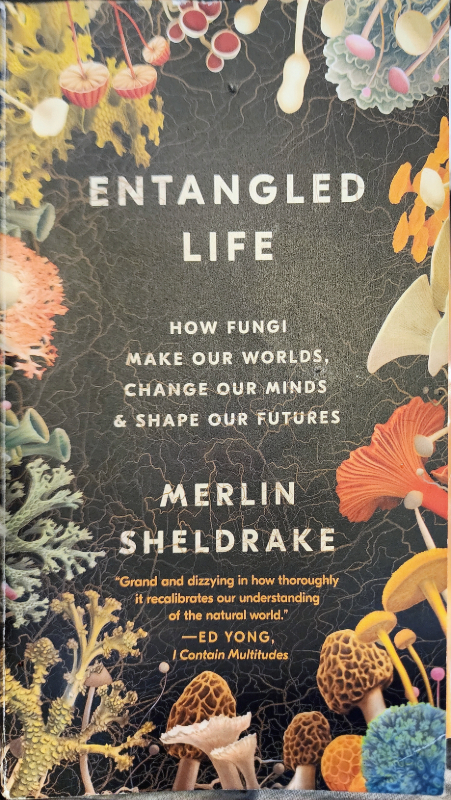

Figure 01. Sheldrake, Merlin. (2020). Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures. New York: Random House.

I’m ashamed to admit that when I was a schoolchild in the 1950s, I believed that fungi were a second-class kind of plant, one that couldn’t photosynthesize and did little else than sprout mushrooms (or “toadstools”) after rain, or perhaps add texture to tuna-noodle casserole.

What’s more shameful, I didn’t know that fungi were a whole separate kingdom of life on Earth until far too recently to admit. I hope that contemporary schoolchildren are far less ignorant than I was.

Contents

- Prologue ix–x

- Introduction: What Is It Like to Be a Fungus? 3–23

- 1. A Lure 25–44

- 2. Living Labyrinths 45–69

- 3. The Intimacy of Strangers 70–93

- 4. Mycelial Minds 94–122

- 5. Before Roots 123–148

- 6. Wood Wide Webs 149–174

- 7. Radical Mycology 175–201

- 8. Making Sense of Fungi 202–222

- Epilogue: This Compost 223–225

- Back matter 227–353

Prologue ix–x

Sheldrake described his adventure tracing tree roots into their fungal networks in a tropical setting.

Introduction: What Is It Like to Be a Fungus? 3–23

“Fungi are everywhere . . . inside you and around you. They sustain you and all that you depend on. . . . fungi are changing the way life happens, as they have done for more than a billion years. They are eating rock, making soil, digesting pollutants, nourishing and killing plants, surviving in space, inducing visions, producing food, making medicines, manipulating animal behavior, and influencing the composition of the Earth’s atmosphere” (p. 3).

The diversity of fungi can be breathtaking, from microscopic yeasts to networks of Armillaria, “among the largest organisms in the world. . . . [weighing] hundreds of tons, . . . across ten square kilometers, . . . somewhere between [2,000 and 8,000] years old” (pp. 3–4). In our Earth’s history, fungi existed long before plants, and they made plant life possible. Even today, 90% of plant species depend on mycorrhizal fungi — fungi that intertwine with their roots, exchanging needed soil nutrients for the plants’ photosynthesized sugars.

Much of Earth’s land surfaces are colonized by lichen, an organism comprising the union of at least one fungus and at least one alga or bacterium, often more than one. In many ecosystems, fungal tissue holds soil together, preventing it from eroding or being carried away by water. Fungi are masters of metabolism, able to eat rocks, crude oil, polyurethane plastics, TNT explosives, and even — toughest of all — lignin, the component of wood that enables trees to stand hundreds of feet tall, holding up heavy canopies of leaves and branches. Fungi can even metabolize radiation and use it as a source of energy.

In our popular imaginations, when we think of fungi, we think of mushrooms, which are the “fruiting bodies” of most fungi, where spores are produced. Spores are the reproductive beginnings of new fungi, and they leave the fruiting bodies to disperse by way of wind, rain, ants, squirrels, and so on.

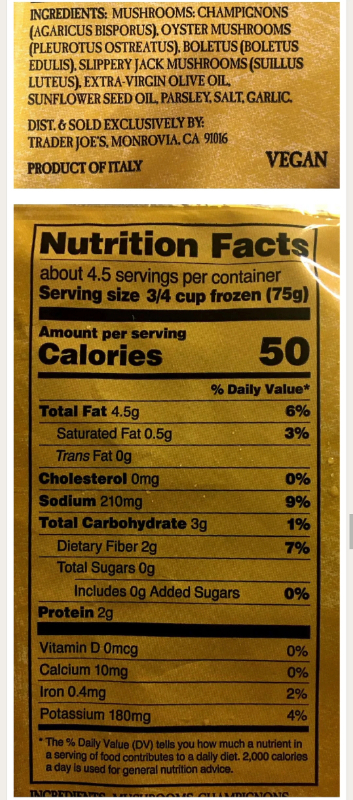

Figure 02. If you’re like me, the fungi you most often think about are mushrooms, the fruiting bodies of some species of mushrooms. This mushroom blend from Trader Joe’s includes Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Boletus edulis, and Suillus luteus. To be honest, I had never paid attention to those species names before writing up my notes for this blog.

Some fungi, such as the yeasts that enable bread to rise or that ferment sugars into alcohols, exist as single cells, which multiply by budding into two cells, which multiply into four cells, and so on. Most fungi, however, form hyphae, infinitesimally fine tubes that form networks, which tangle and branch to form the fungi’s mycelium. That is, hyphae work together to make the mycelium, as well as the mushroom fruiting bodies, “the felting together of hyphal strands.” These fruiting bodies are also highly diverse, from highly prized truffles to the mushrooms most of us eat to highly toxic toadstools to any number of others.

Figure 03. Sheldrake chose to highlight Coprinus comatus mushrooms, commonly known as shaggy ink cap mushrooms, having the book’s illustrator, Collin Elder, use its ink for all of the drawings in the book. If you leave this mushroom in a jar, it will “deliquesce into a pitch-blank ink over the course of a few days.” (To deliquesce is to dissolve from a solid into a liquid. I had to look it up.) This image was taken by Kuzey Gunesli, posted to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mycoremediation, and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work, to remix or to adapt the work, as long as you provide attribution.

Though all animal life depends on fungi, at least indirectly (through plants), some animals directly do so, such as leaf-cutter ants, which cultivate fungi, feeding their farmed fungi bits of leaves that they’ve cut.

Fungi are not always the hero of the story for humans. Fungi cause blights on entire forests, wipe out crops, mildew prized possessions, cause pricey food to get moldy, drive species of amphibians and other creatures to extinction, cause fungal superbugs resistant to treatment, and so on.

On the other hand, fungi sometimes are our heroes and have been documented to have done so for Neanderthals and for Homo sapiens up to the present. It turns out that while some fungi have amicable relationships with some bacteria — even symbiotic ones, at times — some fungi do battle with bacteria, such as the life-saving fungus that has provided us with penicillin since the early 20th century. Since the discovery of penicillin, researchers have discovered numerous other fungal-based medications, such as cyclosporine (immunosuppressant used in organ transplants), numerous statins (for lowering cholesterol), antiviral drugs, anticancer drugs, and vaccines.

Mycologists talk of

- mycoremediation, in which fungi are used to break down pollutants into less toxic forms

- mycofiltration, in which fungi filter toxins and heavy metals from water to purify it

- mycofabrication, in which fungi are used to make biodegradable alternatives to plastics or to make vegan alternatives to animal products, such as leathers

There are between 2.2 and 3.8 million species of fungi on Earth, and we have probably identified and described only 6% of them so far. The future possibilities of fungi research seem limitless.

To Sheldrake, some of the most intriguing aspects of fungi are their symbiotic relationships, such as the symbiotic relationships with plants that make life on Earth possible for the humans and other animals alive today. “The relationships between plants and mycorrhizal fungi are key to understanding how ecosystems work” (p. 12). The relationships are complex — often multiple fungi interact with an individual plant, and an individual fungus may interact with multiple plants. Plants and fungi also form complex social networks, which can be called the “wood wide web” in forests.

We humans take an anthropocentric view of the world, ignoring the amazing capabilities of plants, fungi, and microbes. For instance, only recently have scientists noted the capabilities of a related life form, slime molds (amoebae, not true molds), which readily solve complex spatial problems, such as navigating through a maze to find a food source. Only in recent years have we also become aware of our own microbiome, all the microbial life that lives in and on our human bodies: About 40 “trillion microbes that live in and on our bodies allow us to digest food and produce key minerals that nourish us” (p. 17).

Sheldrake suggests that we think of ourselves as ecosystems. Also, each microbe interacts with other microbes. For instance, bacteria contain viruses, and those viruses may even contain smaller viruses. “Biology — the study of living organisms — [has] transformed into ecology — the study of the relationships between living organisms” (emphasis added, p. 17).

Figure 04. In his introduction, Sheldrake described his experience taking LSD (a derivative of a fungus) in a clinical setting.

1. A Lure 25–44

Sheldrake explores the mysterious and exclusive world of hunting for truffles, coveted and prized fruiting bodies of particular fungi. He also reveals insights about the olfactory senses of humans and other animals, via their olfactory epithelium, which sends odor signals to our brains. Regarding fungi, he says, “their entire surface behaves like an olfactory epithelium. A mycelial network is one large chemically sensitive membrane. . . . Fungi spend their lives bathed in a rich field of chemical information” (p. 28).

Male orchid bees collect numerous scents and concoct perfumes to attract females.

Truffles’ scent emerges “out of the relationships the truffle maintains with its community of microbes and the soil and climate it lives within — its terroir” (emphasis added, p. 31). It’s energetically costly to produce these aromas; truffles evolved their scents to communicate to animals that they’re ready to be eaten. “To attract an animal the aroma has to be curious, and delicious—yes. But most of all it has to be penetrating and strong” (p. 35). In fact, however, truffle-producing fungi communicate in myriad other ways, with their truffles actually being among the least sophisticated means.

Fungal hyphae have two main ways of moving to create a mycelial network:

- Branch

- Fuse

They need to branch in order to spread into complex networks, but then they need to attract other hyphae. Attracting (a process called “homing”) and then fusing with other hyphae “is the linking stitch that makes mycelium mycelium, the most basic networking act” (p. 36). It’s likely that pheromones are involved in the attraction.

Fungal mycelium comprise an intricate network of hyphae, which grow in multiple directions, simultaneously. To see various views of fungal mycelium, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mycelium

When hyphae are about to fuse, they need to be able to tell whether the other hyphae are (a) themselves (e.g., splitting around an obstacle then reuniting), (b) either the same species or an otherwise compatible species, or (c) an incompatible species. When hyphae fuse with a separate but genetically and sexually compatible species, they have fungal sex. One of the fusing partners gives the other some genetic material (the “paternal” partner), and that partner (the “maternal” partner) adds its own genetic material and creates the flesh that becomes fruiting bodies (e.g., truffles) and spores.

Typically, fungi need to interact with plants to facilitate fungal sex, leading to fruiting bodies and spores. These complicated interrelationships and other intricacies of their sex lives are part of why it hasn’t yet been possible to domesticate (farm) truffles or several other mycorrhizal fungi (e.g., chanterelle, porcini, and matsutake mushrooms). To cultivate fungi, “you have to understand the quirks and needs not only of the fungi — with their idiosyncratic reproductive systems — but also of the trees and bacteria they live with” (p. 39). Truffles (and, presumably many other fungi) require trees in a healthy ecosystem in order to thrive.

Figure 05. The mushrooms in this medley have been cultivated: Agaricus bisporus mushrooms (aka portobello, button, cremini mushrooms), Pleurotus (oyster), Boletus edulis (porcino), and Suillus luteus (slippery jack, aka sticky bun).

Fungi definitely have a sinister side, too. Some fungi not only devour living nematode worms, but they also seek them out and trap them, using adhesive nets or branches, nooses, paralyzing chemicals, spores that bind to them, or harpoons. Surprisingly, even within a given species, a fungus may use different weapons or tactics to trap their nematode prey.

Though fungi don’t have brains, they do make decisions, and they constantly adapt to an ever-changing environment. “Fungi actively sense and interpret their worlds” (p. 44).

2. Living Labyrinths 45–69

“When faced with a forked path, fungal hyphae don’t have to choose one or the other. They can branch and take both routes” (p. 45). When an obstacle obstructs their path, they branch and go around it. If the obstruction is small, they may fuse again after passing the obstacle.

Experiments involving fungi have shown they have similar spatial problem-solving abilities to those of slime molds. One way to view their actions is as swarms, like swarms of ants or murmurations of starlings. In one view, mycelium “is a single interconnected entity”; but if viewed from each hyphal tip, each mycelium “is a multitude” (p. 47).

The spatial problem-solving skills of fungi and slime molds have been used to figure out human problems, such as fire-evacuation routes in buildings. Mycelium constantly evaluate their environment to create the best network: A dense network has multiple nodes and a high capacity for transport, but it can’t easily traverse long distances and spread across large areas. A sparse network can cover a lot of area but it’s vulnerable to injury, has fewer nodes, and can’t transport efficiently.

Figure 06. I did not appreciate the industriousness of the mold forming on my blackberries when I first got them home from the store. In my compost bin, it is traversing from the blackberries to the other organic matter there.

One strategy mycelium use is to investigate an area using “exploratory mode,” proliferating with multiple hyphal links in multiple directions simultaneously. If a few of the hyphae stumble across food, the mycelium strengthens those links to the food; if some of the hyphae encounter problems or simply don’t find food, the mycelium prunes back the hyphae leading in that direction. If we could view it from above, we might see it migrating toward a food source and away from a resourceless area, but even then, the mycelium continues to explore with at least some hyphae in all directions. That is, there’s no central command and control: “Mycelial coordination takes place both everywhere at once and nowhere in particular” (p. 50).

Benjamin Franklin proposed using bioluminescent fungi to illuminate the gauges of a newly invented submarine.

The mycelium’s hyphal tips grow by lengthening, adding “new naterial as they advance. Small bladders filled with cellular building materials arrive at the tip from within and fuse with it at a rate of [600/second]” (p. 53). Some hyphae species grow so quickly that you can literally watch the growth in real time. Sheldrake urges us to think of mycelium not as a thing but as a process.

When hyphae felt together to make mushrooms, they stop lengthening and instead “rapidly inflate with water, which they absorb from their surroundings” (p. 53). The abundance of water available after a rain prompts the seemingly explosive growth of mushrooms. Not all hyphae structures are mushrooms, however. Some species of fungus produce other kinds of structures, such as “hollow cables of hyphae known as ‘cords’ or ‘rhizomorphs,’” large pipes formed from numerous smaller tubes (p. 55). These larger pipes can readily transport fluids rapidly across large distances.

Most species of fungi sense and respond to myriad stimuli simultaneously: “light (its direction, intensity, and color), temperature, moisture, nutrients, toxins, and electrical fields” (p. 58). Fungi even have “opsins, the light-sensitive pigments present in the rods and cones of animal eyes” (p. 58). Hyphae can detect surface textures, too. When hyphae felt into mushrooms, they’re highly responsive to gravity. And, as mentioned previously, fungi are exquisitely sensitive to chemicals, allowing them to send and receive chemical messages to themselves and to other organisms.

Figure 07. Mycelial hyphae are only one cell thick, 2–20 micrometers in diameter, about 1/5th the diameter of a human hair. Given this basic structure, mycelial networks vary widely: some thick, some thin; some picky about what they eat, some not so much; some form closely around a single food source, others range widely; some are delicate, others can exert enough pressure to penetrate Kevlar (used for making vests that bullets can’t penetrate!).

Beatrix Potter, author and illustrator of children’s books, was a naturalist who specialized in mycology, and created beautifully accurate drawings of fungi. The sexism of her day prevented her illustrations from being published.

Charles Darwin and his son Francis wrote The Power of Movement in Plants (1880), in which they asserted that the growing tips of plants — of both roots and shoots — are where the plant integrates information to figure out the best way to grow. According to Sheldrake, the same is true of hyphal tips; they’re the place where the mycelium integrates information to figure out where and how to “grow, change direction, branch, and fuse. . . . A given mycelial network might have anywhere between hundreds and billions of hyphal tips, all integrating and processing information on a massively parallel basis” (p. 59).

“The Latin root of the word intelligence means ‘to choose between.’ Many types of brainless organisms — plants, fungi, and slime molds included — respond to their environments in flexible ways, solve problems, and make decisions between alternative courses of action. . . . [Perhaps] intelligent behaviors can arise without brains” (p. 66, emphasis in original). Sheldrake also gives the example of octopuses, which distribute their intelligence throughout their bodies, rather than storing it in a unitary brain.

Fossils dating 2.4 billion years ago reveal a fungal mycelial network closely resembling the networks alive today. “Mycelium has persisted for more than half of the four billion years of life’s history” on Earth (p. 67).

“In 1845, Alexander von Humboldt observed that ‘Each step that we make in the more intimate knowledge of nature leads us to the entrance of new labyrinths’” (p. 69).

Figure 08. Researchers don’t yet know how mycelium manage to communicate information throughout the network so quickly. Could it be through changes in pressure or flow? Could it be electrical conduction? Lots of experimental evidence supports the use of some kind of electrical signaling within mycelium. Some researchers even hold out the prospect of “fungal computers” being used to monitor features of an ecosystem.

3. The Intimacy of Strangers 70–93

Ernst Haeckel coined the word ecology in 1866, inspired by Alexander von Humboldt’s view that nature is “a system of active forces,” with no organism understandable in isolation (p. 71).

In forming lichen, the mycobiont (the fungal partner) grabs nutrients from rocks and other surfaces, and it offers physical protection for its algal partner. The photobiont (usually the algal partner, but perhaps instead a photosynthetic bacterial partner) harvests sunlight and carbon dioxide to produce sugary energy for the mycobiont. By uniting, they can make a living in places where neither one could survive alone. Scientists were slow to accept the symbiotic (mutually beneficial) relationship of the lichen symbiont, either ignoring it altogether or contriving it as a parasitic relationship.

To see a diagram of the structure of one kind of lichen, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lichen#Internal_structure, which reveals how the mycobiont (fungal) and the photobiont (algal or bacterial) partners interweave. Several species of lichen have been aboard the ISS (International Space Station) for up to 1½ years. Quite a few survived the experience.

“Lichens encrust as much as [8%] of the planet’s surface, an area larger than that covered by tropical rainforests” (p. 74). Highly variable, lichens cling to almost any surface imaginable, are adorned in brilliant coloration or camouflage, and look like shrubs, antlers, or smudged stains. Some live on insects, while others blow from place to place. Their appearance has been described as “crustose (crusty), foliose (leafy), squamulose (scaly), leprose (dusty), fruticose (branched)” (p. 74, emphasis added).

When lichens mine the nutrients in rocks through weathering, they use the force of their own growth to physically, mechanically break up the rock. Next, they use “an arsenal of powerful acids and mineral-binding compounds to dissolve and digest the rock” (p. 75).

In 2001, Joshua Lederberg coined the term microbiome. Since then, researchers have become increasingly aware of its interplay with all of Earth’s organisms.

Biologist Joshua Lederberg discovered that bacteria could trade genes with each other “horizontally,” with associates, not just “vertically,” with parents and offspring. In this way, genes — and their traits — can infect neighboring bacteria. Genes that have evolved in separate bacteria for millions of years can transfer from one bacterium to another. In fact, “for bacteria, horizontal gene transfer is the norm” (p. 78).

Life on earth “is divided into three domains. Bacteria make up one. Archaea — single-celled microbes that resemble bacteria but which build their membranes differently—make up another. Eukarya make up the third” (p. 80). All multicellular organisms are eukaryotes.

“In 1967, the visionary American biologist Lynn Margulis . . . argued that . . . . Eukaryotes arose when a single-celled organism engulfed a bacterium, which continued to live symbiotically inside it” (p. 80). Out of these symbiotic relationships, eukaryotes developed

- mitochondria (the energy powerhouses of our cells)

- and chloroplasts (the photosynthesizing structures in plants, believed to have arisen when an early eukaryote engulfed a photosynthetic bacterium).

All multicellular life forms involve this “intimacy of strangers,” which can also be called endosymbiosis (p. 81). In this view, plants “emerged from the combination of organisms that could photosynthesize with organisms that couldn’t” (p. 82).

“Lichens are emergent phenomena, entirely more than the sum of their parts. . . . Lichens are small biospheres that include both photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic organisms” (p. 83). Lichens can also go into a dormant state, where their tissues can’t be destroyed by dehydration, freezing, thawing, heating, then when conditions become favorable, they revive. In addition, “Lichens . . . produce more than a thousand chemicals that are not found in any other life-form, some of which act as sunscreens” (p. 84). Sheldrake calls lichens extremophiles, able to survive in environments deadly to most other organisms. In fact, once lichens are introduced into these inhospitable environments, they make those places more habitable. To say lichens are long-lived is an understatement; the record-holder for a lichen is more than 9,000 years (in Swedish Lapland).

Lichens have evolved independently at least 9 times, and possibly more. “It turns out that fungi and algae come together at the slightest provocation” (p. 86). On the other hand, the two do have to be compatible; not all fungi and algae are. Each symbiont must be able to do something that the partner symbiont can’t do alone. This may be why lichens are extremophiles. In seemingly unlivable conditions, symbiosis may be the only way for either organism to survive.

Initially, researchers believed that each lichen was created by one fungus and one alga or bacterium. More recently, researchers have realized that multiple organisms may be entwined in this symbiotic relationship: multiple fungi, multiple algae, and even multiple bacteria may be interrelated in a single lichen. Each lichen must have at least one fungus and one alga or bacterium, but numerous other partners may be interrelating. This new view considers lichens to be “dynamic systems rather than a catalogue of interacting components” (p. 90, emphasis in original).

What is true for lichens is true for us, in that “life is nested biomes all the way down” (p. 91). We may be viewed as “holobionts . . . an assemblage of different organisms that behaves as a unit. . . . Holobionts are . . . more than the sums of their parts” (p. 92, emphasis added).

4. Mycelial Minds 94–122

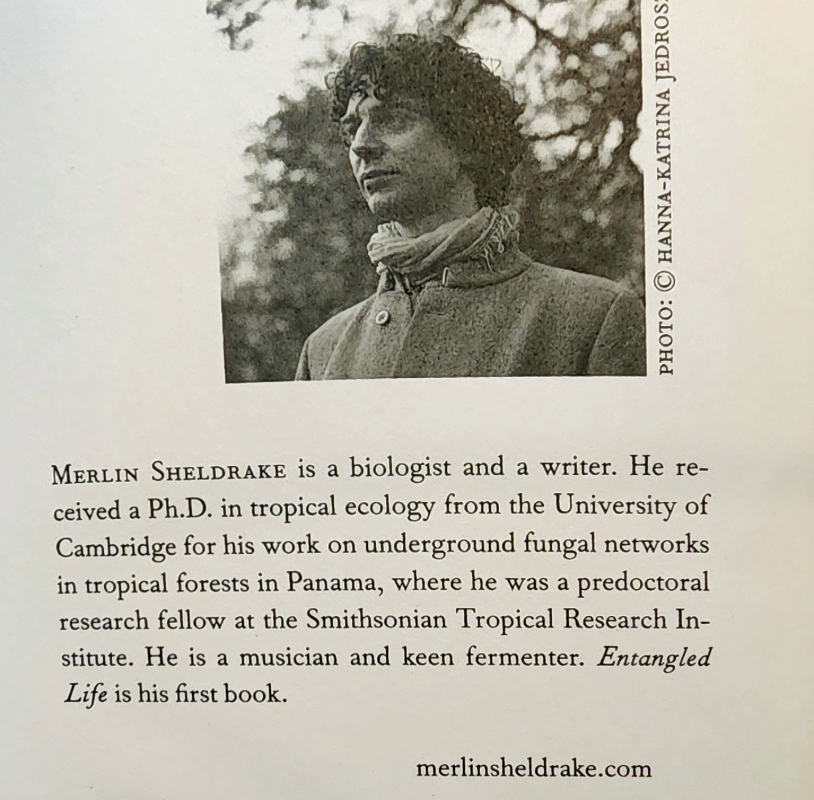

In this chapter, Sheldrake describes his own experience with use of LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) in a clinical setting and the use of both LSD and psilocybin by many others.

Sheldrake cites numerous examples of animals who seek intoxicants and psychoactive agents produced by plants and fungi. In many human cultures, such psychoactive agents have played key roles in religion and culture. Many such agents appear to loosen the individual’s sense of separate identity and to feel a unity with the cosmos. In the United States, the legal use of psilocybin and LSD ended by the early 1970s, though some research and clinical uses have been available since then. Some proponents of its use zealously endorse it both for therapeutic settings and for spiritual pursuits.

Sheldrake also describes the fungus Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, which produces chemicals that infect carpenter ants, controlling their minds so that the fungus can parasitize the ants’ bodies to procreate and disperse fungal spores. Ophiocordyceps has been called a “fungus in ant’s clothing” (p. 106).

Figure 09. Sometimes called a “zombie fungus,” Ophiocordyceps unilateralis can control the minds of ants as they parasitize them, using their body to produce and disperse their fungal spores. This image, by David P. Hughes, Maj-Britt Pontoppidan, was posted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ophiocordyceps, and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work, to remix or to adapt the work, as long as you provide attribution.

5. Before Roots 123–148

Green algae, the ancestors of all land plants, “began to move out of shallow fresh waters and onto the land” about 600 million years ago. “The evolution of plants transformed the planet and its atmosphere . . . . Today, plants make up [80%] of the mass of life on Earth and are the base of the food chains that support nearly all terrestrial organisms” (p. 123).

Even before the arrival of plants, however, “photosynthetic bacteria, extremophile algae, and fungi were able to make a living in the open air” on land (p. 123). These algae were rootless, though, unable to store or transport water or to extract nutrients from the land. Only by partnering with fungi, in mycorrhizal relationships were they able to do these things. These relationships paved the way for the mycorrhizal relationshps between plants and fungi today; more than 90% of all plants rely on these relationships.

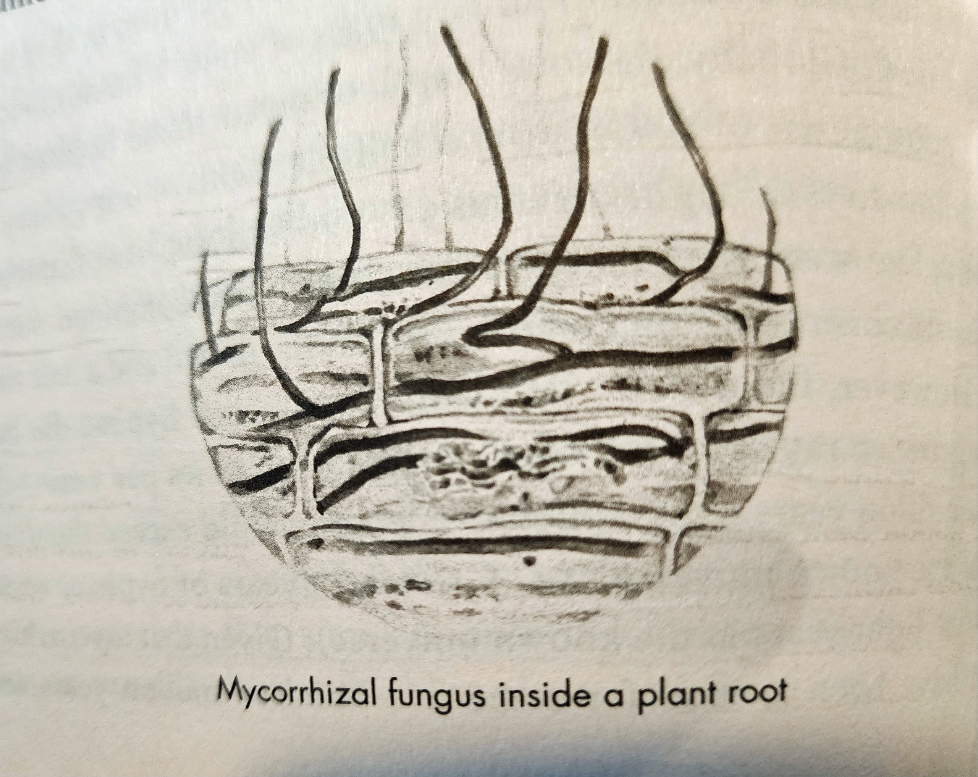

Figure 10. Mycorrhizal fungi live inside and/or outside of plant roots, yet remain separate organisms. Mycorrhizal fungi that live primarily inside plant roots are endomycorrhizal; ectomycorrhizal fungi live outside plant roots. Collin Elder drew this illustration (and the others in this book), using ink from deliquesced shaggy ink cap mushrooms.

Lichens aren’t the only partnerships between algae and fungi. When seaweeds wash up on shores, many seaweeds depend on fungi to nourish and hydrate them until they’re washed back out to sea.

Unlike the intertwined relationships of lichen, the mycorrhizal relationships between plants and fungi involve two separate organisms that form a symbiotic relationship. The fungi scrounge nutrients and water from the soil and provide those to the plant. The plant, in turn, uses those resources, combined with sunlight and carbon dioxide, to create sugars, which it feeds to the fungi. Each partner benefits from the relationship and is better able to thrive because of the partnership.

The fungi and the plant don’t just clasp one another, they intertwine; in many species, fungal hyphae move into and through the plant root’s cells. Some seeds (e.g., orchid seeds) won’t germinate until they’ve found their own fungi. Once they meet, they intertwine — not fusing, not exchanging genetic information, but interweaving — and grow together. “Mycorrhizal hyphae are [50×] finer than the finest roots and can exceed the length of a plant’s roots by as much as [100×]” (p. 127).

The mycelium of “mycorrhizal fungi . . . makes up between a third and a half of the living mass of soils” (p. 127). The hyphae of mycorrhizal fungi continually grow, die back, and grow some more.

Albert Frank coined the words symbiosis (in 1877), to describe lichen, and mycorrhiza (in 1885), while studying truffles and their relationship with tree roots.

J. R. R. Tolkien was inspired by mycorrhizal fungi when describing Sam Gamgee’s planting of saplings in Lord of the Rings.

In the Devonian period (300–400 million years ago), plants spread out worldwide, triggering a 90% drop in the amount of CO2, which prompted “global cooling.” Hmmm…

Plant growth is limited by the availability of nutrients, such as phosphorus. When mycorrhizal fungi provide adequate nutrients, plants can flourish, drawing down the amount of CO2. Then when individual plants die, they sequester carbon in their bodies, which the fungi help to bury in soils and sediments.

Mycorrhizal fungi also mine minerals from rocks, liberating calcium and silica, which then react with CO2 to create carbonates and silicates, pulling even more CO2 from the atmosphere. When these carbonates and silicates reach the ocean, marine invertebrates use the compounds to make their shells. After a given marine invertebrate dies, it sinks to the bottom of the ocean, adding its shell to the sea floor. More CO2 is removed from the atmosphere.

Meanwhile, the mycorrhizal fungi are providing 100% of the plant’s need for phosphorus, 80% of its need for nitrogen, as well as other vital nutrients, such as zinc and copper. Not to mention water. “In return, plants allocate up to [30%] of the carbon they harvest to their mycorrhizal partners” (p. 132). This mutually beneficial interrelationship has separately evolved more than 60 times in different fungal lineages.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the particular fungi with which a plant interacts affects many aspects of the plant, including its fruits’ flavor, juiciness, and sweetness. Even pollinators can discern a difference, affecting the attraction of bumblebees to the flowers of strawberry plants; some fungi seemed to prompt the plant’s flowers to be more enticing than other fungi. The particular fungus at a plant’s roots can affect not only the plant’s flavor and odor profile, but also the amounts of iron, carotenoids, and medicinal compounds concentrated in the plant.

“Plants and mycorrhizal fungi . . . certainly live entangled lives and have had to evolve ways to manage their complex affairs” (p. 135)

“Using information from [15–20] different senses, a plant’s shoots and leaves explore the air and adjust their behavior based on continuous subtle changes in their surroundings. . . . Meanwhile, a mycorrhizal fungus must sniff out sources of nutrients, proliferate within them, mingle with crowds of other microbes . . . absorb the nutrients, and divert them around its rambling network” (p. 135).

Plants and their mycorrhizal fungi are constantly negotiating their exchanges, sometimes offering more resources, sometimes offering smaller amounts or fewer resources. Supply and demand may affect these sophisticated negotiations, such as when fungi move resources from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. Both partners nonetheless work to maintain the relationship. Neither partner will skew the exchange in ways that keeps one partner from deriving benefits.

Fungi often determine which plants can grow where. If a given plant can find a fungus with which to form a mycorrhizal relationship, the plant can grow in this new location. If it can’t, it can’t. “Faced with catastrophic environmental change, much of life depends on the ability of plants and fungi to adapt to new conditions” (p. 142). Modern agricultural methods have dramatically increased crop yield, but those methods have come at a steep price — widespread environmental destruction and dramatic increases in greenhouse gas emissions. Despite astronomical uses of pesticides, which pollute air, water, and land, 20–40% of all crops are lost yearly due to plant pests and diseases. “Agricultural practices have ravaged the underground communities that sustain” food crops and other living organisms (p. 144).

Figure 11. These vegetables carry an “organic” label. Were they grown in a way that sustainably preserves the diversity of the mycorrhizal communities where they’re grown?

In contrast, sustainable farming practices maintain diverse mycorrhizal communities and host more fungal mycelium in the soil. “Mycorrhizal mycelium is a sticky living seam that holds soil together; remove the fungi, and the ground washes away. Mycorrhizal fungi increase the volume of water that the soil can absorb, reducing the quantity of nutrients leached out of the soil by rainfall by as much as” 50%. These fungi also bind carbon into organic compounds that support food webs. These fungi help plants to resist diseases by boosting the plants’ immune systems. Fungi “can make crops less susceptible to drought and heat, and more resistant to salinity and heavy metals. They even boost the ability of plants to fight off attacks from insect pests by stimulating the production of defensive chemicals” (p. 145).

6. Wood Wide Webs 149–174

“Gradually, the observer realizes that these organisms are connected to each other, not linearly, but in a net-like, entangled fabric. — Alexander von Humboldt” (p. 149)

Though most plants photosynthesize, thereby offering sugars to the fungi with which they interact, some don’t. A few plants don’t photosynthesize, aren’t green, and don’t offer sugars to the fungi with which they interact. In fact, these non-photosynthesizing plants survive only by depending on their mycorrhizal fungal partners. From what researchers have observed so far, these plants don’t appear to give anything in return to their mycorrhizal fungi. These fungi must also have relationships with photosynthesizing plants for their own survival. Thus, the photosynthesizing plants are supporting the non-photosynthesizing plants by way of their fungal partners.

Photosynthesizing plants are autotrophs, producing their own food; humans, other animals, and fungi are heterotrophs, having to obtain food produced by other organisms; non-photosynthesizing plants are mycoheterotrophs, relying on fungi to provide them with food — food the fungi obtained from their photosynthesizing plant partners. Some plants, such as all orchids, are mycoheterotrophs at some point in their development; most orchids are on a take-now-pay-later plan, returning the favor once they’re fully photosynthetic.

Figure 12. These mycoheterotrophic pink indian pipe plants can’t photosynthesize and must rely on their fungal partners to feed them; they’re not green, but they’re still shaped like plants. This image, by NH Magellan was posted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myco-heterotrophy, and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work, to remix or to adapt the work, as long as you provide attribution.

Plants (and fungi) seem to show generosity in other ways, too. A 1997 study showed that well-established birch trees donated carbon (which the birches had photosynthesized) to shaded fir seedlings, by way of their interconnected mycorrhizal fungi. Researcher Suzanne Simard documented the carbon transfer to the shaded seedlings, which weren’t able to photosynthesize much for themselves. That is, plants seemed to spread carbon from where it was plentiful (established trees) to where it was scarce (young, shaded seedlings). This observation prompted the coinage “Wood Wide Web,” in that mycorrhizal fungi interconnected trees in a forest, facilitating the transfer of resources from one tree to another. Plants also seem to be more generous with genetic kin than with strangers, and they share more mycorrhizal connections with kin than with strangers.

Since then, studies have shown transfers not only of carbon but also of other nutrients, such as water, as well as nitrogen, phosphorus, and others. These transfers aren’t trivial amounts. They substantially affect the partners involved in these transfers. In general, these transfers go from larger plants (with more resources) to smaller plants (with fewer resources). Also, plants that are dying will transfer their resources to younger, healthier plants.

Seasonal changes can reverse the donor–recipient relationship. For instance, deciduous trees, such as birches, photosynthesize abundantly during spring and summer; their leafy canopy shades nearby evergreens, limiting their ability to photosynthesize, so the deciduous trees transfer resources to the evergreens. In the fall and winter, however, the deciduous trees lose their photosynthesizing leaves, exposing the evergreens to more sunlight. In return the evergreens transfer resources to the deciduous trees.

Thus far, we have emphasized the plant side of this partnership, but fungi play important active roles in these relationships. Their ability to transport water and other resources, in any direction, is unparalleled in the living world; they can solve complex spatial problems, too. Also, fungi don’t need living plants to create complex networks, as they also specialize in decomposing dead plant materials. Some fungi specialize in consuming dead plants, rather than supporting living plants. It is through these multivariate fungal networks that many fungi can support some plants (e.g., young orchids) on a take-now-pay-later plan.

Not all mycorrhizal relationships benefit the plants. Some plants give more than they receive from their partnerships with mycorrhizal fungi. Also, some plants use their mycorrhizal fungal relationships to harm nearby plants, sometimes stunting their growth, sometimes killing them outright. The fungi in these relationships can inhibit the harmful connections or can exacerbate the situation. Fungi can even facilitate the transfer of genetic material from one plant to another.

Fungal networks can also aid in plants’ defenses. When broad-bean plants are being attacked by aphids, they can release a volatile compound that attracts parasitic wasps, which then prey on the aphids. Through a mycorrhizal network, nearby plants were also prompted to release volatile compounds to defend against an invading army of aphids. Similar findings were observed in tomato plants being attacked by caterpillars and evergreen seedlings being attacked by budworms. It’s not yet known whether the plant that sends these signals is intentionally alerting neighboring plants or if it’s simply screaming in agony and the neighboring plants happen to overhear the signals. No matter what, the fungi that facilitate these communications will benefit by having more of the plants in its network survive and thrive.

Not all trees in the Wood Wide Web have equal connections. Older trees serve as information hubs with myriad connections throughout the network; younger trees have relatively few connections. When commercial logging companies selectively hack down older trees — the most valuable timber for logging — they create devastating impact on the interconnectivity of the network, far more than would occur if they chose younger trees or even a mix of younger and middle-aged trees.

Figure 13. This potted evergreen can’t participate in a Wood Wide Web, but its forested cousins participate in complex networks, allowing deciduous trees and evergreens to send resources back and forth. Such interactions allow resources to go from trees that are photosynthesizing abundantly to trees with limited ability to photosynthesize.

“Fungal networks [constantly] reconfigure themselves — or ‘adaptively rewire’ — in response to new situations” (p. 173). Underused pathways break down or are pruned back; well-used pathways strengthen and enlarge. These pathways also include bacteria that migrate throughout the mycelial network.

7. Radical Mycology 175–201

Fungi specialize in decomposition and fermentation of organic materials. Without decomposition, life on Earth would be unsustainable. Fungi “are inventive, flexible, and collaborative” (p. 176).

Wood (in about 3 trillion trees) makes up about 60% of Earth’s biomass (the total mass of every living organism on Earth). Wood is a hybrid of cellulose, “the most abundant polymer on earth” and essential to all plant cells, and lignin, present in trees and much stronger and more complex than cellulose, able to sustain trees growing to towering heights. Lignin’s toughness makes it extremely hard to digest, such that only a few organisms can decompose it. White rot fungi do it better — and more prolifically — than any other organism. These fungi have highly adaptable enzymes to break down lignin in whatever form (whatever tree species) it takes.

Before these specialized wood-rotting fungi were prolifically decomposing trees’ lignin, dead trees accumulated on the surface of the earth, not rotting, continually accumulating. Over time, these organic materials were transformed into coal (and petroleum).

Though China and parts of Europe have long recognized the importance of some fungi, overall, fungi have been — and continue to be — underappreciated. On the Red List of Threatened Species, the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) evaluated the conservation status of only 56 species of fungi, compared with more than 25,000 plant species and 68,000 animal species. Needless to say, we haven’t a clue about the perils faced by fungi.

Figure 14. In A.D. 1000, a Chinese mycologist figured out how to farm shiitake mushrooms (another white rot fungus species).

In response to the neglect of mycology by the academic scientific community, numerous volunteer “citizen scientists” have taken an interest in fungi, some of them passionately so (e.g., a loose-knit organization, “Radical Mycology”). Among their activities are seeking ways to use fungi to solve some of our waste problems. For instance, used diapers form a significant portion of solid waste, but “a white rot fungus that fruits into edible oyster mushrooms — can grow happily on a diet of used diapers,” drastically reducing their mass and producing healthy, disease-free edible mushrooms.

“Palm and coconut oil plantations discard [95%] of the total biomass [they produce]. Sugar plantations discard” 83% (pp. 180–181).

Fungi have also been instrumental in reducing the hazards caused by disasters such as those involving radioactivity. Chernobyl and Hiroshima both were first reinhabited by mushrooms.

Fungi can also provide mycofiltration, removing infectious agents, as well as heavy metals and other toxins, from drinking water. In the process, they can salvage gold from electronic waste.

More than 750,000 tons of cigarette butts are discarded each year, releasing toxic residues.“Self-taught mycologist” Peter McCoy induced the fungal species Pleurotus ostreatus to break down cigarette butts, which contain toxins notoriously hard to degrade. These fungi, which readily decompose lignin from trees, are especially suited to decomposing these toxic butts and other toxic pollutants. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleurotus_ostreatus#Other_uses for additional examples of its uses in mycoremediation, as well as mycofabrication.

The use of these fungal decomposers of toxic pollutants has been called mycoremediation. They’ll decompose not only cigarette butts and radioactive materials, but also herbicides such as glyphosate and even neurotoxins involved in deadly weapons of gas warfare. They can “degrade pesticides (such as chlorophenols), synthetic dyes, the explosives TNT and RDX, crude oil, some plastics, and a range of human and veterinary drugs not removed by wastewater treatment plants, from antibiotics to synthetic hormones” (p. 185).

Fungi can also facilitate pathways for other organisms to join in the decomposition, such as by letting bacteria reach places they otherwise couldn’t. Researchers are also investigating whether “petrophilic” fungi and microbes can be used to decontaminate soils. Perhaps researchers could even find fungi or microbes to decompose polyurethane plastics. So far, mycoremediation is occurring on a small scale, but the hope is to be able to upscale these processes for more widespread use. If polluters are forced to pay for remediating the damage they’ve caused, they may be more willing to invest in such processes.

Enthusiastic fungi farmers have been plagued by difficulties with contamination of the fungi they grew. More recently, techniques have been devised to make it possible to farm fungi by simply using “a syringe and a modified jam jar” (p. 188).

On the other hand, termites have known how to farm a species of white rot fungus for thousands of years. “The termites chew wood into a slurry that they regurgitate in fungal gardens . . . The fungus uses its radical chemistry to decompose the wood. The termites consume the compost that remains” (p. 190).

Mycofabrication is another promising avenue for avocational mycologists and entrepreneurs. Portobello mushrooms are being studied as a possible alternative to graphite for making lithium batteries. The mycelium of some fungal species is being used as an effective substitute for human skin. Some companies are studying whether they can produce a vegan alternative to animal leather, and at least one company (Ecovative) is producing building materials (boards, bricks, tiles) and packing materials from mycelium. According to Ecovative, its mycofabricated building materials are fire retardant, stronger than concrete, lightweight, water resistant, and highly insulating. Ecovative uses different species and strains of fungi for different purposes. Sheldrake describes an impressive array of other mycofabricated products used in an array of settings (from fashion to military to disaster zones). Mycofabrication even inspired a character in a Star Trek TV series.

Often, these products are based on waste from other industries, such as sawdust or corn stalks. So mycofabrication is a win (making useful products) – win (getting rid of waste products) – win, because the resulting products are compostable, so after their useful life, they can be decomposed to make other products.

Extracts from wood-rotting fungi have also shown possibilities for a multitude of antiviral agents, such as fighting smallpox, herpes, and influenza. These antivirals were also used to help bees defend themselves against deadly viruses. It turns out that some bees had actually discovered antiviral fungi before humans did.

8. Making Sense of Fungi 202–222

We humans have always lived with yeasts on our skins, in our gastrointestinal tract and our bodily orifices, and even in our lungs. In addition, for millennia, we have used yeasts to ferment grains and other plant materials and to leaven our breads. According to Sheldrake, yeasts “are the simplest envelopes of eukaryotic [i.e., multicellular] life, and many human genes have equivalents in yeasts” (p. 202). Between 2010 and 2020, more than 1/4 of Nobel Prizes for Physiology or Medicine have been related to the study of yeasts.

Figure 15. Two common yeasts may be found in many household kitchens: instant dry yeast, used for making yeast-leavened bread, and nutritional yeast, which can be added to any breads and other foods, to boost their nutritional value.

“Any sugary liquid left for longer than a day [at room temperature] will start to ferment by itself” (p. 203). Given this yeasty predilection for fermentation, and the easy transformation from sugars into alcohols, it seems likely that humans have been imbibing the fruits of yeast’s labors throughout most of human history, with or without human intervention. It’s possible that the transition from nomadic hunter-gatherers to sedentary farmers is linked to the cultivation of grains and other crops to produce beer or bread. (Researchers seem to dispute which came first.)

Figure 16. Unlike other yeast breads, sourdough breads are made from “starter,” which contains an assortment of yeasts, depending on where the starter originated.

To ferment sugars into alcohol, “yeast does almost all the work. It likes to be warm, but not too hot, and reproduces most happily in the dark. Fermentation starts when you add the yeast to a warm sugary solution. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts sugar into alcohol and releases carbon dioxide. Fermentation stops when the yeast runs out of sugar or dies of alcohol poisoning” (p. 204). Sheldrake spent years finding and following historical recipes (e.g., from the 1600s) for yeast-fermented alcoholic beverages. To him, “fermentation is domesticated decomposition — rot rehoused” (p. 206). He also highlighted numerous mycophiles (e.g., Theophrastus) and mycophobes (e.g., Charles Darwin’s daughter).

“Toby Spribille makes the case that lichens have to be understood as systems. . . . they arise out of an array of possible relationships [among] a number of players” (p. 212). Likewise, plants and their mycorrhizal fungi don’t necessarily have to have either a mutually beneficial or a parasitic relationship. Their interactions can be fluid, dynamically changing. Mycorrhizal networks can be both cooperative and competitive, with shifting interactions. Fungal connections can deliver nutrients or poisons. Networked organisms evolve and involve, associating with one another.

About 10 million years ago, primates underwent a genetic mutation to be able to produce an enzyme that detoxifies alcohol we consume. Without it, primates who ate fermented fruits would have been poisoned by even small amounts of alcohol in overripened fruit. Other vertebrates experienced similar mutations (e.g., tree shrews).

Sheldrake described an experience in which he absconded with apples from a tree reputed to have belonged to Isaac Newton, borrowed an apple press to pulp the apples into juice, then naturally fermented the juice into cider (taking advantage of yeast naturally living on apple skins). The result: “The taste was floral and delicate, dry with a gentle fizz . . . delicious” (p. 222).

Sheldrake has suggested that just as symbiotic organisms interact across species boundaries, scientists who study them should interact across disciplinary boundaries: Mycologists, bacteriologists, botanists, neuroscientists, and others all have insights that can lead to mutually beneficial discoveries.

Epilogue: This Compost 223–225

As a child, each autumn, Sheldrake would rake leaves into a huge pile then leap into the pile and wiggle his way to the bottom of the pile. Over time, the leaf piles would compost from distinctive leaves into leafy soil and then into soil with leaves and finally just soil. Worms aided in the process, but young Merlin didn’t quite understand how. Through these repeated autumn experiences, he came to appreciate the decomposers of the world. There can be no composers without decomposers. “From this thought, from my fascination with the creatures that decompose, grew my interest in fungi” (p. 224). “Fungi might make mushrooms, but first they must unmake something else. . . . Fungi make worlds; they also unmake them” (p. 225).

[Back Matter] 227–353

- Acknowledgments 227–229

- Notes 231–282

- Bibliography 283–326

- Index 327–352

- [Merlin Sheldrake], 353

Text Copyright © 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

Where not otherwise indicated, photos are by Shari Dorantes Hatch, Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment