of a term which is the bane of colored folk the world over it would be a most humanitarian gesture on your part to exclude the word or term altogether or at least to so treat it in defining it that its usage would constitute a serious ignominy and disgrace to the user” — by “Lieut. Milton C. Wright (a negro)” (p. 162).

10 Pronoun: Any of a Small Set of Words in a Language That Are Used as Substitutes for Nouns or Noun Phrases, 181–200

This chapter addresses the difficult situation in which one wants to use a pronoun to refer to an individual human being, without identifying the person as male or female, she or he, his or her. While they and their allows for indicating multiple humans without signaling gender, there are — to date — no pronouns for indicating an individual human, without signaling the person’s gender.

Up until the 1970s, few writers concerned themselves with this issue, though some had done so in earlier centuries. In 1851, philosopher John Stuart Mill, noted that the lack of a gender-neutral singular pronoun was “more than a defect in language; tending greatly to prolong the almost universal habit, of thinking and speaking of one-half the human species as the whole” (p. 185).

In 1884, Charles Crozat Converse, a lawyer and a composer of church music, proposed thon (a blend of that and one). Thon would refer to just a single individual, either male or female. Converse enthused, “Note its literal and euphonic resemblance to the other pronouns and that its final consonant has a neutral savor significant of its purport” (p. 185). You probably haven’t read thon being used much recently.

Despite the protestations of feminists and others who advocate for the rights of women and for acknowledging them as full human beings, myriad men — usually privileged white men, but not always — asserted that there was no need for a non-gendered pronoun, as the masculine pronoun clearly included females, as well. Even in the 1979 Elements of Style, E. B. White continued William Strunk’s assertion that “the generic he is ‘a simple, practical convention rooted in the beginning of the English language’ . . . and that it ‘has no pejorative connotation’ and ‘is never incorrect’” (p. 183).

In contrast to White’s (and others’) assertion, “Using they/their/them/themselves with a singular antecedent of unspecified gender goes back centuries. The OED dates first use to 1375” (p. 183). Numerous subsequent examples can be tracked throughout the centuries (including in Jane Austen and William Shakespeare). Until the 1700s, when a bunch of grammarians insisted that these pronouns wouldn’t do. To go even further, some grammarians claimed, “‘in all languages, the masculine gender is the most worthy’” (p. 183).

By the 21st century, plural pronouns were more often being used for singular antecedents. In 2015, the Washington Post dropped their ban on using plural pronouns for singular antecedent nouns, and the Associated Press did likewise in 2017. Even Webster’s Third and Merriam’s OWL now acknowledge plural pronouns for singular antecedents. “In short, they is fine” (p. 184).

The earliest known use of epicene dates to the 1400s. Apparently, feminists of the 1970s weren’t the first to notice this lack in the English language.

Converse was not alone in proposing alternative singular epicene pronouns. In the 1920s, the Sacramento Bee did its best to promote the use of hir as an epicene alternative to he or she and used hir in its pages until sometime in the 1940s. Other proposals included “su (1921), ha/hez/hem (1927), she/shis/shim (1934), heesh (1942), che/chis/chim (1951), ve/vis/ver (1970) tey/term/tem (1972), ey/eir/em (1975), ho/hom/hos (1976), sheehy (1978), one (1979), ala/alum/alis (1989) . . . [and my personal favorite,] h’orsh’it” (pp. 187–188). As you may have noticed, none stuck.

A better candidate may be ze, added to OWL’s “New Words” in 2015, defined as “that person—used as a gender-neutral pronoun” (p. 192), but not to the main OWL. Even so, ze dates back to the 1800s, and it has popped up here and there ever since. Online Dictionary.com added ze in 2016, and OED online added it in 2018, noting a first citation in 1864. As of 2025, ze hadn’t gained enough traction to enter the main OWL.

Suffragist Susan B. Anthony had a clever alternative way of responding to the use of he in laws or other legal matter. In that case, “women shouldn’t have to pay taxes or be punished for violating the law. (‘If a wife commits murder let the husband be [hanged] for it’)” (p. 187).

The problem of the singular gender-neutral pronoun becomes even more challenging when we realize it’s possible that gender isn’t always binary — male or female. Specifically, many people now prefer not to identify as just one gender or the other, as just female or male. Now what? In 2015, the American Dialect Society chose they as the Word of the Year “as an identifier for someone who may identify as ‘non-binary’ in gender terms” (p. 189; in 2020, ADS chose they as the Word of the Decade). In 2019, OWL added a new sense for they as “used to refer to a single person whose gender identity is nonbinary” (p. 190). Later that year, M-W chose they as its 2019 Word of the Year.

Among the wider population, acceptance of they is greater for persons born after 1980 than for those born before that year. Even so, a nonacademic survey of respondents age 50 or older revealed that whereas only 40% accepted they as a singular pronoun in 2020, about 70% did in 2024. Quite a jump.

In 2016, OWL added genderqueer pertaining to individuals who don’t categorize themselves as just one sex or the other. The OED dates genderqueer to a 1995 newsletter edited by transgender activist Riki Wilchins. Of course, transgender people have existed throughout human history, but only recently have many felt confident to assert their identity.

11 Entry: Something Entered: Such as : a Headword with its Definition or Identification, 201–215

The new Springfield offices of Merriam-Webster opened in 1940, and photos show a row of metal desks, each one topped by a dictionary stand. By 1955, the offices held a second row of desks, with the added staff needed for producing Webster’s Third, which appeared in print six years later. Both men and women editors were seated at the desks, as “modern Merriam was progressive in its hiring” (p. 201). By the time Fatsis started there, the building and its contents were looking a bit worse for wear.

Fatsis described the editorial floor and his desk, then went on to take us through a typical day there. He spent his first few hours in the dank and dusty basement, reading memos, illustrated definitions, and other material. He helped a colleague with a blog post about liftoff, pulled cits from the Consolidated Files, and relished the sounds of his colleagues at work. “I was happy to be there. I loved the tactile experience of flicking through a cit drawer, the musky smell of the old paper, those handsome gradations of color and fade in the clippings and slips” (p. 204). Best of all was an occasional chance to see one of his own entries on a 3-by-5 slip.

Among the new words he was pondering were smashmouth, dogpile, redshirt, joggle, safe space, microaggression, and alt-right. On looking for existing cits, he found that smashmouth included a cit from his own Wall Street Journal story. Dogpile, redshirt, and joggle were already covered. He found no M-W cits for safe space, and microaggression had only a couple of cits from the 1970s. Fatsis found numerous online cits for safe space, dating back to the 1970s, and he found an apt 1981 cit for it. By the 21st century, its usage was becoming more common, and Fatsis drafted a definition for this entry.

Microaggression was gaining in usage, as well, with citations starting in 1969. In the ProQuest database, which included both academic and mainstream text sources, usage of microaggression was negligible, but it started surfacing among academics in the 2000s, was quoted on NPR in 2010, and doubled in frequency between 2014 and 2015. It was ready for prime time.

Fatsis also documents the emergence of alt-right into usage. Though neo-Nazis were using the term since 2009, mainstream publications didn’t start using it until 2015. Fatsis didn’t find it even in the New Words section of the OWL. So Fatsis found cits and wrote a draft for M-W’s New Words. With substantial editing by Steve Perrault, the chief definer, Fatsis’s entry made it into M-W’s New Words. In the days of print dictionaries, a decade of percolation might be typical for getting a word into the dictionary. By comparison, Fatsis’s entry appeared with lightning speed.

OWL notes the first print use of alt-right was in 2009, when it appeared in a headline on a right-wing website. Other than in neo-Nazi chat rooms and emails, however, it didn’t emerge until 2015.

12 Social Media: Forms of Electronic Communication through Which Users Create Online Communities to Share Information, Ideas, Personal Messages, and Other Content, 216–233

According to Fatsis, the one constant in the history of dictionaries is “the incessant bitching of offended readers” (p. 216). For instance, Webster’s Third Unabridged was reviled for including ain’t (and for excluding fuck). M-W has leather-bound binders filled with letters received from readers. At least 1 in 5 asks why a particular word has been included — or why a particular word has been excluded — or tells M-W that a particular definition is wrong. Most of these letters are polite, and an M-W staffer just as politely responds indicating that the matter has been referred to an editor for investigation.

The majority of these letters fail to recognize the purpose of the M-W dictionaries: to look through popular, journalistic, academic publications and other sources of written or spoken language and to glean from them “evidence of the way words are actually used in written and spoken English” (p. 217). Dictionaries aren’t designed to dictate to readers how they should speak or write, but rather to indicate to readers how others do speak and write the English language. Though most complaints are polite, and the vast majority stop at verbal assaults, occasionally a complainant threatens violence — even forcing the temporary shutdown of M-W offices.

In OWL, the verb set has a total of 36 senses (25 transitive senses; 11 intransitive). In the online Unabridged, I counted 56 senses of the verb set — 40 senses for the transitive verb and 16 for the intransitive, as well as numerous verbal phrases with set); set can also be used as a noun or an adjective. In OWL (and in the online Unabridged), the verb run now has 31 (15 transitive, 16 intransitive). The 31st sense was added by Fatsis; run is also used as an adjective and a noun, as well numerous verbal phrases, from run across to run with. According to Fatsis, the OED includes 82 senses, 230 subsenses, and 130 verb phrases. WOW!

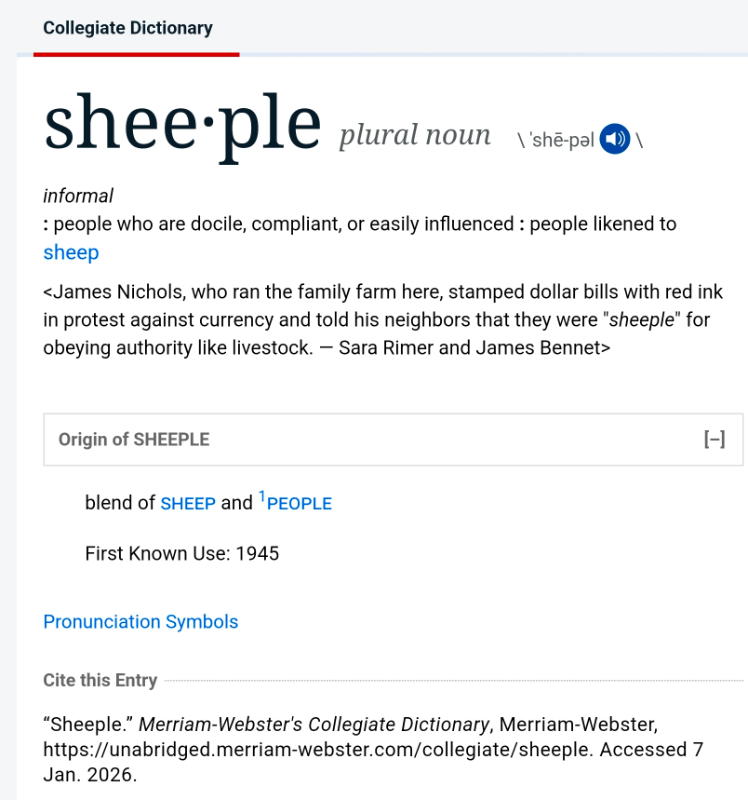

Fatsis’s run entry, his n-word entry, and his other entries generated no noticeable social-media uproar. Except his entry for sheeple, which blew up M-W’s social media almost immediately. At the time his entry was published, it hadn’t been in the Unabridged or in OWL; OED had included it, dating its first use to 1945.

A portmanteau of sheep and people, sheeple didn’t strike Fatsis as particularly unusual or disruptive.

Over another few decades, sheeple occasionally popped up (e.g., 1962, 1974, 1984, 1998), then in 2005, it started rising in usage, reaching 300 citations in 2016. By the time Fatsis drafted his entry, he had an abundance of quotation citations from which to choose. Among them were some right- and left-leaning quotations, as well as this quotation: “Apple’s debuted a battery case for the juice-sucking iPhone — an ungainly lumpy case the sheeple will happily shell out $99 for” (p. 222).

Shockingly — to Fatsis — the Apple quotation prompted extreme outrage; “The Apple army stormed the sheeple entry” (p. 222). Insults were hurled, such as “This is probably one of the most disgusting things I have ever seen” — really? Even “PETA joined the fray, defending sheep as ‘gentle, social, and intelligent animals’” (p. 223). Luckily, PETA urged a boycott of wool, not of M-W. M-W pulled the plug on the Apple quotation. It had, however, generated a lot of buzz about M-W and prompted a burst of activity on the website.

Fatsis moved on from “sheeple-gate” to consider the word troll, now hotly used for social-media contexts, but first known to have appeared in English in 1377, according to the OED. OED added the senses of online troll (verb and noun) in 2006, more than six centuries later. The OED entry dated the online sense of troll to a 1992 Usenet group. OWL added those senses of troll in 2009; even the Unabridged added it in 2014. About that time, Lisa Schneider took over from John Morse and moved M-W toward using social media (Twitter, a blog, etc.) and having a stronger online presence.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, most of M-W’s social media tweets and blogs were uncontroversial, but Lauren Naturale, M-W’s new social-media specialist, couldn’t resist commenting on the misspellings by a braggadocio candidate — unpresidented, honer, leightweight, chocker — as well as the coinages by his advisor, such as alternative facts.

Though many dictionary writers (e.g., Samuel Johnson) had voiced political opinions, M-W had assiduously avoided doing so since the beginning. As soon as M-W was heralded as a leader of the resistance, everything it did was viewed through that lens — even when resistance wasn’t intended. In 2017, M-W was awarded a Webby, which Will Shortz (NYT puzzle editor) presented, saying, “Their Twitter account taught a master class in throwing shade” (p. 231).

Lisa Schneider was less enthusiastic about this kind of attention, however, and 16 months after Naturale started, she was gone. M-W toned down its rhetoric. Even so, M-W profited from the attention, reaching nearly 2 million online followers by 2025, “hundreds of thousands more than Oxford and Dictionary.com combined” (p. 232).

One of the outcomes of sheeple-gate: M-W “added a warning label . . . ‘Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors” (p. 233).

13 News: Material Reported in a Newspaper or News Periodical or on a Newscast, 234–252

The American Dialect Society meets annually to choose not only the Word of the Year, but also other WotYs for specific categories, such as WTF (what the fuck?), for which “bigly” was nominated in 2017. That year’s words (and phrases) tended toward those emerging from the contemporary political situation, such as “tiny hands,” “pussy,” “nasty woman,” “basket of deplorables,” and “post-truth,” as well as “dumpster fire,” which won the category for emoji of the year — and then for WotY!

Also nominated in 2017 for 2016’s WotY was “woke,” which first appeared in novelist William Melvin Kelley’s 1962 essay titled “If You’re Woke You Dig It.” Though “woke” didn’t show up in the rest of the essay, it was included in a sidebar listing “phrases you might hear today in Harlem or in any other Negro community” (p. 237). Other words in the list: busted (arrested), dig (understand), jive (exaggerate), turn on (inform) — which can still be heard 60+ years later. According to Kelley, much of the vocabulary in the wider American society originated in the African-American community — such as cool, chick — and often is passé in that community soon after. According to Kelley at the time, African Americans “can, on the spur of the moment, create the most exciting language that exists in any English-speaking country today” (p. 238).

After Kelley’s death in 2017, others discovered an earlier usage of woke in 1940, when Lead Belly (Huddie William Ledbetter) was telling the Library of Congress about his 1937 song, “Scottsboro Boys”; the blues songster said, “Best stay woke. Keep their eyes open” (p. 239). Others have suggested this usage already existed when Lead Belly said that. Whenever it was first uttered, by 1972, this usage of woke came into wider use, especially reminding African Americans to be wary and watchful, given the myriad threats they faced (and face).