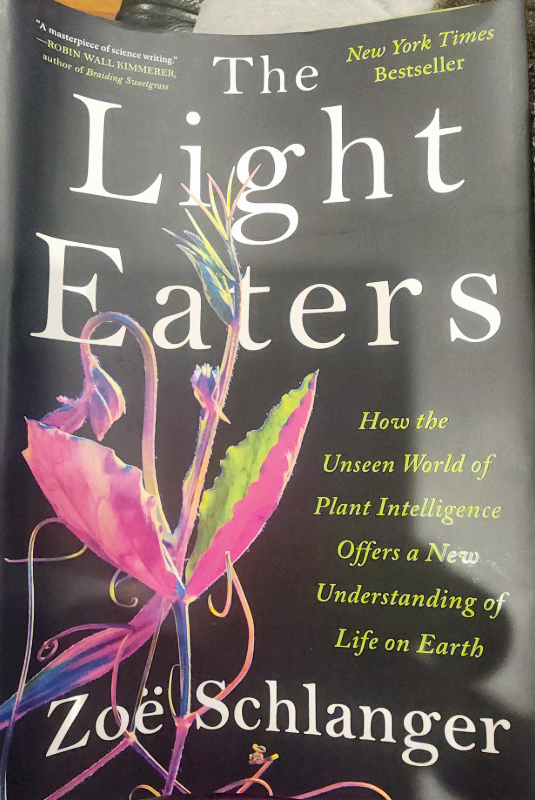

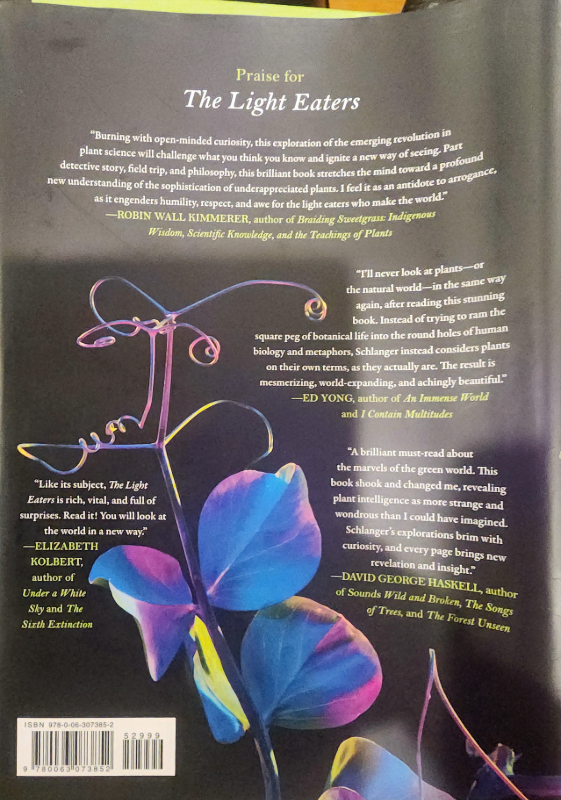

Zoë Schlanger. (2024). The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth. NY: HarperCollins.

Schlanger passionately cares for plants, having devoted years to researching and writing this tribute to plants, which she shows to be adaptive, creative, fascinating, surprising, and delightful, as well as vital to human survival and to the survival of life on Earth.

A journalist by trade, Schlanger thoroughly investigated numerous aspects of plant research, traveling the world to interview botanists and visit amazing plants in the field.

Suggestions for improvement: I would have liked a dedicated references or bibliography section, but her notes indicate where she found her information. Her index is better than many, but not as complete as I would have hoped in my ideal wish list.

- Prologue, 1–6

- Chapter 1. The Question of Plant Consciousness, 7–24

- Chapter 2. How Science Changes Its Mind, 25–51

- Chapter 3. The Communicating Plant, 52–74

- Chapter 4. Alive to Feeling, 75–100

- Chapter 5. An Ear to the Ground, 101–118

- Chapter 6. The (Plant) Body Keeps the Score, 119–136

- Chapter 7. Conversations with Animals, 137–157

- Chapter 8. The Scientist and the Chameleon Vine, 158–192

- Chapter 9. The Social Life of Plants, 193–214

- Chapter 10. Inheritance, 215–239

- Chapter 11. Plant Futures, 240–259

- Acknowledgments, 261–263

- Notes, 265–280

- Index 281–290

- About the Author, 291

Prologue, 1–6

In her prologue, Schlanger introduces us to some of the complexity in the lives of plants. Most flowering plants require pollinators, such as butterflies, to reproduce. Yet an overabundance of caterpillars — larval butterflies — can kill a flowering plant. How can a plant minimize the harm from caterpillars, such as by releasing harmful or at least unappetizing chemicals into its leaves, while ensuring that enough caterpillars survive to become butterflies that will ensure its propagation into future generations?

Figure 02. This plant welcomes having this Postman butterfly pollinate its flowers, but if too many of its leaves are eaten by larval butterflies (caterpillars), it’s in grave peril.

While almost all plants lack any locomotion abilities — they’re literally rooted — they do move, albeit slowly. To move, they must grow in the desired direction, so they make big investments — and take big risks — in choosing where (and when and how) to grow. If they invest their resources into moving into an area lacking adequate sun, water, or nutrients, they lose big.

Schlanger acknowledges the often-heated controversies about whether plants are “intelligent,” but she also points out that all — or nearly all — botanists marvel at the amazing and often surprising capabilities of plants.

To hint at the depth of her admiration, she says plants “suffuse our atmosphere with the oxygen we breathe, and they quite literally build our bodies out of sugars they spin from sunlight. . . . They have complex, dynamic lives of their own — social lives, sex lives, and a whole suite of subtle sensory appreciations . . . . they sense things we can’t even imagine, and occupy a world of information we can’t see” (p. 5).

Chapter 1. The Question of Plant Consciousness, 7–24

Schlanger has a special fondness for ferns, “being extremely ancient, [with] up to 720 pairs of chromosomes, versus humans’ mere 23” (p. 9). More ancient than flowering plants, ferns reproduce without seeds. During extreme drought, resurrection ferns can dehydrate almost entirely and stay dehydrated for more than 100 years — then get adequate water and fully rehydrate. Ferns can also remotely mess up neighboring ferns’ reproduction, by releasing hormones.

About 50 million years ago, “when the earth was a much warmer place, [Azolla filiculoides, one of the world’s smallest ferns] began growing over the Arctic Ocean in vast fern blankets,” spending the next million years absorbing so much CO2 that it may have played a key role in cooling Earth. “Some researchers are looking into whether they could help do that again” (p. 9). WOW!

Azolla has another trick, too. Plants need nitrogen to photosynthesize, and although nitrogen composes almost 80% of the air we breathe, it’s completely inaccessible to plants and animals without help. Azolla (like many other plants) hosts and cultivates cyanobacteria, feeding them sugars; in turn, the cyanobacteria make nitrogen available to the fern.

Renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks was also a huge fan of ferns. Schlanger celebrates many naturalists and plant admirers, such as Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), explorer who promoted the concept of viewing nature through an ecological lens.

Many plants can not only distinguish themselves from other plants, but also figure out whether neighboring plants are genetic kin. When near genetic kin, they show plant etiquette, arranging their leaves to avoid shading their kin. Plants can also minimize harm from hungry predators — such as by secreting distasteful chemicals or even by releasing volatile compounds (carried through the air) that attract predators known to eat the hungry plant eaters.

Figure 03. Can this borage recognize its kin? Is it showing plant etiquette toward its neighbors?

Trying to understand plants’ behavior can be deeply challenging: “Researchers . . . found that plants could remember, but not where those memories are stored. They’d found kin recognition, but not how those kin are recognized” (p. 23).

“Nature is chaos in motion. Biological life is a spiraling diffusion of possibilities” (p. 21).

Chapter 2. How Science Changes Its Mind, 25–51

Life on Earth: “A billion and a half years ago, an alga-like cell swallowed a [cyanobacterium]. That alga-like cell was the early organism from which both animals and fungi would later evolve, and the cyanobacteria is an ancestor of the unthinkably diverse bacteria that flood our world today. But together they were the start of a new branch of life entirely. . . . this single sentinel of a new kingdom began to photosynthesize. It took sunlight, and alchemized the spare materials of its environment—water, carbon dioxide, maybe a few trace minerals—into sugar. . . . A billion and a half years [later], plants have evolved and proliferated into a half million species that thrive in every ecosystem on the planet. . . . If weighed, plants would amount to 80 percent of Earth’s living matter” (p. 26).

When plants emerged, Earth’s air was mostly a “fog of carbon dioxide and hydrogen” (p. 26). Plants single-handedly oxygenated Earth’s air, making Earth habitable by the beings alive today. What’s more, “plants have made every iota of sugar we have ever consumed. A leaf is the only thing in our known world that can manufacture sugar out of materials—light and air—that have never been alive” (p. 27).

How does it work? Basically, the tops of leaves absorb energy from sunlight. Beneath each leaf, stomata (lip-like pores) “inhale” carbon dioxide (CO2) from the air. The leaf separates out the needed carbon (C), combines it with water and some key nutrients obtained by the roots, and transforms it into carbon-based sugars. The stomata then “exhale” the leftover oxygen (O2). Magic! According to Schlanger, “it takes six molecules of carbon dioxide and six molecules of water, torn apart by power from the sun, to form six molecules of oxygen and—the true aim of this whole process—one precious molecule of glucose” (p. 27).

In Schlanger’s view, plants have shown remarkable “innovation, adaption, and luck” in colonizing all of Earth’s continents (p. 28). One of the strategies used is adaptive radiation, by which wayward seeds arrive in a new location (carried by wind? waves? bird feathers?) then transform themselves to adapt to the new location. Over time, the new arrival transforms itself into one or more new species well suited to the new location.

“Seeds are embryos encased in nutrients,” ready to grow into a mature plant. Choosing when and where to begin to grow means taking a huge risk. If the seed grows in an unfavorable location, at an unfavorable time, it will have blown all its nutrients — and any hope of living — on a lost cause. Often, seeds allow themselves to be tossed around for many years, waiting for the right place and time to implant. By sending down its first root, it risks its only chance at life. “The baby plant has [48] hours after it . . . [emerges] to locate water and nutrients, and then push out a leaf or two and begin photosynthesizing, before it runs out of resources and dies. . . . Any given seed has a vanishingly small chance of making it into its full plant form” (p. 31).

Figure 04. If these cherry seeds are planted, how will they know when to emerge to begin new life as a cherry tree?

Once established, “plants are . . . synthetic chemists,” making an array of repellents, attractants, hormones, toxins, weapons, anesthetics, and more (p. 32). Perhaps most important, a plant can produce chemical signals for other parts of the plant to boost its immune system or to take other actions.

Often, the most dangerous enemies of plants are other plants. On islands where plants evolved to fit perfectly into their isolated ecosystem, introduced invasive plants threaten to overtake the natives, unable to adapt quickly enough to prevent being extinguished.

When discussing how humans have viewed plants throughout history, Schlanger noted that some — such as Aristotle and Descartes — deprecated plants as insensate and unintelligent, whereas others, such as Theophrastus, have carefully studied plants, appreciating their adaptations and behavior. Theophrastus saw many similarities between plants and people, even suggesting that agriculture should be viewed as a collaborative relationship between plants and humans. Schlanger also highlighted the insights of scientists such as William Harvey (who described blood circulation), Charles Darwin (evolutionary natural selection), and Donald Griffin (who discovered bats’ echolocation). She underscored the challenges of shifting scientific paradigms and the inherent conservatism of scientific progress.

Though plants lack brains and neural systems, they do produce and sense chemicals used as neurotransmitters in animals. Figuring out plant “neurobiology” will require deep investigation, as well as openness to new ideas.

Chapter 3. The Communicating Plant, 52–74

Plants often communicate via scents sent to other plants, to animals (e.g., potential pollinators), or to other forms of life.

Zoologist and organic chemist (and entomologist) David Rhoades watched what happened in trees that were undergoing an invasion of hungry caterpillars. For several years, the caterpillars were wiping out many trees in a devastating assault. The caterpillars ate all the leaves, which therefore couldn’t produce sugars, effectively starving the trees to death.

Figure 05. Though butterflies are vital to the reproduction of flowering plants, an invasion of hungry caterpillars can be devastating to plants.

Then somehow, the tide turned. The caterpillars were starting to die on the trees, and soon the caterpillars were dying in large numbers. The dying trees were somehow warning other trees of the invasion. The forewarned trees were able to mount a chemical defense against the caterpillars, who would get sick and die after trying to eat those trees’ leaves. Within about a year, the assault had ended. At first, botanists had thought the communication occurred via the trees’ roots, but the forewarned trees were foo far away to receive signals through their roots. Instead, the dying trees were releasing volatile (airborne) compounds to warn other trees of the invasion.

Communication also occurs within a plant, such as when a seed is deciding whether to emerge from its protective case. Cells within the seed gather information about the environment — temperature, moisture, and so on — accumulate and integrate that information, and then collectively decide when the conditions are right for emerging.

One of my favorite quotes: “The scent of cut grass is the chemical equivalent of a plant’s scream” (p. 60).

Giraffes, kudus, and acacias: “When acacias begin to be eaten, they increase the bitter tannin in their leaves. . . . At first, the tannin rises just a little. It’s not dangerous, but it tastes bad.” However, if the leaves are still being eaten in large numbers, “the acacias [deliver] a lethal dose” of tannin (p. 62). What’s more, the trees being attacked release volatile compounds that warn neighboring trees, so they, too, boost their tannin levels before being overeaten. Giraffes carefully choose how many leaves to eat from which trees, to avoid getting toxic doses of tannin, but kudus overpopulating a kudu ranch couldn’t avoid eating lethal doses of acacia leaves, so they died in large numbers.

In conditions of mild threat, some plants may send warnings just to closely related plants of their own species. When the threat is more dangerous, however, they may send more global warnings, easily received and understood by all neighboring plants. Why? It’s thought that in dangerous situations, it’s advantageous to have all your neighbors able to defend against the threat, so you’ll still enjoy the benefits of being in a community, such as attracting numerous pollinators.

Plants also have differing levels of risk aversion, with some individuals highly averse and others less so. The same goes for aggressive behavior (e.g., climbing higher, spreading more widely, making bigger leaves). Biodiversity includes diversity of “personality” attributes, such that a given ecosystem benefits from having both risk-taking and risk-averse plants.

Modern agriculture values crop yield above all else, and monoculture crops are typically bred to be as productive as possible. But this kind of breeding neglects other characteristics, such as a plant’s ability to defend itself against insect pests or other assaults. Because farmers have (unwittingly) bred out the plants’ ability to defend themselves, the farmers end up using huge amounts of pesticides, fertilizers, and other additives to sustain these monoculture crops. This short-sightedness not only increases pollution and decreases resilience, but it may also end up decreasing productivity. “Research has . . . shown the benefits of biodiversity to the resilience of a farm field or an ecosystem” (p. 74).

Chapter 4. Alive to Feeling, 75–100

In the human body, the cell membranes of our resting cells are slightly negatively charged. In the plasma between those cells, our electrolytes — sodium, magnesium, potassium, and calcium ions — are positively charged elements. When our cells are touched, the membranes open channels and let the ions pass through the membranes. Once those electrolytes pass into the cells, the cell switches from being negatively charged to being positively charged, which also triggers neighboring cells to switch their charges. “This chain reaction travels fast, sending information via the electric current that the bestirred cells made . . . to your brain and back again” (p. 76). Nearly all of our cells have this potential for generating electricity, such as our muscles (when they contract or expand). The smooth muscles that surround our veins likewise expand and contract to move blood through our bodies.

Anesthesia diminishes the electrical transmission to and from our brains. Interestingly, plants also conduct electricity through their cells; when they’re anesthetized, they, too, diminish their electrical activity.

Figure 06. Would it be possible to detect electrical transmissions within this borage bush?

Through thigmomorphogenesis, plants respond to touch, even changing their growth patterns when touched. Different plants respond in different ways when touched, but all respond somehow, at least somewhat. For instance, some trees grew stouter and harder after repeated touches; some wax beans grew more elastic; some plants inhibited their growth. It’s thought that a possible mechanism for this is that repeated touch activates the plant’s immune system, which responds defensively in ways suited to that plant in that environment.

Jagadish Chandra (J. C.) Bose (1858–1937) — an Indian botanist, biologist, physicist, and science-fiction writer — pioneered in wireless telecommunication, but he also studied electrical communication within plants. His observations led him to conclude that “electrical impulses were responsible for controlling most plant functions, [such as] growth, photosynthesis, movement, and responses to whatever the environment threw their way — light, heat, exposure to toxins” (p. 82).

In the 1990s, Barbara Pickard and her team discovered that plant cells had “gates” to allow electrical currents (via calcium ions) to pass through them when they were physically touched — mechanosensitivity. The process differs in plants, compared with animals, but the electrical communication occurs nonetheless. Colleagues didn’t welcome the conclusions drawn by Pickard and others, funding dried up, and her research languished.

Decades later, newer technology has made it cheaper and easier to study electrical activity in plants. Almost anyone can detect electrical activity in plants now. One of the easiest observations was how electrical activity is involved when Venus flytrap leaves respond to being triggered to snap shut around prey.

Observations are increasingly revealing that plants have agency — they affect their environments in ways to make their surroundings more habitable to the plants. Botanists still have little understanding about how plants do so. For instance, it’s clear that plants can detect gravity, but it’s not clear how the mechanism that detects gravity can communicate that to the roots that grow toward gravity and the shoots that grow in the opposite direction.

Figure 07. “Biotic creativity is our inheritance . . . . Life finds a way, if given a chance” (p. 258).

Humans use glutamate as a neurotransmitter; glutamate is also involved in transmissions within plants. Botanists have been able to track the movement of glutamate through the veins of a plant by using bioluminescent proteins. They were able to watch glutamate’s illuminated movement as the plant responded to being wounded (cut or pinched). Within two minutes, the whole plant had received the transmission. How does that happen? Plants have no neurons, no neural synapses, and no brains.

Chapter 5. An Ear to the Ground, 101–118

Two flowering vines, Marcgravia evenia and Mucuna holtonii, have developed different strategies for attracting their bat pollinators only when they have their pollen ready to dust the bats. Both vines can make themselves acoustically tuned to the bats’ echolocation senses. One vine has a circle of flowers inside a series of oblong, concave glossy leaves, which perfectly reflect the bat’s echo from multiple angles when the flowers have pollen ready to dust the bat as it laps up the nectar. The other releases an explosion of pollen onto the bat’s rump when the bat lands on the flower and forcefully presses its snout between two flower petals. The bats completely ignored these flowers when the flowers weren’t prepared to release more pollen. The flowers had become acoustically silent until they were ready with more pollen to release.

Acoustics also play a role in how a plant can defend itself from being devoured. Apparently, plants can somehow sense the vibrating sounds of caterpillars chewing their leaves. As soon as plants detect that sound, they produce insect repellents or foul-tasting compounds (e.g., bitter tannins), which deter caterpillars from approaching the plant or at least stop the caterpillars from eating more. To make sure that it was the sound that produced the response, experimenters simply produced the sound of the caterpillar’s chewing, in the absence of actual caterpillars, and the plants responded just the same. Thus started the field of phytoacoustics — plant detection of sounds.

Figure 08. Is this Monarch butterfly making any sounds this Lantana flower can sense?

If artificial sounds could get plants to produce their own pesticides and pest repellents, could that be used to help farm crops create their own defenses, without the need for synthetic pesticides? Preliminary studies say “yes.” They have also succeeded in nudging plants to produce more nutrients, such as higher levels of flavonoids and of Vitamin C. Other possibilities: the sound of bees buzzing to prompt the release of pollen or the sweetening of flower nectar, the sound of frugivores to nudge ripening of fruit, the sound of distant thunder to prepare for receiving rain?

Some plants seem especially primed for sound; for instance, some flowers are shaped perfectly to amplify the sounds at the frequency of their pollinators. Plant roots may also be primed for sound, responding to the sounds of moving water. (Plumbers and city planners are particularly unhappy with the way that large tree roots seem to find their way to distant water pipes.)

Plants also communicate to one another regarding availability of water. “Plants emit very quiet clicking noises when air bubbles in their stems pop as water travels up them [in the process of] cavitation, and these ‘cavitation clicks’ seem to increase when plants are dealing with drought stress” (p. 112). In general, each species of plant has a distinctive click frequency, but a drought-stressed plant clicks even more frequently than normal. It’s possible that nearby plants can detect these clicks.

Figure 09. “I’ll never look at plants—or the natural world—in the same way again, after reading this stunning book.” Ed Yong, author of The Immense World

Scientists are just beginning to understand how songbirds and prairie dogs use sound to communicate to one another, emitting particular sounds to convey particular meanings. Perhaps with more study, botanists will begin to understand plant “syntax” and “vocabulary.” “No one is disputing that plants can actually hear. What they are listening for, . . . remains to be fully determined” (p. 118).

One other interesting idea: Plants’ clicks (similar to bats’ echolocation clicks) may help to sense more than the experiences of other plants. Perhaps vines can use clicks as a kind of echolocation to find supports. Vines circumnutate as they grow upward, making increasingly wider rotations until they find a support to which they can cling and then grow. Perhaps echolocation helps some plants during this process.

Chapter 6. The (Plant) Body Keeps the Score, 119–136

It takes energy and resources for plants to produce nectar and pollen. They must be prudent in parceling out nectar and pollen because if they release too much to one particular pollinator, they limit where their pollen will go, thereby limiting their reproductive spread. It’s better to distribute a little at a time, to various pollinators. For instance, when a flowering plant (Nasa poissoniana) senses few pollinators are in the area, it increases the quantity of pollen it releases, to give each pollinator more pollen; when more pollinators are near, it’s stingier with its pollen. It also boosts the quality of the nectar when there are fewer pollinators and lessens the quality when pollinators are abundant.

This plant also senses when a bee is sipping its nectar and erects its pollen-filled stamen then. It also seems to sense time and to remember time intervals between visits by pollinators. It senses how long it’s been since a bumblebee has visited it and seems to anticipate when it’s likely to visit again, so it can be prepared with nectar and pollen at the right time. Experimenters wondered where the plant is storing these memories. They wondered whether plants, like octopuses, store memories throughout their bodies, not just in one particular central location or specific structure. Human immune systems do so, too. We store memories of pathogens throughout our cells.

Figure 10. Is this salvia flower anticipating a visit from a pollinator?

Other evidence of plant memory appears in mallow plants, which follow the sun throughout the day, and then — overnight, in darkness — they turn toward where they predict that the sun will rise the next morning.

Many plants, such as bulbs (tulips, garlic, hyacinth) and some fruit trees (apples, peaches), must undergo winter freezes in order to sprout up in the spring. This “vernalization” may involve some kind of memory of winter. These plants also seem to know when a warm spell is fleeting or heralds the arrival of spring. They appear to “count” the number of warm days, holding off on a growth spurt until the warm weather has lingered for several days.

One of the most dramatic examples of “counting” occurs with Venus flytraps. If two of its trigger hairs are touched within 20 seconds of each other, the trap snaps closed. But then it waits. It doesn’t go to the trouble of releasing its digestive juices unless its trigger hairs are triggered five more times within a short time. At that time, it goes to the costly expense of secreting digestive juices into the trap. If the trap doesn’t sense five more triggers, it opens again within a day, without wasting its digestive juices.

At their growing tips (above and below ground), plants have meristems, each one a cluster of cells like mammalian stem cells, which can be turned into any kind of cell that the plant needs. These meristems continually monitor how well the entire plant is doing in every part of the plant. The meristems detect where a plant needs more resources, where it needs fewer, and where it’s doing so poorly that it’s better not to waste additional resources on it. During this monitoring, meristems must also remember how the plant has been doing over time. Has a leaf been photosynthesizing less? Is a root finding more nutrients? What’s going on, compared with what was going on?

“As any plant grows, it builds its body to suit its environment, [in both roots and shoots]. The shape that emerges is a direct response to the physical obstacles it encountered, the distribution of nutrients in the soil, and the direction of the light. In this way a plant’s entire body is a physical expression of the conditions, moment to moment, over the whole story of its life” (p. 133).

Chapter 7. Conversations with Animals, 137–157

Consuelo De Moraes observed that corn plants had a distinctive defensive strategy. When caterpillars were chewing this corn plant, the plant “samples the combination of saliva and regurgitant the caterpillar leaves behind on its leaves” and can thereby detect the species of the caterpillar. The plant then produces and releases a particular volatile compound into the air, and “within an hour” after releasing the compound, a particular species of wasp arrives — a wasp that parasitizes this particular species of caterpillar (p. 139). De Moraes has since observed this defensive response in cotton plants and tobacco plants, too. (Could we say that the plant uses the parasitic wasp as a tool for getting rid of the predatory caterpillars?)

Figure 11. This European Starling is eating a leaf-eating caterpillar, but this caterpillar will never become a pollinating butterfly. Is the starling helping or hurting plants?

De Moraes later made an even more astonishing discovery: She noticed bumblebees unable to feed at the closed buds of mustard flowers. The bees were about to starve, when they began to nibble on the plants’ leaves. The very next day, the flowers bloomed, offering nectar to the starving bumblebees. She later experimented and found that “bees biting plants made their flowers bloom as much as [30] days earlier than they would otherwise” (p. 140). A win–win for the flowers and for the bees; flowers spread their pollen, and bees enjoy the nectar.

A particularly nasty way that insects can injure plants is to form galls, lumpy growths in which the insects “hijack the plant’s DNA” to force the plant to build a home for the insects’ eggs inside the plant’s own tissue. Then once the eggs hatch, the larvae voraciously devour the plant that had housed them. When goldenrods sense that gall-forming flies are nearby, they can mount defenses against the flies, releasing volatile compounds that tell the flies the defenses are up, and warning nearby plants to do likewise. When female flies detect the volatile compounds, they go elsewhere to form galls and to lay their eggs.

Quite a few plants (e.g., acacias, bittersweet nightshade) engage ants to help them get rid of insect pests — such as beetles and other species of ants. Botanists call them “ant plants.” Other plants have symbiotic relationships with bacteria, exchanging plant sugars for easy access to nitrogen and other nutrients.

Plants can synthesize a seemingly limitless variety of chemicals, including semiochemicals, “any compound that is synthesized in one body and released to infiltrate another” and affect its behavior (p. 146). Orchids seem to be particularly adept at producing highly specialized semiochemicals, often using them to interact with particular wasps and other insects.

Some plants seem to preferentially bloom together, such as brilliantly violet asters and blazingly yellow goldenrods. Pollinators are especially attracted to flower fields where these two are paired. When they grow next to each other, they both benefit.

Some plants cooperate for mutual defense. For instance, when silver birch trees grow near Rhodendron tomentosum, the birches absorb the smell of the rhodendron, which defends both against a predatory weevil.

Some plants can produce asexually as clones (e.g., aspens, dandelions), some can produce asexually or sexually, some are bisexual (with both male and female parts in one plant), and some only produce sexually as either male or female plants. Surprisingly, an “ancient gingko tree can spontaneously switch the sex of a section of its body, producing a female branch on an otherwise male tree” (p. 151). Plant clones are challenging to contemplate: Are huge clonal colonies just one mega-organism, or are they a community of identical siblings?

Ozone pollution and other kinds of air pollution harm plants and entire ecosystems, stressing all aspects of the ecosystem and all those living within it. Perhaps one more consideration is how air pollution inhibits, distorts, or suppresses plants’ airborne signals via volatile compounds. This suppression may go both ways. The plants sending the signals may have their signals distorted or attenuated, and the plants who would receive the signals may keep their stomata closed more of the time, to minimize the intake of pollutants. If plants can’t signal one another, they can’t warn each other of insect pest attacks. Pollinators, too, rely on those airborne signals, so both pollinators and pollinating plants lose out.

Figure 12. When this salvia petal was eaten, did the plant send out warning signals to other parts of the plant or to neighboring plants?

This communication problem is made worse in monoculture domesticated plant crops, which may already have had some of their communication abilities bred out of them. Domesticated monocultures seem less able to defend themselves, so they rely on farmers to use pesticides and chemical fertilizers, which further add to air and water pollution.

Botanists are trying to encourage farmers to use companion plants (e.g., borage with strawberry plants) with their crops, noting that crop yields may be enhanced by more eco-friendly traditional farming practices.

Chapter 8. The Scientist and the Chameleon Vine, 158–192

Vines have at least four strategies for climbing: coil around vertical objects to climb (e.g., Ceropegia), produce tiny hooks that let them pull themselves upward (e.g., phlox), secrete sticky adhesives for ascending (e.g., Boston Ivy, per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Parthenocissus_tricuspidata), or produce aerial rootlets that cling to whatever they’re climbing (e.g., ivy in the Hedera genus, per https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hedera). With each of these strategies, the vines circumnutated around until they latched onto the support.

As a young pink vine, the Hydrangea serratifolia seeks shade as it slithers along the ground searching for a tree. Not just any tree — it must be a tree big enough to support the vine as it grows for hundreds of years. Once the vine finds a suitable tree, it changes from pink to green, and it seeks sun, instead of shade, climbing up the tree until it reaches sunlight. In full sunlight, the vine blooms, then its seeds fall to the forest floor, where the process is repeated.

Plants have a distinctive relationship with light: Leaves need at least some light, while roots must have as little light as possible, with utter darkness being best. In fact, roots actually flee from light, growing as fast as possible to escape away from it. This rapid growth has misled some botanists to incorrectly believe that light fosters root growth, but it’s actually a strategy to escape away from light.

Plants may be able to sense when sunlight is falling directly on their leaves or is being filtered through the leaves of another plant located above their leaves. Plants have photoreceptors for red light (the light wavelength needed to convert CO2 and H2O into sugars). In addition, they have 13 more “types of light receptors . . . , each of which contribute vital information; some allow a plant’s shoots to grow toward light, and others help it avoid damaging UV rays,” but the functions of most others aren’t yet known (p. 169).

Plants living in places with abundant sunlight can afford “to do costly things like change leaf shape and color and vein pattern,” whereas plants living in rain forests, with varying access to sunlight, “will make small, tough leaves — minimizing their energy use” until they have surer access to sunlight (p. 181).

Among crops, some weeds mimic crops, reducing their chances of being pulled. In fact, oats, as a crop, “got their start by mimicking wheat” (p. 165). “We didn’t domesticate oats; oats domesticated us” (p. 166).

How do plants manage to mimic other plants? Can they somehow “see”? Cyanobacteria, ancient ancestors of plants, “had (and still have) the smallest and oldest example of a camera-like eye” — and plants evolved from the merger of cyanobacteria and an early alga. So it’s not impossible that plants might have some kind of simple eyes. If so, these simple eyes would probably be on the surface of the leaf, just above the location of the chloroplasts that make photosynthesis possible (p. 167). The fact that plants are phototropic, orienting themselves toward sunlight, suggests some ability to sense light.

Figure 13. When this feverfew — wild chamomile — orients itself toward sunlight, how is it sensing light?

Boquila plants have the distinctive ability to mimic the appearance of nearby plants — even the shape, texture, color, and vein pattern of the leaves of nearby plants. When climbing on trees, this vine mimicked the leaves of four different trees. The advantage of doing so is that when their leaves blended in with the surrounding leaves, they were less likely to attract the unwanted attentions of herbivores.

Parasitic mistletoe plants have also been seen to fully mimic the plant they’re parasitizing. Mistletoe that parasitizes eucalyptus looks like eucalyptus; when it parasitizes oak, it looks like oak. The mistletoe, however, has access to the circulatory system of its parasitic host. The boquila doesn’t. It doesn’t even have to have physical contact with a plant it mimics. What’s more, the boquila can mimic a wide array of other plant species (including ferns) — typically, whichever plant is nearest. (When transported from Chile to London, it mimicked not only English species, but also a New Zealand transplant.) The boquila could mimic not only the top surface of a leaf but also spikes or other features on the underside of a leaf. This ability suggests that the boquila detects the other plant’s appearance by means other than just some kind of visual sensations.

Another possible factor in the plasticity of the boquila’s mimicry might be microorganisms, probably bacteria, which guide the leaves to change shape, color, or texture. Perhaps microorganisms do so “by hijacking and redirecting the genes that control leaf shape” (p. 182). Perhaps the boquila is just the tip of the iceberg, and microbes are influencing the appearance of all or most plants.

Microbes in the guts of termites make it possible for termites to digest wood. Microbes in humans “influence our immune systems, our smells, and our attractiveness to mosquitoes,” as well as having many psychological effects. “Our own cells are [probably] outnumbered by our microbial tenants” (p. 186). Our microbiomes are also constantly changing as we move from place to place, contact new people, inhabit new places, even take a shower, as well as ingest different foods or medications.

“The plant and its microbes are [probably] inseparable. They are a composite organism, a tightly fused collaboration.” That’s fitting, given that the earliest ancestors of plants arose when a “photosynthetic [bacterium] came to live within an algae cell” (p. 187).

In 1868, Charles Darwin said, “Each living creature must be looked at as a microcosm — a little universe, formed of a host of self-propagating organisms, inconceivably minute and as numerous as the stars in heaven.’ . . . The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication” (p. 188).

Chapter 9. The Social Life of Plants, 193–214

Many species of animals (naked mole rats, a shrimp species, many ants and bees, some beetles, and at least one aphid) show eusocial behavior, acting to preserve the well-being of the colony above the well-being of the individual. Staghorn ferns seem to show similar behavior, with some ferns directing resources to other ferns, which can then reproduce on behalf of all the ferns on a given tree. Plants vary in their sociability, with some plants appearing to behave individualistically, whereas others appear to live in highly collaborative collectives.

When light passes through a plant leaf, the light is changed slightly, and different plant leaves change the light differently. When plants sense being surrounded by more tall neighbors, they grow their stems longer, taller; when fewer neighbors are near, they grow shorter stems. Below ground, roots also adjust their growth patterns in relation to their neighbors, making more roots if they have more neighbors. Moreover, plants sense when the neighboring plants are genetic kin; they curb their growth near kin, but boost their growth near strangers.

Figure 14. Is this sunflower plant being inhospitable to nearby plants of a different species?

As an example, sunflowers “tilted their stalks at alternating angles to avoid shading their kin-neighbors” (p. 200). Sunflowers also produce more seeds when grown near kin than when grown near strangers. Sunflower roots also show neighborly etiquette. When a nutrient-rich patch of soil is located equidistant between two sunflowers, each plant grows shorter roots in that direction, avoiding direct competition. When a rich patch of soil is slightly nearer to one of them, however, the roots of the nearer one dramatically increase toward the nutrient-rich patch. On the other hand, sunflowers are downright hostile to strangers; their roots secrete chemicals to stop other plant seedlings from germinating.

Flowering plants will work harder to attract pollinators (more flowers, more lavish displays) when growing near kin than when near strangers. It’s not clear exactly how plants recognize their genetic kin. One way they do so is by detecting chemicals transmitted from the roots of one plant to the roots of another. Another way is to discern differences in the characteristics of the light reflected back to them by the leaves of a neighboring plant.

Many carnivorous plants will collaborate to attract and catch larger prey when near other carnivorous plants.

Farmers may unwittingly be breeding crops that produce lower yields by selectively choosing plants for their “vigor,” but breeding out plant cooperation. The competitors strive for height and breadth, but in doing so, they may produce fewer seeds and fruits. If, instead, farmers bred crops for social cooperation, the plants wouldn’t waste energy competing and would instead produce more seeds and fruits.

Figure 15. Is the plant creating these garden-grown blueberries better able to defend itself, and to produce more delicious berries than a plant grown in a monoculture field crop?

Half of each plant lives beneath the ground, with its roots in the rhizosphere — “the world of soil and multitudinous organisms that live below its surface, in and among plants’ roots” (p. 206). Just one teaspoon of soil contains up to 1 billion microbes; the role of these microbes is mostly a mystery yet to be revealed. Somewhat less mysterious is the crucial symbiotic relationship of fungi and plants. Fungi evolved before plants, and plants coevolved with fungi.

Fungi provide essential nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, copper, zinc) to the plant; in exchange, plants photosynthesize sugars vital to the fungi. Fungi also influence many aspects of the plants’ characteristics, such as sweetening the tomatoes and affecting a plant’s aromatic, antioxidant, and medicinal properties.

Plants are much more highly complex than we had previously known, showing “surprisingly adaptive mechanics of their bodies, [with an] ability to precisely respond to their environment” (p. 214).

Chapter 10. Inheritance, 215–239

Some plants don’t need pollinators. Spigelia genuflexa literally bends over and plants its own seeds into soft moss. Peanuts can plant their own seeds, too. The fruits of plants also show adaptations to protect their seeds, such as by lightening or darkening, to reflect or absorb sunlight, in response to air temperature; by thickening the fruit’s protective coats; or by increasing the fruit’s surface area. Parent plants may shade their offspring or offer nourishment to it before the parent dies.

Figure 16. In what ways did the cherry tree nurture its seed-bearing fruits, and what environmental adaptations has the tree passed on to its seeds?

Parent plants also somehow pass many adaptations to their offspring. Parent plants that grow in shade will have offspring better adapted to shade; parent plants that must tolerate drought will have more drought-tolerant offspring. When plants are grown in waterlogged soil, they make numerous adaptations to their roots, to avoid drowning. Interestingly, their offspring emerge with these adaptations to excessive water or to drought. And so do their third-generation descendants.

Health tip: If your family is predisposed to getting lung cancer, you may have a particular gene mutation that predisposes you to lung cancer. If so, if you eat enough broccoli, you can compensate for your genetic predisposition. Broccoli can’t make you immune, but it can compensate for your familial genetic predisposition.

The emerald-green sea slug, Elysia chlorotica, starts out as a brownish slug until it manages “to locate the hairlike strands of the green algae Vaucheria litorea.” Once it finds its alga, “it punctures the alga’s wall and begins to slurp out its cells as though through a straw, leaving the clear tube of empty algae behind” (p. 227). That done, it uses the alga’s chloroplasts to photosynthesize (known as kleptoplasty). From then on, the chloroplasts continue to churn out sugars that sustain the slug. That is, this animal consumes algae, incorporates it, and photosynthesizes, never having to eat again! For a photo of this slug, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elysia_chlorotica

“Everything, at every level from a microbe to a rain forest, . . . is an ecosystem. . . . All biology is ecology” (p. 230).

Many endangered species aren’t very adaptable or “plastic” in modifying themselves to suit their changing environment. Other species — especially invasive species — are highly adaptable and plastic, able to transform themselves seemingly limitlessly.

Chapter 11. Plant Futures, 240–259

“Whether or not plants are intelligent is a social question, not a scientific one” (p. 244). Nonetheless, plants show intelligent behavior: “Plants know their kin, they cooperate and fight, they mediate their relationships with one another and the other creatures that frame their lives” (p. 246). Also, “plants do speak, in chemicals. . . . the volatile chemicals they exude. They communicate with one another, and with members of other species when the situation calls for it” (p. 247). The means by which they communicate — electrical, chemical, auditory (e.g., through clicks), or kinetic (through movement) — aren’t yet understood.

Figure 17. “The wellbeing of plant communities globally now depends on human attitudes toward them. . . . A single plant is a marvel” (p. 259). (Fernleaf plant)

“Organizations of women founded the first humane societies, advocating for the rights of animals” (footnote, p. 250). These same women later went on to advocate for women’s suffrage.

Many indigenous peoples have long recognized plants as important entities deserving of respect.

Figure 18. How are these butterflies (mostly Blue Morphos) and these plants communicating and interacting for mutual benefit?

Update: This morning, August 16, 2025, I listened to the most recent edition of Living on Earth (highly recommended!), which included this interview with Zoë Schlanger, discussing her The Light Eaters : https://loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=25-P13-00033&segmentID=5

Text and photos by Shari Dorantes Hatch. Copyright © 2025. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment