A wonderful bird is the pelican,

His bill will hold more than his belican.

He can take in his beak

Enough food for a week,

But I’m damned if I see how the helican.

“A Wonderful Bird Is the Pelican” by Dixon Lanier Merritt (1879–1972)

Bird bills can serve many wondrous purposes. Most important, birds use their bills to get food into their gullets; bills can detect, probe, catch, kill, crush, tear, pluck, deseed, peel, skin, filter, and so on. In addition, birds use their bills to dig burrows, carve holes, carry materials, build nests, gently turn eggs, feed hungry nestlings, preen feathers for flight, show off to potential mates or rivals, and much more.

Quite a few birds have ginormous bills. Even some of the tiniest birds have huge bills, relative to their body size. For instance, a tiny Costa’s Hummingbird is about 3 1/3″ (8.3 cm) long, but its bill is more than 2/3″ (1.7 cm) long, about 1/5th (20%) of the bird’s length. (The record holder is the Sword-billed Hummingbird, with a bill that’s at least half its body length.) For now, though, let’s focus on big birds with truly huge bills: pelicans and toucans.

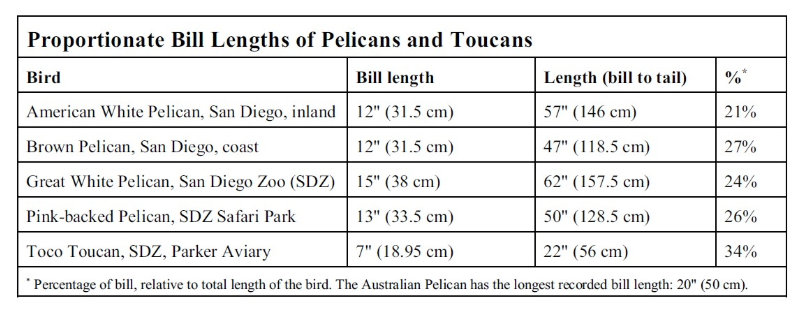

The following table can give you an idea of just how big their bills are:

It takes a lot of a bird’s resources (energy and raw materials) to develop and maintain such a big bill. Why do that? The answer differs, depending on the kind of bird and the species; sometimes, even the particular bird can find a special use for its bill.

Pelicans

On a pelican’s bill, both the upper and lower parts (its “mandibles”) are sturdy but flexible.

Unlike us mammals, pelicans (and other birds) can easily move either or both jaws up and down. The lower mandible, much wider than the upper one, suspends a huge flexible pouch beneath it. Called a “gular pouch,” it can expand widely and deeply enough to hold fat fish longer than the pelican’s bill itself. The gular pouch of our local 8-pound Brown Pelican can hold more than 10 liters of water, weighing 22 pounds. (The heaviest pelican weighs 29 pounds.)

Figure 1 (a and b). Pink-backed Pelicans, at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park: (a) fluttering gular pouches—similar to dogs’ panting—to cool off; (b) smack-talking to other pelicans.

If a pelican scoops a fish with its lower mandible, it snaps shut the upper mandible and raises the bill to the water’s surface to drain the water before swallowing the fish. Alternatively, a pelican can snag a fish with help from the downwardly hooked tip of its upper mandible. Even a squirmy fish will have trouble getting away once it’s hooked. After catching the fish, the pelican lets the water drain from its bill then tosses the fish backward into its waiting gular pouch, where it swiftly swallows the whole fish.

Figure 2 (a and b). Great White Pelicans, at the San Diego Zoo: (a) open bill; (b) draining water from its gular pouch.

American White Pelicans and several other species of pelican often work cooperatively, forming a line or a circle, to force a school of fish toward the shore or toward an opposing line of pelicans. Once they round up the fish, the pelicans’ gular pouches readily scoop up the fish. Pelicans can catch fish more effectively when they cooperate than when they fish alone. Nonetheless, some species (e.g., Pink-backed Pelicans) often fish alone, and several pelican species prefer fishing solo. For instance, our local Brown Pelicans hang out with their same-species pals, but when they’re hungry, each pelican works alone to dive for fish.

Figure 3. American Pelicans work together to scoop up fish, Santee Lakes, San Diego County, California.

You might be wondering how pelicans can preen their feathers to keep them clean and water-resistant, using those extremely long bills. That’s where their superlong, flexible necks come in handy. In addition to keeping their feathers in good shape, pelicans do stretching exercises to keep their gular pouches flexible: stretching their necks far upward while opening their bills, or laying their bills on their breasts and extending their pouches outward.

Figure 4. Brown Pelican, preening at La Jolla coast, San Diego, California.

Toucans

Toucan bills are at least as impressive as pelican bills. Perhaps the most surprising use of their bills is to radiate heat, cooling the bird from tropical heat atop sun-drenched trees. Here is a link to an infrared video showing a toucan’s bill radiating heat:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/toucans-use-enormous-bills-to-cool-off/#

In all birds, the tissue surrounding the jaw contains blood and nerve cells, covered by an outer rhamphotheca. The tough rhamphotheca is made mostly of keratin, the same sturdy substance as your fingernails. Like your fingernails, the rhamphotheca keeps growing throughout the bird’s life, allowing for wear and tear. The toucan’s nostrils fit neatly into a space between its upper bill and its head.

Figure 5. Toco Toucan eating fruit in the San Diego Zoo’s Parker Aviary.

Toucans can use their bills to make nonvocal sounds, such as by clattering their mandibles or hitting their bills against a branch. Toucan bills also serve some social functions, but their main purpose is to grab and eat food. The long bill can nab fruit on branches too slender to hold the bird’s weight. To eat with those humongous honkers, toucans grasp fruits with the tips of their bills, then toss the food backward into the throat. For soft fruits, that strategy works well.

Figure 6. Toco Toucan eating fruit, tossing back each bite.

To cope with hard seeds, though, the toucan expertly manipulates its powerful mandibles to crush the seeds to make them edible. Their bills can also deftly remove hard husks before feasting on the juicy fruit inside. For fruits with stony pits, the toucan swallows the whole fruits then later regurgitates just the pits. (When nesting, they use the regurgitated pits to line their nests.)

In addition, Toco Toucans spice up their fruity diet with insects, spiders, reptiles, amphibians, eggs, and even small birds or mammals. If a critter is too big to be swallowed whole, the toucan holds it firmly with its toes and tears off chunks to toss back into its gullet. Though strong and tough, the toucan bill is actually lightweight because it’s mostly hollow. The toucan’s flat tongue is almost as long as the bill itself.

Figure 7. Even as chicks, Toco Toucans can wield their huge bills to delicately preen their feathers.

Copyright 2025, text and photos, Shari Dorantes Hatch. All rights reserved.

Resources

Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Online (paid) Subscription

- Costa’s Hummingbird, Calypte costae; William H. Baltosser and Peter E. Scott; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated January 1, 1996

- American White Pelican, Pelecanus erythrorhynchos; Fritz L. Knopf and Roger M. Evans; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated November 1, 2004

- Brown Pelican, Pelecanus occidentalis; Mark Shields; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated July 15, 2014

- Great White Pelican, Pelecanus onocrotalus; Andrew Elliott, David Christie, Francesc Jutglar, Ernest Garcia, and Guy M. Kirwan; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated April 26, 2015

- Pink-backed Pelican, Pelecanus rufescens; Andrew Elliott, David Christie, Francesc Jutglar, Ernest Garcia, and Guy M. Kirwan; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated February 21, 2015

- Toco Toucan, Ramphastos toco; Carolyn W. Sedgwick; Version: 1.0 — Published March 4, 2020; Text last updated August 6, 2010

Books and Textbooks

- Bird Families of the World: An Invitation to the Spectacular Diversity of Birds. David W. Winkler, Shawn M. Billerman, Irby J. Lovette (2015). Lynx, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, pp. 189, 240–241.

- Handbook of Bird Biology, edited by Irby Lovette & John Fitzpatrick (2016). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, pp. 172–174, 221, 283–284, 300.

- Ornithology: Foundation, Analysis, and Application, edited by Michael Morrison, Amanda Rodewald, Gary Voelker, Melanie Colón, Jonathan Prather (2018). Johns Hopkins Press, pp. 133–134.

- The World of Birds, Jonathan Elphick (2014). Firefly Books, pp. 21–24, 26, 108, 121, 320–321, 435–437.

* I am eternally grateful for the help of Mia McPherson, who guided me to drastically improve this particular post. Her guidance will doubtlessly enormously improve all of the posts that follow. I can’t emphasize enough how much I appreciate her supportive encouragement and specific technical information, which she conveyed in easy-to-understand terms, making it so easy to follow her suggestions for improvement. Thank you, Mia. I deeply appreciate your help.

Leave a comment