Figure 01. Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

I read Nobel-winning cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s book several years ago, but I still often think about things he said. I hope you’ll enjoy hearing about what he had to say, too. As Homo sapiens, we’re brilliantly intelligent — smart enough to seek ways to save time and avoid hard work, so we often take mental shortcuts instead of thinking slowly and deliberately. Unfortunately, some of these shortcuts lead us to make foolish decisions and to behave unwisely, based on limited or biased information. Kahneman’s book reveals many of these mental shortcuts, as well as some ways we can think more carefully when the stakes are high for avoiding costly mistakes.

Figure 02. Years ago, Kahneman was interviewed by Ira Flatow, on the NPR (National Public Radio) show, Science Friday. In the interview, Kahneman said that people are mistaken to think that by reading this book they won’t make cognitive errors and will think more clearly. He noted that he wrote the book and still makes many cognitive errors.

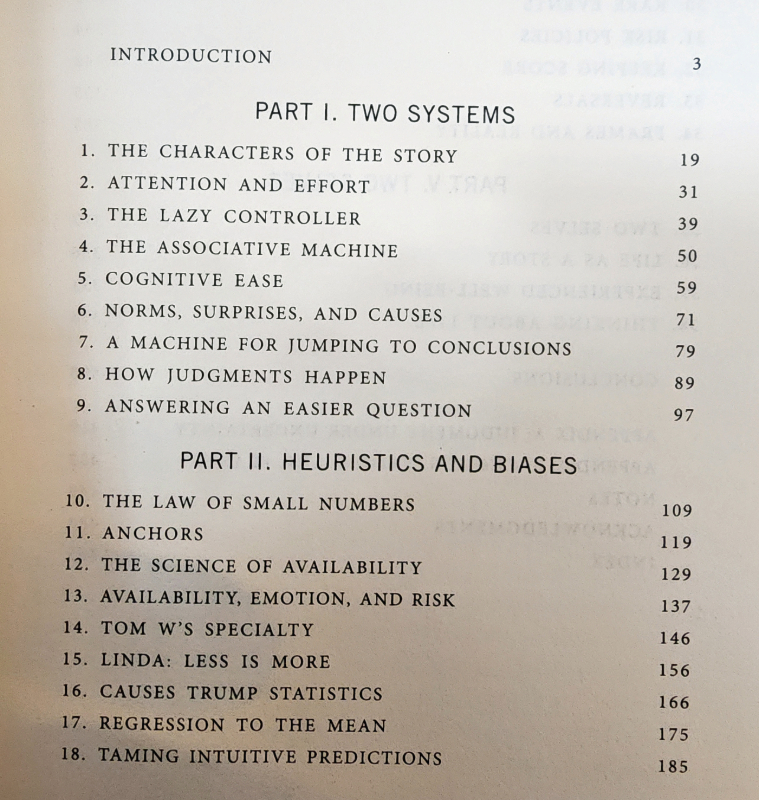

Figure 03. In my first of three blogs about Kahneman’s book, I discussed the introduction and the first two parts of his book: Part I. Two Systems and Part II. Heuristics and Biases. Please see https://bird-brain.org/2025/06/18/thinking-fast-and-slow-by-daniel-kahneman-part-1/)

This second of three blogs about Kahneman’s book discusses Chapters 19–29:

- Part III. Overconfidence, 197–265

- 19. The Illusion of Understanding, 199–208

- 20. The Illusion of Validity, 209–221

- 21. Intuitions Vs. Formulas, 222–233

- 22. Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?, 234–244

- 23. The Outside View, 245–254

- 24. The Engine of Capitalism, 255–265

- Part IV. Choices, 267–374

- 25. Bernoulli’s Errors, 269–277

- 26. Prospect Theory, 278–288

- 27. The Endowment Effect, 289–299

- 28. Bad Events, 300–309

- 29. The Fourfold Pattern, 310–321

My third blog about Kahneman’s book (discussing Chapters 30–38 and the conclusion) will have to wait until after my eyes recover from cataracts surgeries sufficiently to be able to read and write again. I hope that will be soon.

Figure 04. As soon as my eyes have recovered from cataracts surgery well enough to read and write, I’ll be completing my third of three blogs about Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Part III. Overconfidence

19. The Illusion of Understanding, 199–208

In The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb introduced narrative fallacy, describing “how flawed stories [about] the past shape our views of the world and our expectations for the future” (p. 199). We tell ourselves easily memorable stories that are

- simple,

- concrete (not abstract),

- focused on highly salient events that occurred (not on the myriad events that could have happened but didn’t),

- deemphasizing the role of luck, but overemphasizing the importance of talent, intentions, or intelligence — or the lack of these.

We create “flimsy accounts of the past,” which we nonetheless believe are true.

System 2 sees the subtlety, ambiguity, and unpredictability of the real world, but System 1 sees the world as being simple, predictable, understandable, knowable, coherent. Our accounts of events may take advantage of the halo effect (for good or for ill), concluding that unappealing people probably do bad things, and charming, charismatic people do good things. If good things happen, handsome, smart, kind, caring people caused them; if bad things happen, ugly, stupid, mean, uncaring people caused them. Only good people do good things, and bad people do bad things.

These narratives also give the illusion of inevitability. It was inevitable that the good guys would win and the bad guys would lose. It was inevitable that the bad guys would cheat their way to winning and the good guys would lose honorably. In hindsight, what actually happened seems inevitable, and the role of luck or chance seems negligible. Once again, WYSIATI — what you see is all there is. That there could have been any other outcomes seems highly unlikely as we look back on them.

“Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little, when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance. . . . We can know something only if it is both true and knowable” (p. 201).

It is not knowable in advance how events will turn out. We may be able to guess what might happen, or even to make educated guesses based on extensive knowledge, but it is impossible to know in advance what will happen. To make matters worse, “we understand the past less than we believe we do,” so our beliefs about the future, based on our understanding of the past will be even less well founded than we think.

Another aspect of our thinking confounds our understanding. When we experience surprising events — that is, events we did not know in advance would occur — we change our view of how the world works. Pretty soon, we can’t recall how we viewed the world before this surprising event. Often, we can’t even conceive of having viewed the world the way we did before the surprising event. We experience a hindsight bias, in which we feel sure that we anticipated the event that surprised us. We reconstruct our recollection of our prior thinking to believe that we anticipated what happened. “I knew it all along.”

A related bias is outcome bias, in which we consider our appraisal of decisions based on the outcome of the decisions. If a prudent decision turns out badly, we reevaluate it as being a bad decision; if an unwise decision turns out well, we reevaluate it as having been a good decision.

If a physician recommends the best possible treatment, given the available information, and the treatment works, it’s deemed a good decision; if it doesn’t work, however, the physician may be criticized for having made a bad decision. If an investor makes a wildly inappropriate investment, but it turns out well, the investor is considered a boldly courageous genius.

When the consequences of a decision can be devastating, a decision maker may worry that others will be influenced by hindsight bias and outcome bias. To minimize future criticism, the decision maker may choose the least risky option, even if it’s not the optimal choice. CEOs are wise to be wary. Their impact on their companies’ success or failure is greatly exaggerated; they have much less impact than media messages would suggest. The importance of luck is greatly underestimated.

20. The Illusion of Validity, 209–221

We’re much more likely to give credence to a belief if it is held by someone we love and trust than it if is well supported by evidence. If the belief makes a good story, so much the better. Often, even if our predictions, based on our beliefs, fail to come true, we continue to hold these beliefs; our beliefs have an illusion of validity. “Subjective confidence in a judgment is not a reasoned evaluation of the probability that this judgment is correct” (p. 212).

Related to the illusion of validity is the illusion of skill, in which we continue to believe that positive outcomes are based on skill, rather than luck, even when the evidence clearly shows the contrary. For instance, persons who invest in stock believe that stock traders have skill in choosing which stocks to sell and which to buy, despite evidence to the contrary. Some traders do worse and others do better, but “for the large majority of individual investors, . . . doing nothing would have been a better policy than implementing [their ideas for buying and selling stocks] . . . . the most active traders had the poorest results, while the investors who traded the least earned the highest returns” (p. 214). “For a large majority of fund managers, the selection of stocks is more like rolling dice than like playing poker” in terms of the role played by luck, rather than skill. What’s more, traders “appear to be ignorant of their ignorance” (p. 217).

Due to the hindsight bias, we firmly believe that we were able to predict yesterday the events that are happening today, even if there’s evidence to the contrary. Our belief that we understand what happened in the past makes us overconfident about our ability to predict future events. We consistently try to avoid thinking that luck and chance play a huge role in events.

We don’t consider how luck affected historical events either. If our nation was triumphant, we believe that we had brilliant politicians and military leaders, not that we were mostly lucky. Kahneman considers just three events of the twentieth century: the births of Hitler, Stalin, and Mao Zedong. For each of those three births, there was a 50:50 chance the mother could have given birth to a female. There was also a 1 in 8 chance that all three mothers would have given birth to females. How might the twentieth century have been different if each of these newborns had been a female, instead of a male? You may be wondering something similar about one or two contemporary politicians.

Expert political prognosticators made predictions worse than chance when forecasting political events. That is, a novice at darts would have done a better job of predicting the outcomes that occurred. In evaluating their own incorrect predictions, they continued to be unrealistically overconfident in their own ability to predict events. “Experts resisted admitting that they had been wrong, and when they were compelled to admit error, they had a large collection of excuses” (p. 219). They were “dazzled by their own brilliance” (p. 219).

We shouldn’t be too hard on those who make inaccurate predictions because the world is unpredictable. Mistakes in predictions are inevitable. The key, however, is recognizing that an expert’s highly subjective confidence in her or his own predictions is not a good predictor of their accuracy.

21. Intuitions Vs. Formulas, 222–233

In situations involving lots of uncertainty and unpredictability, experts often produce less accurate results than algorithms that apply rules to statistical data. Such situations include medical outcomes, evaluations of credit risk, likelihood of juvenile recidivism, and so on. “There are few circumstances under which it is a good idea to substitute judgment for a formula” (p. 224).

To make matters worse, experts can give different judgments about the same data. These differences may be due to priming effects — situational prompts that affect the expert’s judgment. In interview situations, experts are highly overconfident about their intuitive judgments about the persons interviewed.

Formulas, checklists, and algorithms can provide key life-saving information. For instance, in assessing the health of a newborn, the Apgar Score uses five variables (heart rate, respiration, reflex, muscle tone, color), assessed on a scale of 0, 1, or 2. An infant with a low Apgar Score now receives immediate life-saving intervention, rather than relying on the expert judgment of the medical personnel in the delivery room. Physician Atul Gawande has described many other checklists and lists of rules that have provided invaluable information to surgeons and other experts.

That’s not to say that expert judgment is valueless; it deserves recognition regarding short-term predictions. The accuracy of these judgments, however, diminishes as the predictions become increasingly long term, but the confidence in these judgments doesn’t diminish as much as it should. Kahneman concludes, “do not simply trust intuitive judgment — your own or that of others — but do not dismiss it, either” (p. 232).

22. Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?, 234–244

When using intuition, we have a feeling, a belief that we know something, but we don’t know how we know it. For Kahneman, knowing without knowing “is the norm of mental life” (p. 237). We acquire some intuitions effortlessly, such as the intuition as to when to feel fear. We quickly recognize a situation that somehow signals to us we should feel afraid.

Expert intuitions, however, require considerable effort, practice, and experience. Only through repeated practice and experience do we acquire expert intuition. Greater expert intuition comes from more practice, more study, more experience, even under time pressures, in ambiguous situations, or in situations with limited information. The remarkable thing is that the more expertise a person has, the more the person can recognize a lack of sufficient information to make a judgment. Persons with less expertise are less able to recognize when they lack adequate information for making a judgment. These wannabe-experts ignore what they don’t know and go with WYSIATI — what you see is all there is.

Two basic conditions increase the likelihood that expert intuition is likely to be accurate:

- The environment is regular and stable enough to be predictable

- The expert has had prolonged practice and opportunities to learn about these regularities

These conditions aren’t common in the real world. Without these stable environmental regularities, intuition isn’t likely to be accurate. “Claims for correct intuitions in an unpredictable situation are self-delusional at best, sometimes worse” (p. 241).

Another factor that can improve expert intuition is immediate feedback. If there is a negligible delay between the prediction and the response or outcome, the expert can quickly learn from the experience and modify future predictions. If there is any lag, let alone a long delay, this learning is less likely. Of course, the response or outcome must be known to the expert and must accurately reflect the situation. For instance, an anesthesiologist will get immediate feedback regarding how well the anesthesia is working. Outcomes of a radiologist’s diagnosis will be delayed, may not be known to the radiologist, and may also be affected by other intervening factors (e.g., exposure to carcinogens following the X-ray). The radiologist’s subjective confidence in the diagnosis won’t truly reflect its accuracy.

23. The Outside View, 245–254

Often, when we take on a long-term project, we use a planning fallacy, in which we grossly underestimate how much time and effort will be involved to complete the project. For instance, suppose that a blogger had planned to complete her blogs about a book prior to her cataracts surgery and assumed that she had plenty of time to do so; if she didn’t complete the blogs prior to the surgery, she would have fallen prey to the planning fallacy.

Once we’re involved in the project, having invested much more time and effort than we had anticipated, we may show irrational perseverance. Refusing to accept that the project isn’t worth the time and effort, we continue obstinately for much longer than we should, based on the sunk-cost fallacy. We believe that we have already spent so much time and effort on the project, we shouldn’t abandon it — so we then expend even more time and effort for even smaller hope of recouping our losses.

In estimating the time and effort needed, we take the inside view, focusing solely on our own experiences and circumstances. We don’t anticipate how chance events may affect the amount of time we have available or the amount of effort we can dedicate to the project. “The likelihood that something will go wrong in a big project is high” (p. 248, emphasis in original), but the likelihood that we will anticipate it and consider it in our planning is extremely low.

If, instead, we take an outside view, we will investigate how much time and effort was needed to complete similar projects with similar complexity and extensiveness. If we can find comparable projects and consider how much time and effort (and how many resources and personnel) were available for its completion, we can get a more realistic idea of how much it will take to complete our own project.

Without considering the outside view, our own plans amount to the best-case scenario, in which all elements of luck and happenstance go our way. By considering the outside view, we can develop a more realistic — and less fallacious — plan.

The planning fallacy also applies to professionals, such as building contractors. “In 2002, a survey of American homeowners who had remodeled their kitchens found that, on average, they had expected the job to cost $18,658; in fact, they ended up paying an average of $38,769” (p. 250). The building contractors also point to a compounding factor: To get a project approved (e.g., by a client, a company, or a government agency), it’s better to underestimate the costs and the time needed.

“Organizations face the challenge of controlling the tendency of executives competing for resources to present overly optimistic plans” (p. 252). This optimistic bias further compounds the problem. Once the project is underway, additional costs and time rarely lead to abandonment of the project. That is, participants fall prey to the sunk-cost fallacy.

Politicians are subject to both the planning fallacy and the optimistic bias when starting wars.

Planning experts refer to the outside view as “reference class forecasting,” using large databases of information on similar projects, their plans, and their outcomes. The key is to find a suitable “reference class” to make the information relevant. Projects that aren’t truly similar won’t help much in figuring out how to plan.

Kahneman ended the chapter by saying he now habitually looks for the outside view before taking on a new project, but he admitted that it doesn’t feel natural to do so.

24. The Engine of Capitalism, 255–265

The planning fallacy is one of many ways in which we demonstrate “a pervasive optimistic bias” (p. 255). Not only do we overestimate our own abilities and our ability to achieve our goals, but we also overestimate our own ability to predict the future, which leads to overconfidence. “The optimistic bias may well be the most significant of the cognitive biases” (p. 255). Apparently, many of us have this bias: “90% of drivers believe that they are better than average” (p. 259).

Optimism has many virtues: Optimists are usually cheerful and happy, likeable, resilient in adapting to hardships and failures, physically healthier, and more likely to live long. They’re less likely to be depressed and more likely to have strong immune systems, and also more likely to take care of their physical health. That’s assuming that the optimists still manage to keep some grasp of reality. They have an optimistic bias, but they’re not completely delusional.

We’re more likely to be overly optimistic in our self-assessments on things we do moderately well (e.g., driving), rating ourselves as being above average. For tasks we find difficult, however, we more readily acknowledge ourselves to be below average — such as being able to start conversations with strangers.

Optimists are also more likely to be risk takers. They’re more likely to underestimate the chances of failure and overestimate the chances of success. Similarly, they underestimate the role of luck and overestimate their own role in their good fortune. Optimists are more likely to persist in spite of obstacles — which can be a good thing when the chances of success are at least 50:50. But which can be costly if the likelihood of failure is high.

Even if we don’t have a strong optimism bias, we are subject to other cognitive biases. We focus on what we know, and we ignore what we don’t know, developing a false confidence in our knowledge. We focus on how our own skills can help us to achieve our goals and neglect to consider the importance of luck. We fall prey to the illusion of control, believing that we have more control over events than is realistic. We engage in the planning fallacy, focusing more on our intentions and abilities, rather than on how other factors may affect outcomes.

We also think about our own skills, motivations, and abilities, but we don’t think that others may have comparable skills, motivations, and abilities. For instance, we think about how well we would do at launching our own business in our area of expertise, but we don’t think about the 65% of new small businesses that fail within the first five years. Were all those failures the result of ineptitude, lack of skill, or lack of motivation?

When thousands of chief financial officers were asked to forecast the returns of the Standard & Poors index, “the correlation between their estimates and the true value was slightly less than zero!” (p. 261). Nonetheless, these “CFOs were grossly overconfident about their ability to forecast the market” (p. 262).

Physicians were similarly overconfident about their diagnoses; in postmortem examinations, 40% of the diagnoses were wrong. To be fair, many of these diagnoses were unpredictable. The physicians made a best guess, and 60% of the time, they guessed correctly. Because the stakes are so high for the patients, however, the physician may feel pressured to appear more confident of the diagnosis than is truly realistic.

Kahneman observed that a bit of overconfident optimistic bias may be essential to scientists, who face frequent failures and rare successes — repeatedly.

One way to prevent having optimistic bias lead you (or your organization) to make a big mistake in starting a new project: Conduct a premortem. Gather all those who are participating in the decision. Ask them to think about this: Assume that you went ahead with the project, and a year later, it was an unmitigated disaster. Write a brief history of how that disaster occurred. This alternative perspective will at least give everyone a chance to consider alternatives other than the most optimistic best-case scenario.

Part IV. Choices

25. Bernoulli’s Errors, 269–277

“To a psychologist, it is self-evident that people are neither fully rational nor completely selfish” (p. 269).

When making decisions, even simple, certain decisions may have unexpected outcomes. For instance, if buying a condominium, you may be able to judge whether the market price has gone up or down and will be likely to go up or down in the near future, but you may not be able to predict “that your neighbor’s son will soon take up the tuba” (p. 270). Unlike economists, psychologists Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky don’t expect humans to make entirely rational decisions.

When offered a risky option with a bigger reward or a certain option with a smaller reward, most people choose the certain option. “Most people dislike risk,” so they’re willing to pay “a premium to avoid the uncertainty.” Put in a different way, “people’s choices are based not on dollar values, but on the psychological values of outcomes” (p. 273). Insurance companies benefit from this outlook. Most of us are willing to pay a premium to avoid a catastrophic loss.

Kahneman disputed an economic theory in this chapter and went on to say, “Once you have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in your thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws” (p. 277). If you observe something that doesn’t fit your theory, you’re likely either to ignore it or to assume that there’s a good explanation for why it doesn’t fit.

26. Prospect Theory, 278–288

We think of our wealth more in terms of changes in wealth, than as states of wealth. We also think of gains very differently than losses. Kahneman gives these two examples:

Problem 1: Which would you choose? Gain $900 as a sure thing, or have a 90% chance of gaining $1,000

Problem 2: Which would you choose? Lose $900 as a sure thing, or have a 90% chance of losing $1,000

If you’re like most people, when you think in terms of gains (Problem 1), you avoid risk and stick with the sure thing. We subjectively value having $900 in our pocket more than a possibility of having $1,000.

On the other hand, you probably view losses very differently (Problem 2). If you’re like most people, a certain loss is highly aversive, so you’ll probably take a chance on losing $1,000, in order to keep from having a certain loss. This is an example of loss aversion.

When all of our options are bad, we’re much more likely to take a risk than when all of our options are good. Kahneman gives another set of examples:

Problem 3: You’ve been given $1,000. Which would you choose? Be given $500 more as a sure thing, or take a 50% chance of gaining an additional $1,000

Problem 4: You’ve been give $2,000. Which would you choose? Lose $500 for sure, or take a 50% chance of losing $1,000

As you may have guessed, most people chose the sure gain in Problem 3, but they chose the risky option in Problem 4. For most of us, we dislike losing much more than we like winning. Also, we typically have a reference point for making judgments. If the outcomes are better than the reference point we expected, we see them as gains; if worse than the reference point, we see them as losses. The reference point also affects how much of a difference seems important. If we add $100 to $10,000, it doesn’t seem that important, but if we add $100 to $10, it’s a big deal.

Our aversion to loss may be deeply rooted in our ancestry, in that we perceive losses as threats, and threats alert us to pay attention and take action far more than perceived gains do.

Kahneman also showed how economists’ “prospect theory” fails to take account of human cognitive processes, especially risk preferences in regard to gains versus losses.

27. The Endowment Effect, 289–299

When we consider a change, we view it relative to our current situation, or reference point. If we’re considering a move to a new job, we consider its salary and benefits relative to our current salary and benefits. Loss aversion also plays a role here. We’re more sensitive to potential losses of salary and benefits, and we weigh them more heavily than potential gains. Often, loss aversion leads us to accept the status quo, even if it’s less than ideal.

Loss aversion also affects our willingness to sell something we own. Because of the endowment effect, simply owning something increases its value to us. By virtue of our owning the item, it’s more valuable to us than it was before we bought it. The potential pain of losing the item is greater than the pleasure we felt upon gaining it.

Professional sellers and traders, however, don’t show the endowment effect. They seek the best price for the market conditions, regardless of whether they’re selling or buying.

28. Bad Events, 300–309

Animal brains (like ours!) are primed to prioritize bad news. Doing so offers an adaptive advantage: The more quickly we sense and respond to a predator or other threat, the more likely we are to survive. Brain studies confirm that our brains activate immediately — without conscious intervention from the visual cortex — when we see a threat. As Kahneman says, “threats are privileged above opportunities” (p. 300).

In our modern society, physical threats are few, but our brains are still primed to respond to perceived threats of whatever kind. In addition, “bad information is processed more thoroughly than good” (p. 302). An expert in marital relationships noted that in a good stable marriage, good interactions must outnumber bad ones by at least 5:1. Otherwise, our tendency to overthink bad interactions may cause us to outweigh them over good ones.

Our tendency to weigh losses over gains makes any negotiations challenging. If you and I are negotiating terms, I will deeply feel any concessions I make to you as losses, but I will not weigh as heavily the gains you offer to me. You, however, will take the opposite view, weighing my offers of gains less heavily than my requests for concessions. That is, your losses cause you more pain than they give me pleasure, and vice versa. Skilled negotiators use reciprocity to ensure that a painful loss by one side will be balanced by a painful loss on the other side. Gains will be likewise reciprocal.

Back to animals: They, too, care more about losses than gains. When an intruder tries to take another animal’s territory, the territory holder almost always triumphs because the holder cares much more deeply about not losing it than the intruder cares about gaining it. (I remember hearing a naturalist say that when a coyote is chasing a rabbit, the coyote is more likely to slow down or to give up because to the coyote, the chase is about trying to gain a meal, but to the rabbit, the chase is about trying not to lose its life.)

Reform efforts are typically especially hard fought when current stakeholders feel that they will be losing if the reform is implemented. Often, the only way to move forward with the reform is to include a grandfather clause allowing current stakeholders to continue the status quo, so they won’t lose during the reform process.

This aversion to loss helps to maintain communities, neighborhoods, families, workplaces, marriages. The potential gains of making big changes may not be enough to outweigh the perceived losses.

Perceived losses also affect perceived fairness. Suppose that a government imposes a 25% tariff on imported goods. Some companies who rely on foreign imports boost their prices by 25%. If these companies didn’t do so, they would suffer great financial losses. Most buyers would balk, but if they could afford to do so, they would pay the higher price. Other companies, which don’t import any goods, also boost their prices by 25%. Buyers would probably refuse to pay these higher prices because these companies wouldn’t suffer any loss if they didn’t raise their prices.

29. The Fourfold Pattern, 310–321

We weigh different probabilities differently. The difference between a 0% probability and a 5% probability is far more significant to us than the difference between a 5% probability and a 10% probability. This difference is known as the possibility effect — the difference between something being highly improbable and being completely impossible. We exaggerate the importance of the highly improbable event because it has become possible. When applied to a risk of losing, we’re often willing to pay excessively to be certain of avoiding a loss. (How much would you be willing to pay to reduce the chance of your child getting a devastating disease from 5% to 0%?) “Improbable outcomes are overweighted” (p. 312). States that run lotteries take advantage of the possibility effect.

Similarly, the difference between a 95% probability and a 100% probability is far more significant to us than the difference between a 90% probability and a 95% probability. This difference is the certainty effect — the difference between something being highly probable and being absolutely certain. We undervalue the importance of the highly probable event because it is not certain. Civil litigators take advantage of the certainty effect, offering settlements dramatically less than the plaintiff might have received by having a court judge the issue.

The weights we give to outcomes are not the same as the probabilities of those outcomes. We undervalue nearly certain outcomes in favor of certain ones. Intermediate probabilities are also subject to distortions in valuation, but less so than the extremes of probability. Most of us spend little time worrying about the likelihood of a tsunami or fantasizing about a million-dollar gift from a stranger. Some of us, however, do worry about highly improbable events; only a 0% chance would eliminate the worry.

In the fourfold problem, the certainty effect comes into play differently for gains than for losses in a hypothetical legal settlement:

If a person has a 100% chance of gaining $9,500 or a 95% chance of gaining $10,000 — risk aversion comes into play, and the person accepts the smaller but certain settlement

If a person has a 100% chance of losing $9,500 or a 95% chance of losing $10,000 — risk seeking comes into play, and the person rejects the smaller but certain settlement loss

If a person has a 5% chance of winning $10,000, the person will take the risk

If a person has a 5% chance of losing $10,000, the person will avoid the risk

To put it another way, when the difference is between high probability and certainty, we seek certain gains but gamble to avoid losses. When the difference is between low probability and certainty, we gamble for gains and seek certainty to avoid losses.

Perversely, plaintiffs with strong cases, who seem to be winning in court, are more likely to be risk averse than plaintiffs with weak cases, who seem to be losing in court. When city governments must decide whether to settle frivolous lawsuits, they must calculate the likelihood of a few big losses versus many small losses. Often, they choose to settle most cases, which may ultimately cost them more money.

Figure 05. In this blog, my second of three about Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow, I discussed these chapters.

My third of three blogs about Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow will be forthcoming, after both of my eyes have recovered from cataract surgery well enough to read and write again.

Copyright © 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment