How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave Like Humans”

by John Marzluff and Tony Angell

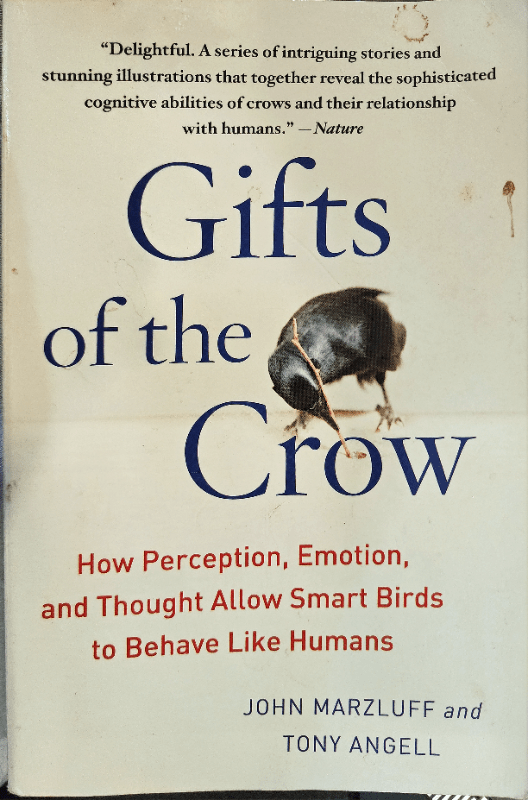

Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave Like Humans, by John Marzluff and Tony Angell

Marzluff and Angell have gathered a charming series of anecdotes about corvids — mostly crows, but also ravens, jays, nutcrackers, and other members of this astonishing family. Angell’s stunning ink drawings beautifully illustrate and illuminate the antics of these birds. The anecdotes are gathered into ten chapters with these themes: “Feats and Connections” with humans, brains and intelligence, language and communication, misbehavior (“Delinquency”), insightfulness, play, emotions and emotional behavior, adventuresomeness and risk taking, consciousness and awareness, and a conclusion that integrates the preceding chapters.

Contents

- Preface xiii–xv

- 1 Amazing Feats and Deep Connections, 1–10

- 2 Birdbrains Nevermore, 11–40

- 3 Language, 41–64

- 4 Delinquency, 65–88

- 5 Insight, 89–115

- 6 Frolic, 117–136

- 7 Passion, Wrath, and Grief, 137–155

- 8 Risk Taking, 156–168

- 9 Awareness, 169–192

- 10 Reconsidering the Crow, 193–206

- [Back Matter, 207–302]

Preface xiii–xv

The authors introduce the corvid family and their tendency toward playfulness and intelligence, as illustrated through anecdotes. They also introduce the notion that we are increasingly able to explore the anatomy and physiology of these birds’ brains, through increasingly sophisticated brain-imaging technology. By the time this book was published, however, “most of the understanding of the inner working of the crow brain was derived from what was known from a few mammals and detailed investigations of song-learning in birds. We hope that you will find, as we have, that understanding some of the neurobiological processes of crows adds mightily to your appreciation of how these remarkable creatures operate so successfully in our dynamic world” (p. xv).

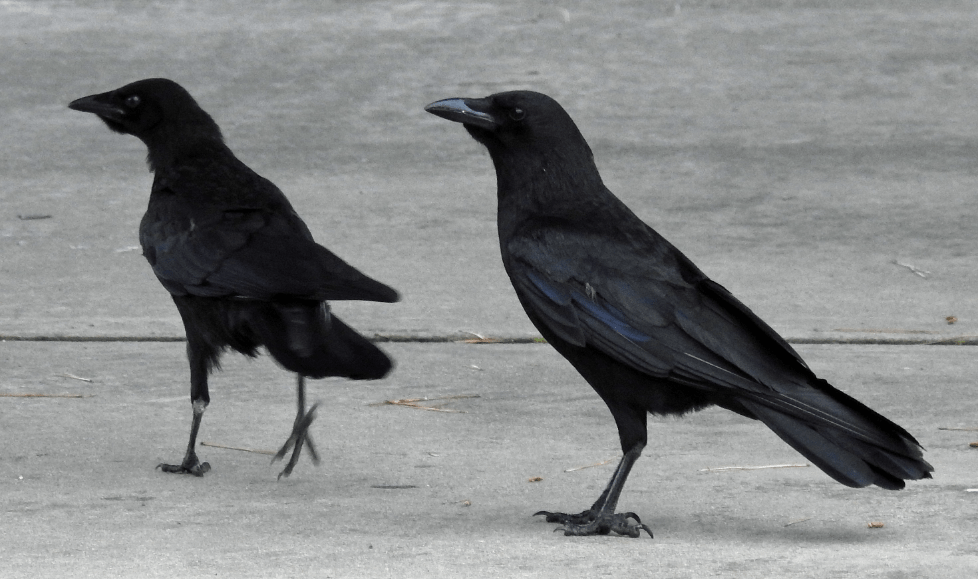

Figure 01a, b. This American Crow and this Common Raven reveal the charisma of the clever, engaging corvid family.

I confess that I wasn’t able to follow all of the authors’ leaps regarding corvid brains, based on the study of mammal brains and the limited study of songbird brains focused on song learning. You may be better able to do so. For me, they seemed more like speculative nonfiction — which was highly entertaining! — than like keen insights into the corvid brain.

1 Amazing Feats and Deep Connections, 1–10

This chapter opens with a New Caledonian Crow named Betty, whose many skills include making tools in pursuit of rewards. Crows and other corvids “are exceptionally smart. Not only do they make tools, but they understand cause and effect. They use their wisdom to infer, discriminate, test, learn, remember, foresee, mourn, warn of impending doom, recognize people, seek revenge, lure or stampede other birds to their death, quaff coffee and beer, turn on lights to stay warm or expose danger, speak, steal, deceive, gift, windsurf, play with cats, and team up to satisfy their appetite for diverse foods . . . . Like humans, they possess complex cognitive abilities” (p. 2).

Corvids have large brains relative to their body size, compared with other birds. In addition, their long life spans and their complex social lives facilitate their development of intelligence and numerous cognitive skills. This book discusses “how crows’ individual and collective social learning abilities enable them to craft tools, communicate subtle messages, plan for the future, intuit solutions, deceive others, and” more (p. 3). On page 4, Angell’s detailed drawing of a crow’s brain suggests brain locations for particular cognitive functions. Though somewhat speculative, it’s based on brain studies of other species, which are applied to the crow.

There’s ample archeological evidence that humans and corvids evolved together, with early hunter-gatherers observing and perhaps interacting with corvids. Traditional folk literature has celebrated corvids around the world. Many indigenous peoples and other cultural traditions have assigned spiritual significance and other importance to corvids in their environments. From caves in France to the Pacific Northwest to Scandinavia, humans have exalted corvids in their language, art, music, religion, and other cultural manifestations. The British Crown has honored ravens resident at the Tower of London since the mid-1600s (with their own Royal Ravenmaster and a corps of British Army Beefeaters). Crows are recognized in our place names (e.g., Crow Landing) and our idioms (e.g., to “eat crow”).

Charles Dickens and his family kept pet ravens, and he wrote of one such pet in an early novel. Edgar Allan Poe read Dickens’s work, and he, too, was captivated by the bird and charmed into writing about it. When Dickens’s favorite raven died, he had the bird stuffed, and it remained in his household until Dickens’s death. It was auctioned after Dickens’s death, and the buyer later donated the bird to the Free Library of Philadelphia, “where, to this day, . . . the old bird remains on display” (p. 10).

Figure 02. It’s thought that one reason that corvids such as these American Crows have developed such large brains and complex cognition is that they’re highly sociable.

2 Birdbrains Nevermore, 11–40

A Clark’s Nutcracker named Hans opens this chapter. Hans is kept in Russ Balda’s research lab, where he’s being studied for his phenomenal spatial memory, a distinctive characteristic of this corvid species. The evolutionary advantage of their spatial memory is that it allows each bird to cache many thousands of seeds (usually pinyon pine kernels) during times of abundance, so that they can retrieve the seeds throughout the lean winter months. Many indigenous people — Anasazi, Hopi, Navajo — have shared this appreciation for nutrient-rich pinyon-pine seeds. Another corvid who prizes these seeds is the pinyon jay, who lives within a complex social structure requiring astute observational skills and social behavior.

Both Russ Balda and Bernd Heinrich have been mentors to author John Marzluff and have inspired other ornithologists to study jays, nutcrackers, ravens, and other corvids. Heinrich’s most-studied corvid is the raven. Heinrich keeps ravens in an aviary, observing their remarkable abilities to solve problems. For instance, the ravens worked together to coordinate the retrieval of food rigged up with a complex network of strings. Ravens also have a “theory of mind,” able to observe the behavior of others (ravens or humans) and to intuit what the others may be observing or thinking or intending. When caching food, if they see that another raven has observed them, they know to re-hide the food, perhaps pretending to cache it where observed, then moving it to a clandestine location. Ravens will follow the gaze of a person, to see what that person is looking at; they can even tell when the person is seeing something that the ravens can’t see (e.g., something behind a barrier). Ravens study human body language, to read its signs.

Another species, the Western Scrub-jay, also caches various food items. It also knows about the perishability of food items and will retrieve more-perishable worms ahead of retrieving less-perishable seeds. They, too, will notice when others are observing them cache food; they’ll return to the cached food and move it to a new spot when not being observed. They even do so when they detect that another bird has heard them cache food in a particular spot. Magpies do so, too.

To study animal brains, neurobiologists use various image-scanning technologies such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalograms (EEGs), as well as physically dissecting brains and slices of brains, to understand the anatomy and physiology of the brain. Thus far, corvid brains haven’t been studied in this manner, but Marzluff and others often infer about corvid brains based on the study of other animal brains. One method of studying corvid brains offered some insight, however: an infrared camera, which detects heat, a sign of high energy consumption. While corvids were flying home to roost, their wings were brightly lit — and so were their heads! It takes a lot of muscle power to fly, and it also takes brain power to do so. (Later in the chapter, the authors noted that human brains consume about 20% of our caloric intake, and corvid brains probably consume a similar percentage.)

In the book’s appendixes, Angell illustrates a neuron, with detailed explanation and description by Marzluff (pp. 211–213); a crow’s central nervous system, with sensory inputs and motor outputs (pp. 214–215); a side view of a crow’s brain and its fundamental structures (pp. 216–217); a top view of a crow’s head, revealing the cerebrum within the skull (pp. 218–219); sensory processing in the crow’s brain (pp. 220–221); motor processing in the crow’s brain (pp. 222–223); auditory processing in the crow’s brain and the avian ear (pp. 224–225); song learning in the crow’s brain (pp. 226–227); emotion processing (e.g., fear, aversion) in the crow’s brain (pp. 228–229); and social-behavior processing in the crow’s brain (pp. 230–231).

The corvid nervous system is also compared with the nervous system of other vertebrates. The embryonic development of corvids is also compared with that of fellow vertebrates.

In addition, the text explicates the bird’s autonomic nervous system (which controls vital life processes), motor nerves (controlling muscles for action), brainstem and cerebellum (for balance and coordinating motor actions), sensory receptors (including receptors detecting Earth’s magnetic field), and the whole sensory system. The authors then integrate how these physiological processes are coordinated in the behavior of crows who beg for food from car passengers awaiting a chance to board a ferry.

These authors also focus on the long-standing gross underestimation of bird brains by scientists, up until very recent times. Even some highly reputable ethologists and other scientists wrongly held that birds behaved based almost entirely on instinct, with little cognitive flexibility or awareness. Scientists have been forced to change this view, based not only on observation of bird behavior, but also on re-assessing the understanding of bird brains and their functionality. Though birds lack the wrinkled neocortex that characterizes human brains, they have different brain structures (in their pallium), which provide similar functionality. One factor affecting these differences is that flying birds must minimize weight wherever possible. Another factor is that most birds rely on sight, whereas the ancient ancestors of humans were primarily nocturnal, reliant on smell and other senses.

Birds rely on memory to adapt to the present environment. Though the hippocampus is the primary brain locus for memory formation, many other brain structures are involved. For example, the amygdala responds to emotions (e.g., fear) to acquire, integrate, and store memories. The forebrain’s executive function directs information to relevant areas of the brain, including to the hippocampus.

At a neural level, some neural pathways are strengthened through experience, whereas others weaken over time. Intense emotions can fortify these pathways, too. While rewards can strengthen neural connections, so can aversive experiences. Neurochemicals influence these connections. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine can enhance short-term memory, can focus attention, and can suppress irrelevant sensory information.

In general, brain size increases with increased body size. More relevant to cognitive capacity, however, is the size of the brain relative to the size of the body. For instance, a blue whale’s brain weighs 13 pounds (6 kg), which is just 0.01% of its body weight. Human brains weigh 3 pounds (1.3 kg), which is about 1.9% of our body weight. Based on brain size alone, blue whales are geniuses, but in terms of relative brain size — not so much. Similarly, raven brains account for about 1.4% of their body weight, and the brain of a New Caledonian Crow comes in at an astonishing 2.7% of their body weight! Surprisingly, some woodpeckers also have relatively large brains, but most of their brain weight is in their cerebellum — for coordination of sensory experiences. For corvids, most of their brain weight is in the cognitive-processing areas of the brain, in the pallium.

As mentioned previously, big corvid brains require a lot of energy, so corvids must eat a high-calorie diet, such as high-fat, high-protein seeds and other foods. Energy consumption isn’t the only limit on the size of corvid brains, though. Flight is. Having a high-calorie diet also means that the corvid digestive system is relatively small and light, facilitating flight.

One of the most useful behaviors of big-brained crows is their ability to reconsider their actions. Their brains allow them to consider their actions before they act, and to reconsider their actions after they act. This facilitates learning from prior experience and applying that learning to new situations. Crows are lifelong learners, and they have long lives, so they can accumulate a great deal of information across their life spans. The authors also point out that part of learning is forgetting irrelevant information — where you cached your seeds last year, how last year’s nestlings behaved, and so on.

Just as sleep is crucial to humans for consolidating memories, it’s crucial for corvids, too. Sleep allows the brain to prune needless information, to fortify important info, and to consolidate memories for long-term storage.

The authors conclude this chapter by reviewing the behavior of Betty, introduced in Chapter 1, and linking her intelligence to the brain processes discussed in Chapter 2.

3 Language, 41–64

The authors introduce this chapter with observations of a crow who repeatedly called “Here, boy!” and whistled to a nearby German shepherd. The dog exuberantly barked in response, provoking its owner to go outside to check what was causing the commotion. Soon after, the crow was seen calling numerous dogs on a college campus, then leading them all on a wild-crow chase through the campus. This crow’s antics continued for awhile, then it disappeared just as abruptly as it had arrived.

Figure 03. To whom is this Common Raven communicating? (Note the raven’s wedge-tipped tail and croaking vocalizations, unlike crows.)

The authors caution readers to be wary of interesting anecdotes, but further investigation revealed the observer to be a reliable witness, and it’s not uncommon for crows to mimic sounds they have heard, especially if the mimicry evokes an interesting response. Around the world, other reliable observers (e.g., Nobel laureate Konrad Lorenz) have noted various corvids engaging in similar astonishing mimicry of sounds — even uttering complete sentences. When magpies have been kept as pets — such as rehabilitated magpies unable to return to the wild — they have often conversed, though with a rather limited vocabulary. Ravens, too, have been noted talkers, including two or three who captivated Caesar Augustus circa 31 b.c.e.

Some corvids will verbally greet their owners (e.g., Konrad Lorenz) but not anyone else and won’t utter any other words. The authors note that for these birds, the corvids use verbal behavior to maintain a social bond, so their utterances chiefly focus on this social relationship. Other rewards may also prompt corvids to vocalize. For instance, a raven at the Tower of London perched on a tourist’s shoulder as he ate his lunch, then whispered, “Keep to the path,” startling the tourist; the raven swiftly grabbed some of the tourist’s food and flew off.

The anecdotes about talking corvids all seem to involve pet birds, or at least presumably pet birds (such as the dog-calling crow introducing this chapter). Though truly wild corvids have not been observed talking, many pet corvids can readily be trained to utter words. When corvids are raised as nestlings, “words, phrases, or noises that are often repeated around a pet [corvid] are quickly included in their vocabulary, accurately learned, and rarely forgotten” (p. 47).

Corvids can’t produce words in the same way humans can’t; they lack the external lips and the tongue manipulation we have. Instead, they masterfully adjust the muscles of their throats to produce utterances we can identify (on p. 49, Tony Angell illustrates the corvid’s physiological vocal apparatus). Many songbirds use the physiology of their throats to produce songs; corvids — which are technically “songbirds” — use this physiology to produce words and other distinctive sounds.

Though the corvid vocal apparatus facilitates vocalizations, more important is the corvid’s brain: “Their large forebrain and a specialized loop between vocal centers in the forebrain and thalamus . . . shape what a crow hears into what a crow says” (p. 50). The authors then explain in detail the auditory physiology of a corvid’s ear (as well as diagrams, pp. 224–227). They go on to point out that just seven kinds of animals have evolved to be able to learn to produce vocal output. Four kinds of mammals — primates (including humans), elephants, bats, cetaceans (baleen whales, dolphins) — and three kinds of birds — parrots, hummingbirds, and corvids. In truth, the vocal learning of songbirds preceded that of humans by about 70 million years; even bats and nonhuman primates could learn vocalizations long before humans could. Other animals may vocalize, but they can’t learn specific utterances by hearing them and then producing them.

Interestingly, just as sleep facilitates other kinds of learning, sleep is also crucial for birds and for humans when acquiring language and learning songs and other specific vocalizations. Scientists have studied songbirds’ acquisition of songs more than the acquisition of other birdy vocalizations. These studies reveal that many songbirds have a critical age for learning songs, after which they have a fixed repertoire. In contrast, corvids continue to “add to their collections of songs and modify them throughout their lives” (p. 53). They’re not one-and-done; they’re continually learning utterances and creating new variations their entire lives.

The authors also discuss the neurological physiology of the brain, governing both song learning and “speech” learning: “Essential to a bird’s ability to learn speech, the HVC [hyperstriatum ventrale pars caudale, in the nidopallium region of the brain] is one of seven interconnected cerebral regions in the songbird’s brain that are analogous to the regions in our [human] brains . . . that control our vocal learning and talking” (p. 54). The same brain region controls parrots’ ability to speak. The authors also explain how types of neurons and neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine) affect the birds’ speaking ability.

For the corvids studied, learning to speak “required extensive revisiting and refining of memories” (p. 57). Of course, many other vocalizations don’t require extensive practice, such as alarm calls, shrieks, and other vocalizations that appear at hatching or soon after. Nonetheless, both humans and crows must have long periods of practice to learn to “speak” or utter other meaningful vocalizations. Furthermore, “talking crows are thinking crows” (p. 57).

Regarding talkative birds, the authors spend a few pages describing Irene Pepperberg’s African Gray Parrot, Alex, and his remarkable ability to comprehend and to communicate using an extensive vocabulary with numerous conceptual complexities (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irene_Pepperberg).

Some corvids have been shown not only to utter individual words and even phrases, but also to answer appropriately to questions, and even to distinguish among some pronouns. Their behavior indicates that they can think and plan what to say when speaking. They seem able to respond to the tonal qualities of human speech, as well as to words. Humans and some birds can use “arbitrary symbols (words) to represent concepts, objects, and relations” (p. 61).

Though all of these observations of corvid speech pertain to domesticated birds, the authors don’t rule out the possibility that we may eventually observe it in wild birds, given increased observations and improved detection techniques. Intriguingly, wild corvid mates have been observed to engage in duets, in which we may someday be able to detect a form of speech communication. Also, wild corvids may imitate particular sounds that carry meaning, such as the sound of a predator to signal danger or the sound of a clucking hen to warn chickens of danger. Even wild corvids readily use vocalizations to gain rewards, deceive others, play, and otherwise communicate with other corvids or with other species. “So much of what we hear from [corvids] is inexplicable. They ring like bells, drip like water, and have precise rhythm. They sing alone or in great symphonies” (p. 64).

4 Delinquency, 65–88

The authors illustrate the delinquent behavior of corvids by describing their destructive behavior and thievery in a national park. Among other things, corvids were ripping up window screens and shredding the rubber of visitors’ windshield-wiper blades and car molding. Thievery included stealing sandwiches, open bags of chips, and grilled foods.

Though it’s illegal to kill these birds, many human “crime victims” have done so, or at least have attempted to do so. Ornithologists suggest a more effective alternative: behavior modification. One effective way to deter misbehavior has been aversive conditioning — associating the undesirable behavior with fearsome or even painful consequences. At a national park, an aversively conditioned corvid pair taught others in the park to avoid the undesirable behavior, as well. Aversive conditioning can be made more effective by pairing it with environmental changes — such as by keeping enticing food out of view and out of reach. Park visitors deterred corvid saboteurs by placing potted plants in front of their window screens and by sliding plastic sleeves over their wiper blades.

It turns out that rubber holds a special fascination for corvids and other birds, even outside of various national parks. They have plucked rubbery radar-absorbent material from military installations; they have completely stripped off the rubber surrounding a windshield.

Other destructive behavior seems linked to territoriality. Even reflective surfaces, such as mirrors and windows, may be subject to attack by defensive corvids or other animals. Desired access to food or water may also prompt unwanted corvid behavior. Unwittingly, humans may provoke or at least reward this misbehavior by feeding the birds at inappropriate locations or at inappropriate times. Hunger may also prompt other misbehavior; many animal parents may have their young attacked by corvids, even killed and eaten by corvids.

Corvids also use tools and human environments to obtain food. For instance, corvids may become familiar with traffic patterns, such as stoplights; they may carefully time when they startle a squirrel or other prey to run into traffic, becoming roadkill for the corvid. Perhaps more alarmingly, corvids have been seen chasing small birds to fly into a closed window, where the bird is stunned or killed and then eaten. Other corvids have been seen luring other animals from their food, or at least distracting those animals so the corvids can swoop in and eat the animal’s food.

Most corvids mate for life; a cooperative pair’s antics can be even more effective. One team effort extracted whipped cream from a can: One bird gripped the head of the can with its feet then pushed the button down with its beak, squirting out cream for the other; then the two switched places. Less innocuously, a pair of corvids will work together to hunt: One corvid flushes out prey while the other corvid dives onto it, then both partake in eating the prey. The authors gave several other examples of teamwork to dispatch and then consume prey, sometimes as large as a seal pup. Gangs of corvids can be even more mischievous — and more deadly. Though not observed to be as calculating and cooperative as chimpanzees or humans, corvid gangs do cooperate to achieve common goals.

Figure 04. Do these two American Crows look like they’re up to some mischief?

Corvids also steal cigarettes, containing nicotine, an intoxicant. More often, corvids (and other birds) consume fermented fruits and other sources of alcohol. They’ve also been seen consuming alcohol from humans, such as by stealing full cans of beer, piercing the cans, and guzzling the contents. Coffee, too, is sometimes sought and consumed by corvids.

The authors also provide numerous examples in which corvids seem to relish mischief for its own sake, even if no other rewards follow. After stealing laundry from a clothesline, cellphones on the grass, or other trinkets from anywhere, corvids seem content to leave their ill-gotten gains in apparently random locations. They seem to relish taking things apart — snowmobiles, windshields, and so on — simply for the joy of doing so. Some corvids also enjoy playing tricks, such as tossing light items at passersby. Or they might steal a food container, eat the food, and then return the empty container to where they found it. Occasionally, a familiar corvid might return a stolen item to its owner — such as dentures or a diamond engagement ring.

Though it’s illegal to kill these birds, there are also government-sanctioned slaughters of corvids; for instance, in 2009, >10,000 crows and 3,800 ravens were killed by the federal government. Better strategies for dealing with troublesome corvids would be to

- Minimize open garbage pits that attract corvids and other wild animals to urban settings

- Modify highways and other roadways to accommodate wildlife and minimize the frequency of roadkill

- Restore wild wolves to our natural environments; when wolves find and eat prey, they leave behind attractive remnants well suited to corvids, thereby attracting them to wild places, rather than urban landscapes

In addition to these policy changes, we can educate ourselves to do more to minimize corvids in our urban environments. Avoid providing food to corvids:

- Don’t feed them

- Tightly cover your compost and garbage receptacles with crow-proof lids

- Use crow-proof bird feeders that allow for consumption by smaller birds but not by large corvids.

- Avoid bird feeders that will scatter food on the ground beneath the feeder.

- Use nesting boxes that will keep crows from getting access to eggs or chicks

- If you have chickens, ducks, or other small animals, provide protective hiding places for the chicks or other youngsters

- If wild birds nest in your area, try to find ways to help the parents protect their young (e.g., fencing off shorebird nests).

- Where appropriate, use aversive conditioning to deter corvids from preying on smaller birds or from destroying property

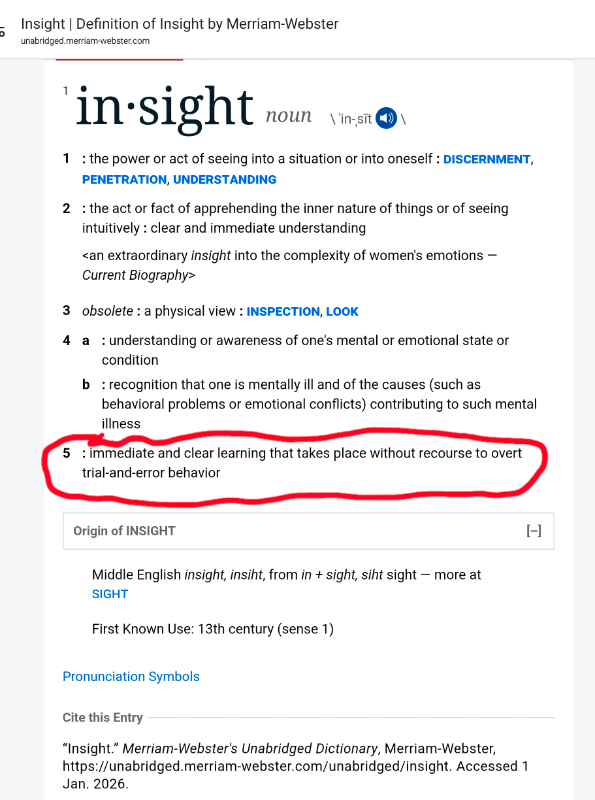

5 Insight, 89–115

In this chapter, the authors suggest that corvids have insight in the sense that they appear to learn without undergoing “overt trial-and-error behavior.” They opened the chapter with an example of a newly fledged raven who “adopted” them as soon as they arrived at a remote lodge in the Pacific Northwest. A nearby raven pair, raising their own three “loudly begging fledglings,” often harassed this scrawny young bird, who felt safe with the small group of biologists. The biologists’ abundant food strengthened this bond. They could see how indigenous peoples easily formed close bonds with corvids. “Our species have mutually shaped each other. . . . we leveraged this fortunate encounter and devised simple experiments to test [the bird’s] mental abilities” (pp. 90–91).

One of their tests was to tie a bit of cheese to string and then dangle the string from the roof. At once, the raven flew to the roof edge, grabbed the string with its beak, and walked backward while pulling the string. The raven then stepped on the string, grabbed it from closer to the cheese, and repeated this process until the bird had pulled the cheese close enough to grab and eat the cheese. No training, no testing, no prior experience, nothing more than insight. The biologists continued to find new food treats to attach to the string, and the young raven deftly retrieved each one.

Other corvids have shown even more remarkable insights, especially New Caledonian Crows, such as Betty, introduced in Chapter 1. Four such crows were given the string test, and all four solved it within 16 seconds. Further experiments revealed that the crows’ speedy responses relied on their being able to see the string (either directly or aided by a mirror) and to watch how their pulling was moving the food closer to them. Perhaps the birds weren’t as insightful as they had presumed. Rather than insight, these corvids were showing curiosity and exploration and eagerness to interact with their environments, modifying their behavior to receive rewards.

Another example of how corvids’ keen observations and analysis led to clever behavior comes from the Seattle Zoo, where Humboldt Penguins are fed fresh trout on a routine schedule. As feeding time approached, wild crows would line up above where the trout were delivered, and any trout that escaped the mouths of the penguins were plucked from above by the crows. The crows thwacked the trout against a rock, stunning or killing it before they swallowed.

Figure 05. I wonder what this American Crow is observing and thinking about as it watches these nesting egrets.

Circa 600 b.c.e., Greek fabulist Aesop told the fable, “The Crow and the Pitcher,” in which a thirsty crow encounters a pitcher of water, but it can’t reach the water with its beak. To get a drink, the crow drops stone after stone until the water level rises enough for the crow to drink. More than 2,500 years later, contemporary ornithologists have tested rooks (a species of corvid) with a similar puzzle. The ornithologists floated scrumptious fatty grubs in a cylinder of water, out of reach of the rooks. These rooks unhesitatingly dropped stones, one by one, into the cylinder, until the grubs were within reach of their beaks. Even when they needed to add lots of stones to reach the grub, they did so without hesitation. Again, however, the scientists can’t conclude that insight was the key to problem solving. The solution may have emerged simply through curiosity, exploration, and observing that their actions were being fruitful.

Some corvids, however, clearly show insight. With New Caledonian Crows, experimenters devised multi-step puzzles, in which each step was neither obvious nor rewarding, until the final step. For instance, a crow might need to pull a string to get a key, to use the key to unlock a box, to obtain a tool, which could be used to get a reward. New Caledonian Crows have successfully used several other multi-step puzzles before obtaining a reward, using a “crazy array of sticks, strings, and boxes” — within 30 seconds (p. 99).

American Crows have also used the human-designed environment to reveal food. Cars line up and wait to get onto the ferry taking them across Puget Sound. As the cars were lining up and waiting, crows were going to the nearby beach, gathering closed clamshells, and dropping them onto the empty roadway leading from the ferry. After about 30 minutes, the ferry pulled up, and about 100 cars drove over the roadway, crushing the clamshells. After all the cars had driven away from the ferry, the dozens of crows landed on the roadway, claiming their clam-meat prizes. The authors note that this behavior may be simple associative learning, rather than insightful behavior.

The food-caching behavior of jays and other corvids may indicate spatial memory, rather than insight. This behavior sometimes also shows that these corvids have a theory of mind, in that they can observe another animal and intuit what it is able to see, think, or even desire. For instance, when corvids notice that another animal is observing them, they may cache decoys, rather than actual food.

In one instance, crows actually hid food from geese. A cook would toss slices of bread toward the geese, but before the geese could reach the slices, the crows would place a large maple leaf atop each slice. When the geese reached for the bread, they’d see the maple leaves, be confused, and leave the bread — which the crows then retrieved.

When the observers are fellow corvids, they “try to fake each other out, seeming to cache in one place but holding their food deep in their mouths and moving to cache it elsewhere” (p. 104). They’re also able to discern whether a particular corvid has or has not seen them hide a cached item; they’re unconcerned about an unknowing corvid but wary of one who knows their hiding place.

Indicative of their theory of mind, corvids pay attention to our eyes and to where we’re looking. They’ll look at where we’re looking, to see what we’re seeing. Very young corvids will stop looking, though, if they see a barrier. By 6 months of age, corvids know that the other individual might be looking past the barrier and will continue to look in that direction. They also pay attention to other body language as an indicator of what the other individual may be observing or thinking.

They can also count up to about six or so. When a group of several observers were behind a “blind,” watching corvids in a pecan orchard, the corvids refrained from stealing pecans. The corvids didn’t resume stealing the pecans until the correct number of observers had left the orchard. The watchers were being watched.

Commonly, wild crows leave small token “gifts” (beads, bottlecaps, candies, pebbles, etc.) for those who feed them or otherwise treat them well. The frequency of these gifts and the persons to whom they are given suggests that these gifts are intentional, not accidental. (The authors also note that dolphins have been observed tossing fishy gifts to birds or to people, p. 111.) Many other birds collect objects — male bowerbirds collect objects for their bowers, parent birds collect objects to adorn their nests — but no other birds have been known to intentionally give objects to humans. The authors suggest that there may be an evolutionary advantage to corvid generosity, in that their gifts motivate humans to offer food and protection to the corvids. It’s not impossible that such gifts are intended to motivate humans toward future beneficial behavior.

In closing the chapter, the authors mentioned a Seattle woman who routinely fed her neighboring crows on a white paper plate. One of these crows occasionally carefully placed the empty plate just outside her back door. Hmmm . . .

6 Frolic, 117–136

“Ravens dive, dip, chase, roll, tumble, somersault, and shout as they ride the wind. The stronger the wind, the better” (p. 117). The authors go on to describe ravens using scraps of bark as wind-surf boards, “hanging eight” of their toes as they slipped and slid on the wind. Though it’s possible there were other motives behind their behavior, observers had no doubt that these corvids were playing.

Ethologists have determined that to qualify as play, the behavior must be (a) unnecessary to survival; (b) voluntary; (c) performed when the bird is safe, healthy, and otherwise not needy; (d) novel (or at least partly novel); and (e) repeated in similar but not always identical ways (I think they include “repeated” to ensure that the behavior wasn’t just a fluke or an accident).

About a third of all bird orders have been observed playing, such as “chickens, ducks, seabirds, cranes, woodpeckers, owls, hornbills, swifts, turacos, parrots, pigeons, songbirds, hawks, and cuckoos . . . . But no group of birds has been reported to play as frequently and as variably, or with as much complexity as the corvids” (p. 119). For instance, groups of corvids have often been seen tossing and catching various small objects.

In Japan, groups of crows will stand at the edge of roofs then “take turns hurling, riding, kiting, and gabbing” as they leap into the air (p. 119).

Wherever snow or ice can be found covering sloped roofs, corvids are likely to take opportunities to slide down the slippery surfaces, then fly back up, repeating this play continually. They may do so in groups or as individuals. They do likewise on natural snow banks, sliding headfirst on their bellies or on their backs, or rolling sideways “like kids in a barrel” (p. 120). Occasionally, they’ll find a lid, to use as a toboggan for sliding.

When slides aren’t available, corvids will find places for bouncing, such as on a flexible tree branch or a slack wire. They’ll grab the branch with their feet or their beak and bob their heads to start the flexing, then they’ll ride the bounce until it stops, only to start the bouncing again.

Though corvids of all ages play, young corvids play the most. Particularly favorite corvid games are tug-of-war, over a scrap of food or other object, or keep-away, in which one bird steals something from another and tries to keep it away from another. Multiple birds may join in playing either game. In tug-of-war, when one bird or group of birds “won,” the roles would switch, and the losers would try to tug the item from the winners. Role reversals occurred often in keep-away, too.

Corvids also play when alone, such as by laying on the back and tossing an item back and forth between feet, between beak and feet, or simply high into the air. They also behave playfully with other species, who may not have as much fun as the corvid. For instance, corvids have been known to tug the tails of turkeys, cats, and dogs. Corvids also taunt cats by pulling shoelaces or other objects across the ground until the cat pounces and scurries after the toy. Some other species also enjoy the play, such as a dog and a crow who chase each other around a tree, back and forth.

Why do corvids play? (1) Play is fun. (2) Corvid lifestyles facilitate play. (3) Play often serves other purposes, as well. The first needs no further explanation. The second may arise because corvids live long lives, often decades, even in the wild. Long lives mean an extended juvenile period, which is when play behavior is most abundant. “A young jay, magpie, crow, or raven will spend months with its parents and siblings on familiar ground, and most will live years before breeding.” With no young to provide for, juvenile corvids have more free time in which to play, and young corvids are also especially social.

Another feature of the corvid lifestyle also facilitates play: They’re generalist omnivores, who happily consume an array of foods — all parts of a plant and any animals available, from any family, at any age or stage. This variety invites a playful approach and an appreciation of novelty.

Figure 06. Most corvids are omnivorous, able to find a variety of food in an array of places, such as this American Crow eating shellfood.

Regarding the functionality of play, “Playing corvids innovate, practice, and perfect skills and manners that are necessary adaptations to flexible, social lifestyles” (p. 128). Through play, corvids learn about their world — predators, prey, potential foods, social behavior with fellow corvids, and so on. “Play builds memories that allow an older bird to live and breed better than a bird that does not play. . . . The benefits of play . . . outweigh the costs [and risks] of play” (p. 128).

The authors go on to explain how play stimulates the release of pleasurable neurotransmitters (natural opioids, as well as dopamine); they also describe how play forms memorable pathways in the brain. (An appendix on pp. 230–231 diagrams the brain’s “social network,” centering around the hypothalamus but also including the amygdala, the septum, the hippocampus, as well as the preoptic area, the pituitary gland, and even the nucleus accumbens.) They then give numerous examples of how the brain physiology might work during play.

They then describe how stress operates in the brain and how stress reduces the likelihood of play. They note also that when corvids play, they form and reinforce memories, which are consolidated during sleep. “Play is a cerebral workout. Players must coordinate emotional and physical responses to their living and material environment. By doing so, they craft critical neural connections among essential parts of the brain involved in memory, emotion, sensory integration, and evaluation of the costs and benefits of actions” (p. 136).

7 Passion, Wrath, and Grief, 137–155

“Crows and ravens routinely gather around the dead of their own species”; the authors illustrate this behavior with numerous examples (p. 138). They rarely touch the body, but it’s thought that they probably recognize the individual who died. There may also be a survival-enhancing benefit to pondering the demise of another, in that if they can see what caused the death, or what circumstances surrounded the death, they may be able to avoid a similar fate.

The authors suggest that the brain’s amygdala may be key to the corvids’ response to death. It’s “at the center of evaluating sensory information of social and emotional significance” (p. 139). The amygdala may then process that information through the visual cortex (which garners greater visual details) and with the hippocampus (which links the experience with other memories). This processing enables the corvid to gain the information needed to avoid dangerous situations and behaviors. The authors also describe the chemicals involved in processing this information (e.g., stress hormones corticosterone and epinephrine; neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine). Other physiological chemicals are depressed (e.g., brain opioids).

Many corvids form lifelong pair bonds, which are central to their social organization. Nonetheless, when one mate dies, the other grieves for a relatively short time before finding a new mate — often a similarly bereaved corvid. This relatively rapid adaptation serves the community of corvids, as well as the individuals. The authors also compare and contrast mammal bereavement behavior (e.g., bison, voles) with that of corvids.

Figure 07. American Crows and many other corvids form lifelong pair bonds and seem to enjoy each other’s company even outside of breeding season.

When a fellow corvid is injured, other corvids have been seen to work hard to revive or to aid their fallen corvid. They’ll aggressively protect their injured fellow from passersby, including big dogs. Nonetheless, if the injured corvid is beyond help, a flock may swiftly switch tactics and engage in a mercy killing, to put the poor bird out of its misery. The authors suggest some of the neurophysiology of both the protective behavior and the murderous assault.

Corvids lack the physiological weapons of raptors (e.g., hooked beaks, crushing talons), but they have the brains to find tools with which to attack or to defend. When corvids fight other corvids, however, they rarely cause injury and typically reconcile quickly, returning to amicable relations. Corvids also often comfort one another, and domesticated birds have been known to offer comfort to their human companions.

Other cultures are known to include crows in their beliefs and in their ceremonies. Crows may take part in ceremonies in Indian ashrams. Various Native Americans — from Alaska to Arizona — esteem crows and other corvids in their traditions, stories, and beliefs, often viewing them as spiritual messengers. The ravens in the Tower of London are carefully tended, purportedly because of the belief that they’re essential to the continuance of the British Empire.

8 Risk Taking, 156–168

The authors open this chapter by noting the remarkable predatory prowess of eagles (or hawks, owls, or other raptors), compared with the relatively weak physiological weaponry of crows. Despite the huge disparity between these two species, groups of crows routinely “mob” (harass) solitary eagles and other enormous predators. Why do that? “Members of species that mob live longer than species that do not” (p. 157). When a group of corvids mobs a predator, they call attention to it, making it obvious to potential prey, and preventing the predator from ambushing or otherwise sneaking up on its prey.

Another risky behavior is scavenging on roadkill. Corvids frequently can be seen feasting on roadkill, despite the obvious risk of becoming roadkill themselves. Often, clever corvids seem to have learned the rhythms of traffic, such as that of stoplights in urban areas. In Japan, carrion crows seem to have memorized the rhythms of stoplights, placing large nuts on the asphalt between traffic signals, so the cars could crush the shells, revealing their contents. These crows also scavenge squashed insects and discarded food. (Recall, too, the crows who took advantage of cars leaving a ferry, to crush clam shells.)

Corvids take risks, but usually calculated risks. For instance, they continue to eat spilled grain on train tracks when a slow-moving freight train approaches, only flying off as it gets too near. In contrast, they swiftly fly off when a fast-moving passenger train comes into view. Crows are also much more wary of cats — which kill nearly 500 million U.S. birds/year — than of dogs, which pose little threat.

Figure 08. This American Crow has a trust-but-verify attitude toward me — don’t fly off immediately, but keep a watchful eye on me, in case I try to pull any funny stuff.

Corvids also seem to have mostly amicable relationships with wolves. Ravens will alert wolves to the presence of carrion, and wolves will allow ravens to approach the carrion after the wolves have mostly had their fill. The authors cite numerous other instances of corvids having playful social relationships with mammals (dogs, humans, etc.). Such relationships are more common when the corvid is a solitary juvenile. For both the corvid and its social partner, the relationship is rewarding for its social nature, as well as opportunities for play, perhaps even other rewards (e.g., food). The authors also indicate possible neurological processes (e.g., release of opioids) involved in this relationship.

9 Awareness, 169–192

Corvids recognize people with whom they interact frequently — or with whom they have an intense experience. The authors give an example of a married couple in which the wife often fed kitchen scraps to neighboring magpies, whereas the husband yelled at them and chased them off. The magpies occasionally left gifts for the wife, but they routinely showered the driver side of the husband’s car window with excrement. When he tried parking in her spot, the magpies nonetheless bombarded the correct car — on the driver side.

Crows not only recognize individual people and their cars, but also individuals of other species, such as dogs. One observer noted that of her two dogs, one ignores crows, but the other nervously barks at them. When she’s walking the barker, crows loudly scold it; when she’s walking the quiet dog, crows leave it alone.

Bird banders often become the targets of corvid abuse in response to humans grabbing, banding, and measuring young corvids. In 2006, Marzluff and some of his students conducted experiments to see whether crows would recognize and remember individuals who had captured and banded them, in contrast to individuals who hadn’t interacted with them. The experimenters wore “cavemen” masks to do the capturing, and they wore Dick Cheney masks when not interacting with the birds. After one negative experience with the “cavemen,” the banded crows scolded the cavemen. Later on, at any time they saw the experimenters wearing the cavemen masks, the banded crows scolded them.

After a while, even unbanded crows also scolded the cavemen, and all crows ignored the Dick Cheneys. So the crows not only identified the threatening individuals who had assaulted them personally, but also identified individuals whom other crows pointed out as threats. The experimenters recorded the crows’ scolding calls and found them to be identical to the calls crows used when responding to hawks, raccoons, and other known predators.

Five years later, the crows still scolded the cavemen mask wearers; even jays, nuthatches, and chickadees joined in the scolding. The offending behavior hadn’t recurred once during the intervening years, yet the birds remembered the offender. What’s more, the vast majority of the scolders had never been touched by the offender. Marzluff believes that these birds will “remember” the offender indefinitely. “Emotionally charged memories are rapidly acquired and longstanding. Fear tends to be especially persistent” (p. 190).

Figure 09. This American Crow parent isn’t the least bit concerned about this fake owl near its youngster. Crows readily differentiate fake owls from living owls.

One way that the knowledge of this threat spread was through parents teaching their fledglings. Another means of transmission is through birds simply observing other birds scold the threatening individual. Corvids — and humans — have brains wired for mirroring the behavior of social peers.

The authors suggest possible neurobiology for the association with the threatening masks and for the scolding response to the perceived threats. Visual processing is linked to emotion processing, to song-learning neural circuitry, and to vocal outputs. Unlike the behavior of some birds, however, the corvids’ scolding call doesn’t vary with the type of predator — eagles, raccoons, and mask-wearing humans elicit the same vocalization.

On the other hand, these corvids also go beyond simple recognition of individuals to consider facial expressions and gaze. They note and respond to the direction of our gaze. They can even recognize a face when it’s inverted or otherwise distorted or disfigured. (They’ll also confirm the identity by turning their own heads upside-down.)

A complex network of neural connections processes the corvids’ recognition of individual humans, dogs, other animals, and even cars. The author (Marzluff) used PET (positron emission tomography) scans to detect the brain processing of corvids while recognizing individuals — either dangerous persons or caring persons. Marzluff details the visual pathways and other brain regions involved — nidopallium and mesopallium, striatum, amygdala, thalamus, and even brainstem (associated with fear responses) were key areas. Like humans, corvids showed greater right-hemisphere activity when presented with fearsome stimuli. When viewing caring individuals, however, their left hemisphere was more active. Amygdala activity also changed in relation to how fearful the stimulus was.

Corvids remember not only threats, but also kindnesses. While a naturalist photographer was photographing ravens and eagles, 100 or more ravens were scolding him and diving at him. He noticed a raven tangled up within a dead deer’s rib cage, so he used his knife to cut away at the ribs until the raven was freed to fly away. The watching ravens were silent as he did so. For the rest of that summer, he was never mobbed by any ravens, and they never stole his food, though they readily stole food from his neighboring co-workers.

Fear can be overcome through repeated acts of kindness (e.g., feeding). Marzluff holds that the repeated kindnesses reduce the animal’s stress level, allowing it to form new memories.

In terms of awareness, few animals — including most primates — are self-aware. One test of self-awareness is to display a mirror to the animal and to note the animal’s response. The vast majority have no idea that the animal in the mirror is themselves. The only bird known to have passed the “mirror test” is the magpie; of five magpies presented with a mirror, three eventually realized that the magpie in the mirror was themselves. The experimenters had drawn a colored spot on the magpies’ throat feathers, visible only in the mirror, and the three self-aware magpies tried to rub away the mark after spotting it in the mirror. Marzluff wonders whether other corvids would show self-awareness if given enough opportunities to view a mirror. (Many great apes show similar self-awareness.)

10 Reconsidering the Crow, 193–206

“Corvids learn, remember, and think in much the same way as do other songbirds and mammals, including humans” (pp. 193–194). We have similar neural physiology. Though our brain structures appear to differ, they share many homologous structures and functions. We also employ similar neural networks, neurotransmitters, and hormones. As long-lived, sociable, innovative, curious animals who adapt to various environments with omnivorous appetites, humans and corvids use our brains to solve problems in similar ways. Brains are costly in terms of development, weight (relative to body size), and energy requirements, so few animals have evolved large, sophisticated brains. For humans and corvids, these costly organs have proven their worth in aiding both of us to inhabit environments across the world and to deftly handle many challenging situations.

Figure 10a, b. Some Common Raven pairs are more in sync than others.

The authors hope that as neuroscientific knowledge of corvids increases, we will develop a deeper understanding of these amazing birds. Already, we have seen corvids show “self-recognition, insight, revenge, tool use, mental time travel, deceit, murder, language, play, calculated risk taking, social learning, and traditions” (p. 198). Humans may differ in terms of the extent of our cognitive processing, but we don’t differ substantially in the kinds of cognitive processing we do.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) prohibits individuals from keeping pet crows, but falconers are permitted to keep and train wild or captive-raised raptors. Some individual states also permit the regulated hunting and killing of crows and many “game birds.” The authors suggest that just as falconers must undergo training to be allowed to possess raptors, interested persons who have received specialized training should be allowed to keep pet crows, with some supervisory stipulations. The authors also offer numerous pros and cons of keeping pet crows. Rehabilitated crows or fostered crows would be a good place to start.

Even if you can’t — or don’t want to — have a pet crow, you can enjoy watching crows in natural settings. “You are likely to find corvids in practically any environment in which humans operate” (p. 203). Shopping centers and food courts are also frequent habitats for crows. Highways, too, attract crows. Your balcony or back yard can be made hospitable to crows simply by ensuring that some food treats are regularly available. No special equipment or training is required (though binoculars may be handy). You can enhance your observations by taking notes (or photos and videos).

“Companions since our birth as a species, crows, ravens, and their kin cause us to briefly step away from our current technological, urban lifestyles and to explore, understand, and appreciate nature. In so doing, they will continue to stir our souls and expand our minds” (p. 206).

[Back Matter]

- Acknowledgments, 207–208

Foremost, the authors thank the many observers who offered anecdotes regarding the behavior of corvids they have seen. They also thank those who helped them produce the book, as well as their own families. - Appendix: Supplemental Images, 209–231

Included are diagrams and explanatory text for neurons; central nervous system and motor nerves; side and top views of the bird brain’s major structures; sensory processing; interaction between sensory and motor processing; hearing and auditory structures; song learning and singing; learning fear and aversion; the social brain network. - Notes, 233–255

Specific references for the preface and each of the chapters vary from just 2 to 24 or more paragraphs. - References, 257–275

About 400 references - Index, 276–287

Well-organized index of subjects, people, individual birds, organizations, and locations - About the Authors, 288–289

Brief biographies of each author

- Readers Club Guide, 291–302

- A Conversation with John Marzluff and Tony Angell, 293–302

- When asked what the authors hoped readers would gain from the book, Tony said, “I would hope that readers . . . would [consider crows] to be exceptional sources of subtle beauty and provocative emotional possibilities.” John said, “If only one thing is gained, I hope it is the knowledge that to call someone a ‘birdbrain’ is a compliment” (p. 302).

- A Conversation with John Marzluff and Tony Angell, 293–302

Text and images by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2026. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment