“An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms around Us” by Ed Yong

Yong, Ed (2022). An Immense World : How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms around Us. NY: Random House.

- Introduction: The Only True Voyage, 1–16

- Chapter 1. Leaking Sacks of Chemicals: Smells and Tastes, 17–52

- Chapter 2. Endless Ways of Seeing: Light, 53–83

- Chapter 3. Rurple, Grurple, Yurple, 84–116

- Chapter 4. The Unwanted Sense: Pain, 117–134

(This blog is Part 1 of 3 parts. Parts 2 and 3 will include Chapters 5–13 and back matter.)

Introduction: The Only True Voyage, 1–16

When we humans think about how we sense and perceive the world, we think first of our sight, then maybe our hearing. Then we consider our senses of smell, taste, and touch. Much less often do any of us think about these sensations:

- proprioception (sensations from within our own bodies, such as our intestines)

- vestibular sensations (balance, which Yong calls equilibrioception)

- kinesthetic sensations (movement of our bodies in space)

Many other mammals, especially primates, have similar ways of sensing the world, but quite a few other animals sense the world very differently. For instance, sharks and platypuses can sense faint electrical fields in their environments; robins and sea turtles can sense Earth’s magnetic fields; spiders can sense air vibrations made by a buzzing fly. Even sensations of hearing and sight differ among other animals: Hummingbirds and rodents can hear ultrasonic sounds, while whales and elephants can hear infrasonic ones. Many birds and bees can see ultraviolet light, and rattlesnakes can see infrared radiation.

Figure 01. Is this little female Anna’s Hummingbird listening to ultrasonic sounds we can’t detect?

“There is a wonderful word for this sensory bubble — Umwelt. . . . defined and popularized by . . . zoologist Jakob von Uexküll in 1909. . . . an Umwelt is specifically the part of [an animal’s] surroundings that [it] can sense and experience — its perceptual world” (p. 5, emphasis in original).

In the same physical location, multiple animals could be experiencing multiple Umwelten. In general, the greater the animals’ differences in habitat and diet, the more likely they are to differ in their Umwelten and their sensory systems. Animals who live in ocean abysses or in dark caves will probably need different sensory systems than butterflies and bees. Also, the more remote the location of these animals, the less easily we will be able to study them to understand how they sense the world, let alone how they perceive it.

A few sensational terms Yong uses:

- stimuli — detectable light, sound, chemicals, and so on

- receptors — physiological cells that receive stimuli and transmit them as signals

- photoreceptors receive light stimuli

- chemoreceptors receive chemical stimuli, such as tastes or smells

- mechanoreceptors receive pressure or movement stimuli

- signals — messages about stimuli, which are sent via neurons to be processed in the brain (or to be processed in another way)

- sense organs — where receptors are concentrated for receiving stimuli, such as eyes, ears, nose

- sensory systems — the brain regions that process signals, along with the sense organs that receive the stimuli; combined, they process these stimuli and signals into useful information

Sensory systems consume energy, both to build and to maintain. “No animal can sense everything well” (p. 9). Through evolutionary adaptation, animals prioritize and optimize the senses that are most useful, but they fail to develop, eliminate, or minimize senses that don’t help much for survival and reproduction.

Each animal’s senses affect how the animal perceives the world and interacts with it. For instance, when many animals moved from water to land, they could see much farther into the distance. How did that affect their understanding of the world? Does an animal who can see farther also think differently?

Humans can try to imagine the Umwelten of animals who have similar sensory systems, but it may be beyond our abilities to imagine the Umwelten of animals whose primary senses differ from our own. For instance, bats — fellow mammals — sense the world mostly through sonar. We may be able to imagine flying in the dark, but “seeing” reflected sounds via echolocation is probably beyond our imagination — let alone trying to imagine the Umwelten of spiders or platypuses.

Nonetheless, occasionally, we can convert alien sensations into ones we can sense, such as by translating vibrations or infrasound into audible sound or visible waves. Sometimes, we can infer another animal’s Umwelt, such as by watching a dog follow a scent trail. Though we may never be able to fully perceive the Umwelten of most other animals, we can still relish glimpsing them. Yong celebrates the amazing diversity of these Umwelten.

Chapter 1. Leaking Sacks of Chemicals: Smells and Tastes, 17–52

Smell

“Chemicals . . . are the most ancient and universal source of sensory information” (p. 26). According to Yong, though not all animals can sense light or sound, and few can detect electric or magnetic fields, every organism can detect chemicals (odors or tastes). “Even a bacterium . . . can find food and avoid danger by picking up on molecular clues from the outside world” (p. 26). Bacteria can also send chemical signals to one another, and those signals can be detected by viruses — which may or may not be living organisms because they can’t survive independently.

Odorants are the chemical molecules containing a scent that can be detected; odors are the sensations produced by odorants. My stinky socks contain odorants; my dog Sweetie enjoys sniffing the odors wafting from my stinky socks’ odorants. Like other dogs, when Sweetie inhales, most of the air flows down to her lungs, but some of it is diverted backward to a labyrinthine chamber of thin bones, coated with an olfactory epithelium. The olfactory epithelium contains myriad chemoreceptive neurons; each chemoreceptive neuron is distinctly attuned to particular odorant molecules. When a neuron detects a target odorant, it directly signals the brain’s olfactory bulb, where the odor information is processed.

Though I and other humans have pretty good senses of smell, Sweetie outshines us, with dozens of times more olfactory neurons, each of which detects almost twice as many different odorants. Whereas I inhale and exhale odors through my nose, Sweetie’s nose is structured to allow odors to linger, merely adding to them with each new inhalation. Another problem with my nose, compared with Sweetie’s: It’s much farther from the ground. My behavior’s a problem, too: I tend not to lean over to give new people or places a thorough sniffing. On the other hand, we shouldn’t underestimate our own ability to sense smells. Like dogs, we humans have superlative ability to discriminate among different odors — for some odorants, sometimes even more ably than dogs can. (My own opinion: We can use language to help us differentiate among smells; Yong notes that the Jahai people of Malaysia have a rich vocabulary for smells and can readily distinguish among smells.)

Attempts to quantify dogs’ scent detection have been all over the map, depending on the dogs, the methods, the odorants, and so on. It may be better just to focus on what they can do with their sense of smell, such as finding bombs, landmines, avalanche victims, living or dead people or other animals, diseases in crops or in humans, bedbugs, leaks in oil pipelines, pollutants, tumors, turtle nests, animal scat, and much more. For a dog, a walk or a visit to a new location is an opportunity for exploration, fascination, and delight.

Figure 02. Yong mentioned a dog researcher who recommends taking your dog out for dedicated smell walks, on which you stop whenever your dog stops and let your dog sniff to its heart’s content. These walks may not be great physical exercise, but it’s great mental exercise and a true joy to your dog. On the NPR show A Way with Words, cohost Martha Barnette takes her dog on daily “sniffaris” to check its “peemail.”

Lightwaves travel in straight lines; odorants don’t. Smells waft, swirl, seep, meander, and diffuse. Smell can turn corners, traveling through air and water. Smells can linger long after they’re launched, revealing the past, and they can herald an arrival ahead of time, foretelling the future. Some animals intentionally send smell signals, such as pheromones, but all of us (except puff adder snakes!) leak chemical odorants, even if we’d rather not do so. Sensitive noses can detect not only our presence, but also our health, our recent meals, and more. (My dog Mechan used to smell my breath when I returned from having a meal away from home, and she would give me scolding looks when I had eaten something she would have liked to share with me.)

Lightwaves and soundwaves can be measured, but odorants can’t; they’re ephemeral, hard to define or even to describe. Yong gives numerous examples of the ambiguities of odorants, even odorants with nearly identical chemical molecules. To complicate matters even further, odorant receptors differ not only across species, but even across individuals within the same species. Odorants that one person readily detects, another can’t detect at all; odors that repel some people attract others. Our genes will make the same molecule smell different.

We animals emanate various kinds of odors. Many are simply manifestations of our identity and physiology, our recent meals, activities, locations, and so on. Some odorants signal membership in a group; clonal raider ants’ odorants say, “I’m a colony-mate,” or “I’m an intruder.” Some odorants are pheromones, which we release to signal messages to members of our own species. For instance, pheromones often signal when species members are available to mate. Pheromones can also signal an entire colony of ants to come to the aid of a colony-mate, or pheromones can mark a trail leading to desirable food. Ants are champs of odorant reception: Most ants have 300–400 odorant receptor genes (clonal raider ants have 500!), overshadowing most honeybees (140 such genes) and fruit flies (60).

How do our Umwelts differ from those of other animals? For starters, female lobsters attract males by producing pheromone-rich urine, which they squirt into the males’ faces. Male mice’s urine has potent pheromones that attract females.

Many organisms use odorants to deceive. The caterpillars of blue butterflies smell like ant grubs, prompting red ants to take care of these caterpillars. Spider-orchid odorants mimic the sexual pheromones of male bees to attract them.

At the other end of the size spectrum, elephants rely on their keen senses of smell. Elephants have 2,000 olfactory receptor genes and a huge olfactory bulb. “Their lives are dominated by smell. . . . No other animal has a nose so mobile and conspicuous, and so no other animal is as easy to watch in the act of smelling” (p. 34). Whatever the elephant is doing, if it’s moving, it’s moving its trunk. Both African and Asian elephants can easily detect subtle odors and can learn to identify unfamiliar smells. They recognize familiar individual elephants and humans and can differentiate the odors of groups of persons who harm them from groups of persons who don’t.

After being separated, when elephants reunite, they flap their ears and make throaty rumbles, exuberantly urinating, defecating, and exuding aromatic liquids from glands behind their eyes. Within their family, elephants often closely inspect each other’s “glands, genitals, and mouths” (p. 35). In addition to affirming social bonds, scents convey other important information. Dung and urine left along trails provide historical and updated information about routes, for other elephants to detect. During long migrations, scents can provide guidance. Elephants have been observed detecting distant rain, and at least one researcher believes that elephants can detect the scent of buried water and can use that knowledge to dig wells in times of drought.

Mammals and insects aren’t alone in having remarkable scent detection. Salmon can use smell alone to find their way home to their natal stream after spending years away at sea. In rain forests, whip spiders can detect smells on the tips of their long front legs to find their way home. Many landscapes can better be described as “odorscapes.” For centuries, however, an entire class of animals was believed to lack much sense of smell: birds.

In the 1960s, technical illustrator Betsy Bang methodically dissected and sketched the nasal passages and brains of more than 100 bird species, closely examining and measuring the olfactory bulbs of their brains. She saw that these birds had the same kinds of “convoluted scrolls of thin bone, much like what lurks within a dog’s snout” (p. 39) and inferred that most birds must be able to smell. Some birds had remarkably large and well-developed smell apparatus — such as North American Turkey Vultures, New Zealand kiwis, and oceanic tubenose seabirds.

Meanwhile, physiology professor Bernice Wenzel was studying homing pigeons when she noticed that they responded with rapid heart beats and buzzing olfactory neurons when they caught a whiff of scented air. She then examined the responses of “turkey vultures, quails, penguins, ravens, ducks,” found the same excitation, and concluded that many species of birds can smell.

Back to tubenoses. Tubenoses (e.g., albatrosses, petrels, shearwaters, fulmars) have tubelike nostrils that readily detect the scent of krill and other sealife as the birds glide over the waves. Gabrielle Nevitt confirmed that tubenoses detect dimethyl sulfide (DMS), released by plankton. Krill eat plankton, so wherever tubenoses detect DMS, krill are sure to be present. Plankton — and krill — appear only in pockets and other particular places on the ocean, so being able to detect it by smell offers tubenoses an advantage. When tubenoses are chicks, they’re reared in dark burrows, where they rely on smell, not vision.

Figure 03. Tubenoses, such as these Southern Royal Albatrosses, have tubelike nostrils that keenly detect the scent of their favorite prey in the vast ocean. Source, JJ Harrison (https://www.jjharrison.com.au/), Southern Royal Albatrosses (Diomedea epomophora) ‘beaking’; East of the Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania, Australia; 2 September 2012, 12:16:09. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. You are free to copy, distribute, and transmit the work if you give appropriate credit. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Southern_royal_albatross for more information about this species of tubenose. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Procellariiformes for more on all species of tubenoses.

Penguins and reef fish are also attracted to DMS, as are sea turtles. Among reptiles, snakes are better known for their keen sense of smell, which they detect through their forked tongue. Snake tongues can be longer and wider than snake heads, though they have no taste buds or taste receptors. Instead, their tongues tell them whether what they’re smelling is worth eating. The snake’s tongue collects odorous chemicals, then presses the collected odorants against the snake’s vomeronasal organ — where chemoreceptors connect to the brain’s olfactory centers.

Why a forked tongue? With stereo smelling, the snake can compare the chemical traces in two places simultaneously; stereo smelling allows the snake to more definitively identify the location of odors. Snakes also inhale smells through their nostrils (as dogs do), but these inhaled odorants aren’t as important; they may, however, alert a snake to flick its tongue at a possible interesting scent. Once a promising scent is detected, the snake will swirl each fork of the tongue, moving the air to draw in odorants from each side.

Venomous snakes can envenomate prey, such as a rodent, then let the victim try to escape. While envenomating the prey, the snake learns its individual scent and injects a chemical prompting the victim to release odorants. The snake can then follow the scent to find the fresh corpse. Venomous snakes can also identify their own venom, distinguishing it from a victim envenomated by a different snake.

Nonvenomous snakes use smell, as well. For instance, a male garter snake can follow the pheromone trail of a female snake. Once he finds her, his tongue flicks can assess her health, as well as her size. Lizards use smell, too, but they do so differently. Lizards flick their tongues (which may or may not be forked) just once, extending the tongue tips to scrape the ground and then retract.

Taste, too

Both gustation — the sense of taste — and olfaction (smell) involve detecting chemicals through chemoreceptors. Smells are detected in the air, perhaps wafting from distant locations, but tastes must be detected through direct contact with the liquid or solid containing the gustatory chemicals. The distinctions aren’t quite that simple, though. Smells can also travel through water, such as when salmon follow scents to their natal stream. And some insects can detect pheromones on one another by touching each other directly.

Taste responses seem to be reflexive, such as when we immediately reject bitter substances. We can learn to like some bitter tastes, though, such as coffee or dark chocolate. Smell responses seem to be based on experience. Humans don’t react with disgust to poop or sweat as infants; we learn those reactions as we have experiences teaching us to respond with disgust.

Smells are widely varied — almost infinitely so — whereas there are just five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami (savory, like mushrooms, cheeses, meats). Smell also seems to have much more varied uses, too — finding a mate, finding a pal, detecting an enemy, finding food, finding home, and so on. Taste is pretty much dedicated to decisions about food: Do I want to eat this or not? Taste sensation is not universal. For instance, snakes don’t bother with taste sensations because they already know all they need to know about food, based on its smell.

Figure 04 (a&b). Four of the five key tastes: sweet (fruits, cookies), sour (lemons, lemon juice), bitter (coffee), and umami (cheese, tomatoes); cheese has a little salt, so maybe all five?

Not all birds can detect taste well, but hummingbirds and songbirds (e.g., robins, jays, cardinals, sparrows, finches, starlings) can sense sweetness. Birds, mammals, and reptiles sense taste with their tongues, as that’s where they make decisions about whether to eat a particular food. Other animals have organs in other locations for detecting taste. Bees, mosquitos, and flies can detect taste through their feet. Parasitic wasps detect taste through their ovipositors to know where to implant their eggs. Some flying insects have taste receptors on their wings, to alert them when yummy food is nearby.

According to Yong, catfish “are swimming tongues. They have taste buds spread all over their scale-free bodies, from the tips of their whisker-like barbels to their tails” (p. 50). These taste buds are finely tuned to detect umami — sensing the presence of amino acids, the building blocks of proteins. They’re less able to detect sweetness, so they wouldn’t enjoy being dipped into a vat of chocolate syrup. Weird, right? Carnivores (e.g., cats, hyenas) can’t detect sweetness either. On the other hand, neither pandas nor vampire bats can detect umami, but pandas, koalas, and some other herbivores have a keen ability to detect bitter compounds (common in toxins). In contrast, sea lions and dolphins (which swallow their fishy prey whole) don’t detect bitterness. An animal’s taste sensations seem to follow its dietary choices.

Intriguingly, animals see by using opsins, which are modified chemical sensors. “In a way, we see by smelling light” (p. 52).

Chapter 2. Endless Ways of Seeing: Light, 53–83

Yong defines light in physics terms, which exceed my ability to grasp, let alone explain. It costs a lot to build and maintain any sensory system, and eyes are especially costly. Even when our eyes are closed, they’re using energy just so they’re prepared to see when needed. “Perhaps the most wondrous thing about light is that we sense it at all” (p. 57).

Unlike orb spiders, jumping spiders don’t weave webs, where they wait to sense prey through vibrations. Instead, jumping spiders actively pursue and stalk their prey, relying on vision. These spiders can see almost 360º, missing only a spot directly behind their heads. Their four pairs of eyes compose almost half the volume of their heads, and they’re “the only spiders that will turn and look at you routinely” (p. 53). Portia jumping spiders “flexibly [switch among] sophisticated hunting tactics” (p. 54).

Fun fact: “Baby jumping spiders are transparent. With good lighting, you can see their eye tubes moving about inside their heads” (p. 55).

In jumping spiders, the largest and sharpest pair of eyes face forward, seeing as well as pigeons or small dogs. The retinas of these two eyes can diverge, looking separately, or can converge and look at something together; they can also rotate together, clockwise or counterclockwise. Even so, their field of view is narrow — which is where the other six eyes help out. Though these “secondary” eyes can’t move, they readily detect motion and make it possible for the spider to track moving objects. That is, where our eyes can simultaneously focus on something and detect motion in the periphery, jumping spiders use different sets of eyes for these two abilities.

We humans have just two same-sized eyes, located on our heads, both facing forward — which is peculiar among animals. Animal eyes can number from one to hundreds; sizes of eyes can range from nearly imperceptibly small (e.g., in fairy wasps) to the size of soccer balls (in giant squids). Eyes can be found on legs, arms, mouths, and armor. An eye can have a single focal point, two focal points, or asymmetrical focal points. Animal eyes can see with high resolution (acuity) or poor resolution, with high sensitivity (in near-darkness) or low sensitivity (only in intense brightness), at ultrafast speed or only at near-time-lapse speeds, in one direction or in multiple directions, with changing sensitivity across the span of a day, or with increasing resolution over a lifetime.

[There are two basic types of photoreceptors: rods, which are highly sensitive to almost any amount of light but don’t have high acuity and can’t detect color, and cones, which require bright light to see but have high acuity and can detect color (in animals who can see color). Animals with an abundance of rod photoreceptors in the retina have high sensitivity and can see well in dim light, but they don’t have great visual acuity. Animals with an abundance of cone photoreceptors in the retina have great visual acuity in bright light and may be able to see color, but they can’t see well in dim light. Having an abundance of rods is great for nocturnal hunters such as owls; having an abundance of cones is great for diurnal hunters such as hawks. — SDH]

Humans, jumping spiders, and squids have single-lens eyes, which focus light on a single retina; invertebrate arthropods such as insects and crustaceans have compound eyes, with perhaps thousands of ommatidia, “tiny independent photoreception units that consist of a cornea, lens, and photoreceptor cells [that] distinguish brightness and color” (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compound_eye for some cool pics of compound eyes). Each of the ommatidia may be pointed in a slightly different direction. Compound eyes don’t have good image resolution (sharpness), but they have a very wide field of view and can easily detect fast movements.

Despite the astonishing diversity of eyes, all of them contain photoreceptors, cells that can sense light, and all of them do so using proteins called opsins. Each opsin protein hugs a chromophore, its partner molecule, usually made from vitamin A (found in any healthy diet). As each hugged chromophore absorbs light energy (photons), it changes shape, which reshapes the opsin, setting off a chemical chain reaction that triggers an electrical signal to travel down a neuron. That is, light triggers the chromophore to prompt the opsin to ignite the chemical reaction that starts the electrical signal that fires up a neuron that tells the brain it’s seeing something. (A bit Seussian, isn’t it?) Though there are thousands of different opsin proteins in different animals, and myriad kinds of eyes use opsins in a diversity of ways, all opsins have this same basic relationship to light.

How did this diverse array of eyes evolve? Step 1. Develop light-sensitive photoreceptors, which simply detect whether light is present. Many cephalopods (octopuses, cuttlefish) have photoreceptor spots all over their skin, which may help them change their skin coloration, using chromatophores (pigment-containing cells).

Step 2. Add some kind of shade near the photoreceptors — a pigment or other barrier, which shields the photoreceptors at some angles, so they can infer the direction from which the light is coming. Japanese Yellow Swallowtail Butterflies have photoreceptors on their genitals, which can help males in mating and can help females to position their egg-laying tube on a plant’s surface.

Step 3. Form multiple clusters of shaded photo receptors. The animal can process these multiple sources of light coming from multiple directions into information about the world and perhaps even low-resolution images of the world. Step 4. Boost the resolution of these images. According to Yong, “The rise of high-resolution vision might explain why, around 541 million years ago, the animal kingdom dramatically diversified, giving rise to the major groups that exist today” (p. 59).

Though all photoreceptors use opsins, photoreceptor-based eyes have separately evolved countless times across species — at least 11 times in jellyfish alone. Among many living species, their eyes are well adapted for the needs of that species, but they’re not nearly as sophisticated as ours. For instance, starfish — which have eyes on the tips of each of their five arms — have eyes that readily detect the presence of large objects, so they can slowly crawl toward a coral reef. Their eyes don’t have high resolution, can’t see color, and don’t detect rapid movements. But they don’t need to. For the starfish, its armtip eyes do the job it needs to have done.

Starfish eyes would never work for primates who want to catch insects zipping around on trees. Or for humans who want to read books. Which is why we don’t have starfish eyes — though having eyes on my fingertips might be nice, . . . as long as I didn’t poke them while I’m typing . . . .

We humans can be biased to see the world — and the world of other animals — through our own sharp lenses. For instance, some scientists had hypothesized that zebra’s stripes are adaptive because it makes it harder for lions and hyenas to detect their outlines. Nope. These predators hunt at night and have relatively poor vision, so they probably can’t even see the stripes. A lion’s vision is just slightly better than the vision of a legally blind human.

[Fun fact: Zebra stripes seem to deter annoying flies from being able to land on a zebra to bite it. See Zebra – Wikipedia for more information. — SDH]

Human eyes have sharper vision than most animals. Birds of prey (eagles, hawks, etc.) are the only animals who can see substantially better than we can. Other primates come close to us, and octopuses aren’t too far behind, but most other animals have much poorer vision. All insects, most fish, and about half of all birds (including barn owls) have vision comparable to (or worse than!) humans considered legally blind. Disappointingly, though most insectivorous birds can spot the brightly patterned wings of butterflies, the butterflies themselves probably can’t detect their own brilliant designs.

Figure 05a-d. Diurnal birds of prey (above), such as this Ferruginous Hawk and this Red-tailed Hawk have astonishing visual acuity, even better than human vision, but they have poor visual sensitivity, not able to see well in dim light. Nocturnal birds of prey (below), such as this Great Horned Owl and this Barn Owl, have poor visual acuity, but phenomenal visual sensitivity, spotting prey in dim light.

One reason for the limited resolution of the eyes of insects’ and crustaceans is their compound eye structure. The very structure of the compound eye limits its resolution. “For a fly’s eye to be as sharp as a human’s, it would have to be a meter wide” (p. 64).

Another factor limiting acuity is the tradeoff animal eyes must make between sensitivity — the ability to detect the presence of objects in near darkness — and acuity — the ability to see objects sharply in bright light. The cone photoreceptors that work well in bright light, offering high visual acuity, can’t detect images in low levels of light; the rod photoreceptors that work well in dim light, offering high sensitivity, don’t provide much acuity or sharp details. Eagles and other raptors see superbly in bright light, but they can’t see much after the sun sets. After sunset, lions and hyenas can see well enough to hunt their prey, many of whom can’t see well at night.

Most bivalves (e.g., mussels, oysters) don’t have any eyes. Scallops, however, have dozens of eyes, up to 200 in some species (please see the myriad tiny bright blue eyes of the Argopecten irradians scallop, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scallop#/media/File:Argopecten_irradians.jpg). Each eye is attached to a movable tentacle, and each eye has two retinas, with each retina containing thousands of photoreceptors. (It’s possible that one of the retinas is better at detecting moving objects and the other is better at choosing habitats.) Interestingly, a researcher who studies scallop vision has concluded that though each eye has good spatial resolution, the scallop itself probably has poor spatial vision, perhaps because it doesn’t have a brain set up for seeing well. Even the researcher is puzzled by the scallop’s eyes and its vision.

Even more puzzling than the scallop is the brittlestar, which has no eyes but has thousands of photoreceptors up and down its slender arms. They lack brains, too. At night, the photoreceptors don’t have spatial vision. Other creatures on the ocean floor, sea urchins, have photoreceptors on their tube feet, which are shaded by their spikes or their exoskeleton, but they can still detect dark shapes.

Less unfamiliar than these invertebrates are birds, such as raptors. Yet their vision can puzzle us, too. They have such keen vision that they can spot prey at great distances. Yet they periodically crash into giant wind turbines, which you’d think they could easily see. It turns out that the visual fields of bald eagles, vultures, and other large raptors cover most of the space on either side of their heads. Unfortunately, however, these raptors have big blind spots directly above their heads and directly below them. While flying, the raptor points its head downward, to search for prey, so that the blind spot above its head is actually pointing straight ahead. While searching for prey these raptors can’t see what’s directly in front of them.

Unlike most birds, we humans have both of our eyes facing forward, with overlapping visual fields. As a result, we have excellent depth perception, but we can’t see anything behind us, and we see very little at our sides, unless we turn our heads. Owls share our viewpoint, but most other birds don’t.

Herons can see 180º vertically, from their feet to above their heads, so while holding their bill horizontally, they can spot a fish swimming at their feet. A mallard can see 360º horizontally, as well as above it, so while flying, it can see all of the sky through which it’s moving and through which it has moved. Imagine how this affects their Umwelt. While we move into the environment we see ahead, these birds move through the environment they see all around them.

In human eyes, photoreceptors are located on our retinas; each retina has an area where the photoreceptors are most dense — the fovea. In other animals, this area can be called the acute zone, the area of sharpest vision. Raptors (eagles, falcons, etc.) have two acute zones in each eye. One acute zone looks forward, and a sharper acute zone looks sideways at a 45º angle. Other animals with two or three acute zones per eye include elephants, hippos, rhinos, whales, and dolphins.

Some raptors have a preferred eye for following prey, turning their heads slightly to keep the preferred eye focused on the prey. Many other birds have eye preferences, too. For instance, a female Argus Pheasant may keep one eye closely focused on the courtship display of a male — she may appear to be looking away from him, with her bill pointed forward, but her side eye is keenly watching him.

Many animals (e.g., livestock, rabbits, red kangaroos, fiddler crabs, water-strider insects) have superlative panoramic vision of the entire horizon. They rarely need to look around or even to look up or down, as they see all they need to see just holding their heads still. An alternative way of seeing is the chameleon, who can rotate each eye independently. The Anableps anableps fish partitions each of its two eyes, so that the top half of each eye sticks out of the water and is adapted for seeing through air, and the bottom half of each eye stays below the water surface and is adapted for seeing through water.

In the deep ocean, cock-eyed squids can simultaneously look upward and downward, with each of its tubular eyes pointing in different directions. Its upward-pointing eye looks for silhouettes of other animals above it and is twice as big as its downward-pointing eye, which scans for bioluminescent flashes below.

The deep-sea crustacean Streetsia challengeri (interesting name, right? see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyperiidea#/media/File:Streetsia_challengeri_(YPM_IZ_103944).jpeg) has fused its left and right eyes eyes into a single cylinder containing about 2,500 ommatidia; it can see 360º in nearly every direction — except ahead or behind! (“The eye optimally combines acuity with sensitivity” from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/203400/) (For more info on this species, see also https://www.sealifebase.se/summary/speciessummary.php?id=25232)

The speed of light is defined as the fastest in the cosmos, but the speed of processing light in photoreceptors, sending that information to the brain, and reacting to that information is

M_U_C_H ____S_L_O_W_E_R.

Scientists measure the speed of at which the brain can process light as critical flicker-fusion frequency (CFF). CFF is the point at which a series of light flickers seem to merge into a single steady flow of light. Similarly, we see films as having a single fluid motion, though they’re actually a series of individual frames. If you’ve seen traditional fluorescent lights, you may even have sensed the flickering at 100 Hz (100×/second).

Humans have a CFF of about 60 frames/second (60 Hz). Most flies have a CFF about 6× as fast, about 350 Hz, with some flies processing their vision even more speedily. By comparison, dogs are a bit faster than we are (75 Hz), and cats are a bit slower (48 Hz). Scallops process vision at about 1–5 Hz. Many birds have much faster vision, with the insectivorous Pied Flycatcher topping out at 146 Hz, “the fastest vision of any vertebrate that’s been tested” (p. 76). Given how quick flies are, insectivorous birds need speedy vision. We can only begin to imagine the Umwelt of other animals: Do scallops see our movements as a frenetic blur of speed? Do flies see our movements as so glacial as to seem almost immobile?

At the extreme end of light sensitivity is Megalopta genalis, a nocturnal sweat bee of the Panamanian rainforest. Rainforests are relatively dark even in daytime; on a night with a full moon, the available light is 1,000,000× less! And when no moon shines, starlight is 100× less bright than in moonlight. Throw in some occasional clouds, and it’s dimmer still. Yet somehow this tiny species of bee can leave its nest, fly to all of its favorite flowers, gather pollen, and swiftly fly back to its nest. (According to Wikipedia, their eyes are 27× more sensitive to light than the eyes of diurnal bees; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Megalopta_genalis for pictures and more information.) Two of its adaptations are (1) several different photoreceptors combine their pixels to make megapixels, and (2) photoreceptors may also gather more information during a longer exposure before firing, like a camera taking pictures in low light. Recalling the tradeoff between sensitivity and acuity, vision is probably grainy, but it’s good enough to see in near-dark.

Another strategy for seeing in the dark is used by cats and many other mammals: Behind each retina is a tapetum, a reflective layer that bounces back any light that gets past the photoreceptors, giving the photoreceptors a second chance to gather photons. Huge eyes and enormous pupils are another option. In tawny owls and tarsiers (small primates), each eye is larger than its brain — each one! And those aren’t the biggest eyes on the planet.

In the deep ocean, 100 meters (>300 feet) below the surface, light is just 1% as intense as it is at the ocean’s surface, and in another 100 meters down, it’s another 50× less bright. “At 300 meters, it’s as dark as a moonlit night” (p. 79). On descending further, the living organisms produce their own bioluminescence, and by 1000 meters below the surface, no animal’s eyes can function. The total darkness only occasionally sparkles with bioluminescence.

Giant squids have the largest and most sensitive eyes of any organism on Earth — up to 10.6″ in diameter. To get an idea of relative size, the eyes of blue whales are the next largest in size, and they’re only half as large as the eyes of a giant squid. Swordfish have eyes that are 3.5″ in diameter — the largest fish eyes in the world — but much smaller than a giant squid eye’s pupil. Why do giant squids need such giant eyes? To spot sperm whales. Mature sperm males can be more than 50 feet long, and their favorite food is giant squid, as well as colossal squid. Sperm whale eyes are the biggest eyes of all toothed whales, but they rely on sonar more than on vision to find food. (According to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sperm_whale these whales use vision to find prey.)

Elephant hawkmoths can’t see in the deep ocean — nor would they want to — but they can see in the dark. In fact, they can see colors in the dark.

Chapter 3. Rurple, Grurple, Yurple, 84–116

Most animals — including dogs — see a different range of colors than most people see. Light reaches us in wavelengths; humans can see wavelengths starting at 400 nanometers, “violet” (the tiniest arc of the rainbow) and stopping at 700 nanometers, “red” (the biggest arc of the rainbow). Our ability to see light depends on the opsin proteins in our photoreceptors (mentioned in the previous chapter). Opsins are highly diverse, and each opsin specializes in absorbing a particular wavelength of light. Normal human color vision depends on three kinds of opsins in the cone photoreceptors in our retinas. The cones and their opsins are called “long” (for red wavelengths), “medium” (for green wavelengths), and “short” (for blue wavelengths). Light reflecting off a strawberry will strongly stimulate the long (red) cones, somewhat stimulate the medium cones (green), and very slightly stimulate the short (blue) cones. The opposite will be true for light reflecting off a blueberry.

To further complicate our understanding of color vision, our neurons are not only excited by some colors but also inhibited by some other colors. Neural opponency allows us to discriminate a wide range of colors, using just three types of opsins in our photoreceptor cones. Our ability to see colors actually happens in our brains, as a subjective experience. People who suffer some kinds of brain damage may not be able to see colors, despite having completely normal eyes.

The retinas of many people aren’t able to sense color and are considered monochromats. Many animals are also monochromats, having only rod photoreceptors, without cone photoreceptors. Sharks, raccoons, and whales have just one type of cone, so even though they can detect color wavelengths, they’re still monochromats because they can’t compare colors. Cephalopods (cuttlefish, octopuses, squids) have monochromatic wavelength-specific photoreceptors, but with only one type of receptor, they’re monochromats, too. Doesn’t it seem crazy that they can’t see their own skin’s chromatophores changing colors to camouflage them? (Their skin has specialized cells that reflect light from the environment; also, their skin may be able to sense light directly. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cephalopod#Vision for more information.)

Organisms don’t need to see colors in order to navigate, find food, find mates, or communicate. What’s advantageous about seeing color? It turns out that being able to see different wavelengths of life makes a flickering world of light and shadow more comprehensible. Being able to see at least two different kinds of wavelengths makes the world easier to understand. In fact, most mammals (e.g., dogs, horses) are dichromats, having just two kinds of photoreceptor cones (blue and yellow). (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Color_constancy for more on how color vision makes the world easier to understand.) Though some color-blind humans are monochromats, most are dichromats, lacking just one of the types of photoreceptor cones other people (trichromats) have. (Being able to see color is also beneficial for any animal that eats fruits; a green fruit tastes very different than a colorful ripe fruit. On the other hand, monochromats and dichromats can spot insects more easily than trichromats, who are confused by camouflage colors.)

Early primates were probably dichromats, too (blue and yellow). About 29,000,000–43,000,000 years ago, a mutation added a third kind of opsin to our photoreceptor cones. Modern primates — monkeys, apes, humans — have three types of photoreceptor cones and can see trichromatically. “A monochromat can make out roughly a hundred grades of gray between black and white. A dichromat adds around a hundred steps from yellow to blue, which multiplies with the grays to create tens of thousands of perceivable colors. A trichromat adds another hundred or so steps from red to green, which multiplies again with a dichromat’s set to boost the color count into the millions. Each extra opsin increases the visual palette exponentially” (p. 90).

We trichromatic humans stop at three opsins. Some other animals go beyond three, or they have different opsins than we do. Among animals who can see colors, most have opsins and photoreceptor cones for sensing ultraviolet (UV) light, with wavelength ranges of just 10–400 nanometers. Scientists first observed this ability in ants and bees, then in other insects, as well as many birds, reptiles, fish, and mammals (dogs cats, pigs, cows, reindoor, bats, rodents, etc.). A few humans can see UV light, too, if they lose one or both of their eyes’ lenses. For nearly all other humans, however, our lenses and corneas block our ability to see UV light.

The ability to sense UV light means that the visible Umwelt of most other animals looks very different than ours does. Fish can more easily spot plankton against a UV-rich watery environment; rodents can more easily detect birds silhouetted against a UV-brightened sky; bees can readily notice the distinctive UV patterns of many flowers. More than 90% of songbirds (e.g., mockingbirds, barn swallows) also have distinctive UV-reflecting plumage, often creating sexual dimorphism (different appearance in females vs. males) among birds where we see only uniformity.

Fun fact: Predators such as kestrels do not use UV light to track prey such as voles. Urine doesn’t reflect more UV light than water does; it’s not visible from a distance, such as while flying overhead.

The ability to detect UV light doesn’t necessarily mean being tetrachromatic (having four types of opsins and photoreceptor cones, able to see four different colors). For instance, bees and almost all butterflies sense UV light + blue + green, but not red. Hummingbirds, however, are true tetrachromats, with opsins and photoreceptor cones that can sense red, green, and blue, as well as either violet or UV light. Seeing a fourth color isn’t just additive; it’s multiplicative, an exponential difference in color vision.

With our three types of photoreceptor cones, when something stimulates both our red and our blue photoreceptor cones, we perceive red–blue, which we call purple. A hummingbird (and other tetrachromatic animals) can see

- UV–red — which Yong calls “rurple”

- UV–green — which Yong calls “grurple”

- UV–red–green (a shade of yellow) — “yurple”

- UV–red–blue — “ultrapurple” — which is the bib color on a Broad-tailed Hummingbird male

- and so on

Unlike the vast majority of butterflies, female Heliconius butterflies are tetrachromats, not trichromats. Intriguingly, the females have blue and green opsins and photoreceptor cells, plus two types of UV opsins, each able to detect a different portion of the UV range of wavelengths. A few rare human females (and even rarer males) are tetrachromats, too, readily detecting colors differentiated only by having a fourth type of opsin and photoreceptor cone.

Figure 06. Unlike most other butterflies, female Heliconius butterflies are tetrachromats. (I’m not really sure this Heliconius cydno, “Cydno Longwing,” is a female, but there’s a 50:50 chance that she is, right?)

Scientists now think that the first vertebrates to evolve were probably tetrachromats. Dinosaurs, the ancestors of birds, were probably tetrachromats, as well. When the first mammals evolved as a separate class, they were nocturnal, having little need for tetrachromatic vision. Over time, these mammals lost two of their types of opsins and photoreceptor cones, becoming dichromatic.

Among other animals, “color vision varies considerably among the 6,000 species of jumping spiders, the 18,000 species of butterflies, and the 33,000 species of fish” (p. 103). As one example, bluebottle butterflies have 15 classes of opsins in their photoreceptor cones, for which 4 are for tetrachromatic vision, and an additional 11 are probably used “to detect very specific things in narrow parts of the visual field” — WOW! According to Yong, having four types of opsins and photoreceptor cells probably allows an animal to see everything seeable in the world. He calls any more “wasteful and an extravagance” (p. 104).

And there is indeed a highly extravagant animal: the mantis shrimp (aka, stomatopod), an order of carnivorous marine crustaceans (containing 500 species) related to prawns and crabs. Each of this shrimp’s two compound eyes contain between 11 and 16 distinct kinds of photoreceptors, 4 of which are dedicated to distinctive wavelengths of UV light! Incomprehensible for us human trichromats. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantis_shrimp for photos and additional information; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantis_shrimp#/media/File:Odontodactylus_scyllarus_eyes.jpg for a closeup photo of eyes.)

Fun fact: A mantis shrimp’s punches “are the fastest and most powerful in the world” — about 50 mph, in water. About 3.9–15″ (20–38 cm), these shrimp can injure a human thumb or punch through an aquarium.

Don’t feel too envious of the mantis shrimp’s color vision, though; they actually have a lot of trouble discriminating among different colors. We humans can tell the difference between colors for wavelengths that are 1–4 nanometers apart; mantis shrimp have trouble differentiating between colors with wavelengths that are 12–25 nanometers apart. According to one researcher, mantis shrimp consolidate “all the varied hues of the spectrum into just 12 colors”; others say “they might use different kinds of color vision for different tasks” (p. 108). Their brains are pretty small, too. (Some visual information may be processed before it reaches their brains.) Exactly how they see color awaits further research, and these pugnacious shrimp are extremely challenging to study.

Even without considering their color vision, their two compound eyes are fascinating: They move in any direction, and can rotate clockwise or counterclockwise in three dimensions, each eye moving independently, rarely in the same direction. In addition, each eye has three parts that give it trinocular vision — yes, trinocular — giving each eye superlative depth perception for gauging distance independently.

Fun fact: When we’re moving, “our eyes actually fix on specific points ahead of us, rapidly flicking from one to the next. These flicks, or saccades, are some of the fastest movements we make, . . . as they’re happening, our visual system shuts down. Our brains fill the millisecond-long gaps to create a sense of continuous vision, but that’s an illusion” (p. 111, emphasis added).

Mantis shrimp have another trick; they actually share this trick with most other crustaceans, as well as most insects and cephalopods: They can see polarized light.

To me, understanding polarized light is like understanding how electricity works — it’s magic. For an explanation, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polarization_(waves) .

The type of polarized light that some animals can see is linear polarized light, but quite a few species of mantis shrimp can also see circular polarized light, which is highly unusual (for information on circular polarization, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circular_polarization; for more on how mantis shrimp see polarized light, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mantis_shrimp#Polarized_light). It’s thought that these shrimp may use polarization cues as additional colors.

In South America, a single species of strawberry poison frogs has 15 strikingly different appearances, such as lime green with cyan, or orange with black spots. All are poisonous, but the most toxic variants are also the most visible to birds, who have tetrachromatic vision to notice the color variants. According to some researchers, the coloring of an animal indicates something about the visual abilities of its chief predator.

Intriguingly, the same thing happened with flowers. Insects and other pollinators were trichromatic long before flowers evolved. Once flowers came along, however, the flowers evolved colors and patterns to attract their pollinators. The flowers’ visual appearance was adapted to target the visual abilities of their pollinators. We trichromatic humans are beneficiaries of those adaptations.

Chapter 4. The Unwanted Sense: Pain, 117–134

Almost all animals use nociceptors to sense body damage caused by burns, pinches, harsh chemicals, wounds, breaks, inflammation, or other harms. Nociceptors can vary in number, size, excitability (how easily they’re triggered), and transmission speed. Sense scientists distinguish between nociception — the sensory process by which our nervous systems detect damage to our bodies — and pain — the subjective experience of suffering because of this damage. Usually, nociception can be measured objectively by observing the damage; pain is a subjective experience and cannot be measured objectively. This distinction makes it tough to know when another animal (or a nonverbal human) is experiencing pain, other than by inferring it from its behavior (or observable physical damage). Pet owners, veterinarians, and researchers all face the difficulty of knowing when, where, and how an animal is experiencing pain.

In addition, researchers face an ethical dilemma: How can they avoid inflicting needless pain on any animal while investigating how an animal experiences pain. By studying fish, we now know that fish definitely experience pain when hooked by a fisher. The researchers studied as few fish as possible (while maintaining statistical rigor) and anesthetized the fish as soon as possible. People who catch fish aren’t nearly as careful to minimize the pain for the fish. (I write this as someone who eats fish caught by others.)

Fun fact: Humans have about 86 billion neurons; dogs have about 2 billion; octopuses have about 500 million; mice have about 70 million; guppies have about 4 million; fruit flies have about 100,000; sea slugs have about 10,000.

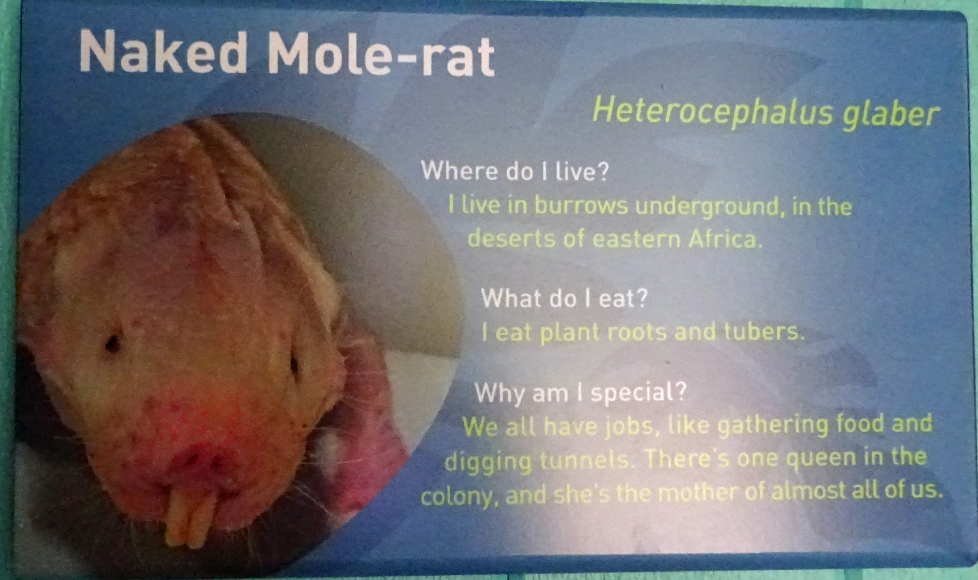

Different animals respond differently to different stimuli. Naked Mole-rats’ can sense pain when pinched or burned, but they don’t react to chemicals such as acids or capsaicin (which makes spicy food painful to humans). Many birds are insensitive to capsaicin, too. We humans aren’t bothered by a chemical in catnip that causes pain to mosquitos, but a scorpion sting that is excruciating to us doesn’t faze a grasshopper mouse. Apparently, nothing is universally painful to all animals.

Figure 07. The lower incisors of Naked Mole-rats can splay apart and close together, to grasp things. More remarkably, these rats can live up to 33 years — extremely long for a rodent!!! They live in elaborate underground tunnels, where carbon dioxide can accumulate; luckily, they can survive up to 18 minutes with no oxygen. Probably more important than their teeth or their underground home is their lifestyle: Like ants or bees, Naked Mole-rats live in cooperative colonies, and they like cuddling together. (If you live in San Diego, you can visit Naked Mole-rats in the Wildlife Explorers Basecamp — aka the Children’s Zoo.)

Though nociception and pain usually occur together, occasionally, they appear separately: Amputees can experience phantom-limb pain in the missing limb, experiencing pain without nociception. Some humans are born indifferent to pain; when their bodies experience nociception, their brains don’t interpret the damage as being painful. In most of us, painkillers can produce the same effect: We’re still aware of an assault on our body, but our brains don’t tell us to suffer from pain. Pain is probably the only sense that we try to avoid and to block out.

Fun fact: Our intestines have taste receptors for sweetness, to know when to release appetite-controlling hormones; our lungs have taste receptors for bitterness, to detect the presence of allergens, triggering an immune response. These sensory receptors don’t route through the brain before taking action; we’re never consciously aware of these processes.

Mammalian nociceptors send localized signals to our brains, prompting us to move away from whatever caused the pain and to protect that area of our bodies from further injury. Octopuses sense and respond to localized pain, too, but squids don’t. When squids sense pain anywhere on their bodies, their entire bodies react. Crustaceans sometimes behave as though they experience pain in response to nociception, but sometimes they don’t; an experienced researcher concludes, “maybe.” Yong — along with many scientists who study pain in animals — says we should err on the side of caution when considering whether an animal feels pain. If it’s possible that it feels pain, we should do our best to avoid causing it.

Insects behave as though they don’t feel pain at all. They keep going even if a limb is crushed, a mate is devouring them, or they’re being parasitized. “If a pain sense is present, it is not having any adaptive influence on behavior” (p. 133). Like all other sensory systems, nociception and perception of pain are costly; it takes energy to produce and maintain the processing power to perceive pain. It may be that such perceptions are too costly for insects to maintain.

Because this blog seems especially long, I’m taking a break here. Future blog posts will discuss more of Yong’s book:

- Part 2 (of 3)

- Chapter 5. So Cool: Heat, 135–155

- Chapter 6. A Rough Sense: Contact and Flow, 156–187

- Chapter 7. The Rippling Ground: Surface Vibrations, 188–209

- Chapter 8. All Ears, Sound, 210–242

- Part 3 (of 3)

- Chapter 9. A Silent World Shouts Back: Echoes, 243–275

- Chapter 10. Living Batteries: Electric Fields, 276–299

- Chapter 11. They Know the Way: Magnetic Fields, 300–319

- Chapter 12. Every Window at Once: Uniting the Senses, 320–334

- Chapter 13. Save the Quiet, Preserve the Dark: Threatened Sensescapes, 335–356

- [back matter], 357–453

- Acknowledgments, 357–359

- Notes, 361–384 (numerical sequence)

- Bibliography, 385–429 (alphabetical)

- Insert Photo Credits, 431–432

- Index, 433–449

- [about the author, 451]

- [about the type, 453]

Copyright, 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch, images and text, except where specific attributions are noted. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment