The more I discover about insects, the more fascinating they become. Insects provide vital services to our living planet, to the diverse ecosystems they inhabit, and to humans. Let’s try to be kind to them, too.

Contents

- Living Organisms on Earth

- Arthropods

- Characteristics of Arthropods

- Categories of Arthropods

- Insects

- Body

- Physiology — Circulation and Respiration

- Physiology — Digestion

- Physiology — Nervous System and Sensations

- Reproduction and Development (and Metamorphosis)

- Success of Insects

- Insect Resourcefulness

- Importance of Insects

- Pests

- Helpers

- Insect Predators and Prey

- Decomposers

- Pollinators

- Seed Dispersal

- Soil Protection and Creation

- Symbiotic Relationships

- Foods

- Useful Products Provided by Insects

- Useful Services

- Insect Behavior — Locomotion

- Insect Behavior — Sociality

- Insect Behavior — Communication

- Insect Behavior — Diet and Foraging

- Insect Behavior — Defenses

- Threats to Insects

- Helps to Insects

- Insect Diversity

- A Few Specific Insect Families and Genera

- Biophilia, Love of Nature

- Resources

- Books

- San Diego Zoo Resources

- Wikipedia

- Other blogs by me

Living Organisms on Earth

The two major groups of living organisms are prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea) and eukaryotes (plants, animals, fungi, and all the rest). The major distinction: Each eukaryote cell has a nucleus surrounded by a membrane, whereas prokaryote cells don’t. Prokaryotes are far more numerous than eukaryotes, but the global biomass of eukaryotes (468 gigatons) is many times larger than the biomass of prokaryotes (77 gigatons). (Plants make up a smidge more than 80% of Earth’s biomass.)

Among animals, 95–97% of all animal species are invertebrates, including a wide diversity of species. For instance, in terms of size, invertebrates range from 0.0004 inches (some myxozoans, aquatic parasites) to the colossal squid, up to 33 feet long.

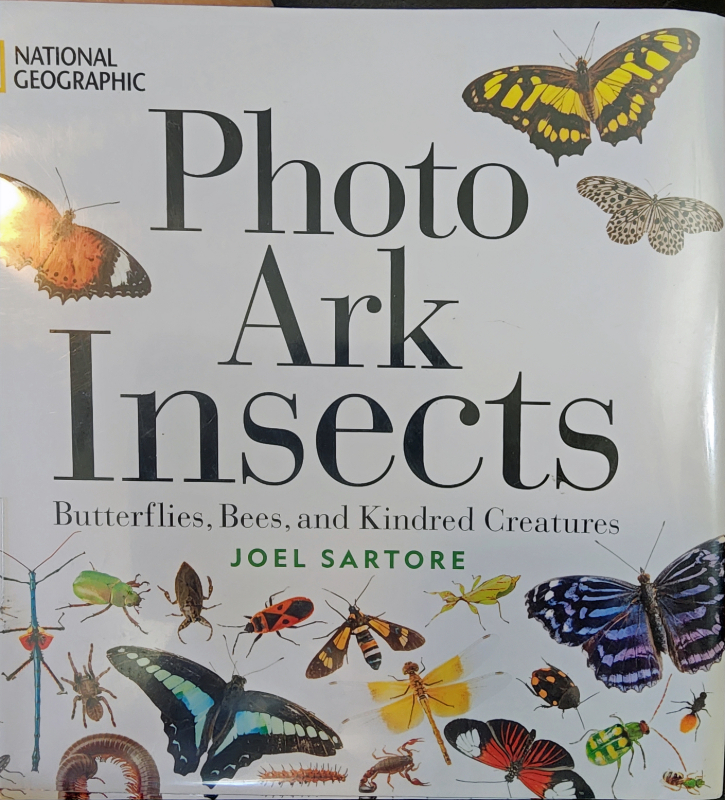

Figure 01. I realized that my ignorance about insects was just too vast; I needed to learn more about insects. Of the books I checked out from the San Diego Public Library, this translated book by Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson, Extraordinary Insects: The Fabulous, Indispensable Creatures Who Run Our World, is a gem. The other three I found were great fun, but between Anne and a gazillion Wikipedia pages and even my own blogs, I found the information I wanted. I’m now slightly less ignorant than I was.

Arthropods

Among invertebrates, arthropods comprise about 2–10 million species — the most numerous of all phyla of animals, 80% of all known animal species.

Characteristics of Arthropods

Body Segments, Jointed Appendages

At some time in their lives (typically, as adults), arthropods have segmented bodies. These segments are built as modules, such as the head — attached to, yet distinct from, the rest of the body. All adult arthropods also have two or more pairs of jointed appendages (insects, three pairs; spiders, four pairs; millipedes, many pairs).

Figure 2. Like other arthropods, this spider has a segmented body and jointed appendages.

Exoskeleton and Molting

In addition, adult arthropods have an exoskeleton, an external armor giving their bodies structure and protecting their soft internal body parts. A waxy layer covers the hard exoskeleton, protecting the insect against dehydration. The exoskeleton also protects the limbs, typically jointed legs and often wings.

The rigidity of the exoskeleton means that as the arthropod grows larger, it must molt — break free from its existing exoskeleton — and create a new, larger exoskeleton. To do so, beneath its existing exoskeleton, the arthropod uses chitin (a highly modifiable glucose-based secretion) to produce a new exoskeleton. Once the new exoskeleton is complete, the arthropod cracks open and breaks free from the old exoskeleton, enclosed in its new one. The arthropod must puff itself up as big as possible, so that by the time the new exoskeleton has dried and hardened, it is as large as it can be. While the arthropod is growing rapidly, molting occurs repeatedly, but once it reaches full size, it stops molting.

Other Arthropod Features

Each arthropod also has a nerve cord running down the front of its body (below its gut). The cord connects to the arthropod’s brain, in its head, typically above and around its esophagus.

Along its back, its heart is a muscular tube moving hemolymph, a bloodlike fluid, through its body. The arthropod’s distinctive “open circulatory system” doesn’t contain blood vessels. Instead, the hemolymph flows directly into and around the body tissues, bathing them in oxygen and nutrients. The arthropod’s movements also facilitate the movement of hemolymph.

Categories of Arthropods

Living arthropods are categorized as

- Chelicerates (arachnids such as spiders, scorpions, vinegaroons, mites, as well as horseshoe crabs and sea spiders), which have chelicerae, two appendages located either above or in front of the other mouthparts, often specialized as fangs or pincers; among spiders, they may contain venom for injecting into prey

- Myriapods (millipedes, centipedes, and so on), which have numerous body segments, each of which has one or two pairs of legs (centipedes, one pair; millipedes, two pairs)

- Pancrustaceans (crustaceans, hexapods such as insects, isopods such as woodlice, and barnacles and other aquatic species), which have biramous limbs — with two branches per limb, each branch comprising a sequence of attached segments

Among pancrustaceans, hexapods (having six legs) are the most numerous, and insects are the most numerous of hexapods.

By the way, I’m thinking that spiders, and perhaps other arachnids, deserve a blog all their own. Please let me know what you think of the idea.

Insects

So, insects are eukaryotes → animals → invertebrates → arthropods → pancrustaceans → hexapods.

What makes an insect an insect?

- 3-part body — head, thorax, and abdomen

- 3 pairs of jointed legs, which all attach to the thorax

- compound eyes (almost always)

- a pair of antennae (almost always)

- 0–2 pairs of wings — the only arthropods who have wings

Figure 3. This insect has three segmented parts: a head, a thorax, and an abdomen; three pairs of jointed legs attached to its thorax; and a (tiny) pair of antennae. I’m guessing that this is an Eleodes armata beetle, so its pair of hardened forewings are shielding its pair of hindwings. (I’m really just guessing at the species, based on its appearance. I would welcome your corrections or other ideas.)

Body

Head

In general, the head is the sensory processing center for the insect, where its eyes (usually compound), mouth, and antennae are typically located. There are exceptions to eye locations, however. For example, in swallowtail butterflies, their eyes are geared to reproduction: In males, eyes are on the penis; in females, eyes are on her rear-end oviduct (for laying her eggs).

Thorax

The insect’s thorax is transportation central, where all three pairs of legs are attached, and where the wings — from zero to two pairs — are attached. The muscles to power these appendages are located in the thorax. For insects, wings aren’t modified leg limbs; they’re designed for flight.

Abdomen

The main functions of the abdomen are digestion and reproduction.

Physiology — Circulation and Respiration

Insect circulation isn’t distinct from other arthropods. Each has an open circulatory system, without blood vessels. It directly bathes its body tissues (legs and wings, too!) in hemolymph, moved around by its heart tube (located above its other organs), as well as by its own movements as it walks, flies, hops.

Insects don’t have lungs; instead, they breathe air through spiracles — small pairs of slits located along each side of their thoraxes and abdomens, opening into tracheal tubes and air sacs, which feed oxygen directly to their tissues. Insects can control the flow of air, adjusting the sizes of the spiracle openings to provide needed oxygen while avoiding dehydration.

Fun facts: Insect size is limited by their respiratory system. One writer described the insects’ breathing tubes as drinking straws. You can see how using spiracles to respire wouldn’t work well for huge insects. It’s thought that during the late Paleozoic era, when oxygen levels were higher, it was easier for large insects (such as dragonflies with 2-foot wingspans) to respire and to survive. One more cool fact: Madagascar Hissing Cockroaches use their spiracles to make their namesake hisses.

Physiology — Digestion

Insects are quite varied and have varied digestive systems, and even the same insect species may have a completely different means of digesting food at different times in its life cycle. Nonetheless, they do have some commonalities. All insects have mouths at some point in their life cycle. In their mouths, they mix their food with saliva they produce in salivary glands. Their saliva contains enzymes that start breaking down the food.

Flies expel digestive juices onto their food, pre-digesting it before slurping it up (more about flies later). Most other insects start to digest food in their mouths but finish doing so in their guts (located in the abdomen). After adding the enzyme-rich saliva to food in their mouths, they pass it to the crop, where it may be stored. From the crop, the food goes to the midgut, which does most of the digesting work. The midgut is lined with microscopic microvilli, which increase its surface area and which absorb nutrients from the food. From the midgut, any undigested food goes to the hindgut, where most of the remaining water is absorbed, and uric acid is added to the dried remains to create tiny pellets of fecal matter. Some other processes are involved, but this is the basic process for most insects.

Physiology — Nervous System and Sensations

Like other arthropods, each insect has a nerve cord extending down the front of its body (below its gut), with connections to sensory receptors in each joint of each of their limbs. In some situations, the sensory receptors in the joints can respond directly to stimuli. The nerve cord leads to the insect’s brain, located in its head. Its brain processes all the incoming information from its senses — sights, sounds, smells, touches, tastes, and more.

Intelligence

Probably few people would credit insects with great intelligence, but given how well insects have adapted to a wide array of habitats (deserts, caves, ponds, tundra), we may need to reconsider that belief. According to Wikipedia, intelligence “can be described as the ability to perceive or infer information and to retain it as knowledge to be applied to adaptive behavior within an environment or context.” Sounds like insects to me!

Sense Organs

In three previous blogs, I discussed Ed Yong’s An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/20/sensational-animals-part-1/ , https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/24/sensational-animals-part-2/ , https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/27/sensational-animals-part-3/), which cited numerous examples of insects’ remarkable sensory abilities and unusual locations for sense organs. Nonetheless, I think they merit a little more attention here. Probably the most remarkable sense organs on insects are their antennae, which can detect touches, movements, smells (chemicals), and even sounds in many insect species. Like us, their limbs and joints can detect their position in space (proprioception), as well as their movements.

Sight

Within insects’ compound eyes, each individual eye lens is immobile, but the brain merges each individual eye’s image to create a unified image. Insects have a wider field of vision than humans, but human vision has higher resolution. Some insects have additional simple light-sensing receptors, ocelli, for detecting light and dark. For instance, wasps and damselflies have a pair of compound eyes, as well as a trio of ocelli on their foreheads.

Figure 04. Even in this cellphone photo, you can see this damselfly’s compound eyes (and maybe its trio of ocelli?).

Insect vision varies across species. Diurnal bees and butterflies have exceptional daytime vision, but cave-dwelling crickets don’t. Most insects can sense light and dark, and most can see polarized light. Many insects can readily detect rapid movements, but not all have acute color vision. Many insects can see infrared wavelengths, as well as the same light wavelengths we can see. Bees and some other insects can sense ultraviolet light wavelengths, as well as green and blue wavelengths, but not red; in contrast, most humans see red, green, and blue wavelengths, but not ultraviolet.

Many insects have specialist requirements for vision. For instance, dragonflies’ sight is specialized for predation — they succeed in more than 95% of their attempts to catch prey — a remarkable statistic! Whirligig beetles, which live at the surface of the water, have two specialized compound eyes. Half of each eye functions differently: The bottom half of each compound eye can see clearly underwater, while the top half of each eye can see clearly in air. Their tiny brains can process this information to form an accurate image of their world.

Chemical Senses: Smells and Tastes

Insects typically detect smells with chemoreceptors on their antennae or their mouthparts. Their chemoreceptors can detect both volatile compounds (carried through the air) and odorants (on surfaces they contact). Insects can detect thousands of different chemicals — yummy food, sexy prospective mates, dangerous predators, good locations for laying eggs, and much more. The antennae of male moths can detect the presence of female moths’ pheromones from more than half a mile away.

Sensory acuity may involve trade-offs, such as great visual acuity requiring a trade-off for superb chemical or tactile acuity. Apparently, most insects with well-developed eyes and visual acuity tend to have simpler, less sensitive chemoreceptors, and vice versa.

Fun fact: Houseflies can detect taste with receptors on their feet, which can detect sugar with 100× more sensitivity than our tongues can do. It’s actually pretty smart to be able to land on a potential food, and taste it, before deciding to stick around long enough to try to eat it. That’s particularly true for flies because they need time to project digestive juices onto the food, wait for it to pre-digest, then suck up the resulting liquid.

Detecting Sounds

For Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies), being able to detect the approaching sound of an echolocating bat can be a matter of life or death. But don’t bother looking for insects’ ears on their heads. That is, unless you look inside the mouths of some moths, who have sound receptors in there.

In addition to being able to hear the ultrasonic clicks of bats (e.g., Hedylidae moth-butterflies), some moths (e.g., hawk moths) also produce their own ultrasonic clicks, which jam the bats’ sonar and warn other moths of the predator’s presence. Some unpalatable moths send warning clicks to bats, alerting them that they’re not tasty, but some palatable moths have evolved to mimic these warnings, as well.

For most insects, their sound receptors are rarely on their heads. Instead, you may find sound receptors on the thorax, the abdomen, the legs, or even the base of the wings. For many insects, their sound receptors are located on thin vibrating membranous tympanal organs (like our eardrums).

Instead of eardrums, some insects have hair-like sensilla for detecting sound vibrations. Sensilla can be found on the antennae of adults, or on the entire bodies of insect larvae. The hairs covering butterfly larvae (i.e., caterpillars!) can detect not only sounds, but also tastes, and even touches. In fact, sensilla can be located almost anywhere on an insect’s exoskeleton and can be adapted to detect sounds, smells, heat, humidity, touch, and other sensations.

Most insects can hear only a narrow range of frequencies — typically the frequency of the sounds of a predator or prey, or the frequencies of the sounds they produce themselves. For instance, mosquitoes can hear up to 2 kHz (kilohertz), about in the middle of the human hearing range of 20 Hz (Hertz) to 20 kHz.

Magnetoreception — Sensing Earth’s Magnetic Field

As mentioned in one of my blogs about Ed Yong’s book — https://bird-brain.org/2025/07/27/sensational-animals-part-3/#11 — bogong moths use Earth’s magnetic field as a guide for their long-distance migrations. Some other insects can detect magnetoreception, too. For example, some ants and bees can use magnetoreception for navigation, both when migrating and when returning to their nests. The Brazilian stingless bee detects magnetic fields using the hair-like sensilla on its antennae.

Figure 05. Using multiple senses (including magnetoreception), some colonial bees show exquisite highly detailed spatial orientation when they leave the colony to gather resources. They’re able to fly several miles to a specific location, within 1/5″, even when it’s surrounded by similar locations. (These bees are located in the Africa Rocks Aviary of the San Diego Zoo, within range of the aviary’s bee-eater species.)

Reproduction and Development (and Metamorphosis)

Most insects are oviparous, reproducing by laying eggs, from which the young will develop and hatch outside the mom’s body. A few insects (e.g., aphids, tsetse flies) are ovoviviparous; in these insects, the eggs fully develop inside the mom; when she lays the eggs, they hatch immediately. A few other species (e.g., the cockroach genus Diploptera) are viviparous; their young gestate inside the mom and are born alive (just as human babies do). Even less common are insects (e.g., parasitoid wasps) that are polyembryonic, in which a single fertilized egg divides into many separate embryos. Within a given year, insects may have one, two, or many broods.

For insects that hatch from eggs (most!), fertilization and at least some development occurs inside the egg. Unlike the eggs of other arthropods (and many other invertebrates and some vertebrates), most insect eggs have three layers surrounding them: the outer chorion (shell), the amnion (a thin membrane containing amniotic fluid), and the serosa, which secretes a chitinous substance that helps keep the egg from drying out.

Among the majority of insects, who start out as eggs, there are two basic ways to metamorphose (develop by changing shape) into adults:

- Incomplete metamorphosis (the process used by about 15% of insects)

- Complete metamorphosis (the process used by about 85% of insects)

Incomplete Metamorphosis

Insects who undergo incomplete metamorphosis (e.g., locusts) hatch from the egg phase to become nymphs, which have pretty much the same shape and appearance as adult insects, but are much smaller. They may also prefer a different habitat and show different behavior from adult insects.

The nymphs start out tiny (egg-sized), with the typical hard, inelastic exoskeleton of all adult insects. As with all arthropods (see previous description of molting), while the nymphs grow, they must develop a new exoskeleton directly beneath their existing exoskeleton. Once the new exoskeleton completely covers the growing nymph, it breaks free of the tight old, constraining exoskeleton. As it continues to grow, it must continue to go through a series of molts until it finally reaches full adult size. Not until it reaches full adult size does it start behaving like an adult — and looking for love.

Incomplete metamorphosis phases (e.g., dragonflies, grasshoppers, cockroaches, true bugs):

- The egg hatches to become

- a nymph, which grows until it reaches

- adult size and then it starts acting like an adult.

The nymph and the adult may differ in that the adult may have wings, which the nymph lacks.

Complete Metamorphosis

In complete metamorphosis (e.g., butterflies, moths, beetles, wasps, flies, mosquitoes), the phases are more complicated:

- The egg hatches to become

- a larva, which eats like mad, to grow enormously,

- then it forms a pupa, during which time it transforms dramatically,

- then it emerges from the pupa as an adult.

Figure 06. (a) This caterpillar started out as an egg, then hatched into this larval form. Once it has eaten enough and grown enough, it will form a pupa, in which it will metamorphose into its adult form — a butterfly. (b) This monarch butterfly isn’t the same species as the caterpillar, but it has the same body plan and life cycle.

You can’t tell by looking at an insect egg whether it will undergo incomplete or complete metamorphosis, but once it hatches, it becomes obvious what’s happening. Larvae come in various shapes and sizes (e.g., caterpillars, grubs, maggots), but the general idea is a squooshy critter with a mouth and an anus, with its main focus on eating and growing.

Once the larvae have eaten enough and grown big enough, they’re ready to create pupae. Moths (nocturnal lepidoptera) and some other insects create a fuzzy silk cocoon, using their own saliva to make a silky thread, wrapped round and round. They attach the cocoon to a leaf or other surface. Other insects, such as butterflies (diurnal lepidoptera) create a chrysalis. To form a chrysalis, the butterfly attaches itself to suspend from a plant part (or other location), then it molts out of its “skin,” forming a liquid outer barrier, which hardens.

From the outside, looking at the pupa, it looks like nothing is happening; the developing insect appears to be at rest. In truth, the insect inside the pupa is undergoing a radical transformation. The tissue of the larva is broken down completely, to create an entirely new adult insect, complete with internal organs, reproductive system, wings, legs, antennae, and so on, depending on the species. Once the transformation is complete, the pupa splits open, and a new adult emerges.

In either kind of transformation, the young and the adult may differ in habitat and diet, but this difference is more pronounced for insects undergoing complete metamorphosis. Their life ambitions differ, too — the goal of larvae is to eat and grow; the goal of adults is to reproduce.

Sex

Not all insects need a sexual partner to reproduce. Some insects are parthenogenetic — the female can produce unfertilized eggs, which hatch and develop, never having been fertilized by a male. Many bees, wasps, and ants reproduce asexually. Aphids even have an alternating system of reproduction, sometimes reproducing sexually (usually in autumn) and sometimes asexually (usually in summer). A benefit of asexual reproduction is that you don’t need males; a drawback is that all your offspring are genetically identical, which means that the chances for adaptation are fewer.

With sexual reproduction, males and females have differing goals. Females prefer to mate with numerous males, to obtain the best variety of genes, ensuring that at least some of her eggs survive to proliferate. In contrast, males want only their own sperm to produce eggs. Males have at least a couple of strategies for increasing their chances to be the only inseminator:

- Take a very, very long time to copulate (e.g., 10 days by a stink-bug species; 79 days by a stick-insect species)

- Scoop out any existing sperm inside the female before inserting their own sperm

- Stick with the female until she lays the eggs (e.g., male blue damselflies)

Fun link: For more information about damselflies (with a photo), visit the San Diego Zoo’s website, “Dragonfly and Damselfly | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants,” https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/dragonfly-and-damselfly

Females have their own strategies, too. Female insects can store the sperm and only later decide which sperm to remove from storage to fertilize her eggs. Also, for many male insects, it’s pretty risky to have sex. Some males die in the process of inseminating the females; often, male mantises are even consumed by their female mates.

Among most colonies of ants, honeybees, and stinging wasps, almost all the individuals are females. The queen is a female, and all the workers are females. The colonies keep a handful of male drones for inseminating the queen. In some species, while the male is inseminating her, his penis is torn apart from his abdomen, so he dies soon after having sex with the queen.

Fun fact: Perhaps not surprisingly, worker bees live only about two weeks, whereas nursery bees who care for the larvae can live for many weeks. Surprisingly, however, if a worker bee is forced to become a nursery bee (for whatever reason), the worker/carer lives as long as the other carer bees.

Among honeybees, the young become males or females based on whether the egg is fertilized (female) or not (male); the queen bee decides whether she’ll fertilize the egg. She also determines whether the egg will grow up to be a worker (the vast majority) or a queen, in which case the larva will receive special nourishment.

Fun fact: Because bees, ants, and aphids are so numerous, and they’re almost all females, at least part of the year, insects tip the balance of the sexes on Earth to be more females than males.

Caring for the Young

Most insects lead solitary lives, in which adulthood is brief, and after they’ve reproduced (mated or mated and laid the eggs), they leave their offspring to fend for themselves. Some do ensure that their young will have adequate food upon hatching. For instance, many dung beetle parents (male and female) will bury balls of dung, on which the mom will lay their eggs. Among wasps and bees that don’t live in hives, many nonetheless provide for their young, creating a nest or burrow, then providing some food in it, then laying the eggs on the food. You could say that many parasitic insects are caring parents because they lay their eggs in or on insects or other animals, so that their larvae can eat the dying (or dead) host.

Fun link: For more information about dung beetles (with photos, including dung beetles and their dung balls), visit the San Diego Zoo’s website, “Dung Beetle | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants,” https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/dung-beetle

Some noted caregivers include earwig moms, who tenderly watch over their eggs, bathing them with an antifungal substance. Then when their nymphs hatch, the moms fetch food to feed to their young. One researcher suggested that maternal care increased survival from 4% to 77%. Burying beetles and treehoppers also provide parental care to their young. Among giant water bugs, it’s the dads who provide care. After a pair mates, the mom lays her eggs neatly on the dad’s back, and from then on, he floats with the eggs atop the water, ensuring that the eggs don’t drown and don’t dry out.

Among viviparous insects who give birth to live nymphs, the moms must provide nutrients to the eggs while they develop inside her. Insect moms don’t have a uterus with an umbilical cord to feed their young. In a species of cockroach (Diploptera punctata), mom’s abdomen has special glands, which secrete a liquid milky protein that feeds her developing eggs. Like human milk, the cockroach “milk” contains a perfect blend of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats for her developing eggs.

Deerfly moms don’t give birth to live nymphs, but they, too, feed their eggs through liquid secreted from specialized glands. Instead of emerging as nymphs, her well-fed eggs emerge as pupae, which fall to the ground and then hatch months later.

Colonies of social insects (many bees, ants, wasps) are devoted to providing care for their young. The queen’s job is to continually produce eggs, and the full-time job of many members of the colony is to feed and care for the youngsters. The workers are dedicated to leaving the colony, finding nectar and pollen, and returning to the colony to feed the others of the colony. Male drones give their lives to inseminate the queen.

Success of Insects

By almost any measure, insects are an astonishingly successful group of animals. As an indication of their success, there are more than a million different species of insects — more than any other animal on Earth. (Some entomologists say that the number of species may even be five times that many; they just haven’t yet been identified.) In fact, more than half of all animal species are insects. Estimates guess that there are 1–10 quintillion insects on Earth, or more than 200 million insects for every 1 human.

Figure 07. DGPH Studio designed Amazing Insects around the World to invite young readers to observe the natural world and the amazing insects in it. At the back of the book is additional information about insects, written at a level young readers can grasp.

In addition, insects must be doing something right because they started evolving on Earth almost 480 million years ago — before dinosaurs existed. Insects have survived five mass extinctions.

A few characteristics contribute to their fantastic success:

- They’re astonishingly fecund; on the other hand, they have to be prolific because most newly hatched insects die of starvation, predation, or other means before they ever reach adulthood. Insect eggs, larvae, and adults are the favorite food item of many animals — including many insects!

- At different stages in their life cycles, insects have different food preferences, so youngsters aren’t competing with adults for particular kinds of food. Caterpillars prefer leaves, but butterflies prefer pollen and nectar.

- Most insects have wings, which allow them to move from unsuitable places to more comfortable locations with more abundant food sources. Being able to fly also means more easily gaining access to food in three dimensions, not just on the ground.

- Insects are highly adaptable to almost every habitat on Earth — land and sea, desert and poles, on every continent. (Antarctica hosts a flightless midge that can’t tolerate temperatures above 50º F. Snow scorpionflies enjoy the Arctic and high altitudes.) You’ll find more species in the tropics than in cooler locations, even temperate ones, but you’ll be hard pressed to find an insect-less locale. Though few insect species (maybe 100 or so) truly love marine environments, about 30,000–40,000 species live in freshwater, and some live on the open ocean.

Insect Resourcefulness

We humans are a very clever species, but we’re not the first species to farm food crops, raise livestock, or make and use nets. At least 50 million years ago, ants and termites were farming fungus crops in social communities.

For instance, farming communities of leaf-cutter ants have assigned roles for different members of their community. Some ants go out of the mound to find leaves and cut off portable bits of leaf to carry home. Other ants chew up and distribute the leaves to the next group of ants. Those ants lick the leaves, to transfer fungi to the leaves and plant the leaves in their leaf-fungus garden. A different group of ants is responsible for tending the garden, removing unwanted fungi or microbes (“weeding”). At last, some of the ants harvest the nutritious fungi and distribute it to all the workers, as well as — importantly — the ant larvae. Please note. Leaf-cutter ants do not actually eat leaves.

Fun link: For more information about ants (with a photo of leaf-cutter ants carrying part of a leaf), visit the San Diego Zoo’s website, “Ant | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants,” https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/ant

Termites (cousins of cockroaches) do something similar with wood pulp. Some of the termites harvest the wood pulp — sticks, grass, straw — and other termites mix the pulp with their saliva. The termites and their fungi have a different living arrangement than the ants. The fungi break down the pulpy plant material and convert it into food the termites can easily digest. In the process, the fungi can also be fed, so everybody wins. To ensure that the fungi have an agreeable temperature and humidity, the termites construct their mounds to have a passive air-conditioning system, which they adjust, as needed.

A species of bark beetles goes one step beyond simply cohabiting with its fungal partner. It carries this fungus in mycangia, special body cavities designed for transporting their symbiotic partner from tree to tree. As with the termites’ fungi, the beetles’ fungi convert tough tree cellulose into material the beetles can eat and digest. When adult beetles are ready to start a family, they find a suitable dead or dying tree, dig out some nurseries, line the nurseries with fungi, and leave their eggs to hatch into larvae, with a ready-made food supply.

Fun fact: Social wasps don’t need fungal help to digest plant cellulose; they gather weathered wood, soften it by chewing it, and mix it with saliva to make paper from which they construct their nests (which have hexagonal cells like those of bees).

In addition to farming, insects have been keeping livestock for at least 100 million years. In particular, ants have been keeping aphids (fellow insects) so that they can eat what the aphids excrete. Specifically, aphids eat almost entirely tree sap, which has very little nutrition, so the aphids have to consume a whole lot to extract the nutrients they need. And when you eat a lot, you poop a lot. Because tree sap is pretty sweet, what comes out the other end — called honeydew — is quite sweet, too.

Which is where the ants come in. The ants are obsessed with eating the aphids’ sweet honeydew, and they vigorously defend “their” aphids from any predators. According to Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson, Extraordinary Insects: The Fabulous, Indispensable Creatures Who Run Our World, “An ant colony can easily harvest 22 to 33 pounds of sugar from aphids over a summer; some estimates go as high as 220 pounds of sugar per anthill per year” (p. 79). A pretty sweet deal. The aphids have no use for the honeydew, and the ants love it. The tree doesn’t love having the aphids run amok eating its sap, with no predators to stop them or even slow them down, but the ants pay little for their constant supply of food. Unfortunately, the ants can go overboard in “protecting” their aphids, preventing them from leaving to go to other plants, sometimes even biting the aphids’ wings to keep them flightless. In environments where bears eat the ants, ladybugs can freely eat the aphids, and the trees thrive.

Fun link: For more information about ladybugs (with photos, including ladybug larva), visit the San Diego Zoo’s website, “Ladybug | San Diego Zoo Animals & Plants,” https://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/ladybug

Some insects also resourcefully use silken threads. For instance, caddis fly larvae spin silken nets for trapping small aquatic creatures in streams. The larvae of fungus gnats (related to mosquitoes) spin nets for trapping small insects or for gathering fungal spores. In at least one species of dance flies, when the male catches another fly (ideally, a competing male), he wraps up his catch using silky thread he produces from his forelegs. Grace lacewings also use silky threads to keep their eggs safe from predators. In all, more than 20 insect species have been able to spin silk, to use it for various purposes.

Importance of Insects

“E. O. Wilson wrote, ‘The truth is that we need invertebrates but they don’t need us. If human beings were to disappear tomorrow, the world would go on with little change. . . . But if invertebrates were to disappear, I doubt that the human species could live more than a few months” (p. 199, Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson, Extraordinary Insects: The Fabulous, Indispensable Creatures Who Run Our World).

Figure 08(a–c). Insects are resilient. This butterfly was floating atop the pool, but after being lifted out, it came to life! In a little more than an hour, it seemed to recover and was to be able to flutter about. Update: It was still fluttering about the next day.

Pests

Insects aren’t entirely beneficial to humans, other animals, or natural habitats. Lice, bedbugs, fleas, and other insect parasites attack people, livestock, and other animals. Mosquitoes and other insects spread numerous diseases to humans and to other animals. Annoying, blood-sucking horse flies spread diseases to zebras and other wild animals; luckily, the zebra’s stripes appear to deter these harmful insects, which have difficulty landing on striped surfaces, especially if the zebra is moving.

Insects can cost us indirectly, as well. Locusts and thrips devour agricultural crops; wheat weevils destroy stored agricultural produce; these pests lead many farmers to use extremely polluting methods, such as deadly chemicals, to try to defend against hungry insects. Termites damage our homes and other wooden structures; aphids and bark beetles decimate our forests; wasps invade our attics and eaves. Fortunately, many plants develop their own chemical defenses against invading insects, boosting their production of tannins, as well as producing peppermint and mustard to deter herbivorous insects.

Oregano plants produce carvacrol, a defensive chemical insecticide, which deters most insect pests. However, Myrmica ants can resist the insecticide, continuing to attack the plant. But that’s not the end of the story. Carvacrol also alerts large blue butterflies, which flutter to the oregano and lay their eggs on its leaves. When the larvae hatch, they fall to the ground, smelling exactly like Myrmica ant larvae. The ants tenderly carry the larvae back to their nests and feed them. In turn, the butterfly larvae not only scarf up the ants’ regurgitated plant food, but also all the ant larvae in the nest, pretty much eliminating the colony of hungry ants. Well played, oregano.

Helpers

Though many insects can indeed be pests, most provide vital services to our ecosystems and even to us humans specifically. Following are a few of the ways in which they help us: as predators who attack harmful insects and other pests, as prey who feed myriad birds and other animals, as decomposers who remove or transform dead organisms and excreta, as pollinators who ensure the availability of myriad foods we love, as seed dispersers, as soil protectors and guardians, as symbionts to some animals and plants, as food for humans and for the animals we eat, as producers of countless products (e.g., beeswax, honey, silk, gall ink, cochineal red dye, shellac, pharmaceuticals), and as providers of services (pets, wound care, research, inspiration for biomimicry, search and rescue).

Insect Predators and Prey

Many insects can be helpful as biological controls against insect pests; insectivorous insect predators can be launched against herbivorous insect prey. In natural forests, predatory insects and parasitic insects can limit the numbers of spruce bark beetles and other pests by eating them. Aphids prey on various crops and other plants, but ladybugs feed on aphids; some farmers are buying flocks of ladybugs to protect their crops. Wasps, other stinging insects, and other insect predators and parasites can limit the populations of unwanted small vertebrates and arthropods, including some insect pests.

Figure 09. Most birds are insectivores, including these White-Breasted Woodswallows and this Metallic Starling (at the San Diego Zoo’s Owens Aviary).

As prey, insects provide food for many animals, including some humans. Many mosquitoes and other insects provide essential food for birds, fish, bats, and other animals, benefitting their entire ecosystem. Most birds (>60%) thrive based on an insectivorous diet, as do most bats.

Decomposers

Perhaps the most important way in which insects provide a vital service to humans and to Earth’s entire ecosystem is as its chief decomposers. De-compos-ing literally means to break apart organic matter, so that it can be used again, to compose anew.

Carcass Removal

All animals eventually die, and whenever any animal dies, it leaves a plentitude of nutrients — proteins, carbohydrates, fats, as well as micronutrients such as calcium and other minerals. Large scavengers such as vultures and hyenas do a splendid job of eating big hunks of flesh, but they’re not exactly neat eaters, and much still remains after they finish scavenging. Some smaller scavengers help, but nothing polishes off the last bits of a carcass as well as a swarm of insects.

A particularly effective strategy for recycling dead carcasses is to lay your eggs directly on or in the carcass, so your larvae are hatched into a ready supply of food. Some insects go to a bit more trouble, too. For instance, burying beetles will dig a tunnel from beneath the carcass to a dug-out nursery away from the carcass. Then the parents can easily snip off bits of the dead animal, chew up and carry the bits over to their larvae, regurgitate the masticated food, and then scurry back for more. The larvae can gain nourishment from the food only if it’s been pre-digested by their parents.

Dung

As a wise children’s book title says, Everyone Poops (Tarō Gomi). We would not want to imagine our world if we didn’t have specialized insects who relished decomposing poop efficiently. Many species of beetles (e.g., “dung beetles”) and flies (e.g., “dung flies”) dedicate themselves to decomposing poop. Both types of insects have exquisite senses of smell, along with rapid reflexes for finding and quickly disposing of poop. I like to think of them as “dungivorous” — they’re actually called coprophagous, but doesn’t dungivorous sound better?

As just one example, researchers took 3 pounds of elephant dung and a stopwatch to observe what would happen. Within about 2 hours, all of it was consumed by 16,000 dung beetles. Poop contains not only rich nutrients to be recycled, but also myriad disease vectors — parasites, bacteria, and other pathogens — which can be spread if not recycled by insects. The coprophagous insects not only use the dung to feed themselves and their larvae, but also recycle the nutrients into forms that other organisms can use. These services are courtesy of insects who ask for little in return.

Unfortunately, we not only give them nothing in return, but we also make their lives harder: We use pesticides near livestock, toxic drugs to treat livestock for parasitic diseases, and insect-unfriendly practices with our livestock. (Regarding the toxic drugs, we could help out by using the drugs only when needed, and then using injectable drugs rather than orally administered drugs that end up in the dung.) We also eliminate and encroach on their natural habitats.

Plant Debris

Herbivores eat about 10% of the plant debris that is left on the ground; all the rest must be recycled by other means. These plants also contain massive amounts of nutrients, which aren’t available to other organisms unless they’re made available. With plant matter, insects get help from fungi to decompose it. Each species of insect and fungus has its role in the decomposition ecosystem, which enriches the soil and makes vital nitrogen, carbon, and other resources available for new growth.

Figure 10. Insects such as this beetle play vital roles in decomposing dead matter and waste, turning it into valuable, usable nutrients.

Dead trees require a different team of decomposers, still including insects and fungi. Literally thousands of different species of insects may live in dead wood, in the same area where you might find a few hundred bird species and maybe several dozen mammal species. Each insect has its own specialty — different species of trees, different sizes and ages of trees, different ecosystems surrounding the trees, different stages of decomposition, and so on. Even different parts of trees — branches versus trunk, canopy versus base — appeal to different insects.

For instance, newly dead trees may still be filled with the trees’ chemical defenses to ward off herbivores, and some insects are better prepared to deal with those chemicals than others. On the other hand, those trees will still contain sap, so sap-sucking beetles will readily make a home there. A mama beetle eagerly seeks out newly dead trees for her family. When she stumbles across a possible home, she tastes and smells it, using her antennae and her feet. If it smells and tastes good enough, she’ll lay her eggs there, assured that her emerging larvae will gobble up the scrumptious sappy wood.

As the tree dries out, assorted species of fungi and bacteria convert the truly tough material — such as lignin and cellulose — into forms that insects can decompose. When the sappy bits ferment, other insects step up to aid the decomposition process. Mosses and lichens join the fungi, bacteria, and insects, too. According to Anne Sverdrup-Thygeson (p. 113, Extraordinary Insects: The Fabulous, Indispensable Creatures Who Run Our World), pretty soon, “there are more living cells in the dead tree than there were when it was alive.” All of this decomposing takes place in a natural forest, which is crowded with abundant and diverse living and dead trees, so that a variety of decomposers can feast. A managed monoculture forest with identical species, spaced apart, and with few or no dead trees is inhospitable to most decomposers. (Monocultures include only one species of trees, plants, or other organisms.)

Urban Decomposers

That’s not to say that decomposers can’t find plenty to consume even in urban environments. About 40 species of ants make New York City their home — perhaps about 2,000 ants per person living in Manhattan. Of course, many insects can be found in parks, but they also happily find homes even on busy streets. There’s even a “pavement ant” who eats about three times as much as any other urban ant species. Many insects find pedestrian islands more suitable because they tend to be warmer than shady parks, and some of these ectothermic (cold-blooded) critters like basking in the sun.

Decomposition of Plastics

Right now, less than 10% of the plastic we discard is recycled. So far, we haven’t made much progress in avoiding the use of plastics or in finding ways to recycle plastics. Insects may offer us some hope, though, at least in regard to polystyrene (aka “isopore”), which is not biodegradable.

Polystyrene can be made into solids (e.g., yogurt cups) or foams (e.g., cups and other containers for holding hot beverages and takeout food). Literally billions of polystyrene cups are tossed away every year. Initial experiments showed that the larvae of darkling beetle species (Tenebrio molitor, Tenebrio obscurus, Zophobas atratus) will readily consume polystyrene foam. These larvae had the same survival rates as the same species of larvae fed a normal diet. Both groups of larvae pupated, and both became normal adults, expiring CO2 and excreting poop that could be used as planting soil. Actually, the larvae first chew up the polystyrene, exposing the pieces to air, then the larvae’s bacterial gut enzymes break down the polystyrene, converting it into nutrients the larvae could use.

A different class of insects may help with a different kind of plastic: polyethylene, the most common type of plastic. It’s used to make flimsy shopping bags, as well as some kinds of plastic containers (jars, bottles, etc.). The larvae of the greater wax moth (in symbiotic relationship with its gut bacteria) will eat polyethylene (presumably the flimsy stuff), converting it into ethylene glycol, antifreeze.

Researchers may be able to find additional hungry insects to address our abundant and ever-increasing plastics problem.

Pollinators

Most plants need to be pollinated in order to reproduce. During pollination, pollen grains (fine powder) are transferred from one flower to fertilize another flower. Specifically, pollen from one flower’s male anther is transferred to a different flower’s female ovule. The fertilized egg then develops into a seed (perhaps surrounded by a fruit).

Figure 11. This malachite butterfly is among the many pollinators who make possible the abundant plant life we enjoy (seen at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park’s Butterfly Jungle, 2019).

Of the hundreds of thousands of animal species that pollinate flowering plants, all but 1,500 species are insects. Flowers entice these myriad insects to transport their pollen by offering the insects energy-rich nectar, as well as protein-rich pollen. Insects had existed long before flowers evolved, but it’s thought that flowers co-evolved with insects from that time forward. An example of this co-evolution is the corpse flower, which releases the putrid stench of decaying flesh when it’s ready for pollination. The wretched odor attracts blowflies to pollinate it. Another flower, the fly orchid, disperses smells that mimic that of female digger wasps, thereby attracting the males of this species.

Quite a few of our grain crops are pollinated by wind — rice, corn, some other grains. At least one third of the foods we eat, however, rely on insects for pollination. Fruits, berries, and nuts feature prominently, but other foods, too. Here are just a few: almond (e.g., marzipan), apple, apricot, artichoke, asparagus, blackberry, broccoli, brussel sprouts, buckwheat, cabbage, canola (rapeseed), cantaloupe, casaba, cashew, cauliflower, celeriac, celery, chervil, chestnut, chicory, chive, chocolate (cacao), clove, coconut, coffee, coriander, cottonseed, cucumber, currant, dill, eggplant, endive, fennel, flaxseed, gooseberry, grape, grapefruit, guava, honeydew, kale, leek, lima bean, mango, mustard, nectarine, olive, onion, orange, papaya, parsley, parsnip, passionfruit, peach, peanut, pear, pepper, persimmon, pimento, plum, pomegranate, pumpkin, quince, radish, rutabaga, safflower, soybean, squash, strawberry, sunflower, tangelo, tangerine, tea (various), turnip. (Most of these foods were listed in materials from the San Diego Zoo Interpretive Training “Arthropods” course.) In addition, many of the animals that we eat are fed alfalfa and clover — both of which are pollinated by bees.

Worldwide, wild insects boost the crop yields and the quality of foods that we and our livestock eat, even for crops that don’t rely on insect pollination. Some estimates suggest that pollinating insects contribute more than half a trillion dollars of value to the world’s food. In the United States alone, in 2021, the value of insects’ pollination of food crops and fruit trees was about $34 billion.

In addition, more than 80% of wild plants are pollinated by insects. Certainly the most efficient pollinating insects are honeybees, bumblebees, and wild bees. Nonetheless, many other insects provide important pollination services, such as butterflies, flies, beetles, wasps, and even ants. Though they may not pollinate as efficiently on each visit, given their abundance, their accumulated visits are still important to plants. These non-bee pollinators boost the productivity of crops even when they’re visited by bees, too. In addition to being added crop-pollination “insurance,” some of these insects have specialized pollination abilities. Some insects prefer cooler temperatures, whereas others relish the midday heat. Some may have trouble adapting to natural fluctuations, climate changes, and human-made modifications, whereas others may thrive under altered conditions.

Chocolate, Cacao Trees, and the Chocolate Midge

To produce cacao seeds, pollen from one tree’s flowers must be transferred to a second tree’s flowers. To make matters more difficult, cacao flowers are intricately constructed, making it challenging for most insects to get inside it. Luckily, chocolate midges are the size of a poppy seed, so they’re tiny enough to crawl inside the cacao flower. But the midge’s tiny size also means it can’t carry much pollen at any one time. To make matters worse, these midges don’t fly well, and the cacao flowers don’t last longer than 1–2 days. But this tiny powerhouse and its colleagues rise to the challenge. Chocolate midge champions single-handedly ensure that all of us can enjoy eating chocolate.

Figure 12. Chocolate . . . a delightful aroma, a scrumptious taste, . . . one of life’s great pleasures.

In a natural rain-forest setting, the chocolate midge gets plenty of shade and humidity. Its larvae like to hatch in the thick leaf litter of a rain forest, where there’s plenty to eat. Unfortunately, cacao plantations provide neither shade nor humidity nor leaf litter. On the plantation, only 0.3% of cacao flowers mature into fruit. On a plantation, during the 25-year lifetime of a cacao tree, it may produce only enough cacao beans to yield about 11 pounds of chocolate — about as much chocolate as most Americans consume in a year.

Almonds

California farmers produce 80% of the world’s almonds, using about 450,000 acres for their carefully planned orchards. In these orchards, trees must be spaced in rows, far enough apart for a mechanical harvester to drive down each row, shaking the trees to harvest the almonds. Wild bees and other native insect pollinators aren’t attracted to these orchards because there are no plants between the trees. As a result, each year (mostly in spring), farmers must pay to transport more than 1 million beehives from other locations to pollinate the almond trees in these unnatural orchards.

Figure 13. I deeply appreciate the insects who pollinate coffee trees, providing me with coffee beans for aromatic ambrosia each morning.

Coffee

Coffee beans don’t need insect pollinators, as the plants can pollinate themselves. Nonetheless, the trees yield many more beans when they’re cross-pollinated by insects. Many species of bees — honeybees, other social bees, and solitary bees — pollinate coffee trees, boosting the coffee yield by up to 50%. For these bees to thrive, however, they need access to woodlands. Dead or old trees have hollows that offer ideal homes for some bee species; small patches of shaded bare earth well suits some other species. Another bonus to having woodlands surrounding the coffee plantation: Shade-grown coffee beans are more flavorful.

Tastier Fruits

Some observers note that insect-pollinated strawberries are tastier and keep better than wind- or self-pollinated strawberries. The same has been said of insect-pollinated tomatoes. Other fruits that seem to benefit from insect pollination: apples, blueberries, melons, and cucumbers. Also, canola seeds (rapeseed) have a higher oil content when insects pollinate them.

Figure 14(a–c). One of life’s greatest delights is to enjoy tasty fruits such as cucumbers, plums, and blackberries. (Yup! Cucumbers — like tomatoes — are fruits: seeds + pulp + skin = fruit.)

Seed Dispersal

In addition to insects that disperse pollen from one flower to another, many insects distribute mature seeds. More than 11,000 different species of plants use insects to carry their seeds a distance from the parent plants. As a thank-you, plants often attach a food packet (e.g., fruit or nut) for the insects’ transportation service.

Soil Protection and Creation

Precious soil is often eroded by water or wind, especially when humans remove natural vegetation from the soil. Myriad invertebrates (earthworms, mites, roundworms, insects) help to dig, churn, and aerate the soil, to keep it from eroding and to keep it ready for use by plants. Fungi, lichen, and bacteria help, as well. They create new soil, too, by decomposing dead matter and excreta. Insects also structure the soil in ways that allows it to absorb more water and more nitrogen.

Insects’ work on soils makes a noticeable difference. For instance, in some arid areas of Australia, fields where insects flourished yielded 36% greater harvests than fields where insecticides were used. Some suggest that their role in forming and protecting soil may be worth many times as much as their role in pollination.

Symbiotic Relationships

Three-toed sloths take a big risk of predation any time they descend from the trees to the ground. Nonetheless, each week, they climb down to the ground — literally risking life and limb — to poop. Why don’t they just drop their poop from a safe treetop branch? These sloths carry an ecosystem in their fur. Living in the sloth’s fur are sloth moths (2 genera, 5 species). For sloth moth larvae to develop, sloth moth eggs must be laid on top of sloth poop. So each week, the sloth obligingly descends to poop, so its moths can lay their eggs on its poop.

Why are sloth moths so important to the sloth? Because after sloth moths become adults, they spend their entire lives in the sloth’s pelt — eating, pooping, dying, and decomposing there. That makes the sloth’s coat abundantly rich with nutrients to be consumed by a particular kind of alga, which grows nowhere else on Earth. The algae eat the nutrients left by the sloth moths, and the sloth eats the algae, licking the algae off its fur. The sloth-moth-loving algae offer the sloth nutrients otherwise unavailable from its tree-leaf diet — and it provides a nice green hue to camouflage the sloth from potential predators. So . . . the sloths help the moths, who help the algae, who help the sloths, who . . .

Another symbiotic relationship between mammals and insects is even more unsavory. Some mammals — such as kangaroos and apes — have beetles living in their fur near their anus — I’ll let you imagine the rest.

Foods

Insects not only pollinate the plants we eat and provide food to insectivorous animals, but also feed humans directly as food. Grasshoppers can convert fodder to protein about 12 times as efficiently as cattle; they also consume just a fraction of the water and yield minimal methane or other polluting gases. They also reproduce prolifically, taking up very little space. The little food they eat would otherwise be discarded as waste, so they help solve an additional problem simply by existing.

Figure 15. In 2024, I made a batch of cookies using cricket flour. I confess that I won’t be doing so again any time soon. Nonetheless, I applaud its consumption. Cricket flour has about twice as much iron as spinach and more calcium than milk. In general, most insects have about as much protein as beef, plenty of minerals, and very little fat.

In 80% of the world’s nations (especially Asia, Africa, South America), people consume insects (e.g., locusts, termites, cicadas) as food (i.e., 25%–33% of the world’s people). The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization has observed that globally, in the face of increasing food shortages, humans may need to eat insects as part of our diets. Some military forces recommend consuming insects as a survival food for troops during adverse times.

There are some challenges to widespread consumption of insects, however. First of all, widespread consumer acceptance isn’t guaranteed. Also, we aren’t yet ready to produce large enough quantities of sanitary (no parasites or other pathogens), safe, edible insects to make them affordable and widely available. Climate-controlled storage and transportation may be difficult, too.

Perhaps an easier way to incorporate insects into our diet is to feed them to the animals we do eat. We could feed the insects on our food waste then feed the insects to our livestock. In fact, insects already feed many of the animals we like to eat, such as freshwater fish (trout, perch) and many game birds. Housefly larvae (maggots) have been used to feed domestic animals such as chickens and pigs.

Useful Products Provided by Insects

Insects provide us with myriad useful substances and products, such as honey, beeswax, silk, ink, dye, shellac and lacquer, and even pharmaceuticals. The beetle larvae that consume polystyrene foam are also high in proteins and fats, so they’re often fed to pet reptiles, amphibians, fish, and birds. In addition, their high fat content has led some people to make various fatty substances (cooking oil, “butter,” and fatty alcohols) from them. The larvae of black soldier flies have provided protein and fats for use in cosmetics, as well as for pet food.

Figure 16. Corvids (such as this American Crow) are known for being willing to eat almost anything, but these busy bees aren’t on the menu. If there were a stingless way to retrieve their honey, however, that’s another story.

Bees, Wax, and Honey

Honey has been used in cosmetics, too. The wife of Nero, Poppaea, used a facial mask made by combining honey and asses’ milk (feel free to insert a joke here). If you need some lip balm, you can make your own by mixing honey with vegetable oil. Honey also has antibacterial properties and has been used to treat wounds since at least the time of Alexander the Great.

Humans have been domesticating honeybees (Apis mellifera) for thousands of years. North African pottery vessels from 9,000 years ago show that they were used for keeping bees. Elsewhere, about the same time, yeast (a fungus!) was added to honey-water and allowed to ferment to create mead, the world’s oldest fermented beverage.

Currently, more than 83 billion honeybees provide humans with honey. In 2023, almost 63,000 metric tons of honey were produced in the United States, and almost 1.9 million metric tons were produced worldwide (1 metric ton equals about 2,200 pounds).

Each honeybee extracts nectar from flowers, carrying it in an internal honey crop (aka honey sac), a specialized pouch between its esophagus and its stomach. That prevents the nectar from going through the bee’s digestive system or mixing with other food eaten by the bee. In the honey sac, enzymes start mixing with the nectar before the bee returns to the hive. At the hive, the returning bee regurgitates the contents of the honey sac into the mouths of hive bees, who store it in their own honey sacs and carry it deeper into the hive, where it is transported further, until a hive bee stores the regurgitated and processed nectar — now honey — in wax-lined cells, which are later covered with beeswax.

Fun facts: Honeybees have special glands in their abdomens, which can make beeswax; their beeswax makes superlative housing and storage for their precious larvae, as well as for their honey. Humans have found numerous uses for beeswax, such as for long-lasting candles and for various cosmetics (e.g., creams, lotions, lip balm, mustache wax).

Silkworms and Silk

Charming stories about the discovery of silk in ancient China involve a young girl, hot tea, and a silkworm’s cocoon. However it was discovered, the ancient Chinese found that the larvae of the Bombyx mori moth produce exquisite silk thread. During that time, the only persons to wear silk were the emperor and those whom the emperor chose. China’s production of silk spurred international trade relations along the “Silk Road” from about 200 b.c.e. until about c.e. 1450. Even today, China produces more silk than any other nation. More than 200,000 metric tons of silk are produced yearly, perhaps requiring 100 billion silk moths or more to do so.

The silk larvae produce their silk cocoons just as other insect larvae do, but these cocoons are harvested soon after they’re made. After the cocoons are harvested, they are dumped into boiling water, killing the crafty hard-working larvae and dissolving the cocoon, freeing the fine silken thread. The thread has astonishing strength and resilience, and the resulting light, elegant fabric feels cool and silky against the skin. In addition to its uses for fabrics, its strength allows it to be used for surgical thread and even for bicycle tires. Though silk thread is now made by some other moth species, none are considered as exquisite as the larvae of the Bombyx mori moth.

Gall Wasps and Gall Ink

My blog https://bird-brain.org/2025/02/05/medieval-manuscripts/#gall-ink discussed how scribes made iron-gall ink for writing manuscripts, starting by the 1100s and continuing for long afterward. In fact, iron-gall ink was used for writing Shakespeare’s plays, Beethoven’s symphonies, Linneas’s flower sketches, Galileo’s drawings of sun & moon, and the U.S. Declaration of Independence. It continued to be commonly used in the 1800s, and even today, it is used in works of art or craft.

Though oak galls are most commonly used for inks, it’s also possible to make ink from galls formed on other trees. The walls of the oak gall are stiffened by tannic acid, which plants naturally use as a chemical defense to deter herbivores. (Tannic acid is used for tanning leather and hides and naturally occurs in red wines.) Oak-gall ink was a huge improvement over the carbonous ink used previously, which was water soluble and easily washed or rubbed away.

Figure 17. This is not an oak-gall wasp, but is it a wasp? I would welcome your help in identifying it. In any case, it had landed in the pool, too. (I used a leaf, not my bare hand, to retrieve it.) Pretty soon, this Hymenoptera insect (wasp? bee?) had dried enough to take flight.

Cochineal Insects and Red Dye

The Aztecs and Mayans indigenous to Mexico and Central America discovered how to make various red dyes from female cochineal scale insects (Dactylopius coccus). First, they plucked the scale insects from cactus (nopal, aka prickly pear), then they killed the insects. The color of the dye differed, depending on whether the insects were boiled, steamed, baked in the sun, or baked in an oven. Once they were dried to about 30% of their original weight, they could be stored almost indefinitely.

To make the dye, the dyers would need to use about 70,000 insects for about 1 pound (0.45 kg) of cochineal dye. There are two basic ways to prepare the dye: (1) Make a cochineal extract, using the raw dried and powdered bodies of the insects. (2) Make carmine, a purer coloring made by boiling the pulverized insect bodies in ammonia or in a solution of sodium carbonate; the result is filtered, then alum is added to preserve the color. The indigenous dyers even bred these insects for the intensity of their colors.

After the Spaniards invaded and colonized these areas, they learned about the cochineal insect dyes and began to produce the dyes widely, exporting them to Europe. Europeans coveted the vivid dye for its intensity and for its resistance to sun bleaching. Rembrandt used cochineal reds in his paintings, and the British “red coats” were dyed with cochineal. Peru is now the main exporter of cochineal dyes, which are used more widely in foods, beverages, and cosmetics than in fabrics.

Lac Bugs and Shellac

Lac bugs are “true bugs” — members of the Hemiptera family, just one of many insect families. Several species of lac bugs (native to Southeast Asia) produce a resinlike substance that can be used to make wooden surfaces shiny and waterproof. The lac bug nymphs wrap their mouths around part of a branch and start sucking out sap. As the sap moves through the bug’s digestive system, it oozes out the other end as liquid shellac. When the liquid is exposed to air, it forms a shiny orange-ish roof, which covers the entire colony of bugs and the whole branch they’re sitting on. The nymphs molt a few times during this process and then emerge as adults. The adults mate, lay eggs, and die, then their eggs hatch into nymphs, break through the resin roof, and head out to find their own new sappy branch.

Shellac farmers scrape the resinous “roofs” from the branches, then they crush the scrapings and remove the fragments of insects and molted exoskeletons. They can then either sell it as flakes or dissolve it in alcohol to sell as shellac. Probably the most productive lac bug is the Kerria lacca. It takes about 100,000 lac bugs to produce a kilogram (2.2 pounds) of shellac.

Lac bugs and shellac also have an ancient heritage, having been mentioned in Hindu documents circa 1200 b.c.e., and described by Pliny the Elder in writings from c.e. 77. Nonetheless, it wasn’t widely used in Europe until the late 1300s, when it was used first as a dye and then as a varnish. For about 50 years (1890s–1940s), 78-rpm phonograph records were made using shellac and other ingredients; the records were brittle and lacked good sound quality. Shellac was also used for military purposes, such as for sealing and waterproofing ammunition, detonators, and so on.

Perhaps surprisingly, today, shellac is used on foods, adding gloss to jelly beans, lozenges, and other sweets, as well as to shine up harvested apples, citrus fruits, pears, pineapples, and other fruits — and even eggs! It can be used for pills, not just making them shiny, but also slowing their action because the shellac keeps them from dissolving until they’re past the stomach and inside the gut. Shellac is also used in hair spray and nail varnish, as well as a binder for mascara. It has been used to restore dinosaur bones and is used for varnish, paint, glazes, dyes (jewelry and textiles), sealants, and electrical insulation.

Ants and Pharmaceuticals

Antibiotics and other antimicrobial drugs are no longer as effective as they once were. According to the World Health Organization, bacterial resistance to antibiotics was directly responsible for killing 1.27 million people worldwide in 2019, and it contributed to the deaths of 4.95 million people. We need other solutions to this increasing problem.

What about studying a population that lives in close quarters and is subject to bacterial and fungal infections? Ant colonies definitely need good defenses to fight infections. In particular, fungi-farming leaf-cutter ants have to take steps to ward off unwanted parasitic fungi that try to invade the ants’ fungal gardens. These ants have developed a symbiotic relationship with bacteria, who live in special pouches on the ants’ bodies. These bacteria produce antifungal substances, which can kill off invaders. The ants smear these substances all over themselves and their colony mates (all females), using their forelegs. These ants and bacteria have been collaborating for millions of years. Researchers are investigating whether they can learn from these ants to fight microbe-resistant infections.

Useful Services

Insects also provide valuable services to humans, such as baiting fish, analyzing forensic information, keeping us company as pets, finding people in collapsed buildings, treating wounds, working as research subjects, and inspiring biomimicry. Fishers have long used adult insects, such as crickets, and insect larvae of various kinds, to bait their hooks for catching fish. In cases of suspicious deaths, forensic entomology can reveal time and location of death, as well as (sometimes) toxins that caused death, mostly for humans, but also for other animals.

Pets

Many species of insects have been and are being sold and kept as pets; they’re inexpensive, require little maintenance, and can be easy yet engaging and companionable pets. Caged crickets have been companions in China and Japan for thousands of years. In Korea, it was shown that when elderly adults were given cages containing a few crickets, their mental health improved. Less appealingly, insects (e.g., crickets, beetles) have been bred and spurred to fight, to entertain adults or children. On a more widespread basis, fireflies often attract tourists in parks and fields.

Search and Rescue

After avalanches and many other dangerous situations, dogs make excellent search-and-rescue animals. Unfortunately, in a collapsed, severely polluted, or otherwise dangerous building, dogs either cannot enter the building or should not do so. In such situations, you need a tiny, hardy animal to conduct the search. It turns out that cockroaches make terrific search-and-rescue animals in these situations. With micro-sized technology, it’s possible to make a backpack with a microchip, a transmitter, a receiver — and maybe a microphone — to fit a cockroach. In addition, microcontrol units attached to its cerci (pair of rear appendages) and to its antennae can receive electrical impulses that stimulate the cockroach to move forward or to one side or the other.

If numerous cockroaches are similarly equipped, they can map out an entire building. If a microphone is attached, it can detect any noises made by a person or by the building, and the cockroach can be guided to the source of the sound. Map the location, and it’s possible to know where to find someone.

Wound Care

In the 1200s, the emperor Genghis Khan always made sure to bring a wagonload of maggots when he went into battle. When soldiers were wounded, maggots were placed on the wounds, so they’d heal more quickly, and the soldiers could be sent back into battle sooner. Maggots continued to be used for wound healing in the Napoleonic Wars, in the U.S. Civil War, and in World War I. Once antibiotic drugs and topical ointments gained widespread use, however, the value of maggots was forgotten.

As antibiotic-resistant bacteria and other pathogens are becoming more common, however, we have remembered the value of insect larvae for healing wounds. The most common species in contemporary use is the larvae of the green bottle fly, Lucilia sericata. Though these flies are commonly found outdoors, the flies used for medical purposes are sterile, raised in specialized laboratories. These larvae are interested in eating only dead flesh, not living tissue. Nonetheless, they’re kept in mesh bags such that their heads protrude, but their bodies can’t escape the mesh. In addition to consuming the dead flesh, these larvae produce substances with antibiotic properties, which also alter the pH (acidity) of the wound. Some may also produce substances that stimulate the growth of new healthy tissue.

There’s also some preliminary evidence that some blowfly larvae can release gases that inhibit the growth of a tuberculosis bacterium.

Research

For more than a century, the common fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) has been a star of genetic and chromosomal research, as well as other biological research (e.g., cancer, Parkinson’s disease, insomnia, jet lag, alcohol consumption). It’s inexpensive, small, easy to keep in a laboratory, has a short time between generations, and it reproduces prodigiously. In 2000, its genome was completely sequenced, and it’s 70% similar to the human genome. Perhaps more important, 77% of known disease-related gene sequences in humans also occur in fruit flies.

This species has also been the basis of research for at least six Nobel laureates: 1933, Thomas Hunt Morgan; 1946, Hermann Müller; 1995, Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard and two other researchers; 2004, Linda B. Buck and Richard Axel, discoveries about the fruit-fly’s olfactory system; 2011, three researchers, discoveries about the fruit-fly’s immune defenses; and 2017, three researchers, discoveries about the fruit-fly’s circadian rhythms. By the way, Drosophila is Latin for “dew-loving”), melanogaster is Latin for “black belly.”

Biomimicry

Insects have inspired myriad human inventions and technologies, such as drones, inspired by dragonflies; heat sensors, inspired by black fire beetles; nonfading structural colors used for prints, textiles, paints, cosmetics, cellphone screens, and even solar panels, inspired by blue-colored butterflies and other insects.

Termites have shown particular promise for biomimicry. Termite mounds have ingenious passive air conditioning, created by the structure itself. Even when the outside temperature is intolerable, the inside temperature of the mound is mild and temperate as a draft breezes through. Even in the depths of the mound, the termite queen can prodigiously produce eggs in an oxygen-rich, temperate environment. Not far away are fungal gardens that thrive only if the temperature is close to 90º F. The mound exhales heated carbon dioxide and inhales oxygenated air. In Harare, Zimbabwe, a large office and retail mall emulated the termites’ design, maintaining a temperate environment without artificial air conditioning.

Insect Behavior — Locomotion

Most adult insects have at least two options for locomotion: walking on six legs, flying (most species), swimming (a few species).

Walking

Walking with six legs allows insects to use an alternating tripod gait, in which one half of its steps are taken with the front and rear legs on the left side and the middle leg on the right side; the other half use the front and rear legs on the right side and the middle leg on the left side. In this way, they always have a stable tripod stance with three feet on the ground, while the other three feet are moving forward, for speedy walking.

Figure 18. This beetle is expertly showing how the alternating tripod gait works.

When it’s better to use a different strategy (e.g., while turning, climbing a tree, walking on slippery surfaces, or walking slowly), they may keep four or more feet on the ground at one time. Cockroaches, among the fastest terrestrial insects, will even run bipedally at times. At the other extreme, stick insects (Phasmatodea) tend to move quite slowly, to avoid dispelling the illusion of their camouflage.

Flying

In addition to walking on six legs, most adult insects have wings and can fly — the only arthropods to have wings and the only invertebrates to achieve sustained powered flight. That is, they fly for longer than a short hop, and they power their flight by flapping their wings, not just gliding. Interestingly, both insect wings (two or four) and insect legs (six) are attached at the thorax. Insects started enjoying winged flight about 400 million years ago, the first organisms to fly; the second to fly didn’t appear for another 150 million years or so. Being able to move in all three dimensions made it easier to escape from predators and to find and reach prey, as well as to have easy access to plant nutrients at any height. This ability to fly facilitated many of insects’ evolutionary adaptations.

A group of insects with ancient lineage is Palaeoptera (palaeo-, ancient; ptera, wings), which includes dragonflies and damselflies (order Odontata) and mayflies (order Ephemeroptera). All three kinds of insects have distinctive wing structures, with multiple sets of muscles powering each wing to operate independently, raising and lowering individually. These insects can easily adjust the direction and frequency of their wingbeats and can fly forward, backward, or upside down; they can even hover. With this high maneuverability, they fly a bit more slowly (up to 30 mph), but they’re still highly efficient hunters.