- Psittaciformes

- Psittacidae

- Habitat

- Description

- Diet and Foraging

- Breeding

- Conservation Status

- Macaws

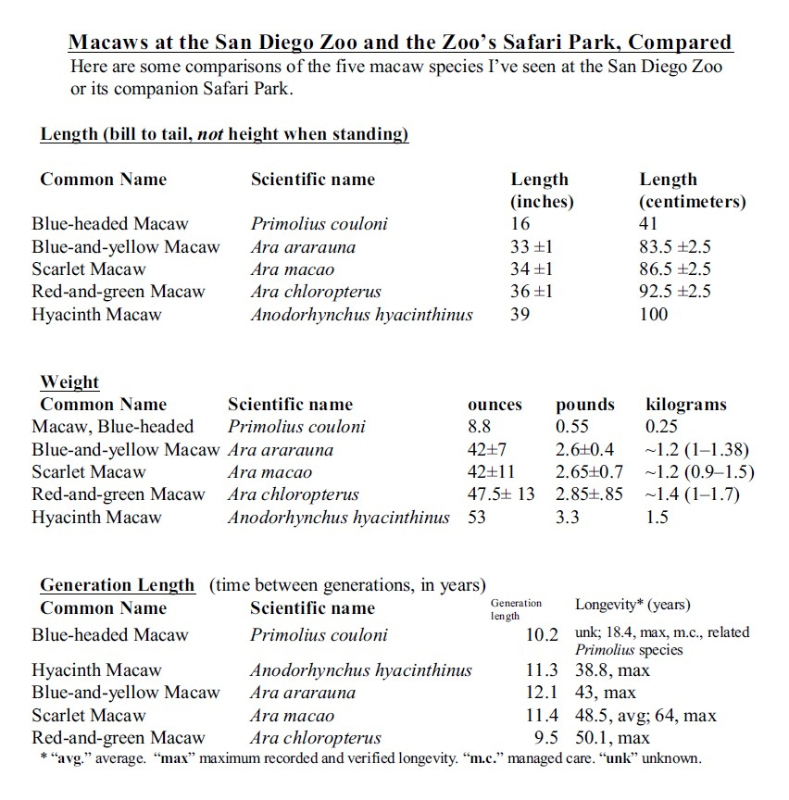

- Macaws at the San Diego Zoo and the Zoo’s Safari Park, Compared

- Blue-headed Macaw, Primolius couloni

- Distribution and Habitat

- Description

- Behavior

- Conservation Status

- Other Macaws at the San Diego Zoo or Safari Park

- Resources

Parrots are among the smartest of birds (similar to crows and other corvids); their intelligence is often compared with that of higher primates, as well as some marine mammals (e.g., dolphins and other whales).

Scientists group birds (and other animals) into a hierarchy, to more easily see which birds are more closely related to one another. Here’s the taxonomical hierarchy for macaws and other parrots.

- kingdom Animalia

- phylum Chordata

- class Aves, all living birds (~ 45 orders of birds)

- order Psittaciformes (4 families)

- family Psittacidae (37 genera, 177 species)

- order Psittaciformes (4 families)

- class Aves, all living birds (~ 45 orders of birds)

- phylum Chordata

Psittaciformes

Psittaciformes (psittacus, “parrot,” Greek) include four families of parrots:

- Psittacidae (African and New World parrots, 37 genera, 177 species),

- Psittaculidae (Old World parrots, 47 genera, 201 species),

- Cacatuidae (cockatoos, 7 genera, 22 species), and

- Strigopidae (New Zealand parrots, 2 genera, 4 species).

Some people call Psittacidae and Psittaculidae “true parrots.”

Distribution and Habitat

The 410 parrot species live mostly in tropical and subtropical areas of Australasia, the Caribbean, Central and South America, and Africa, with some temperate-zone species in New Zealand and southern South America. A few species have spread north into the southern United States and Europe. Most don’t migrate, but quite a few show nomadic movements, opportunistically seeking agreeable habitats.

Figure 01. The stunning blue Hyacinth Macaw is the largest parrot in the world.

Description

Parrots vary widely in size, from the 3″ 0.4-ounce Buff-faced Pygmy Parrot to the 39″ 53-ounce Hyacinth Macaw (the world’s longest parrot, greeter at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park). Shorter but much heavier is the 25″ Kākāpō, which weighs about 70 ounces (33–106 ounces). (You’d need a bucket of 175 pygmy parrots to balance against 1 Kākāpō.)

A parrot’s eyes are high on either side of its large head, giving it a wide visual field. In addition to having better binocular vision than most birds, it can see from just below its bill tip, to far above its head, to much of the way behind its head, without having to turn its head. Parrots can also see ultraviolet light.

Figure 02. Like other macaws, this Scarlet Macaw can easily move both its upper and its lower bill independently of its skull. The bill of a large macaw has about as much bite force as that of a large dog, yet it’s able to manipulate tiny food items deftly.

A parrot’s upper bill (“mandible”) sticks out, curves downward, and reaches a sharp point. Parrots can move the bill independently of the skull, so they can exert tremendous biting force. Large macaws have a bite force similar to that of large dogs. The lower bill is shorter, but it has a sharp, upward-pointing cutting edge, which can crunch against the inside of the upper mandible. Like other birds, its bill is made of keratin, but the inner edge of the bill tip is lined with touch receptors, facilitating deft manipulation. Seed-eating parrots have strong, sensitive tongues, enhancing their skills at maneuvering nuts and seeds in the bill, to crack them more easily.

Parrots have zygodactyl toes (two forward, two backward) with long sharp claws, making it easy to climb and to grasp branches or anything else. Most parrots are highly dextrous, easily able to manipulate food and other objects with their toes, and at least some species show a right- or left-foot preference.

Figure 03. This Blue-and-yellow Macaw uses its zygodactyl toes to stride bipedally on branches.

Though green is the most common parrot color, parrots may wear a wide array of colors. Many are vividly colored and some are brilliantly multicolored, with little or no sex differences in plumage, except in a few species (e.g., Eclectus Parrots). Sexual dimorphism may, however, appear in the ultraviolet spectrum, which we humans don’t see.

Figure 04. This vividly plumed female Eclectus Parrot (seen in the S.D. Zoo’s Owens Aviary in 2018) has a mate who is a lovely, but less captivating, green.

Locomotion

When climbing vertically, parrots show true tripedalism: A parrot can use its strong neck muscles to control its bill as a third limb, cycling among the two feet and the bill, tripedally. On the ground, they ably walk bipedally. No sweeping statements can be made about parrot flight: Some fly quite well; at least one (the Kākāpō) can’t fly at all.

Figure 05. Though not all parrot species can fly, these two macaws — Scarlet Macaw on the left, Red-and-green Macaw on the right — earn a living with their flying skills at the San Diego Zoo’s Safari Park.

Diet and Foraging

Seeds form the core of most parrots’ diet. Typically, they get the seed into their bill, crush the seed’s husk, rotate the seed in the bill, and remove the husk. As needed, they’ll use a foot to help hold a large seed in the bill while dehusking it. Dehusking not only makes the seeds easier to digest but also removes any toxins in the coat, which many seeds use as a defense against predators. Parrots eat some fruits just to get at the fruit seeds inside.

Figure 06. Unlike most other macaws, the Hyacinth Macaw specializes in eating fruits, not seeds, but this macaw nonetheless deftly uses feet, bill, and tongue to manipulate food.

Nectar-eating parrots (e.g., lories, lorikeets, hanging parrots) have brush-tipped tongues that help to collect nectar and pollen. Other parrot species also prey on invertebrates (larvae, snails, insects), and a rare few prey on vertebrates. Some species also eat clay, which absorbs toxins and releases needed minerals.

Breeding

Most parrots are monogamous, jointly finding or making nests in cavities (usually tree cavities, but sometimes cliff or ground burrows or termite mounds). The female lays and incubates the eggs (17–35 days), while the male feeds her. The hatchlings are helpless, either bare skinned or with sparse down, and parents tend to them in the nest for 3–17 weeks. Chicks may continue to get some parental care for months afterward. Many large species of parrots produce just one or very few young, sometimes yearly, sometimes less often.

Figure 07(a,b). Like other parrots, Blue-headed Macaws form monogamous pairs and enjoy having a partner with whom to share their lives and their parenting.

Intelligence

Like corvids, parrots are considered highly intelligent, with a high brain-to-body-mass ratio (comparable to higher primates). Parrots who can imitate human speech (or other sounds) have been popular pets for centuries. Some African Grey Parrots (seen in the S.D. Zoo’s Scripps Aviary) have been trained to associate spoken words with their meanings; to identify, count, and describe objects; and to utter simple sentences. In addition, some parrots show great skill at using tools and solving puzzles. Early social learning plays a key role in their adaptation, and play is important to that learning.

Conservation Status

The IUCN Red List warns that one third of all parrot species are threatened with extinction. Threats: habitat loss, hunting, pet trade, and competition from invasive species. Maybe too clever: Attempts to band or tag wild birds, to monitor them for their protection, are thwarted by parrots’ clever ability to remove the attachments.

Figure 08. Sadly, many parrot species are seriously in danger of extinction. This Blue-headed Macaw is considered “Vulnerable” to this risk.

Psittacidae

Habitat

African and New World parrots live in woodland habitats.

Description

Most psittacids have green plumage, and their body shape, head, bills, and feet are like other Psittaciformes. In the wild, they vocalize in loud squawks, but captive parrots can mimic superbly.

Diet and Foraging

New World and African parrots eat mostly fruits and seeds, supplemented by clay eating by some species in some locations.

Figure 09. Most psittacid parrots eat mostly fruits and seeds. The diet of Blue-headed Macaws hasn’t been well researched, but we can reasonably infer that they like to eat fruits, nuts (e.g., almonds), and seeds (e.g., sunflower seeds).

Breeding

New World and African parrots are monogamous, and both parents find or make a nest cavity. Females typically lay 1–11 eggs, and the male feeds her during incubation. She starts incubating the first egg as soon as she lays it, so the eggs hatch asynchronously (on different days), and incubation can take 14–28 days. After hatching, the helpless chicks are cared for by the mom for the first week, while the dad continues to feed her. After a week, both parents provide for the chicks for another 8 weeks or so.

Conservation Status

Psittacids face grave conservation threats: 24 Near Threatened (NT); 37 Vulnerable (VU); 24 Endangered (EN); and 7 Critically Endangered (CR). Keys to aiding their survival are preserving suitable habitat and preventing capture for the pet trade.

Macaws

There are 177 species of Psittacidae, only 17 of which are considered to be macaws. These 17 species are classified into 6 genera: Ara, Primolius, Anodorhynchus, Cyanopsitta, Orthopsittaca, and Diopsittaca. The macaws who live at the San Diego Zoo or Safari Park belong to the first three genera. Only one, the Blue-headed Macaw, Primolius couloni, lives in the zoo’s Parker Aviary.

Blue-headed Macaw, Primolius couloni

Figure 10. Blue-headed Macaws are smallish parrots in the Psittacidae family within the Psittaciformes order of birds. Though they may be called “mini-macaws,” they’re much bigger than most of the birds who sing to you or who gather at your feeder at home.

Distribution and Habitat

Found mostly in southwestern Amazonia, the Blue-headed Macaw inhabits the edge of humid lowland evergreen woodlands, especially those near rivers and clearings.

Description

About 16.2″ (41 cm) long, bill to tail, and almost 9 ounces (8.8 ounces; 250 g), the Blue-headed Macaw is a mid-sized bird but a small macaw (sometimes called a “mini-macaw”). Its substantial bill is about 1.4″ long (3.5 cm, forehead to tip), 1.6″ deep (4 cm, top to bottom), and 0.8″ wide (2 cm, side to side). Like other macaws, its tail is long and pointed.

Other than its turquoise head, this macaw is mostly green, with turquoise accents on its wings and dusky yellow underwing and undertail feathers. Its iris is alarmingly whitish, surrounded by a narrow maroon ring. Its legs and toes are pale pinkish, its facial skin is gray.

Figure 11(a,b). Like other macaws, Blue-headed Macaws masterfully use their toes and bill to accomplish a multitude of tasks.

Compared with other macaws, its call is softer and higher pitched. (See https://xeno-canto.org/species/Primolius-couloni)

Behavior

Little is known about this species’ diet, foraging, and breeding behavior, but it’s probably similar to that of other psittacids. In managed care, these macaws have about 2–4 white eggs per clutch, annually. Sexual maturity starts at about 1.7 years.

Figure 12. Though researchers don’t know much about the Blue-headed Macaw, we can see that these macaws pay close attention to preening their feathers.

Conservation Status

This macaw’s IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List status is VU, Vulnerable. Global population is about 9,200–46,000; population trend is declining. Threats: pet trade, hunting and trapping, human encroachment, and habitat loss. Longevity data aren’t available, but most macaws live at least 22–50 years in managed care. The closely related Yellow-collared Macaw (Primolius auricollis) has a maximum recorded age of 18.4 years. Its IUCN generation length is about 10.2 years.

Other Macaws at the San Diego Zoo

or Safari Park

At least four other species of macaw make their home at the San Diego Zoo or its companion Safari Park. Often, they’re featured animal ambassadors or participants in bird shows, as their high intelligence makes them more trainable than many other kinds of birds.

Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna)

Popular in the pet trade, this macaw’s numbers are declining in the wild. It eats a varied diet of fruits and nuts, as well as seeds, nectar, flowers, arils (seed coverings), leaves, and other parts of plants. It’s not known to migrate seasonally, but it does move opportunistically to where it can find food. They nest in tree cavities, laying 1–3 eggs per clutch, but in the wild, many of their nestlings don’t survive to fledge from the nest.

Figure 13. Unfortunately, the tremendous appeal of the Blue-and-yellow Macaw makes it attractive to the pet trade. Often, birds rescued from the pet trade are ill suited to life in the wild and must find other options after being rescued.

Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)

The largest parrot in the world, the Hyacinth Macaw’s size is only one reason it’s so widely cherished. This macaw prizes the palm fruits of just a small number of palm species, foraging for them on the ground. It does, however, occasionally snack on other fruits and occasionally on snails.

This macaw nests in tree cavities, typically laying two eggs, but often only one of the nestlings survives to fledge. (Incubation takes about a month, and post-hatch nesting lasts a while more than three months.) This macaw’s IUCN status is Vulnerable (VU).

Figure 14. Like other parrots, Hyacinth Macaws skillfully use their tongue for much more than feeding themselves.

Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus)

A relatively large and long-lived macaw, Red-and-green Macaws eat the seeds of numerous trees, the pulp and fruits of several others, and the leaves of one other. They nest not only in tree cavities, but also in cavities they find in sandstone cliffs, laying two to three eggs. Unfortunately, many of the wild nestlings are victims of predation or die of malnutrition before they’re able to fledge from the nest.

Figure 15(a,b). Red-and-green Macaws have it tough in the wild. Human settlements or even disturbances can prompt them to flee from their territory. Also, many nestlings don’t survive.

Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao)

Scarlet Macaws eat fruit, seeds, pods, leaf shoots, and flowers, as well as occasional insect snacks. These monogamous parents typically have one or two eggs per clutch, which are incubated for almost a month, then spend another four months or so being fed by their parents 4–15 times/day. Even after the young fledge, they typically stay with their parents for months afterward, perhaps until the parents start a new clutch.

Figure 16. All macaws have relatively long tails, but the Scarlet Macaw’s tail is proportionately larger than that of other macaws. In the wild, Scarlet Macaws prefer to fly in a family group, or at least with a mate.

Resources

* Please note. My pal Paul Colo — ornithologist, parrot expert, retired birdkeeper (San Diego Zoo), and great friend — helped me with identifying most of these macaws. All errors are mine, but Paul did what he could to make it more likely that I’d be accurate.

Additional information was gathered from these resources:

- Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, paid online subscription

- Psittacidae — https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/psitta3/cur/species

- Blue-headed Macaw (Primolius couloni) — Collar, N., P. F. D. Boesman, and C. J. Sharpe (2020). Blue-headed Macaw (Primolius couloni), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.buhmac1.01

- Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) — Collar, N., P. F. D. Boesman, and C. J. Sharpe (2020). Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.hyamac1.01

- Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna) — Collar, N., P. F. D. Boesman, and C. J. Sharpe (2020). Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.baymac.01

- Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus) — Collar, N., P. F. D. Boesman, and C. J. Sharpe (2020). Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.ragmac1.01

- Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao) — Collar, N., P. F. D. Boesman, and C. J. Sharpe (2020). Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.scamac1.01

- Wikipedia

- Blue-headed Macaw (Primolius couloni) — Blue-headed macaw – Wikipedia

- Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus) — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hyacinth_macaw

- Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna) — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue-and-yellow_macaw

- Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus) — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red-and-green_macaw

- Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao) — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scarlet_macaw

- Other resources

- Blue-headed Macaw (Primolius couloni)

- Hyacinth Macaw (Anodorhynchus hyacinthinus)

- Blue-and-yellow Macaw (Ara ararauna)

- Red-and-green Macaw (Ara chloropterus) —

- Scarlet Macaw (Ara macao)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100128235913/http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/macaw/

Copyright © 2025, text and photos, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

As always, I welcome your comments, suggestions, thoughts, ideas. I look forward to hearing from you.

Leave a comment