Kahneman, Daniel (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

I read Nobel-winning cognitive psychologist (and economist) Daniel Kahneman’s book several years ago, and I still often think about things Kahneman said. I decided you might enjoy hearing what he had to say, too. I hope so. Kahneman doesn’t say this, but I will. We humans are brilliant, with amazing brains and marvelous abilities to think. Part of our cleverness is that we look for ways to save time, take shortcuts, avoid hard work, and so on. That works great most of the time. Sometimes, however, our mental shortcuts lead us to believe in fallacies, skip over important information, make foolish decisions based on limited information, and so on. Kahneman’s book reveals many of the ways we do so, as well as a few ways we can try to avoid doing so when the situation is important, worthy of extra attention, and mistakes would be costly.

Figure 01. Years ago, Kahneman was interviewed by Ira Flatow, on the NPR (National Public Radio) show, Science Friday. In the interview, Kahneman said that people are mistaken to think that by reading this book they won’t make cognitive errors and will think more clearly. He noted that he wrote the book and still makes many cognitive errors. Apparently, being a Nobel laureate didn’t detract from his humility or his sense of humor.

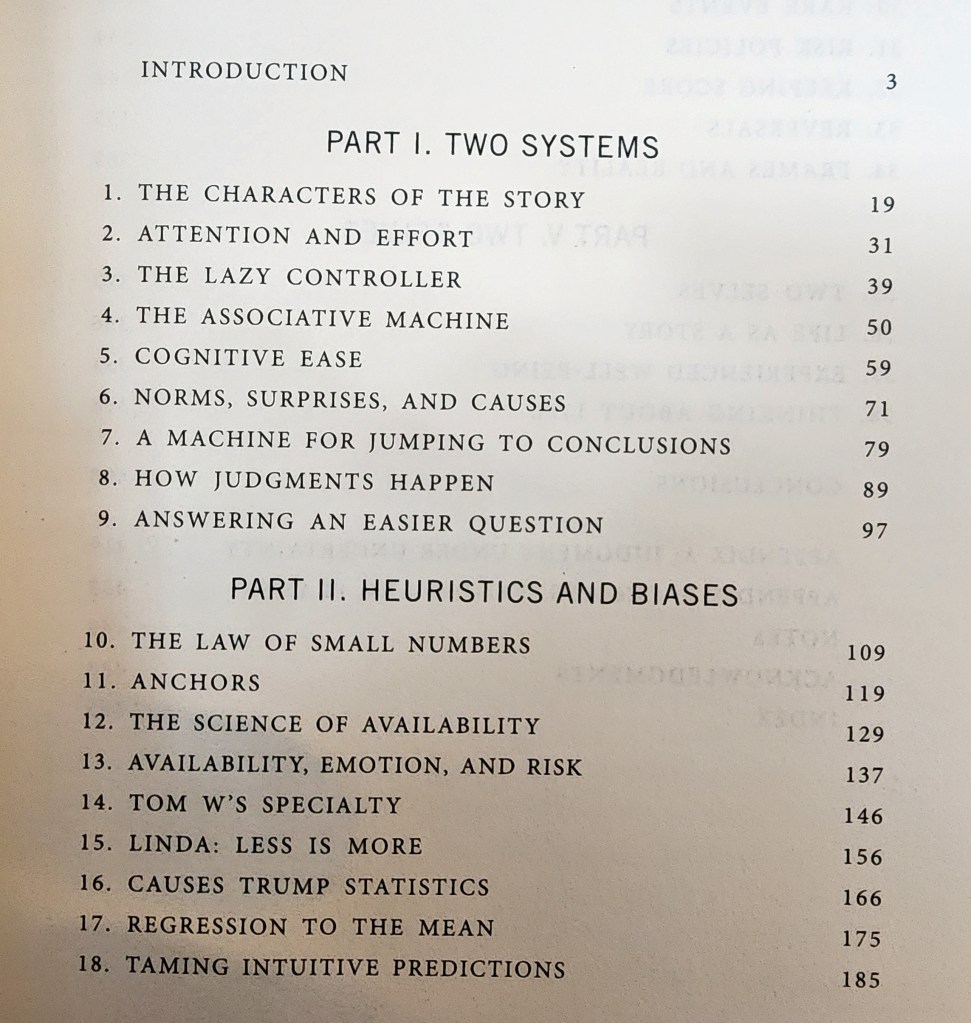

- Introduction, 3–15

- Part I. Two Systems

- 1. The Characters of the Story, 19–30

- 2. Attention and Effort, 31–38

- 3. The Lazy Controller, 39–49

- 4. The Associative Machine, 50–58

- 5. Cognitive Ease, 59–70

- 6. Norms, Surprises, and Causes, 71–78

- 7. A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions, 79–88

- 8. How Judgments Happen, 89–96

- 9. Answering an Easier Question, 97–10

- Part II. Heuristics and Biases

- 10. The Law of Small Numbers, 109–118

- 11. Anchors, 119–128

- 12. The Science of Availability, 129–136

- 13. Availability, Emotion, and Risk, 137–145

- 14. Tom W’s Specialty, 146–155

- 15. Linda: Less Is More, 156–165

- 16. Causes Trump Statistics, 166–174

- 17. Regression to the Mean, 175–184

- 18. Taming Intuitive Predictions, 185–195

Not included in Part 1 of this blog about Kahneman’s book is the second half of his book:

(Parts 2 and 3)

Part III. Overconfidence

Part IV. Choices

Part V. Two Selves

Conclusions

[Back matter, including appendixes, notes and index]

Figure 02. Kahneman’s book is >400 pages long, so I’m dividing my discussion of it into three parts. Here’s what will be discussed in the blog for Parts 2 and 3. In truth, I probably could easily have discussed this book in two parts, but both of my eyes will be undergoing cataract surgery soon, and I won’t finish my blog(s) about the remainder of the book before then. I anticipate that all will go well, but it’s my understanding that it may take weeks before my eyes have completely adjusted and I’m ready to do more reading and writing. My third blog about this marvelous book may have to wait until my eyes are fully back in working order.

Introduction, 3–15

Systematic errors, known as biases, occur “predictably in particular circumstances” (p. 4). For instance, the bias known as the “halo effect” skews our judgments to think more favorably of someone who has irrelevant favorable attributes; a physically attractive orator might be expected to be more knowledgeable than an unattractive one.

Most of us believe that we know what we are thinking and why we are thinking as we do. Most of the time, we think reasonably and draw reasonable conclusions. But not always. And we are usually the last to know — if we ever know — when we make errors in our thought processes. What’s more, most of us believe that most people generally think rationally, and that when they don’t, it’s because of emotional responses such as fear, hatred, or affection. Not so.

By four years of age, most of us are intuitively able to follow the rules of grammar of the language we speak. But even when we are adults, we are not good at intuitively reading and understanding statistics. According to Kahneman, “Even statisticians were not good intuitive statisticians” (p. 5). When we know little about a situation, and we’re asked to make predictions or judgments, we often use heuristics, shortcut rules of thumb.

For instance, we may consider resemblance, rather than statistical likelihood. When given a description of a bookish-sounding person, if we’re asked whether she’s more likely to be a librarian or a restaurant server, we probably focus on how much she resembles a librarian, not that being a restaurant server is statistically more likely.

The tendency to overemphasize “resemblance” is an example of the availability heuristic — whatever answer we can most easily recall from memory seems to us to be the best answer. We tend to leap on the most readily available answer when trying to answer a question. The availability heuristic explains why so many of us fear that crime is rampant, despite crime rates actually being quite low. We can so easily recall a news story about a recent crime, it certainly must be quite common — but it’s not. Similarly, we can much more easily call to mind airplane crashes but not car crashes, so we have an exaggerated fear of flying but an underestimated fear of riding in cars.

Not all intuitive judgments are fallible. Intuitions based on extensive knowledge are more likely to be accurate. For instance, experts in a particular field have extensive experience and practice in many aspects of their field. When they’re asked to make a quick judgment, they can recall from memory many relevant instances on which to make that judgment. Of course, they’re not immune to errors, but their errors are fewer and are less likely to be far off the mark.

Also, experts’ errors are more likely to be due to other factors, such as emotions, the halo effect, or considerations other than availability. For instance, even experts can fall prey to the affect heuristic, in which we make judgments or choices based on our feelings of liking or disliking of the person, the product, or the situation being considered.

A particularly troublesome problem is the intuitive heuristic, in which “when faced with a difficult question, we often answer an easier one instead, usually without noticing the substitution” (p. 12). For instance, if someone is deciding which of several companies in which to invest, the correct question is, “Which company is likely to provide me with the best return on investment during the time frame I wish to invest?” The best answer to that question will require extensive research, analysis, and consideration. It will be a slow process. Instead, the person might take a shortcut and ask, “Which company makes the products I like best?” Or “Which CEO seems the most personable?” Or even, “Which company have I heard of most often?” People taking these shortcuts may not even realize they haven’t asked or answered the right question.

The basis of the book’s title is that when we are faced with a decision for which we don’t have a ready answer, “we often find ourselves switching to a slower, more deliberate and effortful form of thinking. This is . . . slow thinking. Fast thinking includes both variants of intuitive thought — the expert and the heuristic — as well as the entirely automatic mental activities of perception and memory” (p. 13, emphasis added). Kahneman refers to fast, intuitive thinking as “System 1” and slow, deliberate thinking as “System 2.” Because it’s so common and so easily prone to errors — which are much more interesting than accurate slow thinking — his book focuses mostly on System 1, fast intuitive thinking.

In his book, Part 1 more clearly differentiates System 1 and System 2 thinking “and shows how associative memory, the core of System 1, continually constructs a coherent interpretation of what is going on in our world at any instant” (p. 13).

Part 2 focuses on judgment heuristics and on why it’s so hard for humans to think in terms of statistics. Why do we so easily lapse into associative or metaphorical thinking?

Part 3 addresses our overconfidence in what we think we know and understand, as well as our reluctance — even inability — to acknowledge just how little we do know and how little we can know about world. We resist being aware of just how much chance and luck affect events in the world. A particularly challenging heuristic is the hindsight illusion, our belief that we had accurately anticipated the unpredictable events that have occurred.

Part 4 “is a conversation with the discipline of economics on the nature of decision making and on the assumption that economic agents are rational” (p. 14). This chapter includes discussion of framing effects, “where decisions are shaped by inconsequential features of choice problems” and the “unfortunate tendency to treat problems in isolation” (p. 14).

Part 5 discusses “a distinction between two selves, the experiencing self and the remembering self, which do not have the same interests” (p. 14).

Part I. Two Systems

1. The Characters of the Story, 19–30

“System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control” (p. 20).

“System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration” (p. 21).

Our intuitive sense of ourselves is that we mostly think via System 2. In truth, System 1 is our go-to thinking process.

System 1 involves

- innate processes

- well-practiced responses

- acquired, practiced skills, including generalized ones, such as reading, or specialized skills, such as chess

- common links and associations

- deep knowledge of culture and language

System 1 thoughts “occur automatically and require little or no effort” (p. 21). We store this knowledge in memory and access this knowledge effortlessly, without intention. Some System 1 thinking occurs involuntarily.

Some activities can occur automatically or effortfully, via System 1 or System 2. For instance, motor activities (e.g., chewing) can require attention or can occur automatically.

System 2 thinking

- requires conscious attention and awareness

- can be used to modulate or to adjust motor activities

- involves self-monitoring for a given situation

- may involve analysis and evaluation

If attention flags during System 2 thinking, the thought processes are disrupted. System 2 requires effort, as well as focused attention. Attention is a limited resource, so it can easily be diverted. It’s possible to do more than one thing at a time, but only if they’re easy and don’t demand much attention.

When focused on a challenging task, we may be temporarily deaf and even blind to other stimuli. To make matters worse, we’re not aware of our own deafness or blindness.

In general, System 1 is our default mode of thinking, with System 2 still available in low-effort mode, using only a little of its total capacity. In general, System 2 just hums along in the background, waiting to be prompted to engage. When System 1 meets (a) a surprising situation for which it has no automatic response, or (b) a challenging situation needing a more complex response, it calls System 2 into action. System 2 then takes charge of the thought processes. Even in low-effort mode, System 2 is constantly monitoring our behavior, in order to prevent errors or to stop foolish or unwise actions, in which case it springs into effortful thinking.

Letting System 1 run the show most of the time is highly efficient, requiring much less cognitive effort than if System 2 controlled all thinking. When things get dicey, System 2 takes over and ensures that careful thinking prevails. When acting in familiar situations, with predictable occurrences, System 1 is a champ. Unfortunately, in less predictable situations, System 1’s biases, shortcuts, and heuristics can lead to errors in thinking. System 1 doesn’t grasp logic or statistics, and it likes answering inappropriate but easier questions, rather than harder but appropriate ones. System 1 is also completely automatic, outside of conscious control, and likely to make errors that it can’t detect. (For an example of the automaticity of System 1, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stroop_effect)

System 1 is also subject to illusions, including visual illusions. See for yourself. Look at the sets of lines in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%BCller-Lyer_illusion (before you read the article explaining the illusion).

Similarly, System 1 is subject to cognitive illusions. As with visual illusions, they’re automatic, effortless, inescapable, and not preventable. The best we can do is to try to recognize situations in which cognitive illusions may lead us to make mistakes. In high-stakes situations, it’s worth the effort to engage System 2 to analyze the situation. In low-stakes situations, however, it may simply not be worth the effort to engage System 2 to fight the illusion. Being hypervigilant requires effort — effort that may very well be spent otherwise in a low-stakes situation.

“Anything that occupies your working memory reduces your ability to think” (p. 30).

2. Attention and Effort, 31–38

System 1 actually regulates most of our sensations, perceptions, and actions most of the time, but System 2 believes that it is consciously doing so. System 2 is lazy and strives not to work hard, but it still likes to take credit for all our perceptions and actions, not acknowledging they mostly involve System 1. Sometimes, though, System 2 must take effortful, conscious control of our thinking.

You can get a pretty good measure of how much System 2 is involved in a task by videorecording your pupils; they’ll dilate when you’re engaging in mental effort. As mental effort increases, so does pupil size; when effort peaks and pauses, pupils contract. When the task exceeds the thinker’s mental ability, effort stops, and the pupils stop dilating and may even contract again.

Most of the time, we expend little mental effort, such as when chatting, but occasionally we cognitively exert ourselves (metaphorically jogging), and quite rarely, we boost our thinking into high gear (metaphorically sprinting), then we return to low-effort thinking (metaphorically strolling). These changes in effort correlate with changes in pupil dilation.

System 2 must judiciously expend its attentional capacity. When cognitive processing might overload the attentional capacity, System 2 focuses attention on the most important cognitive task and attends to other cognitive processing only if there’s spare attentional capacity. That’s how it can be easy for someone to be unaware of other features of the environment while engaged in a demanding cognitive task. Nonetheless, if a threatening stimulus appears during this process, System 1 will interrupt and take over cognition before System 2 is even consciously aware of the threat.

With increasing practice at a cognitive task, skill increases, and the need for effortful attention to the task declines. Innate talent and intelligence have a similar effect, requiring less effort for a given cognitive task. “Laziness is built deep into our nature” (p. 35), so we typically seek the least effortful way to achieve a goal.

System 1 can easily discern simple relationships (e.g., “Those flowers look alike”) and can integrate information about one thing (e.g., characteristics of a librarian), but it can’t handle multiple topics at once, and it can’t use statistical information about any topic. System 2 can hold multiple ideas at once, can integrate information, can make comparisons based on multiple attributes, can make informed choices among multiple options, and can apply rules to complex situations.

System 2 can use the brain’s executive function to organize memory to carry out a task, overriding System 1’s habitual responses. System 2 is particularly challenged when handling more than one task at a time. When time pressure is added, System 2 must exert considerable effort to switch tasks back and forth, requiring attention and the use of working memory. When multiple tasks push the boundaries of working memory, System 2 must switch items in and out of working memory, using lots of effort, all of which is made more challenging in the presence of time pressures.

Even people who engage in thinking as an occupation rarely engage in demanding effortful thought for long periods of time. Instead, we divide difficult cognitive tasks into multiple easier steps, and we use long-term memory and paper/pen to minimize overload of working memory.

3. The Lazy Controller, 39–49

Physical effort and cognitive effort are interrelated. When we are exerting intense physical effort, we can’t exert intense cognitive effort, and vice versa. When we are walking at our natural cruising speed, we can use some attention and effort on other low-key cognitive tasks, such as chatting with a friend. One way to look at it is that if we’re physically strolling, we can probably also cognitively stroll.

System 2 also has a natural cruising speed, requiring little effort and little strain on our attentional resources. If we’re engaged in intensive cognitive effort, it may be impossible to walk, even at a leisurely pace; sitting is preferable to standing, too. System 2 has a limited budget of attention and effort. If we are using some of it for (a) added physical exertion, and (b) added self-control to continue with exertion, we’ll have little left to perform any other cognitive tasks.

To maintain a coherent thought process, cognitive exertion requires self-control, as well as mental energy, and our naturally lazy System 2 tries to minimize this exertion. Time pressures and multiple tasks can contribute to the process’s difficulty and need for exertion.

At times, however, our cognitive processing can slip into flow, in which attention seems effortless. “Flow neatly separates the two forms of effort: concentration on the task and the deliberate control of attention. . . . In . . . flow, maintaining focused attention . . . requires no exertion of self-control, thereby freeing resources to be directed at the task at hand” (p. 41).

Both self-control and cognitive tasks use energy and attention from System 2, so at times when System 2 is focused on cognitive tasks, it may not divert energy or attention to self-control. When System 2 is diverted and self-control isn’t getting attention or energy, System 1 can take advantage, choosing behavior that wouldn’t be as likely when self-control is more accessible. Inappropriate language, impulsive behavior, poor judgment are all more likely when System 2 is cognitively busy. Of course, sleep deprivation, intoxication, or anxiety can have similar effects.

“All variants of voluntary effort — cognitive, emotional, or physical — draw at least partly on a shared pool of mental energy” (p. 41). System 2’s effort, exertion, and energy all draw on the same resources, and they’re all tiring. Cognitive, emotional, or physical exertions may all be mutually exclusive. Using energy for one means having less energy available for others.

Exerting self-control requires effort, and when we have less energy, it’s harder to exert self-control. Almost all situations requiring self-control involve conflicting impulses and the suppression of a natural tendency. If we’re exerting self-control in one area of our lives, it leaves less energy to do so in another area, but high motivation can boost effort and self-control.

Cognitive tasks have physical limits in working memory. Once those limits are reached, motivation and effort can’t override those limits. Mental energy is also physiological. If we use up glucose through cognitive exertion, emotional exertion (e.g., self-control), or physical exertion, we’ve depleted the blood glucose. It’s possible, however, to boost blood glucose by ingesting glucose, making available more energy for exertion. In experiments, volunteers were asked to exert self-control; half were given sugared lemonade, half were given lemonade with artificial sweetener. The ones who drank actual sugar were better able to exert self-control.

When analyzing the behavior of judges, judges who were tired or hungry denied parole more often, rather than carefully analyzing each situation.

Kahneman gave this example of a logical syllogism:

● All roses are flowers

● Some flowers fade quickly

● Therefore, some roses fade quickly

Most college students saw no flaw in the logic of this syllogism. (Actually, it’s not known whether any roses are among the flowers that fade quickly.)

Because we humans rely on the availability heuristic, basing our judgments and reasoning on the availability of information in our memories, people with richer information bases will make fewer errors when applying this heuristic. That is, people who have a greater wealth of accurate information in memory will be more likely to recall accurate information than people with less accurate information in memory. People with less information can compensate for this lack by using System 2 to more carefully check for additional information.

The ability to delay gratification at age 4 years seems to be related to intelligence test scores as young adults. In any case, the ability to delay gratification is related to the brain’s executive control of behavior. (See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanford_marshmallow_experiment for more about Walter Mischel’s marshmallow test, which first revealed the importance of delayed gratification.) Parenting techniques can also affect this ability.

“High intelligence does not make people immune to biases. . . . rationality should be distinguished from intelligence” (p. 49, emphasis in original).

4. The Associative Machine, 50–58

When reading the words

bananas . . . . . . vomit

Your automatic System 1 response is disgust, with increasing heart rate, sweating, and raised arm hairs. Furthermore, you have easier mental access to words such as nausea, sick, stink, as well as the words yellow and fruit. You’ll also more readily recall situations and events associated with vomiting. All of these cognitive changes are due to associative activation, which occurred effortlessly, out of your conscious control, and possibly despite your conscious efforts not to make these changes. Once started, this activation continues to spread. Each word in the cascade “evokes memories, which evoke emotions, which in turn evoke facial expressions and other [physiological] reactions. . . . All this happens quickly and all at once, yielding a self-reinforcing pattern of cognitive, emotional, and physical responses that is both diverse and integrated — it [is] associatively coherent” (p. 51, emphasis in original).

“Cognition is embodied; you think with your body, not only with your brain” (p. 51).

In 1748, David Hume “reduced the principles of association to three: resemblance, contiguity in time and place, and causality” (p. 52). Kahneman adds other associative links besides these three, such as links between something and its properties (e.g., bananas link with yellowness) and links between something and its category (e.g., bananas link with fruit). What’s more, all of these links — activations — occur simultaneously or nearly so, and mostly outside of conscious awareness.

“You know far less about yourself than you feel you do” (p. 52).

If you read these letters

S _ O _ ? _ P

one of two words may leap to mind. If you’ve read the word “EAT” or you’re thinking about food, you’ll probably think of “SOUP,” but if you’ve read the word “WASH” or you’re about to shower, you’ll probably think of “SOAP.” Which word you conjure is the result of the priming effect. Once you settle on “SOUP,” you’ll be primed to think of other food-related ideas, as well as perhaps where you were or what you were doing when you last ate soup. These associative activations may ripple out to other, looser associations (e.g., your grandma who made you soup, a childhood experience of being home from school and eating soup).

Even implicit associations may activate a response. For instance, when participants were prompted to think about words associated with elderly people, they physically walked more slowly than when they weren’t prompted in this way. They literally embodied their association with the elderly. The reverse effect worked, too. When asked to walk very slowly, participants were primed to think of old age. This effect works for facial expressions, too.

When we feel amused, we tend to smile. Surprisingly, when people are asked to hold a pencil between their teeth lengthwise (effectively creating a smile), they more readily found cartoons to be humorous. When asked to hold the pencil by pursing their lips around the tip of the pencil (effectively creating a frown), they less readily found cartoons funny. A similar effect occurs with physical gestures. When asked to nod their heads (“yes”) while listening to an editorial, listeners were more likely to agree with the message than when asked to shake their heads (“no”) while listening.

When primed with symbols of money (words or images), participants became more selfish, less altruistic, less desirous of social interaction, but also more independent. More ominously, frequently reminding people of their own mortality “increases the appeal of authoritarian leaders” (p. 56). Few of us like to think that we would be primed in these ways, but those beliefs are coming from System 2, which is completely unaware of these priming effects.

My own take-home from this chapter:

● To decrease my intake of sweets and fatty foods, I need to find ways to NOT prime my desire for these foods.

● To increase my amount of exercise, I need to prime my desire to get exercise.

● Think of ways to prime myself to be more thoughtful, considerate, cheerful, and kind.

5. Cognitive Ease, 59–70

One of the many ways System 1 monitors our functioning is to consider cognitive ease, which can range from easy to strained. Easy means no threats, no problems, no need to redirect attention to something new or surprising; strained means that a threat or a surprising situation requires attention and effort to be directed to the new stimulus. Situations of cognitive ease involve familiarity, good feelings and moods, trustworthiness, effortlessness, association with a positively primed idea, a repeated experience, and a clear understanding of the situation.

Furthermore, anything that facilitates cognitive ease will foster feelings of familiarity. In contrast, when you’re experiencing cognitive strain, you’re more suspicious, attentive, and vigilant, less comfortable, more careful to avoid making mistakes, but you’re also less creative and less intuitive than when feeling less strain.

Repetition fosters familiarity, which thereby increases cognitive ease. What feels familiar also feels true, believable. If a statement includes a familiar (repeated) phrase, it feels more trustworthy, more believable, truer. When trying to persuade listeners, by including familiar phrasing, you foster feelings of trustworthiness and believability. If you’re trying to persuade readers with a printed message, you can enhance its believability in these ways:

- Use high-quality paper, with high contrast between the text and the background.

- If you’re using color, print your text in bright blue or bright red, not in “middling shades of green, yellow, or pale blue.”

- Use simple language whenever possible, avoiding complex language, and definitely avoid using pretentious language. Choose words (and names) that are easily pronounced.

- Avoid overly long or unfamiliar words unless they’re absolutely necessary for clarity or specificity of your message.

- To increase the believability, memorability, and perceived insightfulness of your message, use rhyming verses (e.g., “A fault confessed is half redressed,” pp. 63–64)

Ways to increase the believability of a statement:

- Strongly link the assertions to existing beliefs and preferences, ideally doing so by way of logic or associations

- Cite a source for the statement as being a trusted and well-liked source

It’s possible to be believed through pure logic, sound reasoning, and trustworthiness, but System 1 is lazy, and superficial factors may be more likely to be believed than factors requiring help from System 2. If listeners or readers aren’t highly motivated to make an effort to follow reasoning and logic, it won’t play a big role in the believability of your message.

Intriguingly, in situations of cognitive strain, people are less likely to make errors than in situations of cognitive ease. That’s because in situations of cognitive strain, System 1 recruits help from System 2, which more carefully addresses the problem and makes fewer errors. [My note. There’s a sweet spot for cognitive strain, though. In situations of too much strain, causing cognitive depletion, the error rate rises again, as System 2 is exhausted.]

Cognitive ease is associated with positive feelings. For instance, when companies first issue stock, the companies with easily pronounceable names sell more stock than companies with names not easily pronounced. Similarly, companies with trading symbols (e.g., KAR) that are easily pronounced outperform companies with unpronounceable trading symbols (e.g., PXG).

In the mere exposure effect, simply having repeated exposure to a name or an idea or a thing enhances feelings of familiarity and thereby positive attitudes toward the name, idea, or thing. This effect happens outside of conscious awareness, so even if you’re unaware of the repeated exposures, you may develop a familiarity with the stimulus and may feel more positively toward it. Being wary of novel stimuli makes sense, in evolutionary terms, and losing that wariness after repeated safe contacts makes sense, too.

About 1960, Sarnoff Mednick observed that “creativity is associative memory that works exceptionally well” (p. 67). People are remarkably adept at intuiting associations among words, which they can do far more quickly than conscious awareness would allow. Being in a good mood made these intuitive associations twice as accurate. When System 1 is happy, it can work quite well to intuit associations. When we’re in a good mood, we’re more intuitive and more creative, but we’re also less vigilant, analytical, and suspicious, and we’re more gullible. When we’re in a bad mood, we’re less gullible, and we’re more vigilant, analytical, and suspicious, but we’re also less creative and less intuitive. This, too, makes evolutionary sense. When we’re in a good mood, things are probably going well, so we can let our guard down; when we’re in a bad mood, things aren’t going well, so we should be more vigilant.

Here’s my pitch for why to have a good editor: When text is easier to read, the reader will be more predisposed to believe it and to like it.

6. Norms, Surprises, and Causes, 71–78

“A capacity for surprise is an essential part of our mental life” (p. 71). Surprises arise when our expectations are violated. Some of these expectations are conscious (and involve System 2), but most are outside of our awareness (and involve System 1). System 1 monitors these “passive expectations” and responds whenever the current situation violates these expectations.

We rely on our normative understandings of the world and of words to comprehend what we read or hear. Anomalies puzzle us because they violate our normative understandings. However, very little repetition is needed before a novel situation will feel normal. We can communicate with other people with whom we share normative understandings about the world and about the words we use.

When we have limited information about the causality of an event, we let System 1 pull together easily accessible information to find or create a coherent, plausible story about the cause of the event. Often, we infer causality by noticing correlations among events or among features of events. These inferences are strengthened by repeated observations of correlations. We’re also predisposed to infer intentional causes for events, even attributing intentions to personality traits. We’re especially likely to attribute causality incorrectly in situations that would require statistical reasoning to assess actual causality. Statistical thinking never occurs via System 1, and it only occurs in System 2 when the thinker has had at least some training in statistical reasoning.

7. A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions, 79–88

System 1 readily jumps to conclusions, which saves us time and effort. If the situation is familiar, its conclusion is probably correct. If occasional mistakes aren’t too costly, you might as well go ahead and rely on System 1’s hasty conclusions. Unfortunately, if the situation is unfamiliar, System 1 is more likely to make mistakes. In situations where mistakes will be costly, it’s a bad idea to rely on System 1’s easy, effortless conclusions.

When we’re in an ambiguous situation, with ambiguous stimuli, System 1 will leap to a definite conclusion, ignoring the ambiguity. System 1 won’t carefully consider the alternative options of an ambiguous situation and will mindlessly, unconsciously, and effortlessly leap to a single conclusion. System 1 might happen to guess correctly, . . . but it might not. System 2 will never even be aware of the options discarded by System 1. System 1 believes in the conclusion it has reached and doesn’t doubt it for a moment.

Only if System 1 can’t leap to a definite conclusion will it engage System 2. Ambiguity and uncertainty are the forte of System 2. Whereas System 1 seeks to believe what it sees, hears, and reads, System 2 will use mental effort to evaluate a situation and to check whether a statement is true. Like a scientist, System 2 will try to find information contravening the statement and testing the veracity of the statement. If System 2 is already busy with other cognitive (or physical) tasks, or System 2 is tired, depleted, or just being lazy, it will relinquish this effortful pursuit of truth and will fall back on System 1’s beliefs.

On hearing a statement, System 1 is gullible and will probably believe it without question. It probably won’t engage System 2, which is in charge of doubting, disbelieving, questioning. That’s especially true in cases of confirmation bias. In confirmation bias, we tend to search for information (in our memory) that confirms what we already believe, or at least what we have heard or read. The wording of a statement or question can also engage confirmation bias, in that it predisposes us to find information that confirms the implicit statement. For instance, if we hear, “Is Susie generous?” we are predisposed to find information that agrees with the implicit assertion that Susie is generous. If, instead, we’re asked, “Is Susie tight-fisted?” we are predisposed to find information that agrees with the implicit assertion that Susie is tight-fisted.

One of the other biases that System 1 uses is the “halo effect” (mentioned in the introduction). If we have a positive feeling toward someone (because we like the person’s appearance, career, political affiliation, etc.), we will be biased to expect other positive attributes about the person (e.g., intelligence, kindness, knowledge). On the other hand, if we have a negative feeling toward someone (e.g., due to the person’s mannerisms or religious affiliation), we’re predisposed to expect other negative attributes about the person (e.g., stinginess, inconsideration, ignorance).

Even the sequence in which we hear a series of descriptions will affect our overall impression. Kahneman gives this example (from psychologist Solomon Asch):

Alan is intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, envious

Ben is envious, stubborn, critical, impulsive, industrious, intelligent

On hearing these descriptors, most of us have a more favorable view of Alan than of Ben, even though careful review of the list shows that both men have exactly the same descriptors. When we meet someone new, the order in which we notice particular attributes of the person probably arise by chance, but that sequence will probably affect how we view that person. If we watch a person holding the door for a parent carrying bags of groceries, then we see that person rushing ahead of someone in a grocery line, we may have a more favorable view than if we saw those behaviors in the reverse order.

When working in a group tackling a tough problem, it’s best if each member of the group does separate research and formulates an independent idea about how to tackle the problem. Only then should the group come together to discuss their various approaches. This method makes it more likely that group members will think independently instead of just following along with what was said by the first person who spoke.

System 1 quickly and easily formulates a narrative about a situation by drawing on the most readily available information in memory. It makes no effort to evaluate the accuracy of the information, to seek additional information, or even to consider other narratives that might coherently explain the situation. Kahneman (and his collaborator Amos Tversky) came up with an acronym for this tendency: WYSIATI — What you see is all there is. Don’t consider the possibility that there may be other contradictory information, alternative explanations, or even superior information or explanations.

What’s more, we have greater confidence in the story created by System 1 if it was created quickly and easily. Considering any contradictory information may reduce the story’s coherence and therefore decreases our confidence in the story. We simply don’t consider the effects of using one-sided, poor-quality information when determining our confidence in the story created by System 1.

Here are some of the biases linked to the WYSIATI tendency of System 1:

- Overconfidence — Our degree of confidence in System 1’s story about the situation has absolutely no relationship to the quality or the quantity of the evidence used in creating the story. All doubt and ambiguity are ignored.

- Framing effects — How something is worded or presented powerfully affects how we see it. Which would you rather eat: a sandwich that is “90% fat-free,” or one that is “10% fat”? Would you rather have a surgery with a 95% survival rate, or one with a 5% mortality rate?

- Base-rate neglect — In the introduction, when we heard about a bookish woman, we thought it more likely that she was a librarian than a restaurant server, despite the fact that the base-rate likelihood of a woman being a restaurant server was much greater.

8. How Judgments Happen, 89–96

System 1 continuously monitors the environment and effortlessly, unconsciously, and unintentionally assesses it, using readily available information from memory. These effortless assessments generate intuitive judgments. The questions most important to System 1: How’s it going? Is everything going pretty much as expected? Are there any threats present? How about any major opportunities? If something new comes up, should I avoid it or approach it?

When System 2 is engaged (which is not occurring continuously), System 2 directs attention to tackle any number of simple or complex questions and to make various simple or complex evaluations, actively searching memory and other sources of information to find answers.

When we meet someone new, System 1 quickly judges, Is this person threatening?, and Is this person trustworthy? Facial expressions and other cues help System 1 to make snap judgments about this person. Somewhat surprisingly — and reassuringly — some studies suggest that when we’re voting for a leader, we’re more likely to choose someone we rate highly in terms of perceived competence than in terms of likability. Not quite so reassuringly, we’re more likely to rate a candidate as competent if the candidate has “a strong chin with a slight confident-appearing smile” (p. 91). This likelihood was greater for voters who were poorly informed and who watched more television, and it was less for well-informed voters who watched less television. Kahneman calls this appearance-based rating of competency a judgment heuristic, a shortcut with other aspects, as well.

Some tasks and judgments are easily handled by System 1, such as

- assessing the average length of a series of lines

- recognizing the colors of lines

- judging when lines are or are not parallel

- guessing which of two trays of objects has more or fewer items

- make judgments based on prototypes or exemplars, figuring out which items are more or less similar to the exemplars

- translating intensity from one category or dimension to another, such as translating height to loudness or to speed or to volume/size

System 1 does not, however, have a facility for adding numbers or lengths, and it tends to ignore quantity when making assessments in an emotional context.

System 1 can, however, continuously cognitively construct the three-dimensional (3-D) environment it sees, effortlessly and unintentionally. This 3-D mental model includes the shapes of objects, what they are, their position in space, and so on.

System 1 may sometimes consider irrelevant information (what Kahneman calls a “mental shotgun,” referring to the excess spray of pellets by a shotgun). For instance, when listening to a series of word pairs, participants were asked to tell whether each word pair rhymed. When the words were also spelled similarly (e.g., “vote” and “note”), participants answered more quickly than when they weren’t (e.g., “vote” and “goat”). That is, the irrelevant spelling difference impeded their response to the question.

System 1 also readily perceives metaphors, but it has to get help from System 2 to use extra mental processing to differentiate literal from metaphorical statements.

9. Answering an Easier Question, 97–105

Thanks to System 1, most of the time, we have intuitive feelings about our experiences, which give us a sense of knowing about and understanding our environment and our own experiences in it.

When System 1 confronts a hard question, if it can’t quickly find an answer, System 1 won’t try to answer the hard question. Instead, System 1 will find a related question that’s easy to answer and will answer that related question instead.

“The technical definition of heuristic is a simple procedure that helps find adequate, though often imperfect, answers to difficult questions. The word comes from the same root as eureka” (p. 98). Problems of probability are particularly likely to be solved using heuristics. Most of us have trouble judging probability, so when faced with questions of probability, we will make a judgment related to the probability question, and we’ll often think we’ve answered the probability question itself.

For instance, if we’re asked, “How popular will the president be six months from now?,” we’re likely to substitute that question by answering the question, “How popular is the president right now?” or perhaps even “How popular do I hope the president will be in six months?” (p. 98). Another common heuristic involves intensity matching. For instance, instead of answering “How much money should be spent to save endangered species?,” which would require information gathering and evaluation, we may match the intensity of how we feel about saving endangered species to the amount to spend on saving them. If we care deeply about saving them, we’ll match that intensity to a large amount of money.

By substituting answers to probability questions with answers to heuristic questions, we feel we have answered the question, without having to go to the trouble of actually trying to figure out the correct answer. When System 1 effortlessly uses association or intensity matching to answer a question, System 2 can respond in one of two ways: (1) rubber-stamp the answer, or (2) use additional information to analyze the situation and to modify the answer. More often, System 2 responds in the first way.

When viewing 2-D images showing linear perspective, we automatically and effortlessly perceive the images as 3-D, the 3-D heuristic. If we’re then asked to make judgments about the image without considering three dimensions, we simply can’t tune out our 3-D perception.

When asked to comment on our overall happiness over time, our immediate mood powerfully affects our answer.

We often apply the affect heuristic when assessing risks versus benefits of particular policies, things, or experiences. Specifically, our attitudes toward those policies, things, or experiences dominate our assessments. For what we like, we perceive greater benefits and fewer risks; for what we dislike, we perceive greater risks and fewer benefits. As we obtain new information, we can modify our assessments, but in general, we use the affect heuristic unless we gain information to the contrary.

In regard to attitudes, System 2 typically marshals its resources merely to bolster the attitudes held by System 1. Sometimes, however, System 2 will search memory more deeply, make complex computations, make comparisons and choices, and plan, despite what System 1 believes. Most of the time, however, “an active, coherence-seeking System 1 suggests solutions to an undemanding System 2” (p. 104).

Figure 03. Kahneman uses this chart to illustrate aspects of System 1. (I apologize for my defacement on the chart; I didn’t realize that anyone else would be looking at it!)

Part II. Heuristics and Biases

10. The Law of Small Numbers, 109–118

System 1 can quickly, easily, and effortlessly identify causal connections between events — sometimes even when they’re not causally connected. System 1 has little ability to consider statistics that affect the probability of an outcome, especially if the statistics aren’t causally linked to the outcome.

Statistics can be particularly problematic when they’re based on small sample sizes (e.g., small populations, small groups of people within a population), rather than on large sample sizes (e.g., large populations such as data from the U.S. Census, or large samples from within a population). Small samples can vary so widely that they can lead to extreme outcomes in the data. For instance, if a study compared the rates of high-school graduation in a rural mountain community with the rates in a rural desert community, if there were big differences in graduation rates in those communities, those differences wouldn’t necessarily tell you much about whether living in the mountains or in the desert was better for high-school graduation. The samples are just too small to infer much from those results. Either or both of the samples could reflect extreme results that distort the data.

When evaluating data, System 1 suppresses doubt (e.g., based on small sample size) and ambiguity, and it leans toward certainty, creating a coherent story about the data, which further bolsters certainty. System 2 fosters doubt and allows for ambiguity, but doing so requires effort, which neither System 1 or System 2 are eager to do unless the stakes are high for any inaccuracies.

We tend to exaggerate the consistency and the coherence of what we observe. When what we observe doesn’t make sense, we distort what we perceive to make sense of it. We also have a predilection for causal thinking, so when we see truly random events and occurrences, we tend to perceive causal links that don’t exist. Our minds naturally seek patterns, so we attribute intention and causality to patterns that are really just random co-occurrences. We cannot believe that regularities and patterns are simply a part of random processes. For instance, look at the following three sequences:

BBBGGG

GGGGGG

BGBBGB

Are each of these sequences equally likely to occur? Intuitively, we say, “NO!” The third sequence seems much more likely than the first two, but in fact, each sequence is equally likely. When we see the first two patterns, though, we think that they cannot simply be random occurrences; there must be a cause creating those patterns. Much more of what we observe is random than our minds want to believe. When using our intuition about what we observe, we’re far too unwilling to realize that most of what we observe is a result of randomness. Much of what happens in the world happens by chance.

We all too often pay little attention to the reliability of information we’re hearing or reading, focusing only on the content, which may or may not be accurate.

11. Anchors, 119–128

The anchoring effect is what happens when a person is prompted to think about a particular number and then is asked to estimate a given amount or quantity, and the first number affects their estimate of the second number. The anchor number — the first number the person is prompted to think about — will skew the person’s estimate of the amount or quantity. For instance, suppose you’re asked, “How much younger was Gandhi than age 114 when he died?” What if, instead you’re asked, “How much older was Gandhi than age 35 when he died?” You would probably answer the first question with a much higher age than you would answer the second question. (He was 78 years old when he died.)

Even System 2 can be influenced by anchoring effects. System 2 may take note of the anchor and then make deliberate adjustments away from the anchor, using other available information. Unfortunately, such adjustments may be inadequate in the face of (a) physical or mental exhaustion or depletion, (b) inattention due to diverted attention, or (c) uncertainty as to what other information may be needed to make further adjustments.

The anchoring effect is one type of priming effect, in which a suggestion prompts us to seek confirming evidence of the suggestion. System 1 is particularly susceptible to the priming effect, as its natural tendency is to seek confirmation of information, rather than to question it. When multiple people are asked to give estimates in the presence of the anchoring effect, it had a 55% impact on the answer they gave. Even for experts, the anchoring effect had a 41% impact on their answer. (If the anchor had no effect, the impact would be 0%; if the anchor was always chosen as the answer, the impact would be 100%.) Anchoring effects are particularly potent when money is involved. Real-estate brokers use the anchoring effect to elicit higher bids; bazaar and market-stall sellers do likewise.

Intriguingly, anchors continue to have about as much impact if the person believes that the anchor is chosen at random and has no real bearing on the situation. Even when the amount of information is slight, and its quality is poor, System 1 will still believe WYSIATI (what you see is all there is), not questioning the reliability of the information. On the other hand, when people are cautioned to think of reasons that the anchor shouldn’t be used as a guide, they engage System 2, and the anchoring effect is reduced or even eliminated.

Anchors can powerfully prime our associations, thereby affecting our thoughts and actions dramatically. Many other priming effects likewise prompt powerful associations that deeply influence our thoughts and actions. To combat these priming effects, we must consciously become aware of the priming and work hard to combat its effects.

12. The Science of Availability, 129–136

When using the availability heuristic, the more readily we can recall/retrieve instances of a category or of an event, the more common and true we believe it to be. If we can easily retrieve particular instances (e.g., blackberries) of a category (e.g., fruit), the more common and representative we believe it to be. Also, the more instances of a category we can recall, the larger we believe the category to be. That is, we assess the frequency of instances in a category by how easily we can personally recall instances of it. For example, if we can easily retrieve multiple examples of criminal behavior by immigrants, we believe those instances to be highly frequent. If we have trouble retrieving examples of criminal behavior by toddlers or by centenarians, we believe those instances to be rare.

As with other heuristics and mental shortcuts, we often try to answer a tough question (e.g., “How frequently does this event occur?”) by substituting a much easier question and answering it instead (e.g., “How easily can I recall examples of this event occurring?”). Several factors increase the availability of a given event or category:

- salient and attention-getting events (e.g., sex scandals)

- dramatic events (e.g., violent crimes, terrorist acts)

- personal experiences (e.g., your own participation in an event or your own thoughts or actions involving a category)

- vivid examples, rather than dull data (e.g., an emotionally charged anecdote, rather than a set of statistics)

- pictures, videos, images, rather than numbers or words

So, given the availability heuristic, we are much more likely to overestimate the frequency of events involving attention-getting, dramatic anecdotes about someone we can relate to, especially if we have seen images related to the events. In contrast, we are likely to underestimate the frequency of events (and persons) with which we haven’t had any experience, based on mundane statistical data not associated with any visual images.

The availability heuristic also explains why each spouse, each roommate, and each coworker feels sure that she or he is contributing more to the work of the household or the workplace, as compared with the contributions by the other spouse, roommates, or coworkers: I am 100% aware of each of my contributions during each moment that I do so. I notice every single contribution I make, and I can easily recall each contribution. However, even if I occasionally notice the contributions made by others, I’m less easily able to recall those contributions, and I’m unlikely to be fully aware of each and every contribution made by someone else. Each of us may feel that we’re contributing more than 50% of the work — perhaps much more than 50% — yet somehow, the total contributions don’t exceed 100%. Kahneman cautioned, “You will occasionally do more than your share, but it is useful to know that you are likely to have that feeling even when each member of the team feels the same way” (p. 131).

When we’re asked to recall instances of our own behavior, the ease with which we recall those instances will affect our self-perception much more than the number of instances we can recall.

When we easily come up with a few examples, using the availability heuristic, we believe that the category — or experience or event — is highly common, more likely to occur. If we are then urged to come up with additional examples, we must exert extra cognitive effort to think of more examples of instances or of events. Paradoxically, when we must try harder to come up with additional examples, we then believe the instances are less common or the events are less likely to occur. That is, the degree of cognitive effort seems inversely related to estimated frequency. If we work harder to recall more examples, we assume that the actual frequency of the examples must be fewer. If we can recall several examples quickly and easily, we assume that the actual frequency is much higher. This change in judging the frequency of an event or a category arises because we don’t realize how much more difficult it is to recall additional examples after recalling the first few instances.

Our use of the availability heuristic becomes more likely when

- We are feeling powerful (and therefore feel more confident in our System 1 answers)

- We are feeling in a good mood (and score low on a depression scale)

- We are knowledgeable novices, rather than actual experts about the information

- We have a lot of faith in our own intuition

- We are simultaneously focusing our attention on another task requiring effort

How can we avoid applying the availability heuristic in situations where it makes a difference? If we’re highly motivated to use reasoning, we’ll be willing to make the effort to reason, rather than just go along with using the availability heuristic. We’re more likely to use effortful reasoning when we’re highly interested in finding an accurate answer.

13. Availability, Emotion, and Risk, 137–145

The availability heuristic and disasters: If a particular kind of disaster has been recent, we prepare, and we are vigilantly anticipating a future disaster. The memories of the disaster are recent, vivid, and easily recalled. As time passes, however, these memories become less easily recalled, and our vigilance and preparedness diminish. If we do anticipate disasters, we expect them to be of comparable intensity or of lesser intensity; we don’t anticipate future disasters to be of greater intensity than past ones.

The media play into our misunderstandings of the likelihood of disasters. The media (naturally!) highlight unusual events, especially those that cause deaths. We therefore see and hear more about these unusual events, making them much more available for retrieval than more common events, about which we hear or see very little. As a result, we perceive these unusual events as occurring far more commonly and frequently than is actually the case. Here are some surprising statistics Kahneman cites:

- People are 20 times more likely to be killed by asthma than by tornadoes.

- Strokes kill 2 times as many people as all accidents combined; diabetes kills 4 times more people than accidents do; and diseases cause 18 times more deaths than accidents.

When asked, most people chose the more likely causes as being less likely, and sometimes by a wide margin.

A related heuristic is the affect heuristic, by which people make choices and judgments based on their emotions, rather than reasoning. Instead of asking ourselves, “What do I think about X?” we ask ourselves, “How do I feel about X?” This effect can be particularly troublesome when our feelings about X are impaired or distorted in some way.

The affect heuristic can often be observed by how people respond to a particular kind of technology: “Do I like it?” If so, I’ll positively exaggerate the potential benefits of it and deemphasize the potential risks. “Do I hate it?” If so, I’ll exaggerate the potential risks and deemphasize the potential benefits.

Regarding the affect heuristic, Kahneman quotes Jonathan Haidt as saying, “The emotional tail wags the rational dog” (p. 140).

When using heuristics, we let emotion guide us, rather than reason; we pay more attention to trivial or irrelevant details than to relevant data; and we overrate the importance of low-probability outcomes and events. When government agencies yield to public pressure in assessing risks (or costs) and benefits, all of us are affected.

A related heuristic is the availability cascade, in which “a self-sustaining chain of events” gains media attention, such as self-perpetuating media cycles about the immigrant invasion, or the crime crisis, even in the absence of anything more than scattered anecdotes. Because one publicized event triggers another, these events are perpetually available in the minds of those who follow these media.

As Kahneman said, in considering frequency, we pay more attention to the numerator and less attention to the denominator, so 200 in a million sounds alarming, whereas 1 in 200 sounds less concerning.

“Even in countries that have been targets of intensive terror campaigns, . . . , the weekly number of casualties almost never came close to the number of traffic deaths” (p. 144).

14. Tom W’s Specialty, 146–155

When we don’t have any specific information, we look to what we know about base rates about the likelihood of things, such as which graduate specialty an unknown student is likely to choose. If, instead, we’re presented with a description of the unknown person, we may look for information about the person, which is associated with stereotypes we hold about particularly graduate specialties (e.g., bookishness, library sciences; orderliness and precision, engineering; people oriented, humanities or social sciences or even medicine). We focus on how well the specialty represents our stereotype, and how well the stereotype represents the description of the person.

Hence, when we know absolutely nothing about someone, we fall back on considering the base-rate likelihood of a person choosing various graduate specialties. If we’re given more information about the person, we tend to ignore the base-rate likelihood entirely, focusing instead on how much the description of the person seems to represent a given graduate specialty. This is known as the representativeness heuristic. When asked the likelihood of a particular person choosing a particular specialty, we ignore the difficult task of figuring out probabilities and instead engage in the much easier task of figuring out how well the person’s description seems to represent our stereotype of a given specialty.

It turns out that the representative heuristic sometimes does have a better-than-chance likelihood of producing the right answer, but it’s not as accurate as an answer reached by using base-rate information. Unfortunately, this heuristic can also lead to wildly inaccurate answers unless base-rate information is considered, as well. When in a situation where the representative heuristic may come into play, pause a moment to think about base-rate information. Is a tall, lean athletic young man more likely to be a professional basketball player or a nurse? What do you think?

Kahneman points out the usefulness of being aware of Bayesian statistics. “Bayes’s rule specifies how prior beliefs . . . should be combined with the diagnosticity of the evidence, the degree to which it favors the hypothesis over the alternative. . . . There are two ideas to keep in mind about Bayesian reasoning . . . . The first is that base rates matter, even in the presence of evidence about the case in hand. . . . The second is that intuitive impressions of the diagnosticity of evidence are often exaggerated” (p. 154). Because we tend to think WYSIATI (what you see is all there is) and to believe the coherent stories we make up, it’s easy to make mistakes.

To apply Bayesian reasoning (even without worrying about the mathematical statistical details),

- Focus on a plausible base rate for the probability of an outcome, then use that rate as an anchor for your own guess regarding probability.

- Question whether the evidence you’re seeing is actually helpful in finding an answer.

Also, give yourself a break if you don’t find it easy to use Bayesian reasoning. Kahneman himself said, “even now I find it unnatural to do so” (p. 154).

15. Linda: Less Is More, 156–165

In the conjunction fallacy, we judge the conjunction of two events as being more likely than either of the events alone. We can clearly see the fallacy when asked whether it’s more likely that someone

- has blue eyes,

- is tall,

- is tall and has blue eyes

It seems obvious that being tall and having blue eyes must be less likely. However, this fallacy is harder to avoid when it fits with our other beliefs. For instance, suppose that Linda was a student activist in her college years and even helped to organize some protest marches. After college, is it more likely that Linda

- is active in social-justice organizations

- teaches elementary school

- is a bank teller

- works in a bookstore

- is a bank teller and is active in social-justice organizations

Rank the likelihood of each of these options.

Even though you were aware of the conjunction fallacy, didn’t it seem more likely that Linda “is a bank teller and is active in social-justice organizations” than that she “is a bank teller”? All of us fall prey to this fallacy. When renowned naturalist Stephen Jay Gould read Kahneman’s description of the conjunction fallacy, he said he knew the correct answer, of course, but he still felt intuitively, “but she can’t just be a bank teller; read the description” of Linda (p. 159).

We know intuitively that it’s more plausible that Linda is active in social-justice organizations, and the notion of her being an activist is more coherent with the other information we have about Linda. Even though it’s statistically less probable that Linda “is a bank teller and is active in social-justice organizations,” it just feels intuitively more likely.

Kahneman gives another example of two predictions:

- More than 1,000 people will drown in a flood somewhere in North America next year.

- In California, an earthquake will cause a flood in which more than 1,000 people drown next year.

The second prediction seems more real, more believable, though it is actually less likely to occur. Adding details to a scenario increases its believability, but it actually decreases its probability of occurring.

Along the same lines, people were offered two sets of dishes: a set of 40 dishes, which included 9 broken pieces, or a set of 24 pieces, all intact. If they were offered both sets at the same time, they evaluated the larger set as more valuable. However, when people were offered just one set or the other, the average price earned for the larger set, containing some broken pieces, was lower than the price offered for the smaller set of all intact pieces. The set with fewer pieces garnered more money. The same thing happened when selling sets of baseball cards. When a set of 10 high-value cards were sold, the set was seen as more valuable than a set of 13 cards — 10 high-value cards with 3 moderate-value cards. How does this happen? When System 1 assesses the sets, it readily figures out the average value of each set, rather than summing the total value of each set.

When trying to discredit a proposition, one approach is to raise doubts about the strongest argument for the proposition; the other is to focus more on the weakest argument for the proposition.

16. Causes Trump Statistics, 166–174

When we have specific information about a given case, we tend not to give much consideration to statistical base rates, but we will pay more attention to causal base rates. For instance, when figuring out the likelihood that a hit-and-run driver was over age 65, we may pay little attention to a statistical base rate (e.g., What proportion of drivers are over age 65?). Nonetheless, we may pay more attention to causal base rates (e.g., What proportion of car accidents are caused by drivers over age 65?). Causal base rates are often linked to stereotypes.

System 1 uses categories to organize information in light of norms and prototypical exemplars. Once we have formed a category, we come up with normative examples that represent the category. If the category is a social category (e.g., teenager, grandmother), the normative representation is called a stereotype. Some stereotypes are positive, some are negative, some are mostly true, some are mostly false. Problems arise when we presume that particular individuals should conform to our stereotype for the social category to which the individual belongs.

Kahneman describes an experiment in which 5 study participants were placed in individual booths, with a live microphone passed from one participant to another in the booths. The 5 participants were led to believe that a sixth participant was having a seizure and pleaded for help. Of the 15 total participants, only 4 responded immediately, another 5 responded after repeated calls, and 6 never responded at all. That is, only 27% of participants responded immediately to help.

Other students were told of this study and were shown a video of two individuals participating in the study, up to the point where they were asked for help. When the second set of students were asked to guess the likelihood that the videorecorded individuals would have immediately responded to help, they still believed that they were highly likely to help. Despite knowing that the likelihood was only 27%, they continued to hold their belief that other individuals would help. Their knowledge of the experimental results didn’t affect their view of how they or other people would respond in that situation. “There is a deep gap between our thinking about statistics and our thinking about individual cases. . . . even compelling causal statistics will not change long-held beliefs or beliefs rooted in personal experience” (p. 174).

17. Regression to the Mean, 175–184

“An important principle of skill training: rewards for improved performance work better than punishment of mistakes” (p. 175). Something else that trainers must bear in mind is regression to the mean. That is, when observing a series of performances, an outstandingly good performance is likely to be followed by a less impressive one; likewise, an appallingly bad performance is likely to be followed by a better one. There are inevitable chance fluctuations in performance, with some far superior to the mean and some inferior to it. Regardless of other factors, a poor performance is typically followed by a better one, and a good performance usually precedes a poorer one.

Kahneman’s “favorite equations” (pp. 176–177):

- success = talent + luck

- great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

The more extreme (good or bad) a given performance (or score on a game or test) is, the more likely it is to regress to the mean (the average performance or score). “Regression effects are ubiquitous” and don’t really have a causal explanation (p. 178). Luck/chance plays a role in these extreme performances, so it’s highly likely that subsequent (and preceding) performances will be less extreme. Chance favors regression to the mean over a series of performances (or scores).

Francis Galton (Charles Darwin’s half-cousin) first wrote about regression to the mean when observing the growth of seeds and the height of parents and their children in successive generations. An extraordinarily tall seedling or parent was likely to have a shorter seedling or child; an extraordinarily short seedling or parent was likely to have a taller seedling or child.

Galton went on to consider the interplay of correlation and regression to the mean. (The correlation between your height in centimeters and your height in inches is 1; the correlation between the last four digits of your phone number and your monthly income is 0. “The correlation between income and education level in the United States is approximately 0.40” p. 181.) Even when two things are highly correlated, that doesn’t mean there’s a causal link between them. We often mistakenly attribute causation to coincidences that are merely correlations.

For instance, the husband of an extremely wealthy woman is likely to be less wealthy than she is; the wife of an extremely intelligent man is likely to be less intelligent than he is. The extremely wealthy wife didn’t seek a less-wealthy husband; rather, it’s just more likely that her spouse would be closer to the mean in terms of wealth. Similarly, the highly intelligent husband didn’t particularly look for a less-intelligent wife, but it’s just more likely that his wife would be closer to the mean in terms of intelligence. In our minds, however, we seek causal explanations for these regressions to the mean, such as, “She wanted to feel more generous,” or “He wanted to avoid having her outshine him.”

In assessing treatments for diseases, disorders, or other problems, it’s difficult to differentiate improvement from simply regression to the mean. A depressed or ill person is likely to feel better over time. That’s why it’s crucial to have a control group that receives a placebo treatment in order to assess whether the treatment is effective or the person is simply improving due to regression to the mean.

18. Taming Intuitive Predictions, 185–195

In our lives, we are often in situations calling for us to make predictions: What will be the weather during my outing? How will my friend respond to my offer? How much will it cost to undertake a home improvement? How much time will it take to complete this project?

For some predictions, we can consult resources to improve our accuracy. For many, however, we rely on our intuition, using System 1. In situations where we have repeated experiences and expertise, our intuition, using System 1, will be fairly accurate. Experts in many fields of endeavor have reliable intuition based on extensive practice and research. Most of the time, however, for most of us, we rely on System 1’s intuition based on heuristics and other cognitive shortcuts. When presented with a difficult question, we seek an alternative easy question and answer it instead.

Though we readily reject obviously irrelevant or false information when trying to answer a question, we’re less willing to ignore information that seems to be somewhat associated with the answer we seek. We retrieve readily available information associated with the question and use WYSIATI (what you see is all there is) without looking for more relevant information. We may then evaluate that available information in terms of how it fits with relevant norms. Then we use this information to substitute for the information that would actually answer the initial question.

When making predictions about a probable outcome, we overestimate information about the current situation and underestimate how a regression to the mean may affect a future situation. To compensate for this tendency, when making predictions, Kahneman suggests that you first determine the base rate, or the average outcome for what you’re predicting. Then go ahead and make your intuitive prediction. Then moderate your intuitive prediction, using the base rate, or average outcome.

“Correcting your intuitive predictions is a task for System 2” (p. 192). To make these corrections, you’ll need to go to the trouble of

- Finding a relevant reference category

- Estimating the baseline prediction

- Evaluating the quality of the evidence for the prediction

That requires a lot of effort, so you probably won’t do it most of the time. When the stakes for a given prediction are high, though, and the cost of mistakes are high, it’s worth it to go to this trouble. “Following our intuitions is more natural and somehow more pleasant, than acting against them” (p. 194). Even when we’re aware of regression to the mean, it’s often easier to come up with false causal explanations for random fluctuations toward the mean.

Figure 04. These are the contents discussed in Part 1 of my 3 blogs about Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Part 2 will be posted June 24. Part 3 will be forthcoming after both of my eyes have recovered from cataract surgery well enough to read and write.

Copyright © 2025, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment