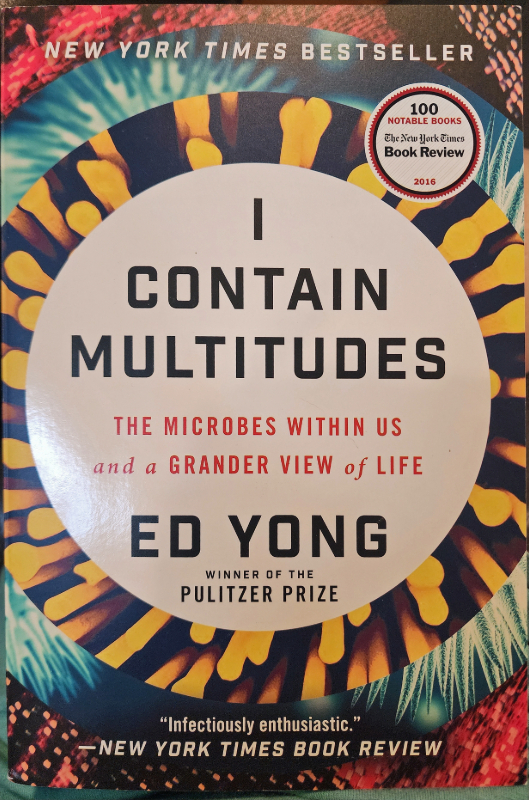

“I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes within Us and a Grander View of Life”

This blog introduces Ed Yong’s I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes within Us and a Grander View of Life, in which he exults in the microbial universe within us and surrounding us.

Contents

- Prologue: A Trip to the Zoo, 1–5

- 1. Living Islands, 7–26

- 2. The People Who Thought to Look, 27–47

- 3. Body Builders, 49–76

- 4. Terms and Conditions Apply, 77–102

- 5. In Sickness and in Health, 103–141

- 6. The Long Waltz, 143–164

- 7. Mutually Assured Success, 165–189

- 8. Allegro in E Major, 191–210

- 9. Microbes à la Carte, 211–249

- 10. Tomorrow the World, 251–264

- [Back matter]

- Acknowledgements, 265–267

- Notes, 269–297

- Bibliography, 299–338

- List of Illustrations, 339–340

- Index, 341–357

Prologue: A Trip to the Zoo, 1–5

Ed Yong had a chance to stroke his hand along the back of Baba, the white-bellied pangolin at the San Diego Zoo, aided by Rob Knight, a microbiologist from New Zealand.

Among the microbes Yong exchanged with Baba are bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses. Like all animals of any size, we humans are living in symbiosis with our microbiota — our microbiome. We are a multitude of microbiotic ecosystems. We have communities of microbes that are particular to our skin, our mouths, our guts, our genitals, and all other body parts that have any connection with the outside world. The skin under our arms have a different community of microbes than the skin on the backs of our hands. None of us live alone; all of us live within a microbial context, and we exchange our microbes with all those with whom we have direct or indirect contact.

Figure 01, a,b. Whether we’re covered with fur (e.g., Sweetie), feathers (e.g., a Sunbittern), scales, skin, or exoskeletons, each of us has innumerable microbes on us and in us, and we exchange microbes with all organisms with whom we share our environment.

1. Living Islands, 7–26

Earth is 4.54 billion years old. Life on Earth started about 3.7 billion years ago, as single-celled organisms — microbes (too tiny for us to see without a microscope). For another 1.7 billion years or more, all living organisms on Earth were prokaryotes, single-celled microbes that lack a cell nucleus and have no cellular mitochondria. There are two types of prokaryotes: bacteria, which are ubiquitous, and archaea, which are rare and mostly found in extreme environments. Another type of microbe is the virus — which can never live independently, but only in collaboration with a living host, so they’re not truly organisms. Viruses probably emerged along with the earliest prokaryotes, but they left no fossil records of their origins.

During the billions of years that bacteria ruled Earth, they governed the break-down and build-up of Earth’s elements — nitrogen, phosphorus, sulphur, carbon, oxygen — to make its soils, its waters, and its atmosphere. Bacteria were the first organisms to photosynthesize, using sunlight as energy to create their own food from air, water, and carbon dioxide. In the process, they released oxygen, permanently changing Earth’s atmosphere to contain more oxygen and less carbon dioxide. Even today, half of the oxygen we breathe comes from photosynthetic bacteria in the ocean.

Figure 02. Billions of years before plants were photosynthesizing air, water, and carbon dioxide, bacteria were doing so. Sunflowers took even longer to evolve on Earth. They probably weren’t domesticated widely until about 2600 B.C.E., in Mexico.

About 2 billion years ago, a bacterium cell entered an archaeon cell, permanently merging with it, such that the bacterium became part of the archaeon. It’s thought that the bacterium was transformed into being the mitochondria of the archaeon cell, thus giving rise to eukaryotes, organisms with cellular mitochondria and nuclei. From this single ancestor, more eukaryotes — animals, plants, fungi, algae — started evolving. Many eukaryotes became multicellular organisms. Only very recently — about 8–4 million years ago, humans emerged, separating from our ape ancestors.

DNA, ATP, and common ancestry: According to Yong, humans and other eukaryotic organisms can readily enjoy a symbiotic relationship with bacteria and other microbes because we share much of our DNA with our common ancestor: bacteria. We, other eukaryotic organisms, and bacteria all use adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to generate and provide energy for driving the basic processes of our cells — nerve impulses, muscle contractions, and even chemical synthesis. ATP is even a precursor to DNA (and RNA), essential to its creation.

Microbes are incomprehensibly numerous, living everywhere from hydrothermal vents deep in the ocean to Antarctic glaciers to the clouds above. According to Yong, your gut alone contains more bacteria than there are stars in the Milky Way galaxy, with each human comprising about 30 trillion human cells and about 39 trillion microbial cells (p. 10). Also, the cells of your body carry 20,000–25,000 genes, but the total of the microbes in your body — your microbiome — carry about 500 times as many genes as those found in your own cells.

Most microbes are not pathogens; fewer than 100 species of bacteria cause infections in humans. Instead, your body’s microbes help you to digest food and extract needed nutrients from your food; to break down dangerous chemicals and toxins; either to crowd out or to actively attack potentially dangerous microbes; to guide our body’s construction and growth; to teach our immune system how to differentiate friend from foe; perhaps even to affect our nervous system and our behavior; and more.

Microbes also aid other animals: Hoopoes (birds) smear bacteria-rich fluid onto their eggs to protect them from harmful microbes; leafcutter ants use antibiotic-producing microbes to disinfect their fungal gardens; zebra-striped cardinalfish host luminous bacteria to lure prey; cattle and other grazing mammals depend on gut microbes to break down the tough plant fibers of the grasses they eat; many invertebrates of the deep ocean (e.g., worms, shellfish) depend on bacteria for all the energy they need; corals need microscopic algae and bacteria to survive. Even plants depend on microbes to extract nitrogen and other nutrients from the soil, nourishing the plants. All life on Earth relies on microbes to decompose dead organic matter, making it possible for new life to emerge.

Figure 03(a–d). Even at the sandy beach, plants — such as kelp (a) — and animals — such as sand dollars (b, flat sea urchins), barnacles (b, crustaceans, related to crabs), Velella velella (c, a cnidarian related to Portuguese man o’ wars), and mussels (d) — carry microbes within them and around them, despite intermittent salt-water baths at high tides.

Fun fact: Charles Darwin, during his life-altering five-year round-the-world voyage on the Beagle, studied not only plants and animals but also microbes. Though the existing technology of his day limited his studies, he also conferred with microbiologists about his findings.

Microbiologists often start out to study microbes by plotting their biogeography — where do they live, and — just as important — where don’t they live? Our own microbiome is shaped by where we have lived, where we have worked, where we have visited, whom we have contacted, what we have eaten, what surfaces we have touched, what air we have breathed, and much more. Though microbes are ubiquitous, many exist only in particular places, and no particular microbe can be found in every location.

Microbes can be very particular in their biogeography. For instance, some microbes that live at the start of the small intestine can’t be found at the rectum, and vice versa. In a person’s mouth, different microbes live beneath the gums versus above them. Many microbes that flourish in the armpit won’t be found on the hand. According to Yong, even the microbe species on your right and left hands differ substantially (just 1 in 6 are found on both!). Each of us has our own genes, but we also have many microbial genes, which also affect our lives, our health, our development, and even our behavior.

Figure 04. Microbiologists such as Rob Knight have taken swabs of penguins and numerous other animals, to investigate what microbes have made their homes on these animals. Microbiologists are also hoping to find out which microbes may be making the difference between healthy animals and animals who are suffering from diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes, colon cancer, etc. (This African Penguin was photographed at the San Diego Zoo.)

Microbes also differ across time. The microbes of an infant differ from those of that person at age three years. Though there’s more microbial stability after that, the microbiome still shows some variation day to day, meal to meal, hour to hour. Changes in health status — such as asthma, obesity, colon cancer, diabetes — are linked to changes in the microbiome. It’s not known whether these correlational changes are also causal — and if so, in which direction does the causality go?

2. The People Who Thought to Look, 27–47

In this chapter, Yong celebrates the many people who have realized the importance of microbes. In 1665, Antony van Leeuwenhoek published Micrographia, compiling his observations discovered by looking at them through the lenses of the microscopes he devised. His microscopes were also used by Robert Hooke and other scientists of his day to see — at last! — the microbial life that had previously been invisible. Over time, van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes reached the scientists of London’s Royal Society. In 1675, van Leeuwenhoek had the idea to study rainwater, becoming the first person ever to see protozoa and bacteria. In 1676, he relayed his discoveries to the Royal Society; in 1677, the society’s Henry Oldenburg published van Leeuwenhoek’s letter; and in 1680, van Leeuwenhoek was invited to become a member of the society, despite his lack of scientific training. In 1683, van Leeuwenhoek examined the plaque on his own teeth, finding still more microbial life, which he called “animalcules.” I highly recommend checking out this Wikipedia article, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Animalcule . In 1723, van Leeuwenhoek, age 90, died, having sparked some scientific interest in his animalcules.

Sadly, though, few scientists appreciated the microbes van Leeuwenhoek and some others were finding; microbes were still grossly underrated. In the 1730s, Carl Linnaeus (father of taxonomy) relegated all microbial organisms to the phylum Vermes (“worms”), the genus Chaos (“formless”). In 1760, Marcus Antonius Plenciz suggested that microbes — which he called animalcula minima (or animalcula insensibilia) — could cause illness by multiplying in the body and by spreading through the air. Unfortunately, he was unable to prove his “germ theory,” so it didn’t gain widespread favor.

About a century later, in the mid-1800s, Louis Pasteur (chemist, pharmacologist, microbiologist) showed that bacteria caused both fermentation (souring of milk) and decay (putrefaction of flesh). In 1865, he showed that microbes were infecting silkworm eggs; by isolating the infected eggs, the remaining silkworms could thrive. A few years later, Robert Koch showed that the Bacillus anthracis bacterium was causing anthrax in cattle, proving that Plenciz’s germ theory was correct. Within another 20 years, the bacterial causes of many other diseases — such as tuberculosis and cholera — were found. In Britain, surgeon Joseph Lister learned of Pasteur’s findings and decided to implement sterile procedures for surgery, publishing a paper describing them in 1867. At this time, microbes were viewed as a disease-causing enemy, with no thought given to their possible beneficial effects.

Figure 05. A key event in microbiology was the discovery of anthrax bacteria in cattle, oxen, and other herbivores, who can be infected while grazing on rough vegetation. (These oxen, living at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park, are well protected from anthrax and other infectious diseases.)

A few decades later, some microbial ecologists, such as Martinus Beijerinck and Sergei Winogradsky, were studying microbes in their natural habitats, where their role as decomposers shined. Microbes were revealed to be useful to plants, making nitrogen from the air available, as well as in making sulphur and other key minerals in the soil available.

Scientists were also discovering lichen as a composite organism made of a fungal host with algae symbionts — symbiotic partners engaged in mutual exchanges. Other discoveries found algae symbionts in other living organisms such as sea anemones and carpenter ants. (The term symbiosis was coined in 1877.) Symbiosis can have three styles:

- Mutualism, in which each symbiotic partner benefits from the relationship, gaining something beneficial from it

- Commensal, in which one symbiont benefits from the relationship, and the other partner neither gains nor loses from the relationship

- Parasitic, in which one symbiont benefits from the relationship, and the other partner loses from it; the loss may be minor, such as losing a few nutrients or some energy, or drastic, such as losing its life, even being consumed by the partner.

Eventually, scientists such as Isaac Kendall realized (early 1900s) that the guts of humans and other animals contained beneficial symbiotic bacteria, which aided in digestion and in extracting nutrients from food. Kendall also pointed to the role of beneficial bacteria in resisting assaults from harmful microbes. Theodor Escherich discovered the Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacterium, pervasive in microbiology research. Despite scientists revealing the importance of beneficial bacteria, the predominant view of microbes highlighted their role as pathogens. By the 1930s or so, the use of antibiotics and antiseptics dominated medical and public health practices.

Fun link: This week’s episode (September 5, 2025) of the Living on Earth radio show interviews a researcher who uses E. coli bacteria to transform plastic into acetaminophen (and ethylene glycol — antifreeze), and he hopes to find many other uses for bacteria to transform plastics and other pollutants into useful products: https://www.loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=25-P13-00036&segmentID=3

Despite these predominant views, Theodor Rosenbury, an oral microbiologist, started studying human microbiota (the microbiome) in 1928, continuing for decades. In 1962, he published his findings in Microorganisms Indigenous to Man, describing “common bacteria in every part of the body in considerable detail . . . . [Among their many benefits,] they might produce vitamins and antibiotics, and prevent infections caused by pathogens” (p. 38).

Rosenbury inspired other researchers, too. René Dubos studied soil microbes and showed microbes to be an essential part of nature, as natural microbial symbionts. (According to Wikipedia, Dubos coined, “Think globally, act locally.”) With colleagues Dwayne Savage and Russell Saedler, Dubos showed the importance of indigenous microbes to the health and well-being of animals, as well as the harm that antibiotics cause to these helpful microbes. A limitation to their research was that so many helpful microbes refused to grow under laboratory conditions. Another technique was needed.

From the late 1960s through the 1970s, Carl Woese started collecting a wide array of bacteria and, instead of trying to culture them, he analyzed whether they contained a particular molecule, 16S RNA. “It forms part of the essential protein-making machinery that is found in all organisms,” allowing for comparisons across all these bacteria. By studying these microbes, he ended up discovering archaea, an entirely different life form from all eukaryotes. Today, not only is his discovery of archaea revolutionary, but so is his use of comparative genetics to study biology.

In the 1980s, Norman Pace started studying the rRNA (ribosomal ribonucleic acid) of archaea in their extremophile habitats (e.g., the scalding hot springs of Yellowstone National Park). He realized that he could simply pull DNA and RNA directly from the environment and genetically sequence them to understand their biology, without having to culture them in a laboratory. These studies would reveal the microbes’ evolutionary biology, and — because he knew their geographical locations — the microbes’ biogeography. In 1984, Pace and his team identified two bacteria species and one archaeon (plural archaea) species solely by their genes alone — the first time that had ever been done. By the time this (Yong’s) book was published, Pace’s team had identified more than 100 species in this way. “Pace . . . and others soon developed ways of sequencing every microbial gene in a dollop of soil or a scoop of water” (p. 43, emphasis in original).

In 1998, Jo Handelsman coined the term metagenomics to describe the genomics of microbial communities. David Relman has relished studying microbial communities in the human mouth and the human gut. He identified nearly 400 bacterial species and 1 archaeon in the guts of just three volunteers; 80% of these species had never been identified before. Scientists were starting to write about the human microbiome — microbiota — as an essential organ.

In 2014, almost 350 years after van Leeuwenhoek published Micrographia in the Netherlands, Micropia opened to the public as the world’s first museum focused solely on microbes. Visitors are immersed in visual displays of microbes, as well as offered opportunities to view living microbes in the real world, through arrays of microscopes. Also on view is the human microbiome, in full size; visitors can see an avatar of their own microbiome, head to toe. Also on view are various lichens, an assortment of stool samples from zoo animals, and the microbes found on everyday surfaces.

Figure 06. At the Micropia Museum in Amsterdam, you can see a macro-sized version of a Tardigrade (“slow walker”) microbe, affectionately called “water bears.”

Exhibit at Micropia Museum Amsterdam, photo taken on 21 August 2015, 14:19:24; Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/o_0/20740531968/ ; Author, Guilhem Vellut; Licensing: This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. You are free: to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work; to remix – to adapt the work under the following conditions: attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

3. Body Builders, 49–76

Yong introduced this chapter with a thumb-sized female Hawaiian bobtail squid, which has two specialized organs for holding bioluminescent bacteria, Vibrio fischeri. The bacteria illuminate the squid’s underbelly, as camouflage. It seems odd to illuminate as camouflage, but without that luminescence, the squid’s shadow would attract the attention of predators. With the luminescence, it blends into the luminous seascape. Squid eggs hatch without these bacteria, but they quickly attract the bacteria to their external mucous lining, then the bacteria move into the squid’s two light organs. The relationship is mutual, with both the squid and the bacteria shaping the squid’s development.

Similar interactions occur within the guts of other animals. Gut bacteria interact with the animal to shape which bacteria will reside where, actually affecting the shape of the animal’s gut. Bacteria had existed on Earth for billions of years before animals arrived, so it’s not surprising that animals quickly formed key relationships with bacteria and that bacteria form an intimate relationship with the animals hosting them.

For many sea creatures (corals, sea urchins, sponges, mussels, oysters, lobsters), during their larval stages, these microscopic larvae drift seemingly aimlessly throughout the open ocean. Only when they find a surface covered with suitable, compatible bacteria, such as biofilm, do they land and undergo a metamorphosis to their sedentary, settled adult forms. Why rely on bacteria to trigger their metamorphosis? Bacteria assure the larvae that “(a) there’s a solid surface, (b) which has been around for awhile, (c) isn’t too toxic, and (d) has enough nutrients to sustain microbes” (p. 61). So, the bacteria signal to the larvae that this location would be a good one for sustaining their lives as adults.

More remarkable than marine larvae is the tiny (1 cm) flatworm, Paracatenula, which is shaped by bacteria throughout its life. The bacterial symbionts of Paracatenula make up about half of its body. In fact, other than its brain, most of the flatworm is made of either bacteria or a place for storing bacteria. If you cut the Paracatenula in half, both halves will become fully functional, even forming a new brain, as needed. You can chop off the tiniest bit of it, and it will regenerate anew, complete with new brain. The only part of the Paracatenula that cannot regenerate is the brain itself because it contains no bacteria. Without bacteria, it has no ability to regenerate.

All of us rely on our lifelong interactions with our microorganisms. Neurologist Oliver Sacks said, “Nothing is more crucial to the survival and independence of organisms — be they elephants or protozoa — than the maintenance of a constant internal environment” (p. 63). Among their vital roles are monitoring and maintaining our immune system, replenishing our gut and skin linings, renewing our skeleton by depositing new bone and reabsorbing damaged bone, replacing old damaged and dying cells with new cells throughout our bodies, storing fat, and even maintaining our vital blood–brain barrier, allowing nutrients to reach our brains but barring many pathogens from doing so.

In our immune systems, microbes guide the development of key organs, make and restore the cells of our organs, create specific kinds of immune cells, and notice potential threats, calibrating our responses to those threats. When our bodies sense a threat, such as an injury or an infection, our primary initial response is inflammation — swelling, redness, heat. These responses help to combat the threat. Unfortunately, some of us respond with inflammation at inappropriate times, such as when we experience asthma, arthritis, and other inflammatory diseases. When functioning appropriately, our microbiome can both excite inflammation to combat threats and suppress inflammation in the absence of actual threats. A well-functioning microbiome reacts without overreacting — sort of an ecosystem manager for our bodies.

Microbes also affect the scents we exude; microbes live in our scent glands, fermenting fats and proteins to produce particular scents — typically as volatile compounds that waft through the air. Different species have different microbial colonies, which produce differing scents. Even within a species, a particular group or even an individual can have a distinctive microbial colony producing a distinctive scent. Among humans, scent glands in our armpits and other locations can produce identifiable scents.

The microbes of a mother can affect the development of her embryo or fetus, including its brain development. Preliminary research suggests that maternal infections or other microbial disorders can affect her child’s brain development. These can lead to behavioral outcomes for the child.

At present, research on probiotics — beneficial microbes, taken to enhance the health of the person’s microbiome — and prebiotics — fiber and other foods that feed beneficial microbes — hasn’t yielded conclusive results. Many of the commercial probiotics use microbes that are easy to grow and to produce but that have limited effectiveness in the human gut. Prebiotics do seem to have positive results in maintaining a healthy microbiome. Maintaining a healthy gut microbiome can be more challenging for elderly people and for alcoholics.

4. Terms and Conditions Apply, 77–102

In 1924, Marshall Hertig and Simeon Burt Wolbach discovered a microbe in a Culex pipens, common brown mosquito, and in 1936, Hertig formally named the microbe Wolbachia pipens, honoring both the scientist and the mosquito. Decades later, once scientists were using Woese’s technique of identifying microbes by sequencing their genes, scientists seemed to find Wolbachia microbes everywhere they looked — at least in arthropods. Except in male arthropods. Their sperm is too tiny to carry Wolbachia. As is so often the case, the Wolbachia microbe offers benefits and drawbacks, it helps and hinders. The host and the context decide what role Wolbachia will play.

In the human stomach, Helicobacter pylori bacteria also play a dual role — causing ulcers and stomach cancers, but also protecting against esophageal cancers (and perhaps acid reflux and maybe asthma). Yong gives numerous other examples of microbes that help in some contexts, hinder in others, or both help and hinder the same host. Typically, symbiotic relationships aren’t easy to define as purely mutualistic or purely parasitic.

The location of a microbe community affects how it interacts with the host. Microbes that thrive in the anaerobic (airless) environment of the gut probably won’t do well on the skin, and vice versa. Even on the skin, our warm moist armpits and groin areas offer contrasting environments, compared with the dry skin on the back of our palms. At the least, the microbes in these locations will perform very different functions and will have quite different interactions with their host.

Figure 08 (a,b). In these highly flattering photos, you can see where I store some of my favorite microbes: my nostrils and the back of my hand. Each location hosts distinctive microbes.

Some body locations aren’t hospitable, such as the acid-filled stomach, where only Helicobacter pylori bacteria and a few other microbes can thrive. In addition, some hosts sequester their microbes in specialized locations, such as the light organs of the bobtail squid for their bioluminescent microbes. About one fifth of insects sequester their microbial symbionts within bacteriocytes, specialized cells designed to house these microbes.

Vertebrates lack bacteriocytes, so our microbes live among our body’s cells; most live outside our cells, such as those living in our gut. The key is to keep microbes in their specialized locations, such as keeping our gut microbes contained within our gut, lined with mucus and epithelial cells. In fact, almost all animals use thick, dense mucus linings to protect sensitive tissues that come in contact with the outside world — our nasal passages, our genitals, our guts (in which the outside world reaches inside), and so on.

Surprisingly, our bodies also use viruses to extend the antimicrobial defenses offered by our mucus linings. Though many viruses harm us — flu, HIV, COVID-19, and more — most viruses actually help us by infecting and killing microbes, including microbial pathogens. These are bacteriophages — phage meaning an organism that eats something. (For instance, coprophages eat feces.) Bacteriophage viruses grab hold of bacteria, inject their DNA into the bacteria, and then turn these bacteria into virus-producing factories that make even more of the bacteriophages. Bacteriophages are particular; each bacteriophage has a favorite bacterium to eat. Luckily, most bacteriophages target our harmful bacteria, not our beneficial ones. Bacteriophages also prefer sticking to our mucus linings, where they’ll find plenty of the bacteria they like to eat, preventing them from escaping the confines of our guts, our noses, and so on.

If microbes do get past the bacteriophages and past the mucus, they reach our epithelial cells. Beyond the epithelial cells are our immune cells, which swallow and destroy any microbes that try to sneak past that barrier. Our immune cells will even proactively reach through our epithelium, slipping between our epithelial cells, to check for the presence of microbes in our mucus lining. They grab these microbes and analyze them, to learn what they need to know about producing antibodies and other defenses against these microbes, as needed.

The immune system can calibrate its response, depending on how many microbes it encounters and whether they seem to be harmful or beneficial. It also creates targeted defenses against known pathogens, such as those causing childhood infections. And it supports and promotes the well-being of beneficial microbes.

Newborns and other infants haven’t had much time to train their immune systems regarding which microbes are beneficial and which are harmful. Nature provided a perfect concoction to help in this process: breast milk, which contains an abundance of mom’s antibodies. According to Yong, “Milk is one of the most astounding ways in which mammals control their microbes” (p. 92).

Figure 08. All mammal moms provide their youngsters with milk that not only provides a nourishing blend of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats, but also a rich source of food for their youngsters’ gut microbes. (Grevy’s zebras, San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park.)

Milk is also a superfood, providing the perfect blend of macronutrients — proteins, carbohydrates, and fats — for the growing infant. For 200 million years of evolution, mammal milk has been perfected to suit mammal infants. The main components of milk are lactose (a carbohydrate), fats, and human milk oligosaccharides (“HMOs” — more than 200 different varieties identified so far). BUT human infants absolutely cannot digest HMOs. Weird, right?

Why on Earth would mammal moms use their energy and their body’s resources to produce a variety of molecules that their infants cannot digest? Let’s follow the milk. The HMOs enter the mouth, go down the esophagus, through the stomach, and past the small intestine, untouched. Then the HMOs enter the infant’s large intestine, which hosts most of the infant’s bacteria. That’s it. The HMOs don’t feed the infant, but they do feed the infant’s gut bacteria. Bifidobacteria longus infantis (B. infantis), beneficial microbes, dominate the stool of breast-fed infants but not the stool of bottle-fed infants. B. infantis bacteria are nourished by mom’s milk and, in turn, these bacteria nourish the infant, also helping to develop and calibrate the infant’s immune system.

B. infantis is far more abundant in human milk than in the milk of cows or even chimpanzees. Preliminary speculation suggests that this difference arises because B. infantis facilitates brain development.

HMOs also block the actions of various pathogens: Salmonella, Listeria, Vibrio cholerae (cholera pathogen), Campylobacter jejuni (common cause of bacterial diarrhea, deadly to infants), some virulent strains of Escherichia coli (cause of neonatal meningitis, Crohn’s disease, etc.), and more. Apparently, a good reason to have so diverse an array of HMOs is to target different pathogens. Breast milk also offers infants “a starter pack of symbiotic viruses . . . . phages [stick to mucus 10×] more efficiently if there’s breast milk around” (p. 97). Really, breast milk offers a starter kit for the infant’s entire microbiome and immune system.

Figure 09. This mama Allen’s Swamp Monkey (at the San Diego Zoo) offers her infant not only key nutrients, but also “a starter pack” of symbiotic microbes with a passel of indigestible microbe food, ensuring that her baby’s gut microbiome will have a healthy start.

After humans are weaned, we must continue to nourish our own microbiomes, partly by providing a diet rich in foods that our microbes consume. By providing a varied diet, we’re ensuring the biodiversity of our microbiome.

5. In Sickness and in Health, 103–141

“Corals are animals with soft tubular bodies crowned by stinging tentacles. You rarely see them like this because they hide in limestone which they secrete themselves. . . . play home to countless marine mammals. . . . Corals have been building reefs for hundreds of millions of years” (p. 104). Corals rely on microscopic algae to survive. “Every square centimetre of their surface contains 100 million microbes, more than ten times as many as on a similar patch of human skin or forest soil” (p. 105). One of the many ways that benign microbes aid corals is by occupying space so that malignant microbes don’t have room. Algae also feed the corals they occupy.

Medium-sized herbivorous fish keep the algae in check by grazing on it. Sharks and larger fish keep the grazers in check. When humans kill most of the grazers, the algae goes bonkers and grows excessively, and the ecosystem goes out of whack, killing the coral, its grazers, and the fish and sharks who eat them. This situation is dysbiosis, the inverse of symbiosis.

By studying microbe-free mice in sterile environments, researchers can see how dysfunctional their digestive and immune systems are. A healthy microbiome is essential to a healthy immune system and digestive system. Researchers have also manipulated the microbes of rodents to create fat rodents or lean rodents. Obesity appears to be linked to the microbiome.

On the other hand, the microbiomes of malnourished children are impoverished. Children with nutrient-poor diets develop dysfunctional microbiomes, which inadequately extract nutrients and energy from the foods they eat. When their diets are supplemented, they temporarily thrive, but those effects are short-lived unless they continue to receive food with supplemental nutrients. Early malnutrition seems to cause long-lasting damage to the child’s microbiome, which supplemental nutrition relieves only temporarily.

Yong suggests that our microbiomes have an “immunostat,” similar to a thermostat, which adjusts our immune responses from hair-trigger to neglectful. According to Yong, our modern use of antibiotics, antiseptics, and processed foods disrupts the functioning of our immunostat, such that our immune system goes berserk over dust mites, pollen, and even our own beneficial microbes and our own cells, causing auto-immune disorders.

For instance, the autoimmune disorder inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) causes severe chronic diarrhea, as well as fatigue, weight loss, and pain. The two main types of IBD are ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, which can afflict young people, too. Studies of the microbiomes of IBD sufferers reveal them to be unhealthy — less diverse and less stable. They’re underpopulated by beneficial microbes and overpopulated by inflammatory microbes and other harmful species.

Other inflammatory diseases may also be linked to problematic microbiomes, such as type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, allergies (e.g., asthma), and more. Communities in which there are higher levels of infectious diseases seem also to have fewer chronic inflammatory diseases. Several factors seem to be correlated with lower numbers of microbes and higher rates of inflammatory diseases: smaller families (fewer siblings), urbanization, chlorination and sanitation of food and water, lack of contact with pets or livestock or other animals. Furry pets alone can make a difference. Homes “without furry pets were ‘microbial deserts’. Those with cats were far richer in microbes, and those with dogs were richer still” (p. 122).

Our introduction to healthy microbes begins at birth. Literally. During birth, as an infant passes through the mom’s vagina, her microbes colonize her infant. After birth, mom continues to supply her infant with microbes and with food for her infant’s microbes (described in the previous chapter). An infant born via Caesarean section and then fed with formula in bottles won’t benefit from these immediate boosts to its microbiome or to its immune system. If the infant goes on to eat a low-fiber diet with few fermented foods, it’s going to struggle to have a healthy microbiome. If the developing person is unlucky enough to contract an infection, it’s possible that yet another assault will reach its microbiome: antibiotics.

Figure 10. This lucky baby was born coated with her mom’s microbes, getting her off to a great start.

Many antibiotics have been and continue to be life-saving. Unfortunately, they are also overprescribed and needlessly prescribed, such as to treat viral infections that aren’t affected by antibacterial antibiotics. Even people who don’t consume antibiotics directly may still be consuming them indirectly. Since the 1950s, farmers have been giving their livestock low doses of antibiotics purely to prompt them to grow and fatten up more quickly. Anyone eating meat, milk, or other products from these medicated animals will also consume antibiotics, perhaps unwittingly. Another source of antibiotics is a variety of antiseptic products, from kitchen cleaners to hand wipes to personal hygiene, . . . and much more.

When comparing the microbiomes of people who live in WEIRD countries (Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democratic) with people who live in other countries (commonly called “developing”), WEIRD people have microbiomes that are far less diverse than other people. Some microbes in people from non-WEIRD countries don’t even exist at all in people from WEIRD countries. This shrinking of diversity may be linked both to eating less fiber in our diets, and eating fewer plants overall.

Yong and various microbiologists warn, however, that these findings are correlational, not necessarily indicative of causation. They urge greater research, using larger population samples, over longer time scales, and with greater scientific rigor. One thing is known, however. The diminution of microbial diversity should be a cause for concern. Its various causes mostly tie to human intervention and human actions. When considering the climate crisis, various kinds of pollution, habitat destruction, and so on, let’s also give a thought to the microbes.

6. The Long Waltz, 143–164

Because bacteria and other microbes are ubiquitous, it seems inevitable that we and other organisms will come into contact with new species of microbes, which may form new symbiotic relationships with us. We touch them (through casual or intimate contact), we inhale them, we consume them. “The average human swallows around a million microbes in every gram of food they eat” (p. 145). Some microbes more aggressively invade us, such as those that tag along when insects bite or parasites attack.

Just gaining entry is no guarantee of success, however. Myriad defenses deter microbes from settling down in a new host, not least of which is the host’s immune system. If the microbe provides a useful service, it’s more likely to be well received. For instance, a microbe that breaks down indigestible items into valuable nutrients may be welcomed, as might a microbe that attacks pathogens.

The Streptomyces bacteria are such powerful antimicrobial microbes that they’re the source two thirds of the antibiotics in use today. In the wild, beewolf wasps spread Streptomyces bacteria from their antennae to the cocoons of their growing grubs, to protect them from pathogenic fungi and bacteria. Their grubs grow into adults who do likewise for their offspring. Yong calls this generational transmission “the long waltz” (p. 148).

Generational transmission can occur through the cells of eggs, via microbes in the eggs’ mitochondria. Less directly, but just as effectively, a parent can coat the eggs with a dense microbial layer, or provide microbe-laden food packets for the larvae to eat as soon as they hatch. Tsetse flies gestate their larvae internally, feeding them nutrient- and microbe-rich “milk”; their live-born young are already fully equipped with microbes. Koala joeys, like other marsupial youngsters, suckle in the mother’s pouch for several months. As the joey is ready to be weaned to consuming eucalyptus leaves, it nuzzles up to mom’s rear end and laps up “pap,” specialized feces rich with microbes and nutrients to establish its microbiome.

Fun — but disgusting! — fact: Termites shed the lining of their gut every time they molt, so they regularly lick one another’s excrement to replenish it. Termites rely on microbial help to digest almost-indigestible wood. Other known coprophages (feces-eaters) are “cows, elephants, pandas, gorillas, rats, rabbits, dogs, iguanas, burying beetles, cockroaches, and flies” (p. 151).

Figure 11. This koala mom cherishes her joey and has doubtless provided her joey with pap, which “contains up to 40 times more microbes than regular faeces” (p. 150; photo taken at the San Diego Zoo). A perfect way to initiate her baby’s microbiome.

Human infants don’t get the benefits of pap, and we don’t supply our developing fetuses with microbes in the uterus. During birth, however, the human newborn passes through a microbe-dense vagina, bathing in microbes as it progresses through the birth canal.

An easier way to acquire microbes is through skin contact, which commonly occurs among animals who live in close quarters, such as baboons, salamanders, bluebirds, and humans. Among roller-derby teams, each team has distinctive microbial communities, but during a contest, opposing teams share microbes. Though we are accustomed to think of these exchanges as a mode of transmitting pathogens, it’s far more common to exchange beneficial microbes.

In addition, our bodies are inhospitable to most microbes, so only a small proportion manage to find a home in our microbiome. For instance, among the hundreds of groups of bacteria extant, almost all of the bacteria in our gut come from just four groups of bacteria.

Among the many concepts introduced by iconoclastic biologist Lynn Margulis, at least two concepts (and terms) are key to microbiology: endosymbiosis and holobiont. Through endosymbiosis, microbes can become a permanent part of an organism. For instance, when bacteria were incorporated into mitochondria, the microbes were no longer free floating; they were forever embraced within the confines of the mitochondria.

The term holobiont refers to the whole comprising an organism and the symbiotic microbes within it. You and your resident bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms make one complete holobiont. Corals, their algae, and their microbial communities comprise an interdependently symbiotic holobiont. To understand and protect corals requires viewing them as holobionts, not as discrete animals.

Eugene Rosenberg and Ilana Zilber-Rosenberg go beyond this concept to consider the genome of an organism in terms of its hologenome — that is, the host organism’s DNA, along with the DNA of all the microbes within the host organism. They noted that the hologenome must also be considered when viewing natural selection. Natural selection can occur because (1) individuals vary (and therefore can offer various traits to be “selected”), (2) these variations can be inherited (and therefore can affect future generations), and (3) the variations differ in terms of adaptive fitness, their suitability for helping the individual survive to reproduce forthcoming generations. To the Rosenbergs, the hologenome affects natural selection, not just the organism-specific genome. For instance, a termite that can digest wood because of its microbiome is more fit to survive than a termite lacking microbes for digesting wood.

Further modifications of the hologenome concept note that not all of the microbes in a microbiome are essential to the host organism’s viability and fitness. Some may be bystanders having little effect, and some may even be harmful but not harmful enough to undermine adaptive fitness. An organism’s microbiome may affect its preferred diet, its smell and other traits, and its sexual attractiveness to other organisms. It’s possible that microbiome changes may even lead to speciation, such that a single species may eventually become two separate species, with distinct habitat, diet, and mate preferences. Lynn Margulis called this process, by which symbiotic organisms can spawn new species, symbiogenesis.

7. Mutually Assured Success, 165–189

Fun quote: “I’m standing in a room the size of a small garden shed. There’s enough room to swing a cat, just, but you’d get claw-marks on the walls” (p. 165).

True bugs, the insect class Hemiptera, include a large group of sap-sucking specialists who need symbiotic bacteria in order to extract nutrients from plant sap. In fact, these bugs — such as aphids — are the only critters who dine exclusively on plant sap, and they can do so only because their guts contain specialized microbes. There are “around 82,000 species of hemipterans,” including “5,000 species of aphids, 1,600 species of whiteflies, 3,000 plant lice, 8,000 scale insects, 2,500 cicadas, 3,000 spittlebugs, 13,000 planthoppers, and more than 20,000 leafhoppers” (pp. 166, 169). Clearly, their strategy for success has worked.

As an example, aphids feed on phloem sap, which travels through an inner layer of plant stems, transporting sugary fluids throughout the plant. Phloem sap offers plenty of energy but lacks many key nutrients, including the essential amino acids needed for animals to live. Aphids rely on their symbiotic bacteria — mostly Buchnera bacteria — to produce these key nutrients for their survival. Because the production of amino acids is so complex, requiring numerous different enzymes at different phases of the process, the aphids and the bacteria must cooperate to build these amino acids. The aphids and their bacteria have a mutually interdependent symbiotic relationship.

For more on aphids, as well as honeydew, ants, trees, and ladybugs, please see my blog https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/15/the-secret-network-of-nature/#5 ; in addition, my blog on insects, https://bird-brain.org/2025/08/21/life-on-earth-insects/ also discusses aphids, regarding their reproduction, their relationship with wood ants, and the Hemiptera class of bugs. Other sap-sucking Hemipteran bugs have similar mutualistic symbiotic relationships to produce these essential amino acids. So do other insects, such as carpenter ants (with about 1,000 species, all of which carry Blochmannia symbiotic bacteria).

Figure 12. Pines and other trees are often plagued by sap-sucking insects.

In places where no trees can be found — and really, where no plants can be found — life still finds a way, especially when organisms can form symbiotic relationships with microbes. About 1 ½ miles down in the ocean, giant tube worms can survive beneath the weight of the entire ocean, in deep-sea vents, rich in hydrogen sulphide. There, the lightless environment can reach incomprehensible temperatures of 752º F. (400º C). Close examination of one of these worms revealed that it had no mouth, no gut, no anus. Instead, it contained an enormous trophosome filled with pure crystalline sulphur. Weird! It turned out that the trophosome was also jam-packed with bacteria — about 1,000,000,000 bacteria for every gram of trophosome tissue. The bacteria were able to use enzymes to convert sulphide compounds into food for the tube worms. Mind-boggling to the researchers studying it at the time.

In sunlit environments, plants, algae, and some bacteria can use solar energy to convert carbon dioxide and water into sugary food — photosynthesis. A byproduct of photosynthesis is oxygen, which the photosynthesizers release. Far away from the sun, where photosynthesis is impossible, chemosynthesis offers another way to make energy to fix carbon for food. In the tube worm’s deep-sea vent, Riftia bacteria are able to oxidize the vent’s sulphides for the energy needed to fix carbon. For Riftia, the by-product of chemosynthesis is pure sulphur, which then accumulates in the trophosome of the tube worm.

Tube worms aren’t alone. Numerous other animals (e.g., clams, worms, snails) living in the deep sea also rely on microbial symbionts to survive. Though chemosynthesis is necessary in the deep sea, it also can occur in other locations, sometimes alongside photosynthesis, or just beneath the surface, such as among worms living beneath the mud in shallow waters.

For some microbiologists, the challenge isn’t getting into remote locations to study organisms, but rather dealing with bureaucratic headaches in gaining access to needed samples. Nonetheless, Ruth Ley managed to collect stool samples from a wide array of zoo animals. By studying the gut microbes in the poop of a wide array of animals, she discovered that for the most part, “plant-eating herbivores typically had the highest diversity of bacteria. The meat-eating carnivores had the lowest. The omnivores . . . were in the middle” (p. 176).

It turns out that meat eaters don’t have to do as much digestive labor to harvest nutrients from their food. Plant eaters have to work harder to extract nutrients from their food. Plant tissues contain fibrous complex carbohydrates that are hard to digest, such as cellulose, lignin, and others. Animals don’t have the array of enzymes needed to break down these tough fibers. Bacteria do. We humans have about 100 fiber-digesting enzymes; just one common human gut bacterium — Bacteroides thetaiotamicron, aka B-theta — has more than 250 such enzymes, and it’s certainly not alone. Cows and sheep derive 70% of their energy from the nutrients made available by their microbiome.

The first animals were meat-eating insects, so they didn’t need much help extracting nutrients from their food. Being a strict carnivore limits both your diet and your habitat, though. By adapting to be able to eat plants, animals could spread more widely and eat a more varied diet. But doing so meant gaining the aid of microbes.

Getting help from microbes meant doing more than simply swallowing microbes along with the plants. Many herbivorous mammals rearranged their digestive tracts to make room for microbes to do their work. They needed a bigger gut and specialized fermentation chambers in their guts, to allow food to progress more slowly. Hindgut fermenters — elephants, rhinos, horses, gorillas, and so on — located the specialized chambers at the distant end of their gut. Foregut fermenters — giraffes, kangaroos, sheep, cows — located the specialized chambers closer to the stomach, sometimes even preceding it. Ruminants added an additional aid to digestion: chewing and swallowing the food, regurgitating it, chewing it again, then swallowing it again. Each type of herbivore has a different array of microbes, and these microbes differ across species, too.

Insect herbivores have different ways of handling plants as foods, but they still rely on microbes to do so. Termites stand out among herbivores. Among some termites, their microbes — mostly protists (eukaryotic microbes) — “make up half the weight of their termite host . . . . [because] they have enzymes that digest the tough cellulose in the wood that termites eat” (p. 179). Not all termites rely on microbial protists; some termites house bacteria in a series of stomach chambers, reminiscent of cow stomachs.

A third group of termites has an even more sophisticated way of handling food. To begin with, they farm fungi in their ginormous mound nests, feeding the fungi bits of wood scraps. The fungi break these scraps into tinier bits, which the termites eat. Then the termites’ gut bacteria further break down the teensy wood bits. Without both the fungi and the gut bacteria, these termites (and their egg-producing queen) would starve.

Seasonal changes also affect animals’ microbiomes. For instance, the diet of howler monkeys changes dramatically across the year. For about half of the year, they eat mostly easily digestible high-calorie fruits, such as figs. When the fruit are all gone, though, they have to switch to hard-to-digest, low-calorie leaves and flowers. To accommodate these dietary changes, the monkeys’ gut microbes change, too. During the lean months, their gut microbes must work hard to extract enough nourishment for the monkeys to survive. Actually, many animals undergo seasonal changes in diet and in gut microbiomes. Even in our modern environments, we may eat more fruits and salads during the summer and more soups and cooked foods during the winter.

Figure 13. Acorn Woodpeckers, many other birds, and many other animals have to make adjustments to seasonal changes in their diets. These changes mean that their gut microbes must change, as well.

Many plants mount chemical defenses against herbivore assaults, producing toxins of varying degrees of lethality, in varying amounts. Tannins are among the most abundant of these. Many herbivores are at least somewhat deterred by plant toxins, but some have equally potent microbiomes able to detoxify the plant toxins. Desert woodrats munch on creosote bushes, reindeer nibble on lichens, koalas snack on tannin-rich eucalyptus leaves, and so on. Unfortunately for some plants, the detoxification truly threatens the lives of trees and even of forests, such as the mountain pine beetles, whose microbiome makes it easy for these beetles to devastate entire forests.

8. Allegro in E Major, 191–210

Unlike us vertebrates, bacteria freely swap bits of DNA with their neighbors. They’ll also take up random bits of DNA floating in their environment. They’ll even use nearby viruses to move DNA from cell to cell. These frequent swaps are horizontal gene transfers, unlike the vertical gene transfers that occur from parent to offspring.

These constant swaps of DNA can transform a benign bacterium to a dangerous pathogen — and vice versa. Such swaps facilitate the rapid evolution of bacteria for adapting to a changing environment. The acquired genes can resist antibiotics, create stronger defenses, find new sources of energy and other resources, and so on.

Vertebrates and other non-microbial organisms can’t adapt nearly as quickly. If one vertebrate develops a distinctive genetic adaptation, it may take many generations for that beneficial adaptation to become widespread. Except — sometimes, vertebrates can acquire beneficial adaptations by acquiring new symbiotic microbes. Such microbes might help them to absorb nutrients from a new food source or to adapt to a new habitat. For instance, in Japan, people developed the ability to digest and absorb nutrients from otherwise indigestible seaweed, marine algae, by acquiring bacteria that could break down the seaweed in the gut microbiome of Japanese people.

Occasionally, acquired microbes migrate into the DNA of the organism hosting the microbes. Among insects, about 20–50% of insect species may have incorporated microbial DNA into their own DNA. Recruitment of microbial DNA has increased the dangers of some pests, such as coffee berry borer beetles, parasitic wasps, and even nematode worms. To combat parasitic pests, other invertebrates have recruited microbe-killing bacteria into their own genomes. These invertebrates include arachnids such as mites, scorpions, and ticks; and marine invertebrates such as sea anemones, oysters, water fleas, limpets, and sea slugs.

Some invertebrates host bacteria, which also host bacteria inside them. So the microbial symbionts host their own microbial symbionts. Yong describes them as “a living matryoshka doll” — Russian nesting dolls. In these situations, these collaborative symbionts work together to achieve goals, such as making a complex amino acid. For instance, to make phenylalanine, nine enzymes are needed. No one symbiont has all the needed enzymes, but a trio of symbionts — two bacteria and their host — has all nine, thereby creating the needed nutrient.

Figure 14. Microbes can nest within microbes, within their host organisms, similar to these matryoshka dolls.

Over time, these mutual interdependencies can lead to each participant losing genes that duplicate the genes of other participants. Occasionally, a symbiont can break down so much that it leaves some of its genes inside the organism but ceases to exist altogether as a separate entity. In one mealybug species, researchers found genetic remnants of five bacteria, but only two bacteria remained alive. The other three bacteria had contributed their DNA but ceased to exist as individual bacteria. The genetic remnants continued to serve important roles, such as in making amino acids and other molecules.

Some microbial symbionts are occasionally present and occasionally absent from particular hosts. For instance, aphids host four bacteria species, three of which are sometimes there and sometimes not. It turns out that these three bacteria are great at defending the aphids against parasitic wasps, but in the absence of parasitic wasps, the aphids dumped the unneeded microbes. With further research, they found aphids hosted up to eight extra bacteria, which might serve various roles: defending against parasitic wasps, fungi, and other threats; adapting to high heat; changing color (for camouflage); changing diet; and so on. At least one virus was also useful to its aphid host. As their environment or habitat changes, so do their microbial symbionts. Though hosts can’t themselves change their genetics quickly, they can adapt more quickly by changing their microbial symbionts. Generally, it’s pure luck that we acquire these beneficial microbial symbionts. We rarely — if ever — know what we’re doing.

9. Microbes à la Carte, 211–249

Because microbiomes are in a constant state of flux, microbiological researchers see opportunities to change — or at least influence — the microbiomes of humans and other animals for the better. For instance, millions of people suffer greatly from a devastating disease caused by three species of nematodes — filiarisis, one form of which is elephantiasis, which is as grotesque and painful as it sounds. All three nematodes, and a fourth related disease-causing nematode, have microbial symbionts on which they rely for causing parasitic diseases and even for living. Direct medication assaults on the nematodes don’t work because of the lingering effects of the nematodes’ symbionts. Researchers now feel hopeful of finding a cure by seeking ways to target the microbial symbionts, thereby killing off their partner nematodes.

Other researchers are looking for ways to restore damaged or disrupted ecosystems by introducing microbial symbionts to new hosts within those ecosystems. Still others are hoping to forge new symbiotic relationships, developing “cocktails of beneficial microbes that we can take to correct and forestall illnesses, packages of nutrients that will feed those microbes, and even ways of transplanting entire communities from one individual to another” (p. 215).

Rather than focus solely on removing or debilitating pathogens, some researchers are looking for ways to add beneficial microbes. Easier said than done. Ecosystems are complex, and so are microbiomes. Adding an organism here, subtracting an organism there, . . . unexpected consequences seem almost inevitable. Researchers might add a beneficial organism, only to find that it outcompetes an existing beneficial organism or has a secondary undesirable effect. Wipe out a harmful microbe, only to make way for an even more devastating pathogen. Plenty can go wrong.

Nonetheless, desperate times call for desperate measures. When species of amphibians seemed on the precipice of extinction due to a deadly fungus, researchers tried introducing an antifungal bacterium to a sample group of salamanders, and the experiment worked. Next, they tried introducing the bacterium to endangered frogs, with the same delightful life-saving results. Success. Now . . . how to introduce these bacteria to a larger population of amphibians . . . . One possibility is to spread out doctored soil. This tactic seemed to work well in one population, but then when it was tried in a separate population, it failed. Bummer. More research is needed, with an awareness that what works well in one ecosystem may fail entirely in another.

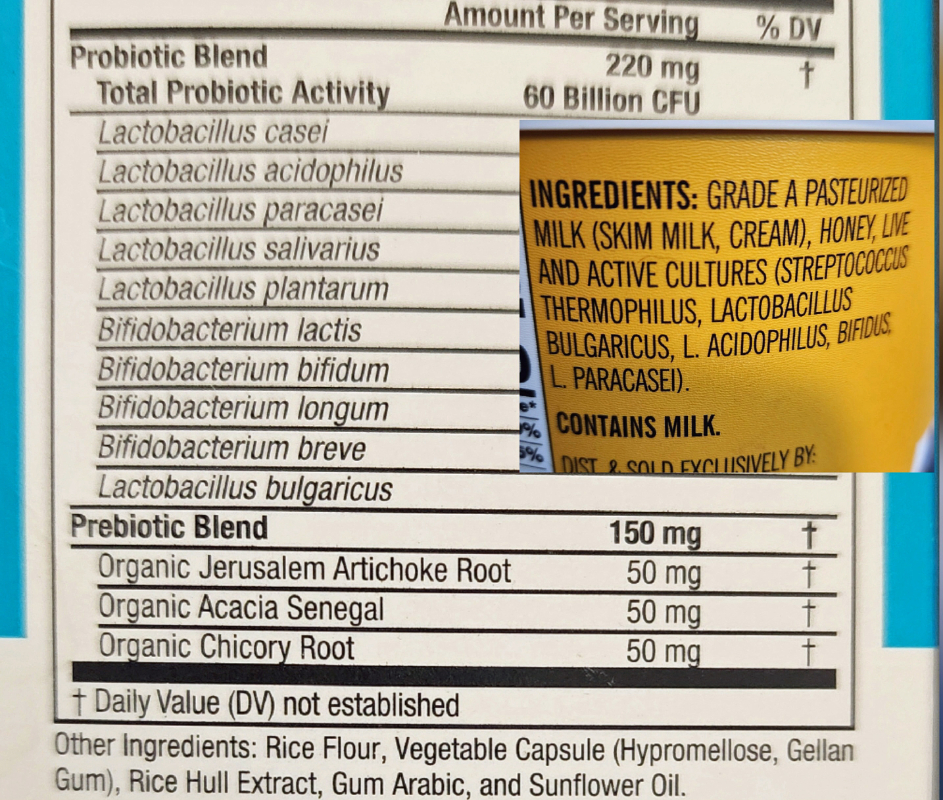

Whereas antibiotics are intended to remove bacteria (and often other microbes) from our microbiome, probiotics are intended to add bacteria to our microbiome. Unfortunately, that, too, is not so simple. Our gut microbiome is designed to bar new, unfamiliar bacteria — which is usually a good thing, but which means that trying to add probiotics to our microbiome is unlikely to succeed. Though the probiotics industry currently is a multi-billion-dollar industry, most manufactured probiotics show little or no success in making a home in our gut microbiomes — fleeting success, at best. Yong said, “They’re like a breeze that blows through two open windows” (p. 222).

Figure 15. It was easy to find probiotics at my home. In my fridge is yogurt containing 5 bacterial strains, and in my medicine cabinet are pills packed with 10 bacterial strains, which my own doctor suggests taking whenever she prescribes antibiotics. I guess I shouldn’t count on many beneficial effects, but they don’t seem to do any harm either.

Even so, they can sometimes help, to a modest degree, for a short time, and sometimes, that’ll do. For instance, probiotics can shorten bouts of diarrheal infections, and they can reduce the risk of diarrhea resulting from taking a course of antibiotics. Little or no evidence supports the suggestion that probiotics can help to treat asthma, eczema, and other auto-immune disorders, or diabetes, or other diseases believed to have links to the microbiome.

Despite the lack of evidence supporting the use of commercially sold probiotics, the underlying idea of probiotics still sounds promising. Given the vital role of our microbiome, it seems highly likely that there should be some way to provide beneficial microbes to enhance its function. We just haven’t found the right microbes, for the right people, at the right time, using the right methods of introducing these probiotic microbes. Another cautionary note bears mentioning, though. Microbes can have powerful, unexpected consequences. Introducing the almost-right microbe at the almost-right time, using the almost-right method could lead to unwanted, or even harmful, outcomes. Sometimes, even the right microbe can have harmful outcomes, as well as positive ones, such as the benefits of Helicobacter pylori for protecting against esophageal cancers, yet causing ulcers and stomach cancers.

Even if the newly introduced microbe can manage to resist assault by other microbes, it still needs something to eat that’s abundant enough that the new microbe doesn’t deprive existing beneficial microbes of the food they need to thrive. In line with the term probiotics (the microbes we introduce to our microbiome), the term for the fibrous plant-based foods we provide to our microbes is prebiotics.

Recall that human breast milk comes ready-made with both probiotics and prebiotics for the infant’s microbiome. In some hospital neonatal units, premature infants have been given infusions of probiotics to try to help them avoid some of the hazards of preterm birth related to their lack of a healthy microbiome. Such regimens are even more successful when probiotics are combined with breast milk, providing both the prebiotics and the probiotics to boost the neonatal microbiome.

Other studies of probiotics have found that while providing one species of microbe might be beneficial, probiotics are far more likely to be successful when offered as a community of microbes, with multiple strains of a single species or even with multiple species. A more adventuresome technique for infusing probiotics is to provide a fecal microbiota transfer (FMT), which is exactly what it sounds like. A stool sample is taken from a prescreened donor, scrutinized, then infused (through the rectum, NOT orally), all under close medical supervision. Some FMTs have shown remarkably good results. Yong noted, “There’s no such thing as alternative medicine; if it works, it’s just called medicine” (p. 231).

To facilitate success, two different strategies have been used: (1) Pretreat the recipient with antibiotics, to wipe out the recipient’s existing gut microbiome, to better receive the FMT; (2) pretreat the recipient with a prebiotic diet, so the recipient’s microbiome will more readily help the new microbes make a home there. Thus far, the most effective uses of FMT have been to combat antibiotic-resistant infections by Clostridium difficile, aka C-diff.

Essentially, an FMT is an ecosystem transplant. Many attempts to use FMT for treating a variety of ailments have proved disappointing. Also, the possibilities for harm should serve as a warning not to do so without careful medical scrutiny. In addition, little is known about any long-term effects of using FMT. Some studies have been examining the use of freeze-dried feces capsules, but without careful medical supervision, such uses are iffy, at best, and possibly harmful. Custom-made, bespoke FMTs are more likely to lead to positive outcomes than mass-produced, generic FMTs.

Figure xx: Were you worried that I might try to illustrate FMT? I won’t. Whew!

Many medications (e.g., digoxin, for heart ailments; statins, for high cholesterol) don’t work in people whose gut microbiomes lack particular microbes or enzymes. For these people, it’s possible that the medication might be made effective if accompanied by an infusion tailored to that individual’s microbiome. For such methods to work, an analysis of the person’s genome and microbiome are needed. Piecemeal approaches will usually fail.

In the future, more cutting-edge ways to study the microbiome may become available: Engineer particular bacteria to pass through the gut microbiome, looking for problems, and reporting back on their findings. Even more futuristic: Engineer microbes not only to find problems, but also to fix them. Such engineering tricks offer lots of hope, but also notes of caution. When fixing one problem, might a microbe cause another, or at least weaken other healthy microbial processes?

One researcher has suggested that when engineering microbes, the engineers should build in a “kill switch,” to turn off the actions of the microbes, as desired. That’s particularly important when viewing engineered microbes within a community context. If a microbe recipient develops a high-potency pathogen as a result, could that person communicate that pathogen to vulnerable members of the person’s community? Or even cause a pandemic?

On the other hand, can researchers prevent the spread of infectious diseases by altering the genomes of pathogens, such as the virus that causes dengue fever? Some researchers are investigating whether they can use bacteria to prevent mosquitoes from spreading this virus. Similar strategies might be used on the mosquitoes that carry malaria pathogens or the pathogens that cause yellow fever, Zika, or Chikungunya. The possibilities may offer some hope of combating these cruel diseases, though the research has been challenging and has faced numerous obstacles and failures. Nonetheless, preliminary research, with community buy-in, has shown promise in preventing the spread of dengue fever.

Figure 16. This tiny insect, a female Aedes mosquito, comes from a long line of deadly killers, who spread lethal yellow fever and numerous other infectious diseases. Researchers are looking for microbial solutions to keep these mosquitoes (and other disease vectors) from killing more humans and other animals.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mosquito; Description: Ochlerotatus notoscriptus, Tasmania, Australia; Date: 16 October 2009; Author: JJ Harrison (https://www.jjharrison.com.au/). This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. You are free: to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work, under the following conditions: attribution – You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

10. Tomorrow the World, 251–264

“All of us are constantly seeding the world with our microbes. Every time we touch an object, we leave a microbial imprint upon it. Every time we walk, talk, scratch, shuffle, or sneeze, we cast a personalised cloud of microbes into space. Every person aerosolises around 37 million bacteria per hour” (p. 251). “Within 24 hours of moving into a new place, we overwrite it with our own microbes, . . . [we literally] make [ourselves] at home” (p. 252). All who share a living space — or workspace or other space — constantly exchange microbes, taking some and leaving others.

Fun(?) fact: When a public restroom is cleaned, the first bacteria to accumulate are fecal bacteria, but these are soon outnumbered by skin microbes. So, actually, a newly cleaned public toilet has relatively more fecal bacteria than one that hasn’t been cleaned in awhile.

Slightly more fun fact: A hospital room with an open window will have relatively fewer pathogenic microbes than a room with no access to outdoor air, even if the hospital’s ventilation system is superlative. Florence Nightingale, renowned nurse of the Crimean War (1853–1856), noticed that her patients recovered from infections more quickly if she opened a window in their room. If you think about it, it makes sense to bring in more harmless microbes from the outdoors, replacing some of the pathogenic microbes indoors.

Figure 17. In the mid 1800s, among the many innovations that Florence Nightingale introduced to the field of nursing was her observation that patients recovered from infections more readily when a window was open, rather than closed.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence_Nightingale . Photograph by Henry Hering (1814–1893); Date, circa 1860; Source: NPG x82368 from National Portrait Gallery, London; Licensing: Public domain. The author died in 1893, so this work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1930.

Some architects and designers are thinking about “bioinformed design” of buildings. Among the many ideas being put forth are designing a ventilation system that routinely flows through a wall of plants. Some designers are considering purposefully including microbes to occupy the space, though that seems a bit tricky, given that microbes constantly adapt and change, possibly not in desirable ways.

On a smaller scale, designers are looking for ways to include antifungal bacteria in designs of homes in flood-prone areas, to minimize problems with mold. There may be valuable applications of microbiology for waste-treatment plants and for contaminated lakes, oceans, rivers, wetlands, and other waterways. Microbiology may lead to better treatments for allergies, including food allergies and allergic reactions to bug bites. Study of gut microbiomes may lead to effective prevention or treatment of myriad diseases and disorders, from obesity to asthma.

Another area of research being studied is forensic microbiology — such as investigating microbes to track where perpetrators and victims may have been and may have gone. A more ambitious use of microbiology is to study the microbiomes of individuals within an array of ecosystems, to better understand what is working well, what isn’t working well, and what might be done to make improvements. Perhaps one of the best possible outcomes is simply to better understand our world and the amazing microbes living in it.

[Back matter]

- Acknowledgements, 265–267

- Notes, 269–297

- Bibliography, 299–338

- List of Illustrations, 339–340

- Index, 341–357

Text and photos by Shari Dorantes Hatch, unless otherwise indicated.

Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment